| Abo Formation | |

|---|---|

| Stratigraphic range: middle Wolfcampian to early Leonardian ~290–275 Ma PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N | |

Abo Formation at its type section in Abo Pass, New Mexico, USA. This is the Cañon de Espinoso Member. Abo Formation at its type section in Abo Pass, New Mexico, USA. This is the Cañon de Espinoso Member. | |

| Type | Formation |

| Unit of | Group |

| Underlies | Yeso Group |

| Overlies | Bursum Formation of the Madera Group |

| Thickness | 280 m (920 ft) at type section |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Mudstone |

| Other | Sandstone |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 34°26′13″N 106°23′38″W / 34.437°N 106.394°W / 34.437; -106.394 |

| Region | New Mexico |

| Country | United States |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Abo Canyon |

| Named by | W.T. Lee and G.H. Girty (1909) |

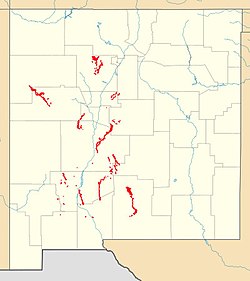

Exposures of Abo Formation in New Mexico | |

The Abo Formation is a geologic formation in New Mexico. It contains fossils characteristic of the Cisuralian epoch of the Permian period.

Description

The Abo Formation consists of fluvial redbed mudstones and sandstones, including river channel deposits in its lower beds (Scholle Member) and distinctive sandstone sheets in its upper beds (Cañon de Espinoso Member.) Its depositional environment was typical of the "wet red beds" of tropical Pangaea. It is extensively exposed in the mountains and other uplifts bordering the Rio Grande Rift, with a thickness of 280 meters (920 feet) at the type section. It is also present in the subsurface in the Raton Basin.

The base of the Abo is gradational with the Madera Group, and is usually placed at the first massive marine limestone bed below the fluvial sediments of the Abo. It is overlain by the Yeso Formation, with the base of the Yeso placed at the first massive sandstone bed showing frosted grains and other eolian features. The transition zone between the Madera Group and the Abo Formation is distinctive enough in many locations that it is broken out into its own formation, the Bursum Formation.

Sandstone in the exposures towards the north, at Abo Pass and in the Jemez Mountains, tends to be arkosic, with detrital feldspars dominated by potassium feldspar including microcline. The feldspar is locally albitized, possibly by brines in evaporite basins or due to high heat flow in the crust. Granitic rock fragments are much more common than metamorphic. Cementing is usually by calcite, but quartz cementing is often present. Carbonate grains are likely reworked caliche. The formation fines to the south. The composition and southward fining indicate a granitic source to the north.

The Abo Formation was deposited in a time of rapid global warming. Carbon and oxygen isotope ratios in caliches within the formation indicate a rise in temperature from 15-30 °C during the eighteen million years in which the formation was deposited. This was accompanied by increased aridity. Deposition took place on a low-gradient, broad, well-oxidized alluvial plain in which rivers flowed to the Hueco seaway in southern New Mexico. There are indications in the strata of strong seasonality typical of the megamonsoonal climate of early Permian Pangaea.

The Abo transitions seamlessly to the Cutler Formation in the northern Jemez Mountains. With both names deeply entrenched in the geological literature, the convention is to use the name "Cutler Formation" north of 36 degrees north latitude and "Abo Formation" south of that latitude.

Paleontological data and regional correlations suggest that the age of the Abo Formation is middle Wolfcampian to early Leonardian.

Members

The Abo Formation is divided into the lower Scholle Member and the upper Cañon de Espinoso Member.

The Scholle Member is dominated by mudstone (87% of the type section), with some trough-crossbedded, coarse-grained, conglomeratic sandstones (11% of the type section) interpreted as channel deposits. The remaining 2% is calcrete ledges. The member is 140 meters (460 feet) thick at the type section and is a slope-forming member. It reflect relatively rapid tectonic subsidence.

The Cañon de Espinoso Member is 170 meters (560 feet) thick at the type section, of which 70% is mudstone, 21% is thin ledges of laminated climbing-rippled sandstone, and 9% is siltstone beds. The sandstones form distinctive sheet-like bodies. This member was deposited as tectonic subsidence slowed, with an episodically stable base level.

