This is an old revision of this page, as edited by AnonQuixote (talk | contribs) at 00:10, 4 January 2021 (→In non-human animals: Added paragraph on dogs). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 00:10, 4 January 2021 by AnonQuixote (talk | contribs) (→In non-human animals: Added paragraph on dogs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Eyes not aligning when looking at something For the protein Strabismus, see Strabismus (protein).Medical condition

| Strabismus | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Heterotropia, crossed eyes, squint |

| |

| A person with exotropia, an outward deviated eye | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

| Symptoms | Nonaligned eyes |

| Complications | Amblyopia, double vision |

| Types | Esotropia (eyes crossed); exotropia (eyes diverge); hypertropia (eyes vertically misaligned) |

| Causes | Muscle dysfunction, farsightedness, problems in the brain, trauma, infections |

| Risk factors | Premature birth, cerebral palsy, family history |

| Diagnostic method | Observing light reflected from the pupil |

| Differential diagnosis | Cranial nerve disease |

| Treatment | Glasses, surgery |

| Frequency | ~2% (children) |

Strabismus is a condition in which the eyes do not properly align with each other when looking at an object. The eye that is focused on an object can alternate. The condition may be present occasionally or constantly. If present during a large part of childhood, it may result in amblyopia or loss of depth perception. If onset is during adulthood, it is more likely to result in double vision.

Strabismus can occur due to muscle dysfunction, farsightedness, problems in the brain, trauma or infections. Risk factors include premature birth, cerebral palsy and a family history of the condition. Types include esotropia, where the eyes are crossed ("cross eyed"); exotropia, where the eyes diverge ("lazy eyed" or "wall eyed"); and hypertropia where they are vertically misaligned. They can also be classified by whether the problem is present in all directions a person looks (comitant) or varies by direction (incomitant). Diagnosis may be made by observing the light reflecting from the person's eyes and finding that it is not centered on the pupil. Another condition that produces similar symptoms is a cranial nerve disease.

Treatment depends on the type of strabismus and the underlying cause. This may include the use of glasses and possibly surgery. Some types benefit from early surgery. Strabismus occurs in about 2% of children. The term is from the Greek strabismós, meaning "to squint". Other terms for the condition include "squint" and "cast of the eye". "Wall-eye" has been used when the eyes turn away from each other.

Signs and symptoms

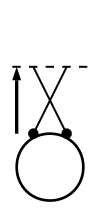

Aligned vergence

Aligned vergence Esotropia

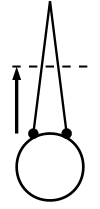

Esotropia Exotropia

Exotropia

When observing a person with strabismus, the misalignment of the eyes may be quite apparent. A person with a constant eye turn of significant magnitude is very easy to notice. However, a small magnitude or intermittent strabismus can easily be missed upon casual observation. In any case, an eye care professional can conduct various tests, such as cover testing, to determine the full extent of the strabismus.

Symptoms of strabismus include double vision and eye strain. To avoid double vision, the brain may adapt by ignoring one eye. In this case, often no noticeable symptoms are seen other than a minor loss of depth perception. This deficit may not be noticeable in someone who has had strabismus since birth or early childhood, as they have likely learned to judge depth and distances using monocular cues. However, a constant unilateral strabismus causing constant suppression is a risk for amblyopia in children. Small-angle and intermittent strabismus are more likely to cause disruptive visual symptoms. In addition to headaches and eye strain, symptoms may include an inability to read comfortably, fatigue when reading, and unstable or "jittery" vision.

Psychosocial effects

See also: Prevalence and impact of reduced stereopsis in humans

People of all ages who have noticeable strabismus may experience psychosocial difficulties. Attention has also been drawn to potential socioeconomic impact resulting from cases of detectable strabismus. A socioeconomic consideration exists as well in the context of decisions regarding strabismus treatment, including efforts to re-establish binocular vision and the possibility of stereopsis recovery.

