| Revision as of 06:49, 13 September 2004 view sourceAndres (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users12,370 editsm et:← Previous edit | Revision as of 11:09, 16 September 2004 view source 213.6.251.144 (talk)No edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

| A religious revolutionary, he eschewed (but did not abandon) the traditional pantheon of deities, and worshipped the sun-god ]. He oversaw the construction of some of the most massive temple complexes in ancient Egypt in honor of Aten. The idea of Akhenaten as the pioneer of ] was promoted by ] (the founder of ]) in his book ''Moses and Monotheism'' and thereby entered popular consciousness. | A religious revolutionary, he eschewed (but did not abandon) the traditional pantheon of deities, and worshipped the sun-god ]. He oversaw the construction of some of the most massive temple complexes in ancient Egypt in honor of Aten. The idea of Akhenaten as the pioneer of ] was promoted by ] (the founder of ]) in his book ''Moses and Monotheism'' and thereby entered popular consciousness. | ||

| This view is not shared by many egyptologists; ] may be a better description of Egyptian religion. Although it also might not be a coincidence that he introduced monotheism, and quoted the Psalms of Moses. Could it be that he began to worship the God of the Israelites? Sources indicate that the 13 long lines of the poem were praise for Aten as the creator and preserver of the world. Within it, there are no allusions to traditional mythical concepts since the names of the other gods are absent. Even the plural form of the word god was avoided. Akhenaten also ordered the closure of the temples dedicated to all the other gods in Egypt. Not only were these temples closed, but in order to extinguish the memory of these gods as much as possible, a veritable persecution took place. Literal armies of stonemasons were sent out all over the land and even into Nubia, above all else, to hack away the image and name of the god Amun. | |||

| This view is not shared by many egyptologists; ] may be a better description of Egyptian religion. | |||

| Aten was removed from the Egyptian pantheon, and Akhenaten as well as his family and religion, were now the focus of prosecution. Their monuments were destroyed, together with related inscriptions and images, as in the case of Hatshepsut. | |||

| It is said that one day, the high priest, Ay, led in the priests of Amon and killed the entire family except the 6 daughters, seeing as he himself was still a devout follower of Amun, despite the new religion of the pharaoh. The youngest daughter was in love with Tutankaten. They were allowed to marry, and Tutankaten reigned for only a short while before dying. But before he died, he changed his name to Tutankamun (which indicates that he was probably asked to change his religion or die, and he chose to change his name). His wife, now widow, had also changed her name from Akensenpaaten to Akensenamun. She wrote a letter to the Hittite king asking him to allow her to marry one of her sons, but the king refused. So Akensenamun married Ay, the self-pronounced pharaoh, and ex-high priest. | |||

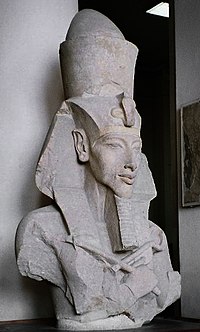

| Styles of art that flourished during this short period are markedly different from other Egyptian art, bearing a variety of affectations, from elongated heads to protruding stomachs, exaggerated ugliness and the beauty of Nefertiti. Artistic representations of Akhenaten give him a very feminine appearance, giving rise to controversial theories such that he may have actually been a woman masquerading as a man, which had been known to happen in Egyptian politics once or twice, or that he was a ] or had some other phenotypic sexual disorder. There is circumstantial evidence that he was ] and had many lovers of both sexes, after Nefertiti disappeared from the historical record. It is also suggested by Bob Brier, in his book "The Murder of Tutankhamen", that his family suffered from ], which is known to cause elongated features and may explain his appearance. | Styles of art that flourished during this short period are markedly different from other Egyptian art, bearing a variety of affectations, from elongated heads to protruding stomachs, exaggerated ugliness and the beauty of Nefertiti. Artistic representations of Akhenaten give him a very feminine appearance, giving rise to controversial theories such that he may have actually been a woman masquerading as a man, which had been known to happen in Egyptian politics once or twice, or that he was a ] or had some other phenotypic sexual disorder. There is circumstantial evidence that he was ] and had many lovers of both sexes, after Nefertiti disappeared from the historical record. It is also suggested by Bob Brier, in his book "The Murder of Tutankhamen", that his family suffered from ], which is known to cause elongated features and may explain his appearance. | ||

