| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name 3-Oxobutanoic acid | |

| Systematic IUPAC name 3-Oxobutyric acid | |

| Other names

Acetoacetic acid Diacetic acid Acetylacetic acid Acetonecarboxylic acid | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| KEGG | |

| PubChem CID | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

InChI

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C4H6O3 |

| Molar mass | 102.089 g·mol |

| Appearance | Colorless, oily liquid |

| Melting point | 36.5 °C (97.7 °F; 309.6 K) |

| Boiling point | Decomposes |

| Solubility in water | Soluble |

| Solubility in organic solvents | Soluble in ethanol, ether |

| Acidity (pKa) | 3.58 |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C , 100 kPa).

| |

Acetoacetic acid (IUPAC name: 3-Oxobutanoic acid, also known as Acetonecarboxylic acid or Diacetic acid) is the organic compound with the formula CH3COCH2COOH. It is the simplest beta-keto acid, and like other members of this class, it is unstable. The methyl and ethyl esters, which are quite stable, are produced on a large scale industrially as precursors to dyes. Acetoacetic acid is a weak acid.

Biochemistry

Under typical physiological conditions, acetoacetic acid exists as its conjugate base, acetoacetate:

- AcCH2CO2H → AcCH2CO−2 + H

Unbound acetoacetate is primarily produced by liver mitochondria from its thioester with coenzyme A (CoA):

- AcCH2C(O)−CoA + OH → AcCH2CO−2 + H−CoA

The acetoacetate-CoA itself is formed by three routes:

- 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA releases acetyl CoA and acetoacetate:

- O2CCH2−C(Me)(OH)−CH2C(O)−CoA → O2CCH2−Ac + Ac−CoA

- Acetoacetyl-CoA can come from beta oxidation of butyryl-CoA:

- Et−CH2C(O)−CoA + 2NAD + H2O + FAD → Ac−CH2C(O)−CoA + 2NADH + FADH2

- Condensation of pair of acetyl CoA molecules as catalyzed by thiolase.

- 2Ac−CoA → AcCH2C(O)−CoA + H−CoA

In mammals, acetoacetate produced in the liver (along with the other two "ketone bodies") is released into the bloodstream as an energy source during periods of fasting, exercise, or as a result of type 1 diabetes mellitus. First, a CoA group is enzymatically transferred to it from succinyl CoA, converting it back to acetoacetyl CoA; this is then broken into two acetyl CoA molecules by thiolase, and these then enter the citric acid cycle. Heart muscle and renal cortex prefer acetoacetate over glucose. The brain uses acetoacetate when glucose levels are low due to fasting or diabetes.

Synthesis and properties

Acetoacetic acid may be prepared by the hydrolysis of diketene. Its esters are produced analogously via reactions between diketene and alcohols, and acetoacetic acid can be prepared by the hydrolysis of these species. In general, acetoacetic acid is generated at 0 °C and used in situ immediately.

It decomposes at a moderate reaction rate into acetone and carbon dioxide:

- CH3C(O)CH2CO2H → CH3C(O)CH3 + CO2

The acid form has a half-life of 140 minutes at 37 °C in water, whereas the basic form (the anion) has a half-life of 130 hours. That is, it reacts about 55 times more slowly. The corresponding decarboxylation of trifluoroacetoacetate is used to prepare trifluoroacetone:

- CF3C(O)CH2CO2H → CF3C(O)CH3 + CO2

It is a weak acid (like most alkyl carboxylic acids), with a pKa of 3.58.

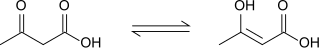

Acetoacetic acid displays keto-enol tautomerisation, with the enol form being partially stabilised by extended conjugation and intramolecular H-bonding. The equilibrium is strongly solvent depended; with the keto form dominating in polar solvents (98% in water) and the enol form accounting for 25-49% of material in non-polar solvents.