One study has shown that strabismic children commonly exhibit behaviors marked by higher degrees of inhibition, anxiety, and emotional distress, often leading to outright emotional disorders. These disorders are often related to a negative perception of the child by peers. This is due not only to an altered aesthetic appearance, but also because of the inherent symbolic nature of the eye and gaze, and the vitally important role they play in an individual's life as social components. For some, these issues improved dramatically following strabismus surgery. Notably, strabismus interferes with normal eye contact, often causing embarrassment, anger, and feelings of awkwardness, thereby affecting social communication in a fundamental way, with a possible negative effect on self esteem.

Children with strabismus, particularly those with exotropia—an outward turn—may be more likely to develop a mental health disorder than normal-sighted children. Researchers have theorized that esotropia (an inward turn) was not found to be linked to a higher propensity for mental illness due to the age range of the participants, as well as the shorter follow-up time period; esotropic children were monitored to a mean age of 15.8 years, compared with 20.3 years for the exotropic group.

A subsequent study with participants from the same area monitored people with congenital esotropia for a longer time period; results indicated that people who are esotropic were also more likely to develop mental illness of some sort upon reaching early adulthood, similar to those with constant exotropia, intermittent exotropia, or convergence insufficiency. The likelihood was 2.6 times that of controls. No apparent association with premature birth was observed, and no evidence was found linking later onset of mental illness to psychosocial stressors frequently encountered by those with strabismus.

Investigations have highlighted the impact that strabismus may typically have on quality of life. Studies in which subjects were shown images of strabismic and non-strabismic persons showed a strong negative bias towards those visibly displaying the condition, clearly demonstrating the potential for future socioeconomic implications with regard to employability, as well as other psychosocial effects related to an individual's overall happiness.

Adult and child observers perceived a right heterotropia as more disturbing than a left heterotropia, and child observers perceived an esotropia as "worse" than an exotropia. Successful surgical correction of strabismus—for adult as well as children—has been shown to have a significantly positive effect on psychological well-being.

Very little research exists regarding coping strategies employed by adult strabismics. One study categorized coping methods into three subcategories: avoidance (refraining from participation in an activity), distraction (deflecting attention from the condition), and adjustment (approaching an activity differently). The authors of the study suggested that individuals with strabismus may benefit from psychosocial support such as interpersonal skills training. No studies have evaluated whether psychosocial interventions have had any benefits on individuals undergoing strabismus surgery.

Pathophysiology

The extraocular muscles control the position of the eyes. Thus, a problem with the muscles or the nerves controlling them can cause paralytic strabismus. The extraocular muscles are controlled by cranial nerves III, IV, and VI. An impairment of cranial nerve III causes the associated eye to deviate down and out and may or may not affect the size of the pupil. Impairment of cranial nerve IV, which can be congenital, causes the eye to drift up and perhaps slightly inward. Sixth nerve palsy causes the eyes to deviate inward and has many causes due to the relatively long path of the nerve. Increased cranial pressure can compress the nerve as it runs between the clivus and brain stem. Also, if the doctor is not careful, twisting of the baby's neck during forceps delivery can damage cranial nerve VI.

Evidence indicates a cause for strabismus may lie with the input provided to the visual cortex. This allows for strabismus to occur without the direct impairment of any cranial nerves or extraocular muscles.

Strabismus may cause amblyopia due to the brain ignoring one eye. Amblyopia is the failure of one or both eyes to achieve normal visual acuity despite normal structural health. During the first seven to eight years of life, the brain learns how to interpret the signals that come from an eye through a process called visual development. Development may be interrupted by strabismus if the child always fixates with one eye and rarely or never fixates with the other. To avoid double vision, the signal from the deviated eye is suppressed, and the constant suppression of one eye causes a failure of the visual development in that eye.

