An aerial torpedo (also known as an airborne torpedo or air-dropped torpedo) is a torpedo launched from a torpedo bomber aircraft into the water, after which the weapon propels itself to the target.

First used in World War I, air-dropped torpedoes were used extensively in World War II, and remain in limited use. Aerial torpedoes are generally smaller and lighter than submarine- and surface-launched torpedoes.

History

Origins

The idea of dropping lightweight torpedoes from aircraft was conceived in the early 1910s by Bradley A. Fiske, an officer in the United States Navy. A patent for this was awarded in 1912. Fiske worked out the mechanics of carrying and releasing the aerial torpedo from a bomber, and defined tactics that included a night-time approach so that the target ship would be less able to defend itself. Fiske imagined the notional torpedo bomber would descend rapidly in a sharp spiral to evade enemy guns, then at an altitude of about 10 to 20 feet (3 to 6 m) would level off long enough to line up with the torpedo's intended path. The aircraft would release the torpedo at a distance of 1,500 to 2,000 yards (1,400 to 1,800 m) from the target. In 1915, Fiske proposed attacking enemy fleets within their own harbors using this method, if there was enough water (depth and expanse) for the torpedo to run. However, the United States Congress appropriated no funds for aerial torpedo research until 1917 when the U.S. entered into direct action in World War I. The U.S. would not have special-purpose torpedo planes until 1921.

First torpedo aircraft

Meanwhile, the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) began actively experimenting with this possibility. The first successful aerial torpedo drop was unofficially performed by the later RFC pilot Charles Gordon Bell on 27 July 1914 - dropping a Whitehead torpedo from a Short S.64 seaplane. Gordon Bell was followed the next day by RNAS pilot Arthur Longmore, when officially testing an aerial torpedo. The success of these experiments led to the construction of the first purpose-built operational torpedo aircraft, the Short Type 184, built from 1915.

An order for ten aircraft was placed, and 936 aircraft were built by ten different British aircraft companies during the First World War. The two prototype aircraft were embarked upon HMS Ben-my-Chree, which sailed for the Aegean on 21 March 1915 to take part in the Gallipoli campaign.

Around the same time of the Royal Navy experiments, in Italy Captain Alessandro Guidoni of the Regia Marina was conducting similar trials since 1913, with the help of inventor Raúl Pateras Pescara, and in February 1914 successfully dropped an 800 lb torpedo, leading to disputes over which country first used an aerial torpedo.

First World War

In November 1914, Germans were reportedly experimenting at Lake Constance with the tactic of dropping torpedoes from a Zeppelin. In December 1914, Squadron Commander Cecil L'Estrange Malone commented following his participation in the Cuxhaven Raid that "One can well imagine what might have been done had our seaplanes, or those which were sent out to attack us, carried torpedoes or light guns."

On 12 August 1915 a Short Type 184, piloted by Flight Commander Charles Edmonds, was the first aircraft in the world to attack an enemy ship with an air-launched torpedo. Operating from HMS Ben-my-Chree in the Aegean Sea, Edmonds took off with a 14-inch-diameter (360 mm), 810-pound (370 kg) torpedo to fly over land and sank a Turkish supply ship in the Sea of Marmara.

Five days later, a Turkish steamship was sunk by a torpedo aimed again by Edmonds. His formation mate, Flight Lieutenant G. B. Dacre, sank a Turkish tugboat after being forced to land on the water with engine trouble. Dacre taxied toward the tugboat, released his torpedo and was then able to take off and return to Ben-My-Chree. A limitation to using the Short more widely as a torpedo bomber was that it could only take off carrying a torpedo in conditions of perfect flying weather and calm seas, and, with that load, could only fly for a little more than 45 minutes before running out of fuel.

