Mexico City, the financial center of Mexico Mexico City, the financial center of Mexico | |

| Currency | Mexican peso (MXN, Mex$) |

|---|---|

| Fiscal year | calendar year |

| Trade organizations | G20, APEC, CPTPP, USMCA, OECD and WTO |

| Country group | |

| Statistics | |

| Population | |

| GDP |

|

| GDP rank | |

| GDP growth |

|

| GDP per capita |

|

| GDP per capita rank | |

| GDP by sector |

|

| Inflation (CPI) | |

| Population below poverty line |

|

| Gini coefficient | |

| Human Development Index |

|

| Labor force |

|

| Labor force by occupation |

|

| Unemployment |

|

| Average gross salary | Mex$12,887 / $732.31 monthly (2022) |

| Average net salary | Mex$11,434 / $649.49 monthly (2022) |

| Main industries | |

| External | |

| Exports | |

| Export goods | manufactured goods, electronics, vehicles and auto parts, oil and oil products, silver, plastics, fruits, vegetables, coffee, cotton |

| Main export partners |

|

| Imports | |

| Import goods | metalworking machines, steel mill products, agricultural machinery, electrical equipment, automobile parts for assembly and repair, aircraft, aircraft parts, plastics, natural gas and oil products |

| Main import partners |

|

| FDI stock |

|

| Current account | |

| Gross external debt | |

| Public finances | |

| Government debt | |

| Budget balance | −1.1% (of GDP) (2017 est.) |

| Revenues | 261.4 billion (2017 est.) |

| Expenses | 273.8 billion (2017 est.) |

| Economic aid | $189.4 million (2008) |

| Credit rating |

|

| Foreign reserves | |

| All values, unless otherwise stated, are in US dollars. | |

The economy of Mexico is a developing mixed-market economy. It is the 13th largest in the world in nominal GDP terms and by purchasing power parity as of 2024. Since the 1994 crisis, administrations have improved the country's macroeconomic fundamentals. Mexico was not significantly influenced by the 2002 South American crisis, and maintained positive, although low, rates of growth after a brief period of stagnation in 2001. However, Mexico was one of the Latin American nations most affected by the 2008 recession with its gross domestic product contracting by more than 6% in that year. Among OECD nations, Mexico has a fairly strong social security system; social expenditure stood at roughly 7.5% of GDP.

The Mexican economy has maintained high levels of macroeconomic stability, which has reduced inflation and interest rates to record lows. In spite of this, significant gaps persist between the urban and the rural population, the northern and southern states, and the rich and the poor. Some of the unresolved issues include the upgrade of infrastructure, the modernization of the tax system and labor laws, and the reduction of income inequality. Tax revenues, altogether 19.6 percent of GDP in 2013, were the lowest among the then 34 OECD countries. The main problems Mexico faces are poverty rates and regional inequalities remaining high. Productivity growth has been limited by the lack of formality, financial exclusion, and corruption. The medium term growth prospects were also affected by a lower proportion of women in the workforce, and investment has not been strong since 2015.

The economy contains rapidly developing modern industrial and service sectors, with increasing private ownership. Recent administrations have expanded competition in ports, railroads, telecommunications, electricity generation, natural gas distribution and airports, with the aim of upgrading infrastructure. As an export-oriented economy, more than 90% of Mexican trade is under free trade agreements (FTAs) with more than 40 countries, including the European Union, Japan, Israel, and much of Central and South America. The most influential FTA is the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA), which came into effect in 2020, and was signed in 2018 by the governments of the United States, Canada and Mexico. In 2006, trade with Mexico's two northern partners accounted for almost 90% of its exports and 55% of its imports. Recently, Congress approved important tax, pension, and judicial reforms. In 2023, Mexico had 13 companies in the Forbes Global 2000 list of the world's largest companies.