Also, amblyopia may cause strabismus. If a great difference in clarity occurs between the images from the right and left eyes, input may be insufficient to correctly reposition the eyes. Other causes of a visual difference between right and left eyes, such as asymmetrical cataracts, refractive error, or other eye disease, can also cause or worsen strabismus.

Accommodative esotropia is a form of strabismus caused by refractive error in one or both eyes. Due to the near triad, when a person engages accommodation to focus on a near object, an increase in the signal sent by cranial nerve III to the medial rectus muscles results, drawing the eyes inward; this is called the accommodation reflex. If the accommodation needed is more than the usual amount, such as with people with significant hyperopia, the extra convergence can cause the eyes to cross.

Diagnosis

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

During an eye examination, a test such as cover testing or the Hirschberg test is used in the diagnosis and measurement of strabismus and its impact on vision. Retinal birefringence scanning can be used for screening of young children for eye misaligments. A Cochrane review to examine different types of diagnosis test found only one study. This study used a photoscreener which was found to have high specificity (accurate in identifying those without the condition) but low sensitivity (inaccurate in identifying those with the condition).

Several classifications are made when diagnosing strabismus.

Latency

Strabismus can be manifest (-tropia) or latent (-phoria). A manifest deviation, or heterotropia (which may be eso-, exo-, hyper-, hypo-, cyclotropia or a combination of these), is present while the person views a target binocularly, with no occlusion of either eye. The person is unable to align the gaze of each eye to achieve fusion. A latent deviation, or heterophoria (eso-, exo-, hyper-, hypo-, cyclophoria or a combination of these), is only present after binocular vision has been interrupted, typically by covering one eye. This type of person can typically maintain fusion despite the misalignment that occurs when the positioning system is relaxed. Intermittent strabismus is a combination of both of these types, where the person can achieve fusion, but occasionally or frequently falters to the point of a manifest deviation.

Onset

Strabismus may also be classified based on time of onset, either congenital, acquired, or secondary to another pathological process. Many infants are born with their eyes slightly misaligned, and this is typically outgrown by six to 12 months of age. Acquired and secondary strabismus develop later. The onset of accommodative esotropia, an overconvergence of the eyes due to the effort of accommodation, is mostly in early childhood. Acquired non-accommodative strabismus and secondary strabismus are developed after normal binocular vision has developed. In adults with previously normal alignment, the onset of strabismus usually results in double vision.

Any disease that causes vision loss may also cause strabismus, but it can also result from any severe and/or traumatic injury to the affected eye. Sensory strabismus is strabismus due to vision loss or impairment, leading to horizontal, vertical or torsional misalignment or to a combination thereof, with the eye with poorer vision drifting slightly over time. Most often, the outcome is horizontal misalignment. Its direction depends on the person's age at which the damage occurs: people whose vision is lost or impaired at birth are more likely to develop esotropia, whereas people with acquired vision loss or impairment mostly develop exotropia. In the extreme, complete blindness in one eye generally leads to the blind eye reverting to an anatomical position of rest.

Although many possible causes of strabismus are known, among them severe and/or traumatic injuries to the afflicted eye, in many cases no specific cause can be identified. This last is typically the case when strabismus is present since early childhood.

Results of a U.S. cohort study indicate that the incidence of adult-onset strabismus increases with age, especially after the sixth decade of life, and peaks in the eighth decade of life, and that the lifetime risk of being diagnosed with adult-onset strabismus is approximately 4%.

Laterality

Strabismus may be classified as unilateral if the one eye consistently deviates, or alternating if either of the eyes can be seen to deviate. Alternation of the strabismus may occur spontaneously, with or without subjective awareness of the alternation. Alternation may also be triggered by various tests during an eye exam. Unilateral strabismus has been observed to result from a severe or traumatic injury to the affected eye.