On May 1, 1917, a German seaplane loosed a torpedo and sank the 2,784-long-ton (2,829 t) British steamship Gena off Suffolk. A second German seaplane was downed by gunfire from the sinking Gena. German torpedo bomber squadrons were subsequently assembled at Ostend and Zeebrugge for further action in the North Sea. Later in 1917, the U.S. Navy began to perform trials using a 400-pound (180 kg) dummy torpedo that, in the first test, porpoised from the water back into the air and almost hit the aircraft that dropped it. Several British torpedo bombers were built, including the Sopwith Cuckoo, the Short Shirl and the Blackburn Blackburd, but a squadron was assembled so late in the war that it achieved no successes.

Interwar years

The United States bought its first 10 torpedo bombers in 1921, variants of the Martin MB-1. The squadron of U.S. Navy and Marine fliers was based at Naval Weapons Station Yorktown. General Billy Mitchell suggested arming the torpedo bombers with live warheads as part of Project B (the anti-ship bombing demonstration) but the Navy was only curious about aerial bomb damage effects. Instead, a trial using dummy heads on the torpedoes was carried out against a foursome of battleships steaming at 17 knots. The torpedo bombers scored well.

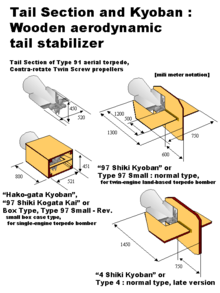

In 1931, the Japanese Navy developed the Type 91 torpedo, intended for a torpedo bomber to drop from a height of 330 feet (100 m) and a speed of 100 knots (190 km/h; 120 mph). In 1936, the torpedo was given wooden attachments to the tail, nicknamed the Kyoban, to increase its aerodynamic qualities—these attachments were shed upon hitting the water. By 1937, with the addition of a breakaway wooden damper at the nose, the torpedo could be dropped from 660 feet (200 m) and a speed of 120 knots (220 km/h; 140 mph). Tactical doctrine determined in 1938 that the Type 91 aerial torpedo should be released at a distance of 3,300 feet (1,000 m) from the target. As well, the Japanese Navy developed night attack and massed day attack doctrine, and coordinated aerial torpedo attacks between land- and carrier-based torpedo bombers.

The Japanese divided their bomber squadrons into two groups so they could attack an enemy battleship from both frontal quarters and make it difficult for the target to avoid the torpedoes by maneuvering, and more difficult for it to direct anti-aircraft fire at the bombers. Even so, Japanese tactical experts predicted that, against a battleship, the attacking force would score hits at only one-third the rate achieved during peacetime exercises.

Beginning in 1925, the United States began designing a special torpedo for purely aerial operations. The project was discontinued and revived several times, and finally resulted in the Mark 13 torpedo, which went into service in 1935. The Mark 13 differed from aerial torpedoes used by other nations in that it was wider and shorter. It was slower than its competitors but it had longer range. The weapon was released by an aircraft traveling lower and slower (50 feet (15 m) high, 110 knots (200 km/h; 130 mph) than its Japanese contemporary.

World War II

On the night of November 11–12, 1940, Fairey Swordfish biplane torpedo bombers of the British Fleet Air Arm sank three Italian battleships at the Battle of Taranto using a combination of torpedoes and bombs. In the course of the chase of the German battleship Bismarck, torpedo strikes were attempted in very bad seas, and one of these damaged her rudder allowing the British fleet to catch her. The standard British airborne torpedo for the first half of World War II was the 18-inch Mark XII, a 450 mm-diameter design weighing 1,548 lb (702 kg) with an explosive charge of 388 lb (176 kg) of trinitrotoluene (TNT).

German aerial torpedo development lagged behind other belligerents—a continuation of neglect of the category during the 1930s. At the beginning of World War II, Germany was making only five aerial torpedoes per month, and half were failing in air-drop exercises. Instead, Italian aerial torpedoes made by Fiume were purchased, with 1,000 eventually delivered.

