1970s in history refers to significant events in the 1970s.

World events

Vietnam War

This section is an excerpt from Vietnam War.]

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam was supported by the Soviet Union and China, while South Vietnam was supported by the United States and other anti-communist nations. The conflict was the second of the Indochina Wars and a major proxy war of the Cold War between the Soviet Union and US. Direct US military involvement greatly escalated from 1965 until its withdrawal in 1973. The fighting spilled over into the Laotian and Cambodian Civil Wars, which ended with all three countries becoming communist in 1975.

After the defeat of French Indochina in the First Indochina War that began in 1946, Vietnam gained independence in the 1954 Geneva Conference but was divided into two parts at the 17th parallel: the Viet Minh, led by Ho Chi Minh, took control of North Vietnam, while the US assumed financial and military support for South Vietnam, led by Ngo Dinh Diem. The North Vietnamese began supplying and directing the Viet Cong (VC), a common front of dissidents in the south, which intensified a guerrilla war from 1957. In 1958, North Vietnam invaded Laos, establishing the Ho Chi Minh trail to supply and reinforce the VC. By 1963, the north had covertly sent 40,000 soldiers of its own People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN), armed with Soviet and Chinese weapons, to fight in the insurgency in the south. President John F. Kennedy increased US involvement from 900 military advisors in 1960 to 16,300 in 1963 and sent more aid to the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), which failed to produce results. In 1963, Diem was killed in a US-backed military coup, which added to the south's instability.

Following the Gulf of Tonkin incident in 1964, the US Congress passed a resolution that gave President Lyndon B. Johnson authority to increase military presence without a declaration of war. Johnson launched a bombing campaign of the north and began sending combat troops, dramatically increasing deployment to 184,000 by the end of 1965, and to 536,000 by the end of 1968. US forces relied on air supremacy and overwhelming firepower to conduct search and destroy operations in rural areas. In 1968, North Vietnam launched the Tet Offensive, which was a tactical defeat but convinced many in the US that the war could not be won. The PAVN began engaging in more conventional warfare. Johnson's successor, Richard Nixon, began a policy of "Vietnamization" from 1969, which saw the conflict fought by an expanded ARVN, while US forces withdrew. A 1970 coup in Cambodia resulted in a PAVN invasion and a US–ARVN counter-invasion, escalating its civil war. US troops had mostly withdrawn from Vietnam by 1972, and the 1973 Paris Peace Accords saw the rest leave. The accords were broken almost immediately and fighting continued until the 1975 spring offensive and fall of Saigon to the PAVN, marking the war's end. North and South Vietnam were reunified in 1976.

The war exacted enormous human cost: estimates of Vietnamese soldiers and civilians killed range from 970,000 to 3 million. Some 275,000–310,000 Cambodians, 20,000–62,000 Laotians, and 58,220 US service members died. Its end would precipitate the Vietnamese boat people and the larger Indochina refugee crisis, which saw millions leave Indochina, an estimated 250,000 perished at sea. The US destroyed 20% of South Vietnam's jungle and 20–50% of the mangrove forests, by spraying over 20 million U.S. gallons (75 million liters) of toxic herbicides; a notable example of ecocide. The Khmer Rouge carried out the Cambodian genocide, while conflict between them and the unified Vietnam escalated into the Cambodian–Vietnamese War. In response, China invaded Vietnam, with border conflicts lasting until 1991. Within the US, the war gave rise to Vietnam syndrome, a public aversion to American overseas military involvement, which, with the Watergate scandal, contributed to the crisis of confidence that affected America throughout the 1970s.Yom Kippur War

This section is an excerpt from Yom Kippur War.

The Yom Kippur War, also known as the Ramadan War, the October War, the 1973 Arab–Israeli War, or the Fourth Arab–Israeli War, was fought from 6 to 25 October 1973 between Israel and a coalition of Arab states led by Egypt and Syria. Most of the fighting occurred in the Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights, territories occupied by Israel in 1967. Some combat also took place in Egypt and northern Israel. Egypt aimed to secure a foothold on the eastern bank of the Suez Canal and use it to negotiate the return of the Sinai Peninsula.

The war started on 6 October 1973, when the Arab coalition launched a surprise attack on Israel during the Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur, which coincided with the 10th day of Ramadan. The United States and Soviet Union engaged in massive resupply efforts for their allies (Israel and the Arab states, respectively), which heightened tensions between the two superpowers.

Egyptian and Syrian forces crossed their respective ceasefire lines with Israel, advancing into the Sinai and Golan Heights. Egyptian forces crossed the Suez Canal in Operation Badr and advanced into the Sinai, while Syrian forces gained territory in the Golan Heights. After three days, Israel halted the Egyptian advance and pushed most of the Syrians back to the Purple line. Israel then launched a counteroffensive into Syria, shelling the outskirts of Damascus.

Egyptian forces attempted to push further into Sinai but were repulsed, and Israeli forces crossed the Suez Canal, advancing toward Ismailia City on 18 October. Israeli forces were then defeated in the Battle of Ismailia and accepted a UN-brokered ceasefire. On 22 October, the ceasefire broke down. Initially both sides accused each other of violations, however declassified documents revealed the United States had given Israel permission to breach the ceasefire and encircle the Egyptian Third Army and Suez City. Israeli forces then advanced on Suez City, but were successfully repulsed in the ensuing battle amid stiff Egyptian resistance. A second ceasefire was imposed on 25 October, officially ending the war.

The Yom Kippur War had significant consequences. The Arab world, humiliated by the 1967 defeat, felt psychologically vindicated by its early and late successes in 1973. Meanwhile, Israel, despite battlefield achievements, recognized that future military dominance was uncertain. These shifts contributed to the Israeli–Palestinian peace process, leading to the 1978 Camp David Accords, when Israel returned the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt, and the Egypt–Israel peace treaty, the first time an Arab country recognized Israel. Egypt drifted away from the Soviet Union, eventually leaving the Eastern Bloc.

Oil crisis

This section is an excerpt from 1970s energy crisis.The 1970s energy crisis occurred when the Western world, particularly the United States, Canada, Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand, faced substantial petroleum shortages as well as elevated prices. The two worst crises of this period were the 1973 oil crisis and the 1979 energy crisis, when, respectively, the Yom Kippur War and the Iranian Revolution triggered interruptions in Middle Eastern oil exports.

The crisis began to unfold as petroleum production in the United States and some other parts of the world peaked in the late 1960s and early 1970s. World oil production per capita began a long-term decline after 1979. The oil crises prompted the first shift towards energy-saving (in particular, fossil fuel-saving) technologies.

The major industrial centers of the world were forced to contend with escalating issues related to petroleum supply. Western countries relied on the resources of countries in the Middle East and other parts of the world. The crisis led to stagnant economic growth in many countries as oil prices surged. Although there were genuine concerns with supply, part of the run-up in prices resulted from the perception of a crisis. The combination of stagnant growth and price inflation during this era led to the coinage of the term stagflation. By the 1980s, both the recessions of the 1970s and adjustments in local economies to become more efficient in petroleum usage, controlled demand sufficiently for petroleum prices worldwide to return to more sustainable levels.

The period was not uniformly negative for all economies. Petroleum-rich countries in the Middle East benefited from increased prices and the slowing production in other areas of the world. Some other countries, such as Norway, Mexico, and Venezuela, benefited as well. In the United States, Texas and Alaska, as well as some other oil-producing areas, experienced major economic booms due to soaring oil prices even as most of the rest of the nation struggled with the stagnant economy. Many of these economic gains, however, came to a halt as prices stabilized and dropped in the 1980s.Science and Technology

Air travel

See also: Jet travel This section is an excerpt from Wide-body aircraft § 1970s.The wide-body age of jet travel began in 1970 with the entry into service of the first wide-body airliner, the four-engined, partial double-deck Boeing 747. New trijet wide-body aircraft soon followed, including the McDonnell Douglas DC-10 and the L-1011 TriStar. The first wide-body twinjet, the Airbus A300, entered service in 1974. This period came to be known as the "wide-body wars".