Direction and latency

Horizontal deviations are classified into two varieties, using prefixes: eso- describes inward or convergent deviations towards the midline, while exo- describes outward or divergent misalignment. Vertical deviations are also classified into two varieties, using prefixes: hyper- is the term for an eye whose gaze is directed higher than the fellow eye, while hypo- refers to an eye whose gaze is directed lower. Finally, the prefix cyclo- refers to torsional strabismus, which occurs when the eyes rotate around the anterior-posterior axis to become misaligned and is quite rare.

These five directional prefixes are combined with -tropia (if manifest) or -phoria (if latent) to describe various types of strabismus. For example, a constant left hypertropia exists when a person's left eye is always aimed higher than the right. A person with an intermittent right esotropia has a right eye that occasionally drifts toward the person's nose, but at other times is able to align with the gaze of the left eye. A person with a mild exophoria can maintain fusion during normal circumstances, but when the system is disrupted, the relaxed posture of the eyes is slightly divergent.

Other considerations

Strabismus can be further classified as follows:

- Paretic strabismus is due to paralysis of one or several extraocular muscles.

- Nonparetic strabismus is not due to paralysis of extraocular muscles.

- Comitant (or concomitant) strabismus is a deviation that is the same magnitude regardless of gaze position.

- Noncomitant (or incomitant) strabismus has a magnitude that varies as the person shifts his or her gaze up, down, or to the sides.

Nonparetic strabismus is generally concomitant. Most types of infant and childhood strabismus are comitant. Paretic strabismus can be either comitant or noncomitant. Incomitant strabismus is almost always caused by a limitation of ocular rotations that is due to a restriction of extraocular eye movement (ocular restriction) or due to extraocular muscle paresis. Incomitant strabismus cannot be fully corrected by prism glasses, because the eyes would require different degrees of prismatic correction dependent on the direction of the gaze. Incomitant strabismus of the eso- or exo-type are classified as "alphabet patterns": they are denoted as A- or V- or more rarely λ-, Y- or X-pattern depending on the extent of convergence or divergence when the gaze moves upward or downward. These letters of the alphabet denote ocular motility pattern that have a similarity to the respective letter: in the A-pattern there is (relatively speaking) more convergence when the gaze is directed upwards and more divergence when it is directed downwards, in the V-pattern it is the contrary, in the λ-, Y- and X-patterns there is little or no strabismus in the middle position but relatively more divergence in one or both of the upward and downward positions, depending on the "shape" of the letter.

Types of incomitant strabismus include: Duane syndrome, horizontal gaze palsy, and congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles.

When the misalignment of the eyes is large and obvious, the strabismus is called large-angle, referring to the angle of deviation between the lines of sight of the eyes. Less severe eye turns are called small-angle strabismus. The degree of strabismus can vary based on whether the person is viewing a distant or near target.

Strabismus that sets in after eye alignment had been surgically corrected is called consecutive strabismus.

Differential diagnosis

Pseudostrabismus is the false appearance of strabismus. It generally occurs in infants and toddlers whose bridge of the nose is wide and flat, causing the appearance of esotropia due to less sclera being visible nasally. With age, the bridge of the child's nose narrows and the folds in the corner of the eyes become less prominent.

Retinoblastoma may also result in abnormal light reflection from the eye.

Management

Main article: Management of strabismusStrabismus is usually treated with a combination of eyeglasses, vision therapy, and surgery, depending on the underlying reason for the misalignment. As with other binocular vision disorders, the primary goal is comfortable, single, clear, normal binocular vision at all distances and directions of gaze.

Whereas amblyopia (lazy eye), if minor and detected early, can often be corrected with use of an eye patch on the dominant eye or vision therapy, the use of eye patches is unlikely to change the angle of strabismus.

Glasses

In cases of accommodative esotropia, the eyes turn inward due to the effort of focusing far-sighted eyes, and the treatment of this type of strabismus necessarily involves refractive correction, which is usually done via corrective glasses or contact lenses, and in these cases surgical alignment is considered only if such correction does not resolve the eye turn.