Mexico's labor force consisted of 52.8 million people as of 2015. The OECD and WTO both rank Mexican workers as the hardest-working in the world in terms of the number of hours worked yearly. Pay per hours worked remains low.

Mexico is a highly unequal country: 0.2% of the population owns 60% of the country's wealth, while 46.8 million people live in poverty (2024).

History

Main article: Economic history of Mexico

The Porfiriato brought unprecedented economic growth during the last quarter of the nineteenth century. This growth was accompanied by foreign investment and European immigration, the development of railroad networks and the exploitation of the country's natural resources. Annual economic growth between 1876 and 1910 averaged 3.3%. Large-scale ownership made considerable progress while foreign land companies accumulated millions of hectares. At the end of Porfirio Díaz's dictatorship, 97% of arable land belonged to 1% of the population and 95% of peasants were landless, becoming farmworkers in huge haciendas or forming an impoverished urban proletariat whose revolts were crushed one by one.

Political repression and fraud, as well as huge income inequalities exacerbated by the land distribution system based on latifundios, in which large haciendas were owned by a few but worked by millions of impoverished peasants living in precarious conditions, led to the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920), an armed conflict that drastically transformed Mexico's political, social, cultural, and economic structure during the twentieth century. The war itself left a harsh toll on the economy and population, which decreased over the 11-year period between 1910 and 1921. The reconstruction of the country was to take place in the following decades.

The period from 1940 to 1970 has been dubbed by economic historians as the Mexican Miracle, a period of economic growth that followed the end of the Mexican Revolution and the resumption of capital accumulation during peacetime. During this period, Mexico adopted an import substitution industrialization (ISI) model, which protected and promoted the development of national industries. Mexico experienced an economic boom through which industries rapidly expanded their production. Important changes in the economic structure included free land distribution to peasants under the concept of ejido, the nationalization of the oil and railroad companies, the introduction of social rights into the 1917 Constitution, the birth of large and influential labor unions, and the upgrading of infrastructure. While population doubled from 1940 to 1970, GDP increased sixfold during the same period.

Growth while under the ISI model had reached its peak in the late 1960s. During the 1970s, the presidential administrations of Luis Echeverría (1970–76) and José López Portillo (1976–82) tried to include social development in their policies, an effort that entailed increased public spending. With the discovery of vast oil fields during a period of oil price increases and low international interest rates, the government borrowed from international capital markets to invest in the state-owned oil company Pemex, which in turn seemed to provide a long-run income source to promote social welfare. This produced a remarkable growth in public expenditure, and president López Portillo announced that the time had come to "manage prosperity" as Mexico multiplied its oil production to become the world's fourth-largest exporter.

| Average annual GDP growth by period | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1900–1929 | 3.4% | |

| 1929–1945 | 4.2% | |

| 1945–1972 | 6.5% | |

| 1972–1981 | 5.5% | |

| 1981–1995 | 1.5% | |

| 1983 Debt Crisis | -4.2% | |

| 1995 Peso Crisis | -6.2% | |

| 1995–2000 | 5.1% | |

| 2001 US Recession | -0.2% | |

| 2009 Great Recession | -6.5% | |

| Sources: | ||

In the period of 1981–1982 the international panorama changed abruptly: oil prices plunged and interest rates rose. In 1982, López Portillo, just before ending his administration, suspended payments of foreign debt, devalued the peso and nationalized the banking system, along with many other industries that were severely affected by the crisis, among them the steel industry. While import substitution had contributed to Mexican industrialization, by the 1980s protracted protection of Mexican companies had led to an uncompetitive industrial sector with low productivity gains.

President Miguel de la Madrid (1982–88) was the first of a series of presidents that implemented neoliberal policies. After the crisis of 1982, lenders were unwilling to return to Mexico and, in order to keep the current account in balance, the government resorted to currency devaluations, which sparked unprecedented inflation, reaching an annual record of 139.7% in 1987.