Revision as of 11:09, 16 September 2004

Akhenaten – alternatively spelled Akhnaten, Akhenaton, Akhnaton, Ikhnaton, and so on; known as Amenhotep IV at the start of his reign; and called Naphu(`)rureya in the Amarna letters – was a Pharaoh of the Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt. He is thought to have been born to Amenhotep III and his Chief Queen Tiy in the year 26 of their reign (1379 BC or 1362 BC). He succeeded his father in year 38 and last of his reign (1367 BC or 1350 BC) at the age of twelve. He reigned from 1367 BC to 1350 BC or from 1350 BC/1349 BC to 1334 BC/ 1333 BC during the Eighteenth Dynasty. His chief wife was Nefertiti, who has been made famous by her bust in the Ägyptisches Museum in Berlin.

The exact dates for Amenhotep IV's marriage to Nefertiti are uncertain. However the couple had six known daughters. This is a list with suggested years of birth:

- Meritaten – year 2 (1366 BC or 1348 BC).

- Meketaten – year 3 (1365 BC or 1347 BC).

- Ankhesenpaaten, later Queen of Tutankhamun – year 4 (1364 BC or1346 BC).

- Neferneferuaten Tasherit – year 6 (1362 BC or 1344 BC).

- Neferneferure – year 9 (1359 BC or 1341 BC).

- Setepenre – year 11 (1357 BC or 1339 BC).

In year 4 of his reign (1364 BC or 1346 BC) Amenhotep IV started his famous worship of Aten. This year is also believed to mark the beginning of his construction of a new capital, Akhetaten, at the site known today as Amarna. In year 5 of his reign (1363 BC or 1345 BC) Amenhotep IV officially changed his name to Akhenaten as evidence of his new worship. The date given for the event has been estimated to fall around January 2 of that year. In year 7 of his reign (1361 BC or 1343 BC) the capital was moved from Thebes to Amarna, though construction of the city seems to have continued for two more years (till 1359 BC or 1341 BC). The new city was dedicated to the royal couple's new religion.

A religious revolutionary, he eschewed (but did not abandon) the traditional pantheon of deities, and worshipped the sun-god Aten. He oversaw the construction of some of the most massive temple complexes in ancient Egypt in honor of Aten. The idea of Akhenaten as the pioneer of monotheistic religion was promoted by Sigmund Freud (the founder of psychoanalysis) in his book Moses and Monotheism and thereby entered popular consciousness. This view is not shared by many egyptologists; henotheism may be a better description of Egyptian religion. Although it also might not be a coincidence that he introduced monotheism, and quoted the Psalms of Moses. Could it be that he began to worship the God of the Israelites? Sources indicate that the 13 long lines of the poem were praise for Aten as the creator and preserver of the world. Within it, there are no allusions to traditional mythical concepts since the names of the other gods are absent. Even the plural form of the word god was avoided. Akhenaten also ordered the closure of the temples dedicated to all the other gods in Egypt. Not only were these temples closed, but in order to extinguish the memory of these gods as much as possible, a veritable persecution took place. Literal armies of stonemasons were sent out all over the land and even into Nubia, above all else, to hack away the image and name of the god Amun. Aten was removed from the Egyptian pantheon, and Akhenaten as well as his family and religion, were now the focus of prosecution. Their monuments were destroyed, together with related inscriptions and images, as in the case of Hatshepsut.

It is said that one day, the high priest, Ay, led in the priests of Amon and killed the entire family except the 6 daughters, seeing as he himself was still a devout follower of Amun, despite the new religion of the pharaoh. The youngest daughter was in love with Tutankaten. They were allowed to marry, and Tutankaten reigned for only a short while before dying. But before he died, he changed his name to Tutankamun (which indicates that he was probably asked to change his religion or die, and he chose to change his name). His wife, now widow, had also changed her name from Akensenpaaten to Akensenamun. She wrote a letter to the Hittite king asking him to allow her to marry one of her sons, but the king refused. So Akensenamun married Ay, the self-pronounced pharaoh, and ex-high priest.