In case of strong anisometropia, contact lenses may be preferable to spectacles because they avoid the problem of visual disparities due to size differences (aniseikonia) which is otherwise caused by spectacles in which the refractive power is very different for the two eyes. In a few cases of strabismic children with anisometropic amblyopia, a balancing of the refractive error eyes via refractive surgery has been performed before strabismus surgery was undertaken.

Early treatment of strabismus when the person is a baby may reduce the chance of developing amblyopia and depth perception problems. However, a review of randomized controlled trials concluded that the use of corrective glasses to prevent strabismus is not supported by existing research. Most children eventually recover from amblyopia if they have had the benefit of patches and corrective glasses. Amblyopia has long been considered to remain permanent if not treated within a critical period, namely before the age of about seven years; however, recent discoveries give reason to challenge this view and to adapt the earlier notion of a critical period to account for stereopsis recovery in adults.

Eyes that remain misaligned can still develop visual problems. Although not a cure for strabismus, prism lenses can also be used to provide some temporary comfort and to prevent double vision from occurring.

Glasses affect the position by changing the person's reaction to focusing. Prisms change the way light, and therefore images, strike the eye, simulating a change in the eye position.

Surgery

Strabismus surgery does not remove the need for a child to wear glasses. Currently it is unknown whether there are any differences for completing strabismus surgery before or after amblyopia therapy in children.

Strabismus surgery attempts to align the eyes by shortening, lengthening, or changing the position of one or more of the extraocular eye muscles. The procedure can typically be performed in about an hour, and requires about six to eight weeks for recovery. Adjustable sutures may be used to permit refinement of the eye alignment in the early postoperative period. It is unclear if there are differences between adjustable versus non-adjustable sutures as it has not been sufficiently studied. An alternative to the classical procedure is minimally invasive strabismus surgery (MISS) that uses smaller incisions than usual.

Medication

Medication is used for strabismus in certain circumstances. In 1989, the US FDA approved botulinum toxin therapy for strabismus in people over 12 years old. Most commonly used in adults, the technique is also used for treating children, in particular children affected by infantile esotropia. The toxin is injected in the stronger muscle, causing temporary and partial paralysis. The treatment may need to be repeated three to four months later once the paralysis wears off. Common side effects are double vision, droopy eyelid, overcorrection, and no effect. The side effects typically resolve also within three to four months. Botulinum toxin therapy has been reported to be similarly successful as strabismus surgery for people with binocular vision and less successful than surgery for those who have no binocular vision.

Prognosis

When strabismus is congenital or develops in infancy, it can cause amblyopia, in which the brain ignores input from the deviated eye. Even with therapy for amblyopia, stereoblindness may occur. The appearance of strabismus may also be a cosmetic problem. One study reported 85% of adult with strabismus "reported that they had problems with work, school, and sports because of their strabismus." The same study also reported 70% said strabismus "had a negative effect on their self-image." A second operation is sometimes required to straighten the eyes.

In non-human animals

Siamese cats and related breeds are prone to having crossed eyes. Research suggests this is a behavioral compensation for developmental abnormalities in the routing of nerves in the optic chiasm.

Strabismus may also occur in dogs, most often due to imbalanced muscle tone of the muscles surrounding the eye. Some breeds such as the Shar Pei are genetically predisposed to the condition. Treatment may involve surgery or therapy to strengthen the muscles.

References

- ^ "Strabismus noun - Definition, pictures, pronunciation and usage notes | Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary". www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ "Visual Processing: Strabismus". National Eye Institute. National Institutes of Health. June 16, 2010. Archived from the original on October 5, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- ^ Gunton KB, Wasserman BN, DeBenedictis C (September 2015). "Strabismus". Primary Care. 42 (3): 393–407. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2015.05.006. PMID 26319345.