Applications

Acetoacetic esters are used for the acetoacetylation reaction, which is widely used in the production of arylide yellows and diarylide dyes. Although the esters can be used in this reaction, diketene also reacts with alcohols and amines to the corresponding acetoacetic acid derivatives in a process called acetoacetylation. An example is the reaction with 4-aminoindane:

Detection

Acetoacetic acid is measured in the urine of people with diabetes to test for ketoacidosis and for monitoring people on a ketogenic or low-carbohydrate diet. This is done using dipsticks coated in nitroprusside or similar reagents. Nitroprusside changes from pink to purple in the presence of acetoacetate, the conjugate base of acetoacetic acid, and the colour change is graded by eye. The test does not measure β-hydroxybutyrate, the most abundant ketone in the body; during treatment of ketoacidosis β-hydroxybutyrate is converted to acetoacetate so the test is not useful after treatment begins and may be falsely low at diagnosis.

Similar tests are used in dairy cows to test for ketosis.

See also

References

- "Front Matter". Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. p. 748. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- Dawson, R. M. C., et al., Data for Biochemical Research, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1959.

- ^ Franz Dietrich Klingler; Wolfgang Ebertz (2005). "Oxocarboxylic Acids". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a18_313. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Lubert Stryer (1981). Biochemistry (2nd ed.).

- Stryer, Lubert (1995). Biochemistry (Fourth ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. pp. 510–515, 581–613, 775–778. ISBN 0-7167-2009-4.

- Robert C. Krueger (1952). "Crystalline Acetoacetic Acid". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 74 (21): 5536. doi:10.1021/ja01141a521.

- Reynolds, George A.; VanAllan, J. A. (1952). "Methylglyoxal-ω-Phenylhydrazone". Organic Syntheses. 32: 84. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.032.0084; Collected Volumes, vol. 4, p. 633.

- Hay, R. W.; Bond, M. A. (1967). "Kinetics of decarboxilation of acetoacetic acid". Aust. J. Chem. 20 (9): 1823–8. doi:10.1071/CH9671823.

- Grande, Karen D.; Rosenfeld, Stuart M. (1980). "Tautomeric equilibriums in acetoacetic acid". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 45 (9): 1626–1628. doi:10.1021/jo01297a017. ISSN 0022-3263.

- Kiran Kumar Solingapuram Sai; Thomas M. Gilbert; Douglas A. Klumpp (2007). "Knorr Cyclizations and Distonic Superelectrophiles". J. Org. Chem. 72 (25): 9761–9764. doi:10.1021/jo7013092. PMID 17999519.

- ^ Nyenwe, EA; Kitabchi, AE (April 2016). "The evolution of diabetic ketoacidosis: An update of its etiology, pathogenesis and management". Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental. 65 (4): 507–21. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2015.12.007. PMID 26975543.

- Hartman, AL; Vining, EP (January 2007). "Clinical aspects of the ketogenic diet". Epilepsia. 48 (1): 31–42. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.00914.x. PMID 17241206. S2CID 21195842.

- Sumithran, Priya; Proietto, Joseph (2008). "Ketogenic diets for weight loss: A review of their principles, safety and efficacy". Obesity Research & Clinical Practice. 2 (1): I–II. doi:10.1016/j.orcp.2007.11.003. PMID 24351673.

- Misra, S; Oliver, NS (28 October 2015). "Diabetic ketoacidosis in adults" (PDF). BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 351: h5660. doi:10.1136/bmj.h5660. hdl:10044/1/41091. PMID 26510442. S2CID 2819002.

- Tatone, EH; Gordon, JL; Hubbs, J; LeBlanc, SJ; DeVries, TJ; Duffield, TF (1 August 2016). "A systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of point-of-care tests for the detection of hyperketonemia in dairy cows". Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 130: 18–32. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2016.06.002. PMID 27435643.

| Cholesterol and steroid metabolic intermediates | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mevalonate pathway |

| ||||||||||

| Non-mevalonate pathway | |||||||||||

| To Cholesterol | |||||||||||

| From Cholesterol to Steroid hormones |

| ||||||||||

| Nonhuman |

| ||||||||||