One of the first steps toward trade liberalization was Mexico's signature of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1986 under President de la Madrid. During the administration of Carlos Salinas de Gortari (1988–94) many state-owned companies were privatized. The telephone company Telmex, a government monopoly, became a private monopoly, sold to Carlos Slim. Also not opened to private investors were the government oil company Pemex or the energy sector. Furthermore, the banking system that had been nationalized in the waning hours of the López Portillo administration in 1982 were privatized, but with the exclusion of foreign banks. Salinas pushed for Mexico's inclusion in the North American Free Trade Agreement, expanding it from a U.S.-Canada agreement. The expanded NAFTA was signed in 1992, after the signature of two additional supplements on environments and labor standards, it came into effect on January 1, 1994.

Salinas also introduced strict price controls and negotiated smaller minimum wage increments with the labor union movement under the aging Fidel Velázquez with the aim of curbing inflation. While his strategy was successful in reducing inflation, growth averaged only 2.8 percent a year. By fixing the exchange rate, the peso became rapidly overvalued while consumer spending increased, causing the current account deficit to reach 7% of GDP in 1994. The deficit was financed through tesobonos a type of public debt instrument that reassured payment in dollars.

The January 1994 Chiapas uprising, and the assassinations of the ruling party's presidential candidate in March 1994, Luis Donaldo Colosio and the Secretary-General of the party and brother of the Assistant-Attorney General José Francisco Ruiz Massieu in 1994, reduced investor confidence. Public debt holders rapidly sold their tesobonos, depleting the Central Bank's reserves, while portfolio investments, which had made up 90% of total investment flows, left the country as fast as they had come in.

This unsustainable situation eventually forced the entrant Zedillo administration to adopt a floating exchange rate. The peso sharply devalued and the country entered into an economic crisis in December 1994. The boom in exports, as well as an international rescue package crafted by U.S. president Bill Clinton (1993-2001), helped cushion the crisis. In less than 18 months, the economy was growing again, and annual rate growth averaged 5.1 percent between 1995 and 2000. More critical interpretations argue that the crisis and subsequent public bailout "preserved, renewed, and intensified the structurally unequal social relations of power and class characteristic of finance-led neoliberal capitalism" in forms institutionally specific to Mexican society, with GDP growth spurred by one-time privatizations. Per capita economic growth in the 2000s was low.

President Ernesto Zedillo (1994–2000), and President Vicente Fox (2000–06), of the National Action Party (Mexico), the first opposition party candidate to win a presidential election since the founding of the precursor of the Institutional Revolutionary Party in 1929, continued with trade liberalization. During Fox's administrations, several FTAs were signed with Latin American and European countries, Japan and Israel, and both strove to maintain macroeconomic stability. Thus, Mexico became one of the most open countries in the world to trade, and the economic base shifted accordingly. Total trade with the United States and Canada tripled, and total exports and imports almost quadrupled between 1991 and 2003. The nature of foreign investment also changed with a greater share of foreign-direct investment (FDI) over portfolio investment. The wealth of Mexico's leading billionaires stems from the privatizations of the 1990s, when the country sold off its state-owned companies at low prices: telecoms (Telmex) to Carlos Slim, trains (Ferromex) to German Larrea, and television (TV Azteca) to Ricardo Salinas.

Macroeconomic, financial and welfare indicators

Main indicators

| GDP per capita PPP | US $16,900 (2012–15) |

|---|---|

| GNI per capita PPP | US $16,500 (2012–15) |

| Inflation (CPI) | 3.7% (February 2021) |

| Gini index | 43.4 (World Bank 2016) |

| Unemployment | 4.5% (January 2021) |

| HDI | |

| Labor force | 78.4 million (2011) |

| Pop. in poverty | 13.8% |

Mexico's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in purchasing power parity (PPP) was estimated at US$2,143.499 billion in 2014, and $1,261.642 billion in nominal exchange rates. It is the leader of the MINT group. Its standard of living, as measured in GDP in PPP per capita, was US$16,900. The World Bank reported in 2009 that Mexico's Gross National Income in market exchange rates was the second highest in Latin America, after Brazil at US$1,830.392 billion, which lead to the highest income per capita in the region at $14,400. As such, Mexico established itself as an upper middle-income country. After the slowdown of 2001 the country has recovered and has grown 4.2, 3.0 and 4.8 percent in 2004, 2005 and 2006, even though it is considered to be well below Mexico's potential growth.