- "strabismus (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper. Archived from the original on December 12, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- Brown, Lesley (1993). The New shorter Oxford English dictionary on historical principles. Oxford: Clarendon. pp. Strabismus. ISBN 978-0-19-861271-1.

- "strabismus". English: Oxford Living Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. 2016. Archived from the original on April 21, 2016. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- "the definition of squint". Dictionary.com. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- "wall eye". English: Oxford Living Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on November 5, 2017. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ Satterfield D, Keltner JL, Morrison TL (August 1993). "Psychosocial aspects of strabismus study". Archives of Ophthalmology. 111 (8): 1100–5. doi:10.1001/archopht.1993.01090080096024. PMID 8166786.

- ^ Olitsky SE, Sudesh S, Graziano A, Hamblen J, Brooks SE, Shaha SH (August 1999). "The negative psychosocial impact of strabismus in adults". Journal of AAPOS. 3 (4): 209–11. doi:10.1016/S1091-8531(99)70004-2. PMID 10477222.

- ^ Uretmen O, Egrilmez S, Kose S, Pamukçu K, Akkin C, Palamar M (April 2003). "Negative social bias against children with strabismus". Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 81 (2): 138–42. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0420.2003.00024.x. PMID 12752051.

- See peer discussion in: Mets MB, Beauchamp C, Haldi BA (2003). "Binocularity following surgical correction of strabismus in adults". Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 101: 201–5, discussion 205–7. doi:10.1016/s1091853104001375 (inactive September 1, 2020). PMC 1358989. PMID 14971578.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of September 2020 (link) - Bernfeld A (1982). "" [Psychological repercussions of strabismus in children]. Journal Français d'Ophtalmologie (in French). 5 (8–9): 523–30. PMID 7142664.

- "Strabismus". All About Vision. Access Media Group. Archived from the original on September 16, 2014.

- Tonge BJ, Lipton GL, Crawford G (March 1984). "Psychological and educational correlates of strabismus in school children". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 18 (1): 71–7. doi:10.3109/00048678409161038. PMID 6590030. S2CID 42734067.

- Mohney BG, McKenzie JA, Capo JA, Nusz KJ, Mrazek D, Diehl NN (November 2008). "Mental illness in young adults who had strabismus as children". Pediatrics. 122 (5): 1033–8. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-3484. PMC 2762944. PMID 18977984.

- Beauchamp GR, Felius J, Stager DR, Beauchamp CL (December 2005). "The utility of strabismus in adults". Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 103: 164–71, discussion 171–2. PMC 1447571. PMID 17057800.

- Mojon-Azzi SM, Mojon DS (November 2009). "Strabismus and employment: the opinion of headhunters". Acta Ophthalmologica. 87 (7): 784–8. doi:10.1111/j.1755-3768.2008.01352.x. PMID 18976309.

- Mojon-Azzi SM, Mojon DS (October 2007). "Opinion of headhunters about the ability of strabismic subjects to obtain employment". Ophthalmologica. Journal International d'Ophtalmologie. International Journal of Ophthalmology. Zeitschrift für Augenheilkunde. 221 (6): 430–3. doi:10.1159/000107506. PMID 17947833. S2CID 29398388.

- Mojon-Azzi SM, Kunz A, Mojon DS (May 2011). "The perception of strabismus by children and adults" (PDF). Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv für Klinische und Experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 249 (5): 753–7. doi:10.1007/s00417-010-1555-y. PMID 21063886. S2CID 10989351.

- Burke JP, Leach CM, Davis H (May 1997). "Psychosocial implications of strabismus surgery in adults". Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 34 (3): 159–64. PMID 9168420.

- Durnian JM, Noonan CP, Marsh IB (April 2011). "The psychosocial effects of adult strabismus: a review" (PDF). The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 95 (4): 450–3. doi:10.1136/bjo.2010.188425. PMID 20852320. S2CID 206870079.

- Jackson S, Gleeson K (August 2013). "Living and coping with strabismus as an adult". European Medical Journal Ophthalmology. 1: 15–22. Archived from the original on June 21, 2017.