L-1011 TriStars were demonstrated in the USSR in 1974, as Lockheed sought to sell the aircraft to Aeroflot. However, in 1976 the Soviet Union launched its own first four-engined wide-body, the Ilyushin Il-86.

After the success of the early wide-body aircraft, several subsequent designs came to market over the next two decades, including the Boeing 767 and 777, the Airbus A330 and Airbus A340, and the McDonnell Douglas MD-11. In the "jumbo" category, the capacity of the Boeing 747 was not surpassed until October 2007, when the Airbus A380 entered commercial service with the nickname "Superjumbo". Both the Boeing 747 and Airbus A380 "jumbo jets" have four engines each (quad-jets), but the upcoming Boeing 777X ("mini jumbo jet") is a twinjet.

In the mid-2000s, rising oil costs in a post-9/11 climate caused airlines to look towards newer, more fuel-efficient aircraft. Two such examples are the Boeing 787 Dreamliner and Airbus A350 XWB. The proposed Comac C929 and C939 may also share this new wide-body market.

Africa

Tanzania

This section is an excerpt from Julius Nyerere.

Julius Kambarage Nyerere (Swahili pronunciation: [ˈdʒulius kɑᵐbɑˈɾɑɠɛ ɲɛˈɾɛɾɛ]; 13 April 1922 – 14 October 1999) was a Tanzanian anti-colonial activist, politician and political theorist. He governed Tanganyika as prime minister from 1961 to 1962 and then as president from 1962 to 1964, after which he led its successor state, Tanzania, as president from 1964 to 1985. He was a founding member and chair of the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) party, and of its successor, Chama Cha Mapinduzi, from 1954 to 1990. Ideologically an African nationalist and African socialist, he promoted a political philosophy known as Ujamaa.

Born in Butiama, Mara, then in the British colony of Tanganyika, Nyerere was the son of a Zanaki chief. After completing his schooling, he studied at Makerere College in Uganda and then Edinburgh University in Scotland. In 1952 he returned to Tanganyika, married, and worked as a school teacher. In 1954, he helped form TANU, through which he campaigned for Tanganyikan independence from the British Empire. Influenced by the Indian independence leader Mahatma Gandhi, Nyerere preached non-violent protest to achieve this aim. Elected to the Legislative Council in the 1958–1959 elections, Nyerere then led TANU to victory at the 1960 general election, becoming prime minister. Negotiations with the British authorities resulted in Tanganyikan independence in 1961. In 1962, Tanganyika became a republic, with Nyerere elected as its first president. His administration pursued decolonisation and the "Africanisation" of the civil service while promoting unity between indigenous Africans and the country's Asian and European minorities. He encouraged the formation of a one-party state and unsuccessfully pursued the Pan-Africanist formation of an East African Federation with Uganda and Kenya. A 1963 mutiny within the army was suppressed with British assistance.

Following the Zanzibar Revolution of 1964, the island of Zanzibar was unified with Tanganyika to form Tanzania. After this, Nyerere placed a growing emphasis on national self-reliance and socialism. Although his socialism differed from that promoted by Marxism–Leninism, Tanzania developed close links with Mao Zedong's China. In 1967, Nyerere issued the Arusha Declaration which outlined his vision of ujamaa. Banks and other major industries and companies were nationalized; education and healthcare were significantly expanded. Renewed emphasis was placed on agricultural development through the formation of communal farms, although these reforms hampered food production and left areas dependent on food aid. His government provided training and aid to anti-colonialist groups fighting white-minority rule throughout southern Africa and oversaw Tanzania's 1978–1979 war with Uganda which resulted in the overthrow of Ugandan President Idi Amin. In 1985, Nyerere stood down and was succeeded by Ali Hassan Mwinyi, who reversed many of Nyerere's policies. He remained chair of Chama Cha Mapinduzi until 1990, supporting a transition to a multi-party system, and later served as mediator in attempts to end the Burundian Civil War.

Nyerere was a controversial figure. Across Africa he gained widespread respect as an anti-colonialist and in power received praise for ensuring that, unlike many of its neighbours, Tanzania remained stable and unified in the decades following independence. His construction of the one-party state and use of detention without trial led to accusations of dictatorial governance, while he has also been blamed for economic mismanagement. He is held in deep respect within Tanzania, where he is often referred to by the Swahili honorific Mwalimu ("teacher") and described as the "Father of the Nation".

Uganda

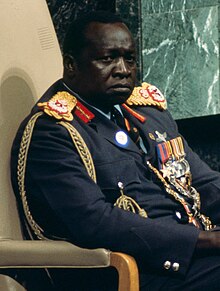

This section is an excerpt from Idi Amin.

Idi Amin Dada Oumee (/ˈiːdi ɑːˈmiːn, ˈɪdi -/ , UK also /- æˈmiːn/; 30 May 1928 – 16 August 2003) was a Ugandan military officer and politician who served as the third president of Uganda from 1971 to 1979. He ruled as a military dictator and is considered one of the most brutal despots in modern world history.

Amin was born to a Kakwa father and Lugbara mother. In 1946, he joined the King's African Rifles (KAR) of the British Colonial Army as a cook. He rose to the rank of lieutenant, taking part in British actions against Somali rebels and then the Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya. Uganda gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1962, and Amin remained in the army, rising to the position of deputy army commander in 1964 and being appointed commander two years later. He became aware that Ugandan President Milton Obote was planning to arrest him for misappropriating army funds, so he launched the 1971 Ugandan coup d'état and declared himself president.

During his years in power, Amin shifted from being a pro-Western ruler enjoying considerable support from Israel to being backed by Libya's Muammar Gaddafi, Zaire's Mobutu Sese Seko, the Soviet Union, and East Germany. In 1972, Amin expelled Asians, a majority of whom were Indian-Ugandans, leading India to sever diplomatic relations with his regime. In 1975, Amin assumed chairmanship of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), a Pan-African group designed to promote solidarity among African states (an annually rotating role). Uganda was a member of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights from 1977 to 1979. The United Kingdom broke diplomatic relations with Uganda in 1977, and Amin declared that he had defeated the British and added "CBE" to his title for "Conqueror of the British Empire".

As Amin's rule progressed into the late 1970s, there was increased unrest against his persecution of certain ethnic groups and political dissidents, along with Uganda's very poor international standing due to Amin's support for PFLP-EO and RZ hijackers in 1976, leading to Israel's Operation Entebbe. He then attempted to annex Tanzania's Kagera Region in 1978. Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere ordered his troops to invade Uganda in response. Tanzanian Army and rebel forces successfully captured Kampala in 1979 and ousted Amin from power. Amin went into exile, first in Libya, then Iraq, and finally in Saudi Arabia, where he lived until his death in 2003.

Amin's rule was characterized by rampant human rights abuses, including political repression, ethnic persecution, extrajudicial killings, as well as nepotism, corruption, and gross economic mismanagement. International observers and human rights groups estimate that between 100,000 and 500,000 people were killed under his regime.

Zaire

This section is an excerpt from Mobutu Sese Seko.