In August 1941, Japanese aviators were practicing dropping torpedoes in the shallow waters of Kagoshima Bay, testing improvements in the Type 91 torpedo and developing tactics for the attack of ships in harbor. They discovered that the Nakajima B5N torpedo bomber could fly 160 knots (296 km/h; 184 mph), somewhat faster than expected, without the torpedoes striking the bottom of the bay 100 feet (30 m) down. On December 7, 1941, the leading wave—40 B5Ns—used the tactic to score more than 15 hits during the attack on Pearl Harbor. In April 1942, Adolf Hitler made the production of aerial torpedoes a German priority, and the Luftwaffe took the task over from the Kriegsmarine. The quantity of available aerial torpedoes outstripped usage within a year, and an excess of aerial torpedoes was on hand at the end of the war. From 1942 to late 1944, about 4,000 aerial torpedoes were used, but some 10,000 were manufactured during the whole war. Torpedo bombers were modified Heinkel He 111 and Junkers Ju 88 aircraft, but the Focke-Wulf Fw 190 fighter aircraft was successfully tested as a delivery system. Deficiencies in German-designed torpedoes after the capitulation of Italy in September 1943 were addressed just over a year before, through the yanagi visit of Japanese submarine I-30 in August 1942, to supply the Wehrmacht with the Type 91 torpedo's technology and blueprints, to be made in Germany itself as the Lufttorpedo LT 850.

The Mark 13 torpedo was the main American aerial torpedo, yet it was not perfected until after 1943 when tests showed that it failed in 70 percent of the drops made from aircraft traveling faster than 150 knots (280 km/h; 170 mph). Like the Japanese Type 91, the Mark 13 was subsequently fitted with a wooden nose covering and a wooden tail ring, both of which sheared off when it struck the water. The wooden shrouds slowed it and helped it retain its targeting direction through the duration of the air drop. The nose covering absorbed enough of the kinetic energy from the torpedo hitting the water that recommended aircraft height and speed were greatly increased to 2,400 feet (732 m) high at 410 knots (760 km/h; 470 mph).

In 1941, development began in the United States on the FIDO, an electric-powered air-dropped acoustic homing torpedo intended for anti-submarine use. In the United Kingdom, the standard airborne torpedo was strengthened for higher aircraft speeds to become the Mark XV, followed by the Mark XVII. For carrier aircraft, the explosive charge remained 388 lb (176 kg) of TNT until later in the war when it was increased to 432.5 lb (196.2 kg) of the more powerful Torpex.

During World War II, U.S. carrier-based torpedo bombers made 1,287 attacks against ships, 65% against warships, and scored hits 40% of the time. However, the low, slow approach required for torpedo bombing made the bombers easy targets for defended ships; during the Battle of Midway, for example, virtually all of the American torpedo bombers—nearly all of the obsolescent Douglas Devastator design—were shot down by the Japanese.

Korean War

After World War II, anti-aircraft defenses were sufficiently improved to render aerial torpedo attacks suicidal. Lightweight aerial torpedoes were disposed or adapted to small attack boat usage. The only significant employment of aerial torpedoes was in anti-submarine warfare.

During the Korean War the United States Navy successfully disabled the Hwacheon Dam with aerial torpedoes launched from A-1 Skyraiders.

Modern weapons

Since the advent of practical anti-ship missile technology, pioneered in World War II with the MCLOS-guided Fritz X as early as 1943, aerial torpedoes have largely been reduced to use in anti-submarine warfare. Missiles are generally much faster, with longer range, and without the same launch altitude limitation of aerial torpedoes. Some modern aerial anti-submarine torpedoes do have the necessary guidance capability to engage surface vessels, though given the widespread availability of missiles on aircraft and the small, specialized warhead on anti-submarine aerial torpedoes, this is not an option normally considered.

At the peak of the Falklands War, the Argentine Air Force, in collaboration with the Navy, outfitted an FMA IA 58 Pucará prototype, AX-04, with pylons to mount Mark 13 torpedoes. The aim was the possible production of Pucaras as torpedo-carrying aircraft to enhance the anti-ship capabilities of the Argentine air forces. Several trials were performed off Puerto Madryn, but the war was over before the technicians could evaluate the feasibility of the project.