- MacKenzie K, Hancox J, McBain H, Ezra DG, Adams G, Newman S (May 2016). "Psychosocial interventions for improving quality of life outcomes in adults undergoing strabismus surgery" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (5): CD010092. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010092.pub4. PMID 27171652.

- ^ Cunningham ET, Riordan-Eva P (May 17, 2011). Vaughan & Asbury's general ophthalmology (18th ed.). McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-163420-5.

- Tychsen L (August 2012). "The cause of infantile strabismus lies upstairs in the cerebral cortex, not downstairs in the brainstem". Archives of Ophthalmology. 130 (8): 1060–1. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.1481. PMID 22893080.

- Hull, Sarah; Tailor, Vijay; Balduzzi, Sara; Rahi, Jugnoo; Schmucker, Christine; Virgili, Gianni; Dahlmann-Noor, Annegret (November 6, 2017). "Tests for detecting strabismus in children aged 1 to 6 years in the community". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: CD011221. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011221.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 6486041. PMID 29105728.

- ^ Nield LS, Mangano LM (April 2009). "Strabismus: What to Tell Parents and When to Consider Surgery". Consultant. 49 (4). Archived from the original on April 14, 2009.

- ^ "Strabismus". MedlinePlus Encyclopedia. US National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on March 27, 2013. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ^ Rosenbaum AL, Santiago AP (1999). Clinical Strabismus Management: Principles and Surgical Techniques. David Hunter. pp. 193–194. ISBN 978-0-7216-7673-9. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved June 21, 2016 – via Google Books.

- Havertape SA, Cruz OA, Chu FC (November 2001). "Sensory strabismus--eso or exo?". Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 38 (6): 327–30, quiz 354–5. PMID 11759769.

- Havertape SA, Cruz OA (January 2001). "Sensory Strabismus: When Does it Happen and Which Way Do They Turn?". American Orthoptic Journal. 51 (1): 36–38. doi:10.3368/aoj.51.1.36. S2CID 71251248.

- Albert DM, Perkins ES, Gamm DM (March 24, 2017). "Eye disease". Encyclopædia Britannica. Strabismus (squint). Archived from the original on March 16, 2017.

- Rubin ML, Winograd LA (2003). "Crossed Eyes (Strabismus): Did you really understand what your eye doctor told you?". Taking Care of Your Eyes: A Collection of the Patient Education Handouts Used by America's Leading Eye Doctors. Triad Communications. ISBN 978-0-937404-61-4.

- Martinez-Thompson JM, Diehl NN, Holmes JM, Mohney BG (April 2014). "Incidence, types, and lifetime risk of adult-onset strabismus". Ophthalmology. 121 (4): 877–82. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.10.030. PMC 4321874. PMID 24321142.

- Friedman NJ, Kaiser PK, Pineda R (2009). The Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary illustrated manual of ophthalmology (3rd ed.). Saunders/Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4377-0908-7.

- "concomitant strabimus". TheFreeDictionary. Farlex.

- ^ Wright KW, Spiegel PH (January 2003). Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-387-95478-3. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016 – via Google Books.

- "Adult Strabismus Surgery – 2013". ONE Network. American Association of Ophthalmology. April 2013. Archived from the original on September 7, 2014. Retrieved September 6, 2014.

- Plotnik JL, Bartiss MJ (October 13, 2015). "A-Pattern Esotropia and Exotropia". Medscape. Archived from the original on September 8, 2014. Retrieved September 8, 2014.

- Engle EC (February 2007). "Genetic basis of congenital strabismus". Archives of Ophthalmology. 125 (2): 189–95. doi:10.1001/archopht.125.2.189. PMID 17296894.

- Eskridge JB (October 1993). "Persistent diplopia associated with strabismus surgery". Optometry and Vision Science. 70 (10): 849–53. doi:10.1097/00006324-199310000-00013. PMID 8247489.