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Early political career Presidency

|

||

Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu wa za Banga (/məˈbuːtuː ˈsɛseɪ ˈsɛkoʊ/ mə-BOO-too SESS-ay SEK-oh; born Joseph-Désiré Mobutu; 14 October 1930 – 7 September 1997), often shortened to Mobutu Sese Seko or Mobutu and also known by his initials MSS, was a Congolese politician and military officer who was the first and only president of Zaire from 1971 to 1997. Previously, Mobutu served as the second president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1965 to 1971. He also served as the fifth chairperson of the Organisation of African Unity from 1967 to 1968. During the Congo Crisis, Mobutu, serving as Chief of Staff of the Army and supported by Belgium and the United States, deposed the democratically elected government of left-wing nationalist Patrice Lumumba in 1960. Mobutu installed a government that arranged for Lumumba's execution in 1961, and continued to lead the country's armed forces until he took power directly in a second coup in 1965.

To consolidate his power, he established the Popular Movement of the Revolution as the sole legal political party in 1967, changed the Congo's name to Zaire in 1971, and his own name to Mobutu Sese Seko in 1972. Mobutu claimed that his political ideology was "neither left nor right, nor even centre", though nevertheless he developed a regime that was intensely autocratic. He attempted to purge the country of all colonial cultural influence through his program of "national authenticity". Mobutu was the object of a pervasive cult of personality. During his rule, he amassed a large personal fortune through economic exploitation and corruption, leading some to call his rule a "kleptocracy". He presided over a period of widespread human rights violations. Under his rule, the nation also suffered from uncontrolled inflation, a large debt, and massive currency devaluations.

Mobutu received strong support (military, diplomatic and economic) from the United States, France, and Belgium, who believed he was a strong opponent of communism in Francophone Africa. He also built close ties with the governments of apartheid South Africa, Israel and the Greek junta. From 1972 onward, he was also supported by Mao Zedong of China, mainly due to his anti-Soviet stance but also as part of Mao's attempts to create a bloc of Afro-Asian nations led by him. The massive Chinese economic aid that flowed into Zaire gave Mobutu more flexibility in his dealings with Western governments, allowed him to identify as an "anti-capitalist revolutionary", and enabled him to avoid going to the International Monetary Fund for assistance.

By 1990, economic deterioration and unrest forced Mobutu Sese Seko into coalition with his power opponents. Although he used his troops to thwart change, his antics did not last long. In May 1997, rebel forces led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila overran the country and forced him into exile. Already suffering from advanced prostate cancer, he died three months later in Morocco. Mobutu was notorious for corruption and nepotism: estimates of his personal wealth range from $50 million to $5 billion. He was known for extravagances such as shopping trips to Paris via the supersonic Concorde aircraft.Asia

China

This section is an excerpt from Mao Zedong.

Mao Zedong (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) and led the country from its establishment in 1949 until his death in 1976. Mao also served as the chairman of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from 1943 until his death, and as the party's de facto leader from 1935. His theories, which he advocated as a Chinese adaptation of Marxism–Leninism, are known as Maoism.

Mao was the son of a peasant in Shaoshan, Hunan. He was influenced early in his life by the events of the 1911 Revolution and May Fourth Movement of 1919, supporting Chinese nationalism and anti-imperialism. He later adopted Marxism–Leninism while working as a librarian at Peking University, and in 1921 was a founding member of the Chinese Communist Party. After the start of the Chinese Civil War between the Kuomintang (KMT) and CCP in 1927, Mao led the failed Autumn Harvest Uprising and founded the Jiangxi Soviet. He helped establish the Chinese Red Army and developed a strategy of guerilla warfare. In 1935, Mao became the leader of the CCP during the Long March. Although the CCP allied with the KMT under the Second United Front during the Second Sino-Japanese War, China's civil war resumed after Japan's surrender in 1945; Mao's forces defeated the Nationalist government, which withdrew to Taiwan in 1949.

On 1 October 1949, Mao proclaimed the foundation of the PRC, a one-party state controlled by the CCP. He initiated campaigns of land redistribution and industrialisation, suppressed counter-revolutionaries, intervened in the Korean War, and began the Hundred Flowers and Anti-Rightist Campaigns. In 1958, Mao launched the Great Leap Forward, which aimed to transform China's economy from agrarian to industrial; it resulted in Great Chinese Famine. In 1966, Mao initiated the Cultural Revolution, a campaign to remove "counter-revolutionary" elements, marked by violent class struggle, destruction of historical artifacts, and Mao's cult of personality. From the late 1950s, Mao's foreign policy was dominated by a political split with the Soviet Union, and during the 1970s he began establishing relations with the United States; China was also involved in the Vietnam War and Cambodian Civil War. In 1976, Mao died after suffering a series of heart attacks. He was succeeded as leader by Hua Guofeng and in 1978 by Deng Xiaoping. The CCP's official evaluation of Mao's legacy both praises him and acknowledges he made errors in his later years.

Mao is considered one of the most significant figures of the 20th century. His policies were responsible for a vast number of deaths, with estimates ranging from 40 to 80 million victims of starvation, persecution, prison labour, and mass executions, and his regime has been described as totalitarian. He has been also credited with transforming China from a semi-colony to a leading world power by advancing literacy, women's rights, basic healthcare, primary education, and life expectancy. Under Mao, China's population grew from about 550 million to more than 900 million. Within China, he is revered as a national hero who liberated the country from foreign occupation and exploitation. He became an ideological figurehead and a prominent influence within the international communist movement, inspiring various Maoist organisations.India

This section is an excerpt from Indira Gandhi.

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Prime Minister of India1966–1977 1980–1984

National policy Legislation

Treaties and accords Missions and projects

Controversies Riots and attacks

Constitutional amendments

Gallery: Picture, Sound, Video

Gallery: Picture, Sound, Video |

||

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (Hindi: [ˈɪndɪɾɑː ˈɡɑːndʱi] ; née Indira Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and stateswoman who served as the Prime Minister of India from 1966 to 1977 and again from 1980 until her assassination in 1984. She was India's first and, to date, only female prime minister, and a central figure in Indian politics as the leader of the Indian National Congress (INC). She was the daughter of Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of India, and the mother of Rajiv Gandhi, who succeeded her in office as the country's sixth prime minister. Gandhi's cumulative tenure of 15 years and 350 days makes her the second-longest-serving Indian prime minister after her father. Henry Kissinger described her as an "Iron Lady", a nickname that became associated with her tough personality.

During Nehru's premiership from 1947 to 1964, Gandhi was his hostess and accompanied him on his numerous foreign trips. In 1959, she played a part in the dissolution of the communist-led Kerala state government as then-president of the Indian National Congress, otherwise a ceremonial position to which she was elected earlier that year. Lal Bahadur Shastri, who had succeeded Nehru as prime minister upon his death in 1964, appointed her minister of information and broadcasting in his government; the same year she was elected to the Rajya Sabha, the upper house of the Indian Parliament. After Shastri's sudden death in January 1966, Gandhi defeated her rival, Morarji Desai, in the INC's parliamentary leadership election to become leader and also succeeded Shastri as prime minister. She led the Congress to victory in two subsequent elections, starting with the 1967 general election, in which she was first elected to the lower house of the Indian parliament, the Lok Sabha. In 1971, her party secured its first landslide victory since her father's sweep in 1962, focusing on issues such as poverty. But following the nationwide state of emergency she implemented, she faced massive anti-incumbency sentiment causing the INC to lose the 1977 election, the first time in the history of India to happen so. She even lost her own parliamentary constituency. However, due to her portrayal as a strong leader and the weak governance of the Janata Party, her party won the next election by landslide with her return to the premiership.