Fossils

The formation is notable for its trace fossils, which include rhizoliths, arthropod feeding and locomotion traces, and tetrapod trackways. A tracksite has been identified at Abo Pass which is dominated by Amphisauropus tracks, but also shows tracks of Dromopus, Dimetropus, Batrachichnus, Hyloidichnus, Gilmoreichnus, and Varanopus. Tracks are also found in the Lucero uplift in the Cañon de Espinoso Member that include Amphisauropus, Ichniotherium, Hyloidichnus, and Dromopus.

The formation has also produced plant, bivalve, conchostracan and vertebrate fossils in locations such as the Spanish Queen mine near Jemez Springs, which date it to the Wolfcampian (lower Permian period). Plant fossils found in the Abo Formation are mostly conifers and show two distinct paleofloras. The first, associated with red siltstone, are of low diversity and are dominated either by conifers or the peltasterm Supaia. The second paleoflora is characteristic of green shale and siltstone and is more diverse, with a variety of wetland plants, though still dominated by conifers.

One green shale site in the Caballo Mountains, interpreted as an estuarine facies of the Abo Formation, contains gastropods and diverse bivalves, including euryhaline pectins and myalinids. The Scholle Member yields most of the vertebrate fossils of the Abo Formation, typically a pelycosaur-dominated assemblage that includes lungfishes, palaeoniscoids, temnospondyl and lepospondyl amphibians, and diadectomorphs.

A bed of the formation northeast of Soccoro has the rare pseudofossil Astropolithon. This is not actually a product of living organisms, but is an unusual sedimentary structure formed by outgassing from sediments bound together by microbial mats.

Economic geology

The Abo Formation was mined for copper at the Spanish Queen Mine in the Jemez Springs area. The ore was discovered in 1575, but production had ceased by 1940. Copper was also mined in the Scholle district, particularly from the Abo and Copper Girl mines, beginning likely in the Spanish era, ca. 1629. Modern prospectors rediscovered the deposits in 1902 and mining from 1915 to 1961 produced about a quarter million dollars of copper and other metals. Remaining copper deposits in the Abo are uneconomical to mine at 2015 prices. Copper deposits in the Abo are characterized as stratabound sedimentary-copper deposit, largely taking the form of copper oxides, chalcopyrite, and chalcocite. They were likely produced when oxidizing waters enriched in chloride and carbonate from Paleozoic beds leached copper from Proterozoic source rock, then precipitated the copper in more reduced aquifers containing hydrogen sulfide.

Carbon dioxide was produced from subsurface Abo Formation beds in the Des Moines, New Mexico field from 1952 to 1966. Isotope studies suggest the carbon dioxide originated in the Earth's mantle and the Abo Formation is merely a reservoir rock.

History of investigation

The formation was first designated as the Abo sandstone of the Manzano Group by W.T. Lee and G.H Girty in 1909, who named it for Abo Canyon in the southern Manzano Mountains. In 1943, C.E. Needham and R.L. Bates defined a type section that excluded the basal marine limestone beds, and, finding that the unit was more shale than sandstone, redesignated it the Abo Formation.

In 1946, R.H. Wiltpolt and coinvestigators removed the upper eolian sandstone beds from the Abo Formation, reassigning them to the Meseta Blanca sandstone member of the Yeso Formation.

In 2005, Spencer G. Lucas and coinvestigators divided the Abo into two members, the lower Scholle Member and the upper Cañon de Espinoso Member.

See also

Footnotes

- Myers 1972.

- ^ Lucas et al. 2013.

- ^ Broadhead 2019.

- Kues & Giles 2004, pp. 98–100.

- Bonar, Hampton & Mack 2020.

- Mack & Cole 1991.

- Wood & Northrop 1946.

- Lucas et al. 2016.

- Lucas, Lerner & Haubold 2001.

- Voigt & Lucas 2016.

- Hunt & Lucas 1996.

- Lucas & Lerner 2017.

- Western Mining History 2021.

- McLemore 2016.

- Lee & Girty 1909.

- Needham & Bates 1943.

- Wilpolt et al. 1946.

- Lucas, Krainer & Colpitts 2005.

References

- Bonar, Alicia L.; Hampton, Brian A.; Mack, Greg H. (2020). "A comparison of sandstone modal composition trends from early Permian (Wolfcampian) strata of the Abo Formation in the Zuni and Manzano Mountains with age-equivalent strata throughout New Mexico" (PDF). New Mexico Geological Society Special Publication. 14: 111–122. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- Broadhead, Ronald F. (2019). "Carbon Dioxide in the Subsurface of Northeastern New Mexico" (PDF). New Mexico Geological Society Field Conference Series. 70: 101–108. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- Hunt, Adrian P.; Lucas, Spencer G. (1996). "Late Paleozoic fossil vertebrates from the Spanish Queen mine locality and vicinity, Sandoval County, New Mexico". New Mexico Geological Society Fall Field Guidebooks. 47: 22.