- Astle WF, Rahmat J, Ingram AD, Huang PT (December 2007). "Laser-assisted subepithelial keratectomy for anisometropic amblyopia in children: outcomes at 1 year". Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery. 33 (12): 2028–34. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.07.024. PMID 18053899. S2CID 1886316.

- Jones-Jordan, Lisa; Wang, Xue; Scherer, Roberta W.; Mutti, Donald O. (April 2, 2020). "Spectacle correction versus no spectacles for prevention of strabismus in hyperopic children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD007738. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007738.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7117860. PMID 32240551.

- Korah S, Philip S, Jasper S, Antonio-Santos A, Braganza A (October 2014). "Strabismus surgery before versus after completion of amblyopia therapy in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10 (10): CD009272. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009272.pub2. PMC 4438561. PMID 25315969.

- Parikh RK, Leffler CT (July 2013). "Loop suture technique for optional adjustment in strabismus surgery". Middle East African Journal of Ophthalmology. 20 (3): 225–8. doi:10.4103/0974-9233.114797. PMC 3757632. PMID 24014986.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Hassan S, Haridas A, Sundaram V (March 2018). Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group (ed.). "Adjustable versus non-adjustable sutures for strabismus". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3: CD004240. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004240.pub4. PMC 6494216. PMID 29527670.

- "Re: Docket No. FDA-2008-P-0061" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. United States Department of Health and Human Services. April 30, 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- Kowal L, Wong E, Yahalom C (December 2007). "Botulinum toxin in the treatment of strabismus. A review of its use and effects". Disability and Rehabilitation. 29 (23): 1823–31. doi:10.1080/09638280701568189. PMID 18033607. S2CID 19053824.

- Thouvenin D, Lesage-Beaudon C, Arné JL (January 2008). "[Botulinum injection in infantile strabismus. Results and incidence on secondary surgery in a long-term survey of 74 cases treated before 36 months of age]" [Botulinum injection in infantile strabismus. Results and incidence on secondary surgery in a long-term survey of 74 cases treated before 36 months of age]. Journal Français d'Ophtalmologie (in French). 31 (1): 42–50. doi:10.1016/S0181-5512(08)70329-2. PMID 18401298. Archived from the original on November 5, 2017.

- de Alba Campomanes AG, Binenbaum G, Campomanes Eguiarte G (April 2010). "Comparison of botulinum toxin with surgery as primary treatment for infantile esotropia". Journal of AAPOS. 14 (2): 111–6. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2009.12.162. PMID 20451851.

- Gursoy H, Basmak H, Sahin A, Yildirim N, Aydin Y, Colak E (June 2012). "Long-term follow-up of bilateral botulinum toxin injections versus bilateral recessions of the medial rectus muscles for treatment of infantile esotropia". Journal of AAPOS. 16 (3): 269–73. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2012.01.010. PMID 22681945.

- Rowe, Fiona J.; Noonan, Carmel P. (February 15, 2012). Rowe, Fiona J (ed.). "Botulinum toxin for the treatment of strabismus". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD006499. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006499.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 22336817.

- "Treatment for "lazy eye" is more than cosmetic". Scribe/Alum Notes. Wayne State University. Spring 2001. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015.

- Blake, Randolph; Crawford, M.L.J. (1974). "Development of strabismus in Siamese cats". Brain Research. 77 (3): 492–496. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(74)90637-4. ISSN 0006-8993.

- "Diseases of the orbit of the eye in dogs". PetMD. September 23, 2008. Retrieved January 3, 2021.

Further reading

- Donahue SP, Buckley EG, Christiansen SP, Cruz OA, Dagi LR (August 2014). "Difficult problems: strabismus". Journal of American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus (JAAPOS). 18 (4): e41. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2014.07.132.

External links

| Classification | D |

|---|---|

| External resources |