As prime minister, Gandhi was known for her uncompromising political stances and centralization of power within the executive branch. In 1967, she headed a military conflict with China in which India repelled Chinese incursions into the Himalayas. In 1971, she went to war with Pakistan in support of the independence movement and war of independence in East Pakistan, which resulted in an Indian victory and the independence of Bangladesh, as well as increasing India's influence to the point where it became the sole regional power in South Asia. She played a crucial role in initiating India's first successful nuclear weapon test in 1974. Her rule saw India grow closer to the Soviet Union by signing a friendship treaty in 1971, with India receiving military, financial, and diplomatic support from the Soviet Union during its conflict with Pakistan in the same year. Though India was at the forefront of the non-aligned movement, Gandhi made it one of the Soviet Union's closest allies in Asia, each often supporting the other in proxy wars and at the United Nations. Responding to separatist tendencies and a call for revolution, she instituted a state of emergency from 1975 to 1977, during which she ruled by decree and basic civil liberties were suspended. More than 100,000 political opponents, journalists and dissenters were imprisoned. She faced the growing Sikh separatism movement throughout her fourth premiership; in response, she ordered Operation Blue Star, which involved military action in the Golden Temple and killed hundreds of Sikhs. On 31 October 1984, she was assassinated by two of her bodyguards, both of whom were Sikh nationalists seeking retribution for the events at the temple.

Gandhi is remembered as the most powerful woman in the world during her tenure. Her supporters cite her leadership during victories over geopolitical rivals China and Pakistan, the Green Revolution, a growing economy in the early 1980s, and her anti-poverty campaign that led her to be known as "Mother Indira" (a pun on Mother India) among the country's poor and rural classes. Critics note her cult of personality and authoritarian rule of India during the Emergency. In 1999, she was named "Woman of the Millennium" in an online poll organized by the BBC. In 2020, she was named by Time magazine among the 100 women who defined the past century as counterparts to the magazine's previous choices for Man of the Year.

Japan

Europe

Russia

This section is an excerpt from Alexei Kosygin.Alexei Nikolayevich Kosygin (Russian: Алексе́й Никола́евич Косы́гин, IPA: [ɐlʲɪkˈsʲej nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ kɐˈsɨɡʲɪn]; 21 February [O.S. 8 February] 1904 – 18 December 1980) was a Soviet statesman during the Cold War. He served as the Premier of the Soviet Union from 1964 to 1980 and was one of the most influential Soviet policymakers in the mid-1960s along with General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev.

Kosygin was born in the city of Saint Petersburg in 1904 to a Russian working-class family. He was conscripted into the labour army during the Russian Civil War, and after the Red Army's demobilization in 1921, he worked in Siberia as an industrial manager. Kosygin returned to Leningrad in the early 1930s and worked his way up the Soviet hierarchy. During the Great Patriotic War (World War II), Kosygin was tasked by the State Defence Committee with moving Soviet industry out of territories soon to be overrun by the German Army. He served as Minister of Finance for a year before becoming Minister of Light Industry (later, Minister of Light Industry and Food). Stalin removed Kosygin from the Politburo one year before his own death in 1953, intentionally weakening Kosygin's position within the Soviet hierarchy.

Stalin died in 1953, and on 20 March 1959, Kosygin was appointed to the position of chairman of the State Planning Committee (Gosplan), a post he would hold for little more than a year. Kosygin next became First Deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers. When Nikita Khrushchev was removed from power in 1964, Kosygin and Leonid Brezhnev succeeded him as Premier and First Secretary, respectively. Thereafter, as a member of the collective leadership, Kosygin formed an unofficial Triumvirate (also known by its Russian name Troika) alongside Brezhnev and Nikolai Podgorny, the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, that governed the Soviet Union in Khrushchev's place.

During the initial years following Khrushchev's ouster, Kosygin initially emerged as the most prominent figure in the Soviet leadership. In addition to managing the Soviet Union's economy, he assumed a preeminent role in its foreign policy by leading arms control talks with the US and overseeing relations with Western countries in general. However, the onset of the Prague Spring in 1968 sparked a severe backlash against his policies, enabling Leonid Brezhnev to decisively eclipse him as the dominant force within the Politburo. While he and Brezhnev disliked one another, he remained in office until being forced to retire on 23 October 1980, due to bad health. He died two months later on 18 December 1980. This section is an excerpt from Leonid Brezhnev.

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

First, then General Secretary of the CPSU

Foreign policy  Media gallery

Media gallery |

||

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (19 December 1906 – 10 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 until his death in 1982, and Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet (head of state) from 1960 to 1964 and again from 1977 to 1982. His 18-year term as General Secretary was second only to Joseph Stalin's in duration.

Brezhnev was born to a working-class family in Kamenskoye (now Kamianske, Ukraine) within the Yekaterinoslav Governorate of the Russian Empire. After the results of the October Revolution were finalized with the creation of the Soviet Union, Brezhnev joined the Communist party's youth league in 1923 before becoming an official party member in 1929. When Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, he joined the Red Army as a commissar and rose rapidly through the ranks to become a major general during World War II. Following the war's end, Brezhnev was promoted to the party's Central Committee in 1952 and became a full member of the Politburo by 1957. In 1964, he consolidated enough power to replace Nikita Khrushchev as First Secretary of the CPSU, the most powerful position in the country.

During his tenure, Brezhnev's governance improved the Soviet Union's international standing while stabilizing the position of its ruling party at home. Whereas Khrushchev regularly enacted policies without consulting the Politburo, Brezhnev was careful to minimize dissent among the party elite by reaching decisions through consensus thereby restoring the semblance of collective leadership. Additionally, while pushing for détente between the two Cold War superpowers, he achieved nuclear parity with the United States and strengthened Moscow's dominion over Central and Eastern Europe. Furthermore, the massive arms buildup and widespread military interventionism under Brezhnev's leadership substantially expanded Soviet influence abroad, particularly in the Middle East and Africa. By the mid-1970s, numerous observers argued the Soviet Union had surpassed the United States to become the world's strongest military power.

Conversely, Brezhnev's disregard for political reform ushered in an era of socioeconomic decline referred to as the Era of Stagnation. In addition to pervasive corruption and falling economic growth, this period was characterized by an increasing technological gap between the Soviet Union and the United States.

After 1975, Brezhnev's health rapidly deteriorated and he increasingly withdrew from international affairs despite maintaining his hold on power. He died on 10 November 1982 and was succeeded as general secretary by Yuri Andropov. Upon coming to power in 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev denounced Brezhnev's government for its inefficiency and inflexibility before launching a campaign to liberalise the Soviet Union. Notwithstanding the backlash to his regime's policies in the mid-1980s, Brezhnev's rule has received consistently high approval ratings in public polls conducted in post-Soviet Russia.United Kingdom

This section is an excerpt from Harold Wilson.

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British statesman and Labour politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, from 1964 to 1970 and again from 1974 to 1976. He was Leader of the Labour Party from 1963 to 1976, Leader of the Opposition twice from 1963 to 1964 and again from 1970 to 1974, and a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1945 to 1983. Wilson is the only Labour leader to have formed administrations following four general elections.

Born in Huddersfield, Yorkshire, to a politically active middle-class family, Wilson studied a combined degree of philosophy, politics, and economics at Jesus College, Oxford. He was later an Economic History lecturer at New College, Oxford, and a research fellow at University College, Oxford. Elected to Parliament in 1945, Wilson was appointed to the Attlee government as a Parliamentary Secretary; he became Secretary for Overseas Trade in 1947, and was elevated to the Cabinet shortly thereafter as President of the Board of Trade. Following Labour's defeat at the 1955 election, Wilson joined the Shadow Cabinet as Shadow Chancellor, and was moved to the role of Shadow Foreign Secretary in 1961. When Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell died suddenly in January 1963, Wilson won the subsequent leadership election to replace him, becoming Leader of the Opposition.