As a result of the loss of the role of anti-shipping aerial torpedoes in modern naval doctrine, true torpedo bomber units no longer exist in modern armed forces. The most common platform for aerial torpedoes today is the ship-borne anti-submarine helicopter, followed by fixed-wing anti-submarine aircraft such as the American P-3 Orion.

The caveat to the above are torpedoes delivered by missiles/rocket systems, designed for anti-submarine warfare. Some designs are a straightforward mating of a rocket-propulsion system to the torpedo with a purely ballistic attack profile, such as the American ASROC. More complex, aerial drone-based system with autopilot have also been deployed, such as the Australian Ikara. Most such systems are designed to deploy from surface ships, though exceptions exist such as the Soviet navy RPK-2 Viyuga, which can be launched from both surface ships and submarines.

Given the relatively soft nature of submarines, modern anti-submarine aerial torpedoes are much smaller than anti-ship aerial torpedoes of the past, and often classified as light weight torpedoes. They are also often of cross-platform design, able to deploy from both aircraft and surface ships. Examples include the American Mark 46, Mark 50 and Mark 54 torpedoes. There are few if any aerial torpedo designs that are also used by submarines, owing to the significantly reduced capability of aerial torpedoes compared with their full-sized submarine counterparts such as the American Mark 48 torpedo.

Design

A successful aerial launched torpedo design needs to account for:

- The distance it travels through the air before entering the water

- The heavy impact with the water

The Japanese Type 91 torpedo used Kyoban aerodynamic tail stabilizers in the air. These stabilizers (introduced in 1936) were shed off when it entered the water. And a new control system (introduced in 1941) stabilized the rolling motion by countersteering both in the air and the water. The Type 91 torpedo could be released at speed of 180 knots (333 km/h) from 20 m (66 ft) into shallow water but also at 204 knots (the Nakajima B5N2's maximum speed) into choppy waves of a rather heavy sea.

See also

Notes

- Hughes, 2000, p. 162.

- Dictionary.com aerial torpedo. Retrieved on September 24, 2009.

- ^ Hopkins, Albert Allis. The Scientific American War Book: The Mechanism and Technique of War, Chapter XLV: Aerial Torpedoes and Torpedo Mines. Munn & Company, Incorporated, 1915

- US patent 1032394, Bradley A. Fiske, "Method of and apparatus for delivering submarine torpedoes from airships", issued 1912-07-16

- ^ Hart, Albert Bushnell. Harper's pictorial library of the world war, Volume 4. Harper, 1920, p. 335.

- The New York Times, July 23, 1915. "Torpedo Boat That Flies. Admiral Fiske Invents a Craft to Attack Fleets in Harbors" Retrieved on September 29, 2009.

- "The News of the Week: Aero Club of America Honors Admiral Fiske, Inventor of Torpedo Plane". Aerial Age Weekly. 9: 1045. August 18, 1919.

- Coletta, Paolo Enrico (1979). Admiral Bradley A. Fiske and the American Navy. Regents Press of Kansas. pp. 187–191. ISBN 9780700601813.

- Norman Polmar (2008). Aircraft Carriers: A History of Carrier Aviation and Its Influence on World Events, Volume II: 1946–2006. Potomac Books, Inc. p. 16. ISBN 9781574886658.

- ^ GlobalSecurity.org. Military. TB Torpedo Bomber. T Torpedo and bombing. Retrieved on September 29, 2009.

- C. H. Barnes (1967). Shorts Aircraft Since 1900. London: Putnam. p. 113.

- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (1996). The European powers in the First World War : an encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 378. ISBN 9781135507015.

- Mattioli, Marco (2014). Savoia-Marchetti S.79 Sparviero Torpedo-Bomber Units. Osprey. p. 6. ISBN 9781782008095.