- Kues, B.S.; Giles, K.A. (2004). "The late Paleozoic Ancestral Rocky Mountain system in New Mexico". In Mack, G.H.; Giles, K.A. (eds.). The geology of New Mexico. A geologic history: New Mexico Geological Society Special Volume 11. pp. 5–136. ISBN 9781585460106.

- Lee, Willis T.; Girty, George H. (1909). "The Manzano Group of the Rio Grande Valley, New Mexico". United States Geological Survey Bulletin. 389. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- Lucas, S.G.; Krainer, K.; Colpitts, R.M. Jr. (2005). "Abo-Yeso (Lower Permian) stratigraphy in central New Mexico". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 31: 101–117. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- Lucas, Spencer G.; Krainer, Karl; Chaney, Dan S.; DiMichele, William A.; Voigt, Sebastian; Berman, David S.; Henrici, Amy C. (2013). "The Lower Permian Abo Formation in Central New Mexico". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 59: 161–180. hdl:10088/20977.

- Lucas, Spencer G.; Krainer, Karl; Oviatt, Charles G.; Vachard, Daniel; Berman, David S.; Henrici, Amy C. (2016). "The Permian system at Abo Pass, Central New Mexico (USA)" (PDF). New Mexico Geological Society Field Conference Series. 67: 313–350. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- Lucas, Spencer G.; Lerner, Allan J.; Haubold, Hartmut (2001). "First record of Amphisauropus and Varanopus in the Lower Permian Abo Formation, central New Mexico". Hallesches Jahrb. Geowiss B. 29: 69–78. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.503.8731.

- Lucas, Spencer G.; Lerner, Allan J. (2017). "Gallery of Geology: The rare and unusual pseudofossil Astropolithon from the Lower Permian Abo Formation near Socorro, New Mexico" (PDF). New Mexico Geology. 39 (2): 40–42. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- Mack, Greg H.; Cole, David R. (1991). "Paleoclimatic Controls on Stable Oxygen and Carbon Isotopes in Caliche of the Abo Formation (Permian), South-Central New Mexico, U.S.A.". SEPM Journal of Sedimentary Research. 61. doi:10.1306/D426773A-2B26-11D7-8648000102C1865D.

- McLemore, Virginia T. (2016). "Geology and mineral deposits of the sedimentary-copper deposits in the Scholle Mining District, Socorro, Torrance and Valencia counties, New Mexico" (PDF). New Mexico Geological Society Field Conference Series. 67: 249–254. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- Myers, Donald A. (1972). "The upper Paleozoic Madera Group in the Manzano Mountains, New Mexico" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin. 1372: F11. doi:10.3133/B1372F. ISSN 8755-531X. Wikidata Q61461236.

- Needham, C.E.; Bates, R.L. (1943). "Permian type sections in central New Mexico". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 54 (11) (published 1 November 1943): 1653–1668. Bibcode:1943GSAB...54.1653N. doi:10.1130/GSAB-54-1653. ISSN 0016-7606. Wikidata Q61031648.

- Voigt, Sebastian; Lucas, Spencer G. (2016). "Permian tetrapod footprints from the Lucero Uplift, central New Mexico" (PDF). New Mexico Geological Society Field Conference Series. 67: 387–395. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "Spanish Queen". Western Mining History Database. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- Willis Thomas Lee; George H. Girty (1909). "The Manzano group of the Rio Grande valley, New Mexico" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin. 389: 1–40. doi:10.3133/B389. ISSN 8755-531X. Wikidata Q61463147.

- Wilpolt, R.H.; MacAlpin, A.J.; Bates, R.L.; Vorbe, G. (1946). "Geologic map and stratigraphic sections of Paleozoic rocks of Joyita Hills, Los Piños Mountains, and northern Chupadera Mesa, Valencia, Torrance, and Socorro Counties, New Mexico". U.S. Geological Survey Oil and Gas Investigations Preliminary Map. 61.

- Wood, G.H.; Northrop, S.A. (1946). "Geology of the Nacimiento Mountains, San Pedro Mountain, and adjacent plateaus in parts of Sandoval and Rio Arriba Counties, New Mexico". Oil and Gas Investigations Map. 57. doi:10.3133/OM57. Wikidata Q62639452.