Wilson led Labour to a narrow victory at the 1964 election. His first period as prime minister saw a period of low unemployment and economic prosperity; this was however hindered by significant problems with Britain's external balance of payments. His government oversaw significant societal changes, abolishing both capital punishment and theatre censorship, partially decriminalising male homosexuality in England and Wales, relaxing the divorce laws, limiting immigration, outlawing racial discrimination, and liberalising birth control and abortion law. In the midst of this programme, Wilson called a snap election in 1966, which Labour won with a much increased majority. His government armed Nigeria during the Biafran War. In 1969, he sent British troops to Northern Ireland. After losing the 1970 election to Edward Heath's Conservatives, Wilson chose to remain in the Labour leadership, and resumed the role of Leader of the Opposition for four years before leading Labour through the February 1974 election, which resulted in a hung parliament. Wilson was appointed prime minister for a second time; he called a snap election in October 1974, which gave Labour a small majority. During his second term as prime minister, Wilson oversaw the referendum that confirmed the UK's membership of the European Communities.

In March 1976, Wilson suddenly announced his resignation as prime minister. He remained in the House of Commons until retiring in 1983 when he was elevated to the House of Lords as Lord Wilson of Rievaulx. While seen by admirers as leading the Labour Party through difficult political issues with considerable skill, Wilson's reputation was low when he left office and is still disputed in historiography. Some scholars praise his unprecedented electoral success for a Labour prime minister and holistic approach to governance, while others criticise his political style and handling of economic issues. Several key issues which he faced while prime minister included the role of public ownership, whether Britain should seek the membership of the European Communities, and British involvement in the Vietnam War. His stated ambitions of substantially improving Britain's long-term economic performance, applying technology more democratically, and reducing inequality were to some extent unfulfilled.North America

United States

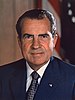

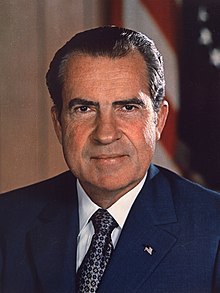

Nixon

This section is an excerpt from Presidency of Richard Nixon.

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Pre-vice presidency 36th Vice President of the United States Post-vice presidency 37th President of the United States

Judicial appointments Policies First term

Second term

Impeachment process Post-presidency

Presidential campaigns Vice presidential campaigns

|

||

Richard Nixon's tenure as the 37th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1969, and ended when he resigned on August 9, 1974, in the face of almost certain impeachment and removal from office, the only U.S. president ever to do so. He was succeeded by Gerald Ford, whom he had appointed vice president after Spiro Agnew became embroiled in a separate corruption scandal and was forced to resign. Nixon, a prominent member of the Republican Party from California who previously served as vice president for two terms under president Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 to 1961, took office following his narrow victory over Democrat incumbent vice president Hubert Humphrey and American Independent Party nominee George Wallace in the 1968 presidential election. Four years later, in the 1972 presidential election, he defeated Democrat nominee George McGovern, to win re-election in a landslide. Although he had built his reputation as a very active Republican campaigner, Nixon downplayed partisanship in his 1972 landslide re-election.

Nixon's primary focus while in office was on foreign affairs. He focused on détente with the People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union, easing Cold War tensions with both countries. As part of this policy, Nixon signed the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and SALT I, two landmark arms control treaties with the Soviet Union. Nixon promulgated the Nixon Doctrine, which called for indirect assistance by the United States rather than direct U.S. commitments as seen in the ongoing Vietnam War. After extensive negotiations with North Vietnam, Nixon withdrew the last U.S. soldiers from South Vietnam in 1973, ending the military draft that same year. To prevent the possibility of further U.S. intervention in Vietnam, Congress passed the War Powers Resolution over Nixon's veto.

In domestic affairs, Nixon advocated a policy of "New Federalism", in which federal powers and responsibilities would be shifted to state governments. However, he faced a Democratic Congress that did not share his goals and, in some cases, enacted legislation over his veto. Nixon's proposed reform of federal welfare programs did not pass Congress, but Congress did adopt one aspect of his proposal in the form of Supplemental Security Income, which provides aid to low-income individuals who are aged or disabled. The Nixon administration adopted a "low profile" on school desegregation, but the administration enforced court desegregation orders and implemented the first affirmative action plan in the United States. Nixon also presided over the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency and the passage of major environmental laws like the Clean Water Act, although that law was vetoed by Nixon and passed by override. Economically, the Nixon years saw the start of a period of "stagflation" that would continue into the 1970s.

Nixon was far ahead in the polls in the 1972 presidential election, but during the campaign, Nixon operatives conducted several illegal operations designed to undermine the opposition. They were exposed when the break-in of the Democratic National Committee Headquarters ended in the arrest of five burglars. This kicked off the Watergate Scandal and gave rise to a congressional investigation. Nixon denied any involvement in the break-in. However, after a tape emerged revealing that Nixon had known about the White House connection to the burglaries shortly after they occurred, the House of Representatives initiated impeachment proceedings. Facing removal by Congress, Nixon resigned from office.

Though some scholars believe that Nixon "has been excessively maligned for his faults and inadequately recognised for his virtues", Nixon is generally ranked as a below average president in surveys of historians and political scientists. This section is an excerpt from Watergate scandal.| Watergate scandal |

|---|

The Watergate complex in 2006 The Watergate complex in 2006 |

| Events |

| List |

| People |

| Watergate burglars |

| Groups |

| CRP |

| White House |

| Judiciary |

| Journalists |

| Intelligence community |

| Congress |

Related

|

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Pre-vice presidency 36th Vice President of the United States Post-vice presidency 37th President of the United States

Judicial appointments Policies First term

Second term

Impeachment process Post-presidency

Presidential campaigns Vice presidential campaigns

|

||

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon which began in 1972 and ultimately led to Nixon's resignation in 1974. It revolved around members of a group associated with Nixon's 1972 re-election campaign breaking into and planting listening devices in the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate Office Building in Washington, D.C., on June 17, 1972, and Nixon's later attempts to hide his administration's involvement.

Following the arrest of the burglars, both the press and the Department of Justice connected the money found on those involved to the Committee for the Re-Election of the President (CRP), the fundraising arm of Nixon's campaign. Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, journalists from The Washington Post, pursued leads provided by a source they called "Deep Throat" (later identified as Mark Felt, associate director of the FBI) and uncovered a massive campaign of political spying and sabotage directed by White House officials and illegally funded by donor contributions. Nixon dismissed the accusations as political smears, and he won the election in a landslide in November. Further investigation and revelations from the burglars' trial led the Senate to establish a special Watergate Committee and the House of Representatives to grant its Judiciary Committee expanded authority in February 1973. The burglars received lengthy prison sentences that they were told would be reduced if they co-operated, which began a flood of testimony from witnesses. In April, Nixon appeared on television to deny wrongdoing on his part and to announce the resignation of his aides. After it was revealed that Nixon had installed a voice-activated taping system in the Oval Office, his administration refused to grant investigators access to the tapes, leading to a constitutional crisis. The televised Senate Watergate hearings by this point had garnered nationwide attention and public interest.

Attorney General Elliot Richardson appointed Archibald Cox as a special prosecutor for Watergate in May. Cox obtained a subpoena for the tapes, but Nixon continued to resist. In the "Saturday Night Massacre" in October, Nixon ordered Richardson to fire Cox, after which Richardson resigned, as did his deputy William Ruckelshaus; Solicitor General Robert Bork carried out the order. The incident bolstered a growing public belief that Nixon had something to hide, but he continued to defend his innocence and said he was "not a crook". In April 1974, Cox's replacement Leon Jaworski issued a subpoena for the tapes again, but Nixon only released edited transcripts of them. In July, the Supreme Court ordered Nixon to release the tapes, and the House Judiciary Committee recommended that he be impeached for obstructing justice, abuse of power, and contempt of Congress. In one of the tapes, later known as "the smoking gun", he ordered aides to tell the FBI to halt its investigation. On the verge of being impeached, Nixon resigned the presidency on August 9, 1974, becoming the only U.S. president to do so. In all 48 people were found guilty of Watergate-related crimes, but Nixon was pardoned by his vice president and successor Gerald Ford on September 8.