The Mexican peso is the currency (ISO 4217: MXN; symbol: $). One peso is divided into 100 centavos (cents). MXN replaced MXP in 1993 at a rate of 1000 MXP per 1 MXN. The exchanged rate remained stable between 1998 and 2006, oscillating between 10.20 and 11=3.50 MXN per US$. The Mexican peso parity decreased under president Enrique Peña Nieto, lost in a single year 19.87% of its value Archived March 29, 2017, at the Wayback Machine reaching an exchange rate of $20.37 per dollar in 2017. Interest rates in 2007 were situated at around 7 percent, having reached a historic low in 2002 below 5 percent. Inflation rates are also at historic lows; the inflation rate in Mexico in 2006 was 4.1 percent, and 3 percent by the end of 2007. Compared against the US Dollar, Mexican Peso has devalued over %7,500 since 1910.

Unemployment rates are the lowest of all OECD member countries at 3.2 percent. However, underemployment is estimated at 25 percent. Mexico's Human Development Index was reported at 0.829 in 2008, (comprising a life expectancy index of 0.84, an education index of 0.86 and a GDP index of 0.77), ranking 52 in the world within the group of high-development.

Development

The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1980–2023 (with IMF staff estimates in 2024–2028). Inflation below 5% is in green.

| Year | GDP

(in billion US$PPP) |

GDP per capita

(in US$ PPP) |

GDP

(in billion US$nominal) |

GDP per capita

(in US$ nominal) |

GDP growth

(real) |

Inflation rate

(in Percent) |

Unemployment

(in Percent) |

Government debt

(in % of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 404.3 | 5,984.8 | 228.6 | 3,383.7 | 1.2% | n/a | ||

| 1981 | n/a | |||||||

| 1982 | n/a | |||||||

| 1983 | n/a | |||||||

| 1984 | n/a | |||||||

| 1985 | n/a | |||||||

| 1986 | n/a | |||||||

| 1987 | n/a | |||||||

| 1988 | n/a | |||||||

| 1989 | n/a | |||||||

| 1990 | n/a | |||||||

| 1991 | n/a | |||||||

| 1992 | n/a | |||||||

| 1993 | n/a | |||||||

| 1994 | n/a | |||||||

| 1995 | n/a | |||||||

| 1996 | 44.7% | |||||||

| 1997 | ||||||||

| 1998 | ||||||||

| 1999 | ||||||||

| 2000 | ||||||||

| 2001 | ||||||||

| 2002 | ||||||||

| 2003 | ||||||||

| 2004 | ||||||||

| 2005 | ||||||||

| 2006 | ||||||||

| 2007 | ||||||||

| 2008 | ||||||||

| 2009 | ||||||||

| 2010 | ||||||||

| 2011 | ||||||||

| 2012 | ||||||||

| 2013 | ||||||||

| 2014 | ||||||||

| 2015 | ||||||||

| 2016 | ||||||||

| 2017 | ||||||||

| 2018 | ||||||||

| 2019 | ||||||||

| 2020 | ||||||||

| 2021 | ||||||||

| 2022 | ||||||||

| 2023 | ||||||||

| 2024 | ||||||||

| 2025 | ||||||||

| 2026 | ||||||||

| 2027 | ||||||||

| 2028 |

Poverty

Main article: Poverty in Mexico

Poverty in Mexico is measured under parameters such as nutrition, clean water, shelter, education, health care, social security, quality and basic services in the household, income and social cohesion as defined by social development laws in the country. It is divided in two categories: Moderate poverty and Extreme poverty.

