This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Apaugasma (talk | contribs) at 20:46, 8 January 2021. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:46, 8 January 2021 by Apaugasma (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) | This is the user sandbox of Apaugasma. A user sandbox is a subpage of the user's user page. It serves as a testing spot and page development space for the user and is not an encyclopedia article. Create or edit your own sandbox here. Other sandboxes: Main sandbox | Template sandbox Finished writing a draft article? Are you ready to request review of it by an experienced editor for possible inclusion in Misplaced Pages? Submit your draft for review! |

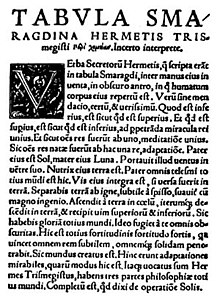

"As above, so below" is a popular modern paraphrase of the first part of the second verse of the Emerald Tablet (a compact and cryptic Hermetic text first attested in the late eight or early ninth century), as it appears in its most widely divulged medieval Latin translation:

Quod est superius est sicut quod inferius, et quod inferius est sicut quod est superius.

That which is above is like to that which is below, and that which is below is like to that which is above.

Interpretations

In this formulation, the verse is often understood as a reference to the effects of celestial mechanics upon terrestrial events. This would include the effects of the Sun upon the change of seasons, or those of the Moon upon the tides, but also more elaborate astrological effects.

According to another common interpretation, which also takes the second part of the original Latin verse into consideration, it refers to the structural similarities between the macrocosm (from Greek makros kosmos, "the great world": the universe as a whole, understood as a great living being) and the microcosm (from Greek mikros kosmos, "the small world": the human being, understood as a miniature universe).

Difference from the original Arabic

It may be noted that the original Arabic of the verse in the Emerald Tablet itself does not mention the similarity between what is above and what is below, but rather their reciprocal origin "from" each other:

Arabic: إن الأعلى من الأسفل والأسفل من الأعلى

Latin translation by Hugo of Santalla: Superiora de inferioribus, inferiora de superioribus

English translation of the Arabic: That which is above is from that which is below, and that which is below is from that which is above.

In popular culture

The phrase is very popular in modern occultist and esotericist circles. It has also been adopted as a title for various works of art:

- As Above, So Below (film), a 2014 found-footage horror film

- As Above, So Below (Forced Entry album), 1991

- As Above, So Below (Angel Witch album), 2012

- As Above So Below (Azure Ray EP), 2012

- As Above, So Below (Stonefield album), 2016

- As Above, So Below, a 1998 studio album by Barry Adamson

- As Above So Below, a 2011 studio album by singer Anthony David

- As Above So Below, a 2020 studio album by rapper Vinnie Paz

- As Above So Below, a 2020 song from DJs Phoenix Lord & Saggian featuring Canadian singer Emjay

- "As Above, So Below", a song from the Klaxons' debut album Myths of the Near Future

- "As Above, So Below", a song from the Tom Tom Club's debut album Tom Tom Club

- "As Above, So Below", a song from The Comsat Angels' album Land

- "As Above, So Below", a song from Behemoth's album Zos Kia Cultus

- "As Above, So Below", a song from Yngwie Malmsteen's debut album Rising Force

See also

References

- Kraus, Paul 1942-1943. Jâbir ibn Hayyân: Contribution à l'histoire des idées scientifiques dans l'Islam. I. Le corpus des écrits jâbiriens. II. Jâbir et la science grecque. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale, vol. II, pp. 274-275; Weisser, Ursula 1980. Das Buch über das Geheimnis der Schöpfung von Pseudo-Apollonios von Tyana. Berlin: De Gruyter, p. 54.

- Steele, Robert and Singer, Dorothea Waley 1928. “The Emerald Table” in: Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, 21, pp. 41–57/485–501, p. 42/486 (English), p. 48/492 (Latin). For other medieval translations, see Emerald Tablet.

- Principe, Lawrence M. 2013. The Secrets of Alchemy. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, p. 198; Van Gijsen, Annelies 2006. "Astrology I: Introduction" in: Hanegraaff, Wouter J. et al. (eds.). Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism. Leiden/Boston: Brill, pp. 109-110.

- Steele, Robert and Singer, Dorothea Waley 1928. “The Emerald Table” in: Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, 21, p. 42/486; Principe, Lawrence M. 2013. The Secrets of Alchemy. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, p. 32. On the macrocosm and the microcosm, see, e.g., Conger, George Perrigo 1922. Theories of Macrocosms and Microcosms in the History of Philosophy. New York: Columbia University Press; Allers, Rudolf 1944. “Microcosmus: From Anaximandros to Paracelsus” in: Traditio, 2, pp. 319-407; Barkan, Leonard 1975. Nature’s Work of Art: The Human Body as Image of the World. London/New Haven: Yale University Press.

- This verse is identical in the earliest version (from pseudo-Apollonius of Tyana's Sirr al-khalīqa or The Secret of Creation) and in the slightly later version quoted by Jabir ibn Hayyan. See Weisser, Ursula 1979. Buch über das Geheimnis der Schöpfung und die Darstellung der Natur (Buch der Ursachen) von Pseudo-Apollonios von Tyana. Aleppo: Institute for the History of Arabic Science, p. 524; Zirnis, Peter 1979. The Kitāb Usṭuqus al-uss of Jābir ibn Ḥayyān. Unpublished PhD diss., New York University, p. 90.

- Hudry, Françoise 1997-1999. “Le De secretis nature du Ps. Apollonius de Tyane, traduction latine par Hugues de Santalla du Kitæb sirr al-halîqa” in: Chrysopoeia, 6, pp. 1-154, p. 152.

- Holmyard, Eric J. 1923. "The Emerald Table" in: Nature, 122, pp. 525-526. (translation of the version quoted by Jabir ibn Hayyan)

Petreius, Johannes 1541. De alchemia. Nuremberg, p. 363; (available online)