Public response to the Watergate disclosures had electoral ramifications: the Republican Party lost four seats in the Senate and 48 seats in the House at the 1974 mid-term elections, and Ford's pardon of Nixon is widely agreed to have contributed to his election defeat in 1976. A word combined with the suffix "-gate" has become widely used to name scandals, even outside the U.S., and especially in politics.Carter

This section is an excerpt from Presidency of Jimmy Carter.

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

76th Governor of Georgia

39th President of the United States Policies Appointments Tenure Presidential campaigns Post-presidency

|

||

Jimmy Carter's tenure as the 39th president of the United States began with his inauguration on January 20, 1977, and ended on January 20, 1981. Carter, a Democrat from Georgia, took office following his narrow victory over Republican incumbent president Gerald Ford in the 1976 presidential election. His presidency ended following his landslide defeat in the 1980 presidential election to Republican Ronald Reagan, after one term in office. At age 100, he is the oldest living, longest-lived and longest-married president, and has the longest post-presidency. He is also the fourth-oldest living former state leader.

Carter took office during a period of "stagflation", as the economy experienced a combination of high inflation and slow economic growth. His budgetary policies centered on taming inflation by reducing deficits and government spending. Responding to energy concerns that had persisted through much of the 1970s, his administration enacted a national energy policy designed for long-term energy conservation and the development of alternative resources. In the short term, the country was beset by an energy crisis in 1979 which was overlapped by a recession in 1980. Carter sought reforms to the country's welfare, health care, and tax systems, but was largely unsuccessful, partly due to poor relations with Democrats in Congress.

Carter reoriented U.S. foreign policy towards an emphasis on human rights. He continued the conciliatory late Cold War policies of his predecessors, normalizing relations with China and pursuing further Strategic Arms Limitation Talks with the Soviet Union. In an effort to end the Arab–Israeli conflict, he helped arrange the Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt. Through the Torrijos–Carter Treaties, Carter guaranteed the eventual transfer of the Panama Canal to Panama. Denouncing the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, he reversed his conciliatory policies towards the Soviet Union and began a period of military build-up and diplomatic pressure such as pulling out of the Moscow Olympics.

The final fifteen months of Carter's presidential tenure were marked by several additional major crises, including the Iran hostage crisis and economic malaise. Ted Kennedy, a prominent liberal Democrat who protested Carter's opposition to a national health insurance system, challenged Carter in the 1980 Democratic primaries. Boosted by public support for his policies in late 1979 and early 1980, Carter rallied to defeat Kennedy and win re-nomination. He lost the 1980 presidential election in a landslide to Republican nominee Ronald Reagan. Polls of historians and political scientists generally rank Carter as a below-average president, although his post-presidential activities are viewed more favorably.South America

Oceania

Notes

- The name translates as "the warrior who goes from conquest to conquest, leaving fire in his path", "the warrior who leaves a trail of fire in his path", or "the warrior who knows no defeat because of his endurance and inflexible will and is all powerful, leaving fire in his wake as he goes from conquest to conquest".

- /ˈmaʊ (t)səˈtʊŋ/; Chinese: 毛泽东; pinyin: Máo Zédōng pronounced ; traditionally romanised as Mao Tse-tung. In this Chinese name, the family name is Mao and Ze is a generation name.

- Russian: Леонид Ильич Брежнев, IPA: [lʲɪɐˈnʲit ɨˈlʲjidʑ ˈbrʲeʐnʲɪf] ;

Ukrainian: Леонід Ілліч Брежнєв, romanized: Leonid Illich Brezhniev, IPA: [leoˈn⁽ʲ⁾id iˈl⁽ʲ⁾ːidʒ ˈbrɛʒnʲeu̯]. - Most news sources give Wilson's date of death as 24 May 1995. However, his biography on gov.uk states that he died on 23 May 1995, as does his entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, which cites his death certificate.

- Due to the early presence of US troops in Vietnam, the start date of the Vietnam War is a matter of debate. In 1998, after a high-level review by the Department of Defense (DoD) and through the efforts of Richard B. Fitzgibbon's family, the start date of the Vietnam War according to the US government was officially changed to 1 November 1955. US government reports currently cite 1 November 1955 as the commencement date of the "Vietnam Conflict", because this date marked when the US Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) in Indochina (deployed to Southeast Asia under President Truman) was reorganized into country-specific units and MAAG Vietnam was established. Other start dates include when Hanoi authorized Viet Cong forces in South Vietnam to begin a low-level insurgency in December 1956, whereas some view 26 September 1959, when the first battle occurred between the Viet Cong and the South Vietnamese army, as the start date.

- The figures of 58,220 and 303,644 for US deaths and wounded come from the Department of Defense Statistical Information Analysis Division (SIAD), Defense Manpower Data Center, as well as from a Department of Veterans fact sheet dated May 2010; the total is 153,303 WIA excluding 150,341 persons not requiring hospital care the CRS (Congressional Research Service) Report for Congress, American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics, dated 26 February 2010, and the book Crucible Vietnam: Memoir of an Infantry Lieutenant. Some other sources give different figures (e.g. the 2005/2006 documentary Heart of Darkness: The Vietnam War Chronicles 1945–1975 cited elsewhere in this article gives a figure of 58,159 US deaths, and the 2007 book Vietnam Sons gives a figure of 58,226)

References

- "Name of Technical Sergeant Richard B. Fitzgibbon to be added to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial". Department of Defense (DoD). Archived from the original on 20 October 2013.

- ^ Lawrence, A.T. (2009). Crucible Vietnam: Memoir of an Infantry Lieutenant. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-4517-2.

- Olson & Roberts 2008, p. 67.

- "Chapter 5, Origins of the Insurgency in South Vietnam, 1954–1960". The Pentagon Papers (Gravel Edition), Volume 1. Boston: Beacon Press. 1971. Section 3, pp. 314–346. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2008 – via International Relations Department, Mount Holyoke College.

- Prior to this, the Military Assistance Advisory Group, Indochina (with an authorized strength of 128 men) was set up in September 1950 with a mission to oversee the use and distribution of US military equipment by the French and their allies.

- America's Wars (PDF) (Report). Department of Veterans Affairs. May 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2014.

- Anne Leland; Mari–Jana "M-J" Oboroceanu (26 February 2010). American War and Military Operations: Casualties: Lists and Statistics (PDF) (Report). Congressional Research Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 14, 2023.

- Aaron Ulrich (editor); Edward FeuerHerd (producer and director) (2005, 2006). Heart of Darkness: The Vietnam War Chronicles 1945–1975 (DVD) (Documentary). Koch Vision. Event occurs at 321 minutes. ISBN 1-4172-2920-9. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- Falk, Richard A. (1973). "Environmental Warfare and Ecocide — Facts, Appraisal, and Proposals". Bulletin of Peace Proposals. 4 (1): 80–96. doi:10.1177/096701067300400105. ISSN 0007-5035. JSTOR 44480206. S2CID 144885326.

- Chiarini, Giovanni (1 April 2022). "Ecocide: From the Vietnam War to International Criminal Jurisdiction? Procedural Issues In-Between Environmental Science, Climate Change, and Law". Cork Online Law Review. SSRN 4072727.