While less than 2% of Mexico's population lives below the international poverty line set by the World Bank, as of 2013, Mexico's government estimates that 33% of Mexico's population lives in moderate poverty and 9% lives in extreme poverty, which leads to 42% of Mexico's total population living below the national poverty line. The gap might be explained by the government's adopting the multidimensional poverty method as a way to measure poverty, so a person who has an income higher than the "international poverty line" or "well being income line" set by the Mexican government might fall in the "moderate poverty" category if he or she has one or more deficiencies related to social rights such as education (did not complete studies), nutrition (malnutrition or obesity), or living standards (including elemental, such as water or electricity, and secondary domestic assets, such as refrigerators). Extreme poverty is defined by the Mexican government as persons who have deficiencies in both social rights and an income lower than the "well being income line". Additional figures from SEDESOL (Mexico's social development agency) estimates that 6% (7.4 million people) live in extreme poverty and suffer from food insecurity.

Recently, extensive changes in government economic policy and attempts at reducing government interference through privatization of several sectors, for better or worse, allowed Mexico to remain the biggest economy in Latin America, until 2005 when it became the second-largest; and a so-called "trillion dollar club" member. Despite these changes, Mexico continues to suffer great social inequality and lack of opportunities. The Peña Nieto's administration made an attempt at reducing poverty in the country, to provide more opportunities to its citizens such as jobs, education, and the installation of universal healthcare.

Income inequality

A single person in Mexico, Carlos Slim, has a net worth equal to six percent of GDP. Additionally, only ten percent of Mexicans represent 25% of Mexican GDP. A smaller group, 3.5%, represent 12.5% of Mexican GDP.

According to the OECD, Mexico is the country with the second highest degree of economic disparity between the extremely poor and extremely rich, after Chile – although this gap has been diminishing over the last decade. The bottom ten percent on the income rung disposes of 1.36% of the country's resources, whereas the upper 10% dispose of almost 36%. OECD also notes that Mexico's budgeted expenses for poverty alleviation and social development is only about a third of the OECD average – both in absolute and relative numbers. According to the World Bank, in 2004, 17.6% of Mexico's population lived in extreme poverty, while 21% lived in moderated poverty.

Remittances

Mexico was the fourth largest receiver of remittances in the world in 2017. Remittances, or contributions sent by Mexicans living abroad, mostly in the United States, to their families at home in Mexico comprised $28.5 billion in 2017. In 2015, remittances overtook oil to become the single largest foreign source of income for Mexico, larger than any other sector.

The growth of remittances have more than doubled since 1997. Recorded remittance transactions exceeded 41 million in 2003, of which 86 percent were made by electronic transfer.

The Mexican government, cognizant of the needs of migrant workers, began issuing an upgraded version of the Matrícula Consular de Alta Seguridad (MACS, High Security Consular Identification), an identity document issued at Mexican consulates abroad. This document is now accepted as a valid identity card in 32 US states, as well as thousands of police agencies, hundreds of cities and counties, as well as banking institutions.

The main states receiving remittances in 2014 were Michoacán, Guanajuato, Jalisco, the State of Mexico and Puebla, which jointly captured 45% of total remittances in that year. Several state governments, with the support of the federal government, have implemented programs to use part of the remittances to finance public works. This program, called Dos por Uno (Two for every one) is designed in a way that for each peso contributed by migrants from their remittances, the state and the federal governments will invest two pesos in building infrastructure at their home communities.