- Ash, Eric (1999). Sir Frederick Sykes and the air revolution, 1912-1918. London: Frank Cass. p. 90. ISBN 9781136315169.

- The Stansead Journal, February 14, 1915. "Now Aerial Torpedo: Deadly Weapon Offered Navy Department." Retrieved on September 29, 2009.

- Park Benjamin (Nov 2, 1914). "The flying-fish torpedo". The Independent. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- Gardiner, Ian. The Flatpack Bombers: The Royal Navy and the Zeppelin Menace, Pen and Sword, 2009. ISBN 1-84884-071-3

- Guinness Book of Air Facts and Feats (3rd ed.). 1977.

The first air attack using a torpedo dropped by an aeroplane was carried out by Flight Commander Charles H. K. Edmonds, flying a Short 184 seaplane from Ben-my-Chree on 12 August 1915, against a 5,000 ton Turkish supply ship in the Sea of Marmara. Although the enemy ship was hit and sunk, the captain of a British submarine claimed to have fired a torpedo simultaneously and sunk the ship. It was further stated that the British submarine E14 had attacked and immobilised the ship four days earlier.

- Bruce, J.M. "The Short Seaplanes: Historic Military Aircraft No. 14: Part 3". Flight, 28 December 1956, p. 1000

- ^ Spaight, J. M. Air Power in the Next War, pp. 25–27. London, Geoffrey Bles, 1938.

- Johnson, Vice Admiral Alfred W., Retired. (1959) The Naval Bombing Experiments, Off the Virginia Capes, June and July 1921. Archived 2012-08-15 at the Wayback Machine Navy Department Library.

- ^ Peattie, 2007, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Navweaps.com. United States of America: Torpedoes of World War II. 22.4" (56.9 cm) Mark 13. Retrieved on September 29, 2009.

- ^ Campbell, 2002, p. 87.

- ^ Campbell, 2002, pp. 260–262.

- "Submarine I-30: Tabular Record of Movement". combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- Blair, Clay, Jr., Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1975, p.238.

- ^ Zabecki, David T. World War II in Europe: an encyclopedia, Part 740, Volume 2, p. 1123. Taylor & Francis, 1998. ISBN 0-8240-7029-1

- Faltum, Andrew (1996). The Essex Aircraft Carriers. Baltimore, Maryland: The Nautical & Aviation Publishing Company of America. pp. 125–126. ISBN 1-877853-26-7.

- Halbritter, Francisco (2004). Historia de la industria aeronáutica argentina. Volume 1. Asociación Amigos de la Biblioteca Nacional de Aeronáutica, 2004. ISBN 987-20774-4-4. (in Spanish)

References

- Blair, Clay. Silent Victory. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1975.

- Campbell, N. J. M.; John Campbell. Naval Weapons of World War Two. Naval Institute Press, 1986. ISBN 0-87021-459-4

- Emmott, Norman W. "Airborne Torpedoes". United States Naval Institute Proceedings, August 1977.

- Hughes, Wayne P. Fleet Tactics and Coastal Combat, Volume 167. Naval Institute Press, 2000. ISBN 1-55750-392-3

- Milford, Frederick J. "U.S. Navy Torpedoes: Part One—Torpedoes through the Thirties". The Submarine Review, April 1996. (quarterly publication of the Naval Submarine League, P.O. Box 1146, Annandale, VA 22003)

- Milford, Frederick J. "U.S. Navy Torpedoes: Part Two—The Great Torpedo Scandal, 1941–43". The Submarine Review, October 1996.

- Milford, Frederick J. "U.S. Navy Torpedoes: Part Three—WW II development of conventional torpedoes 1940–1946". The Submarine Review, January 1997.

- Peattie, Mark R. Sunburst: The Rise of Japanese Naval Air Power, 1909–1941, Naval Institute Press, 2007. ISBN 1-59114-664-X

- Thiele, Harold. Luftwaffe aerial torpedo aircraft & operations in World War Two. Hikoki, 2005. ISBN 1-902109-42-2