- Fox, Diane N. (2003). "Chemical Politics and the Hazards of Modern Warfare: Agent Orange". In Monica, Casper (ed.). Synthetic Planet: Chemical Politics and the Hazards of Modern Life (PDF). Routledge Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-27.

- Kolko, Gabriel (1985). Anatomy of a War: Vietnam, the United States, and the Modern Historical Experience. Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-394-74761-3.

- Cite error: The named reference

Vietnam War :0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Zierler, David (2011). The invention of ecocide: agent orange, Vietnam, and the scientists who changed the way we think about the environment. Athens, Georgia: Univ. of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-3827-9.

- Kalb, Marvin (22 January 2013). "It's Called the Vietnam Syndrome, and It's Back". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on December 24, 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- Horne, Alistair (2010). Kissinger's Year: 1973. Phoenix. pp. 370–371. ISBN 978-0-7538-2700-0.

- (Hebrew: מלחמת יום הכיפורים, Milẖemet Yom HaKipurim, or מלחמת יום כיפור, Milẖemet Yom Kipur; Arabic: حرب أكتوبر, Ḥarb ʾUktōbar, or حرب تشرين, Ḥarb Tišrīn),

- Rabinovich, Abraham (2004). The Yom Kippur War: The Epic Encounter That Transformed the Middle East. Schoken Books. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-8052-1124-5.

- Herzog (1975).

- James Bean and Craig Girard (2001). "Anwar al-Sadat's grand strategy in the Yom Kippur War" (PDF). National War College. pp. 1, 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- El-Gamasy (1993). The October War: Memoirs of Field Marshal El-Gamasy of Egypt. The American University in Cairo Press. p. 181.

- Gutfeld, Arnon; Vanetik, Boaz (30 March 2016). "'A Situation That Had to Be Manipulated': The American Airlift to Israel During the Yom Kippur War". Middle Eastern Studies. 52 (3): 419–447. doi:10.1080/00263206.2016.1144393. S2CID 146890821. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- Rodman, David (29 July 2015). "The Impact of American Arms Transfers to Israel during the 1973 Yom Kippur War". Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs. 7 (3): 107–114. doi:10.1080/23739770.2013.11446570. S2CID 141596916. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- Levey, Zach (7 October 2008). "Anatomy of an airlift: United States military assistance to Israel during the 1973 war". Cold War History. 8 (4): 481–501. doi:10.1080/14682740802373552. S2CID 154204359. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- Quandt, William (2005). Peace Process: American Diplomacy and the Arab–Israeli Conflict Since 1967 (third ed.). California: University of California Press. pp. 104–105. ISBN 978-0-520-24631-7.

- Hammad (2002), pp. 237–276

- Gawrych (1996), p. 60.

- "Kissinger Gave Green Light for Israeli Offensive Violating 1973 Cease-Fire;". The National Security Archive. 17 October 2024.

- Geroux, John Spencer, Jayson (2022-01-13). "Urban Warfare Project Case Study #4: Battle of Suez City". Modern War Institute. Retrieved 2024-09-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Oil Squeeze". Time. 1979-02-05. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- Hubbert, Marion King (June 1956). Nuclear Energy and the Fossil Fuels 'Drilling and Production Practice' (PDF). Spring Meeting of the Southern District. Division of Production. American Petroleum Institute. San Antonio, Texas: Shell Development Company. pp. 22–27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-27. Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- Duncan, Richard C (November 2001). "The Peak of World Oil Production and the Road to the Olduvai Gorge". Population and Environment. 22 (5): 503–22. doi:10.1023/A:1010793021451. ISSN 1573-7810. S2CID 150522386. Archived from the original on 2009-06-24. Retrieved 2009-07-11.

- Hassler, John; Krusell, Per; Olovsson, Conny (2021). "Directed Technical Change as a Response to Natural Resource Scarcity". Journal of Political Economy. 129 (11): 3039–3072. doi:10.1086/715849. hdl:10419/215453. ISSN 0022-3808. S2CID 199428841.

- Mohammed, Mikidadu (2017). Essays on the Causes and Dynamic Effects of Oil Price Shocks. University of Utah. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Mankiw, N. Gregory; Scarth William M. (2003). Macroeconomics: Canadian Edition Updated. New York: Worth Publishers. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-7167-5928-7. Retrieved 13 November 2009.

- Rumerman, Judy. "The Boeing 747" Archived October 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission. Retrieved: 30 April 2006.

- "The Airbus A300". CBC News. 2001-11-12. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- "TriStar Flies to Moscow". Flight International. March 21, 1974. p. 358. Archived from the original on 18 June 2015.

- Smith, Hedrick (March 13, 1974). "Lockheed's Tristar Is Displayed in Soviet". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 February 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- "Russia's New Long-Hauler". Flight International. August 20, 1977. p. 524. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019.

- "Business | Airbus unveils 'superjumbo' jet". BBC News. 2005-01-18. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- "Boeing lands US$100B worth of orders for its new 777 mini-jumbo jet, its biggest combined haul ever | Financial Post". Financial Post. Business.financialpost.com. 2013-11-18. Retrieved 2014-04-27.

- Tina Fletcher-Hill (2011-11-23). "BBC Two – How to Build..., Series 2, A Super Jumbo Wing". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2014-04-27.

- Pallini, Thomas (30 July 2020). "Double-decker planes are going extinct as Airbus and Boeing discontinue their largest models. Here's why airlines are abandoning 4-engine jets". Business Insider. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- Boddy-Evans, Alistair. "Biography of Idi Amin, Brutal Dictator of Uganda". ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- Roland Anthony Oliver, Anthony Atmore (1967). "Africa Since 1800". The Geographical Journal. 133 (2): 272. Bibcode:1967GeogJ.133Q.230M. doi:10.2307/1793302. ISSN 0016-7398. JSTOR 1793302.

- Dale C. Tatum. Who influenced whom?. p. 177.

- Gareth M. Winrow. The Foreign Policy of the GDR in Africa, p. 141.

- Subramanian, Archana (6 August 2015). "Asian expulsion". The Hindu.

- "Idi Amin: A Byword for Brutality". News24. 21 July 2003. Archived from the original on 5 June 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- Gershowitz, Suzanne (20 March 2007). "The Last King of Scotland, Idi Amin, and the United Nations". Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ^ Keatley, Patrick (18 August 2003). "Idi Amin". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- "Dictator Idi Amin dies". 16 August 2003. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2020 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- Ullman, Richard H. (April 1978). "Human Rights and Economic Power: The United States Versus Idi Amin". Foreign Affairs. 56 (3): 529–543. doi:10.2307/20039917. JSTOR 20039917. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

The most conservative estimates by informed observers hold that President Idi Amin Dada and the terror squads operating under his loose direction have killed 100,000 Ugandans in the seven years he has held power.

- Crawford Young, Thomas Edwin Turner, The Rise and Decline of the Zairian State, p. 210, 1985, University of Wisconsin Press

- Vieira, Daviel Lazure: Precolonial Imaginaries and Colonial Legacies in Mobutu's "Authentic" Zaire in: Exploitation and Misrule in Colonial and Postcolonial Africa, (edited by) Kalu, Kenneth and Falola, Toyin, pp. 165–191, Palgrave Macmillan, 2019

- David F. Schmitz, The United States and Right-Wing Dictatorships, 1965–1989, pp. 9–36, 2006, Cambridge University Press

- "Mobutu Sese Seko". The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia. Columbia University Press. 2012. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- "Revealing the Ultimate 2020 List: The 10 Most Corrupt Politicians in the World - The Sina Times". 2020-01-03. Archived from the original on 3 January 2024. Retrieved 2024-01-03.