Styles of art that flourished during this short period are markedly different from other Egyptian art, bearing a variety of affectations, from elongated heads to protruding stomachs, exaggerated ugliness and the beauty of Nefertiti. Artistic representations of Akhenaten give him a very feminine appearance, giving rise to controversial theories such that he may have actually been a woman masquerading as a man, which had been known to happen in Egyptian politics once or twice, or that he was a hermaphrodite or had some other phenotypic sexual disorder. There is circumstantial evidence that he was bisexual and had many lovers of both sexes, after Nefertiti disappeared from the historical record. It is also suggested by Bob Brier, in his book "The Murder of Tutankhamen", that his family suffered from Marfan's syndrome, which is known to cause elongated features and may explain his appearance.

Of his known or suggested lovers the most memorable are:

- Tiy, his mother. Twelve years after the death of Amenhotep III she is still mentioned in inscriptions as Queen and beloved of the King. It has been suggested that Akhenaten and his mother acted as consorts to each other till her death. This would be considered incest at the time. Supporters of this theory consider Akhenaten to be the historical model of legendary King Oedipus of Thebes, Greece and Tiy the model for his mother/wife Jocasta.

- Nefertiti, his first queen.

- Kiya, his second queen.

- Smenkhkare, his co-ruler for the last years of his reign (1354 BC or 1336 BC till 1350 BC or 1334 BC/ 1333 BC. He is thought to have been a half-brother or a son to Akhenaten but also a lover. Some have suggested that Smenkhkare was actually an alias of Nefertiti or Kiya and therefore a woman.

- Ankhesenpaaten, his third daughter and last known wife at during the last year of his life. After his death she married his successor Tutankhamun.

Both Smenkhkare, his co-ruler, and Akhenaten himself died in year 17 of his reign (1350 BC or 1334 BC/1333 BC); the order of events is still unclear. They were succeeded by Tutankhaten (later, Tutankhamun). The new Pharaoh is believed to be a younger brother of Smenkhkare and a son of either Amenhotep III or Akhenaten. With Akhenaten's death the Sun God cult he had founded almost immediately fell out of favor. Tutankhaten changed his name to Tutankhamun in year 3 of his reign (1349 BC and 1331 BC) and abandoned Amarna. Aten's cult seems to have been the target of considerable official hostility after that. Temples he had built were disassembled by his successors Ay and Horemheb as a source of easily available building materials and decorations for their own temples. Akhenaten, Smenkhkare, Tutankhamun, and Ay were omitted from the official lists of Pharaohs, which instead reported that Amenhotep III was immediately succeeded by Horemheb. This is thought to reflect an attempt by Horemheb to delete his predecessors from the historical record.

Akhenaten in the Arts

- Mika Waltari: novel The Egyptian (1945)

- Philip Glass: opera Akhnaten (1983)

- Naguib Mahfouz: novel Akhenaten, Dweller in Truth (1985)

- Allen Drury, historical novels A God Against the Gods (Doubleday, 1976) and Return to Thebes (Doubleday, 1976)

- Judith Tarr, historical fantasy Pillar of Fire (1995)

- Lynda Robinson, historical mystery Drinker of Blood (2001, ISBN 0446677515)

Further reading

- Donald B. Redford: Akhenaten : The Heretic King (Princeton University Press, 1984)

- Cyril Aldred: Akhenaten: King of Egypt (Thames & Hudson, 1988)

- Rita E. Freed, Yvonne J. Markowitz, Sue H. D'Auria, Pharaohs of the Sun: Akhenaten - Nefertiti - Tutankhamen (Museum of Fine Arts, 1999)

- Dominic Montserrat, Akhenaten: History, Fantasy and Ancient Egypt, (Routledge, 2000)

- Nicholas Reeves, Akhenaten: Egypt's False Prophet, (Thames and Hudson, 2001)

External links

- Akhenaten and the Hymn to the Aten

- A more detailed profile of him

- A profile discussing his familial relations