- Acemoglu, Daron; Robinson, James A. & Verdier, Thierry (April–May 2004). "Kleptocracy and Divide-and-Rule: A Model of Personal Rule". Journal of the European Economic Association. 2 (2–3): 162–192. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.687.1751. doi:10.1162/154247604323067916. S2CID 7846928. Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- Pearce, Justin (16 January 2001). "DR Congo's troubled history". BBC. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- Jung Chang and Jon Halliday, Mao: the Unknown Story, p. 574, 2006 edition, Anchor Books

- Washington Post, "Mobutu: A Rich man In Poor Standing". Archived 25 September 2022 at the Wayback Machine 2 October 1991.

- The New York Times, "Mobutu’s village basks in his glory". Archived 20 March 2024 at the Wayback Machine 29 September 1988.

- Tharoor, Ishaan (20 October 2011). "Mobutu Sese Seko". Top 15 Toppled Dictators. Time Magazine. Archived from the original on 22 October 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- "Mao Tse-tung". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- Brahma Chellaney (2006). Asian Juggernaut: The Rise of China, India, and Japan. HarperCollins. p. 195. ISBN 9788172236502.

Indeed, Beijing's acknowledgement of Indian control over Sikkim seems limited to the purpose of facilitating trade through the vertiginous Nathu-la Pass, the scene of bloody artillery duels in September 1967 when Indian troops beat back attacking Chinese forces.

- Jacobsen, K.A. (2023). Routledge Handbook of Contemporary India. Taylor & Francis. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-000-98423-1.

India emerged as the predominant regional power in South Asia after the successful vivisection of Pakistan in 1971

- Shrivastava, Sanskar (2011-10-30). "1971 India Pakistan War: Role of Russia, China, America and Britain". The World Reporter. Archived from the original on 1 November 2011. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- Mehrotra, Santosh K., ed. (1991), "Bilateral trade", India and the Soviet Union: Trade and Technology Transfer, Cambridge Russian, Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 161–206, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511559884.010, ISBN 978-0-521-36202-3, archived from the original on 18 June 2018, retrieved 2023-03-29

- ^ Bose, Sugata; Jalal, Ayesha (2024), "The Indian Emergency (1975–1977) in Historical Perspective", When Democracy Breaks, Oxford University Press, pp. 221–236, doi:10.1093/oso/9780197760789.003.0008, ISBN 978-0-19-776078-9

- Khorana, M. (1991). The Indian Subcontinent in Literature for Children and Young Adults: An Annotated Bibliography of English-language Books. Bibliographies and indexes in world literature. Greenwood Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-313-25489-5. Archived from the original on 6 October 2023. Retrieved 2023-05-13.

- Hampton, W.H.; Burnham, V.S.; Smith, J.C. (2003). The Two-Edged Sword: A Study of the Paranoid Personality in Action. Sunstone Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-86534-147-0. Archived from the original on 5 October 2023. Retrieved 2023-05-13.

- Steinberg, B.S. (2008). Women in Power: The Personalities and Leadership Styles of Indira Gandhi, Golda Meir, and Margaret Thatcher. Arts Insights Series. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-7735-7502-8. Archived from the original on 6 October 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- "BBC Indira Gandhi 'greatest woman'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- "Indira Gandhi, Amrit Kaur named by TIME among '100 Women of the Year'". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Tucker, Spencer C.; Roberts, Priscilla (2008). "Kosygin, Alexei". The Encyclopedia of the Arab-Israeli Conflict: A Political, Social, and Military History : A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1851098422.

- Zubok, Vladislav M. (2009) . A Failed Empire: The Soviet Union in the Cold War from Stalin to Gorbachev. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-8078-5958-2.

- Brown 1990, p. 184.

- McCauley, Martin (1993). The Soviet Union 1917–1991. Longman. p. 288. ISBN 0582-01323-2.

- Mendras, Marie (1989). "Policy Outside and Politics Inside". In Brown, Archie (ed.). Political Leadership in the Soviet Union. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 143. ISBN 0-253-21228-6.

- "Brezhnev". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- Jessup, John E. (11 August 1998). An Encyclopedic Dictionary of Conflict and Conflict Resolution, 1945–1996. Greenwood. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-313-28112-9.

- "Harold Wilson". Gov.uk. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- Jenkins, Roy (7 January 2016). "Wilson, (James) Harold, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/58000. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Nicholas-Thomas Symonds, Harold Wilson: The Winner (Orion Publishing Company, 2023).

- Andrew S. Crines and Kevin Hickson, eds., Harold Wilson: The Unprincipled Prime Minister?: A Reappraisal of Harold Wilson (Biteback Publishing, 2016) p. 311.

- Goodman, Geoffrey (1 July 2005). "Harold Wilson obituary". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- Ben Pimlott, Harold Wilson (1992), pp. 604–605, 648, 656, 670–677, 689.

- Aitken, p. 577.

- Rottinghaus, Brandon; Vaughn, Justin S. (19 February 2018). "How Does Trump Stack Up Against the Best — and Worst — Presidents?". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- "Siena's 6th Presidential Expert Poll 1982 – 2018". Siena College Research Institute. February 13, 2019.

- "Presidential Historians Survey 2017". C-SPAN. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- Perry, James M. "Watergate Case Study". Class Syllabus for "Critical Issues in Journalism". Columbia School of Journalism, Columbia University. Archived from the original on July 15, 2019. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- Dickinson, William B.; Cross, Mercer; Polsky, Barry (1973). Watergate: chronology of a crisis. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Inc. pp. 8, 133, 140, 180, 188. ISBN 0-87187-059-2. OCLC 20974031.

- Rybicki, Elizabeth; Greene, Michael (October 10, 2019). "The Impeachment Process in the House of Representatives". CRS Report for Congress. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress. pp. 5–7. R45769. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- "H.Res.74 – 93rd Congress, 1st Session". congress.gov. February 28, 1973. Archived from the original on December 30, 2019. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- "A burglary turns into a constitutional crisis". CNN. June 16, 2004. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2014.

- "'Gavel-to-Gavel': The Watergate Scandal and Public Television". American Archive of Public Broadcasting. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- Hamilton, Dagmar S. "The Nixon Impeachment and the Abuse of Presidential Power", In Watergate and Afterward: The Legacy of Richard M. Nixon. Leon Friedman and William F. Levantrosser, eds. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1992. ISBN 0-313-27781-8

- Smith, Ronald D. and Richter, William Lee. Fascinating People and Astounding Events From American History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 1993. ISBN 0-87436-693-3

- Lull, James and Hinerman, Stephen. Media Scandals: Morality and Desire in the Popular Culture Marketplace. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-231-11165-7

- Trahair, R.C.S. From Aristotelian to Reaganomics: A Dictionary of Eponyms With Biographies in the Social Sciences. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1994. ISBN 0-313-27961-6

- "El 'valijagate' sigue dando disgustos a Cristina Fernández | Internacional". El País. November 4, 2008. Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

Sources

- Aitken, Jonathan (1996). Nixon: A Life. Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing. ISBN 978-0-89526-720-7.

- Brown, Archie, ed. (1990). The Soviet Union: A Biographical Dictionary. London, United Kingdom: George Weidenfeld and Nicolson Ltd. ISBN 0-297-82010-9.

- Gawrych, Dr. George W. (1996). The 1973 Arab-Israeli War: The Albatross of Decisive Victory. Combat Studies Institute, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College.

- Herzog, Chaim (1975). The War of Atonement: The Inside Story of the Yom Kippur War. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-35900-9.

- Olson, James S.; Roberts, Randy (2008). Where the Domino Fell: America and Vietnam 1945–1995 (5th ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-8222-5.

| 1970s | |

|---|---|

| Culture | |

| Science and technology | |

| History | |