Regional economies

Further information: List of Mexican states by GDP and List of Mexican states by GDP per capita

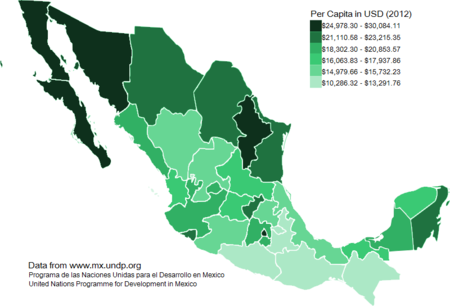

Regional disparities and income inequality are a feature of the Mexican economy. While all constituent states of the federation have a Human Development Index (HDI) higher than 0.70 (medium to high development), the northern and central states have higher levels of HDI than the southern states. Nuevo León, Jalisco and the Federal District have HDI levels similar to European countries, whereas that of Oaxaca and Chiapas is similar to that of China or Vietnam.

At the municipal level, economic disparities are even greater: Benito Juárez borough in Mexico City has an HDI similar to that of Germany or New Zealand, whereas, Metlatónoc in Guerrero, would have an HDI similar to that of Malawi. The majority of the federal entities in the north have a high development (higher than 0.80), as well as the entities Colima, Jalisco, Aguascalientes, the Federal District, Querétaro and the southeastern states of Quintana Roo and Campeche). The less developed states (with medium development in terms of HDI, higher than 0.70) are located along the southern Pacific coast.

In terms of share of the GDP by economic sector (in 2004), the largest contributors in agriculture are Jalisco (9.7%), Sinaloa (7.7%) and Veracruz (7.6%); the greatest contributors in industrial production are the Federal District (15.8%), State of México (11.8%) and Nuevo León (7.9%); the greatest contributors in the service sector are also the Federal District (25.3%), State of México (8.9%) and Nuevo León (7.5%).

Since the 1980s, the economy has slowly become less centralized; the annual rate of GDP growth of the Federal District from 2003 to 2004 was the smallest of all federal entities at 0.2%, with drastic drops in the agriculture and industrial sectors. Nonetheless, it still accounts for 21.8% of the nation's GDP. The states with the highest GDP growth rates are Quintana Roo (9.0%), Baja California (8.9%), and San Luis Potosí (8.2%). In 2000, the federal entities with the highest GDP per capita in Mexico were the Federal District (US$26,320), Campeche (US$18,900) and Nuevo León (US$30,250); the states with the lowest GDP per capita were Chiapas (US$3,302), Oaxaca (US$4,100) and Guerrero (US$6,800).

Companies

See also: List of companies of Mexico and List of largest Mexican companiesOf the world's 2000 largest companies, ranked in the Forbes Global 2000, 13 are headquartered in Mexico. 3 are also included among the 500 largest, measured by the Fortune Global 500.

The list includes the largest Mexican companies in 2023:

| Rank | Forbes 2000 rank |

Name | Headquarters | Revenue (billions US$) |

Industry |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 177 | América Móvil | Mexico City | 43.57 | Telecommunications |

| 2 | 312 | Fomento Económico Mexicano | Monterrey | 35.86 | Beverages |

| 3 | 375 | Banorte | Monterrey | 16.82 | Finance |

| 4 | 496 | Grupo México | Mexico City | 13.93 | Mining |

| 5 | 610 | Grupo Bimbo | Mexico City | 20.74 | Food processing |

| 6 | 1048 | Inbursa | Mexico City | 4 | Financial services |

| 7 | 1071 | Cemex | Monterrey | 15.93 | Building material |

| 8 | 1130 | Arca Continental | Monterrey | 10..8 | Beverages |

| 9 | 1188 | Grupo Carso | Mexico City | 10.18 | Conglomerate |

| 10 | 1384 | ALFA | Monterrey | 18.27 | Conglomerate |

| 11 | 1558 | El Puerto de Liverpool | Mexico City | 8.75 | Retail |

| 12 | 1606 | Grupo Elektra | Mexico City | 8.19 | Finance |

| 13 | 1743 | Fibra Uno | Mexico City | 1.17 | Real Estate |

Economic sectors

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in purchasing power parity (PPP) in 2024 was estimated at US$3,43 trillion, and GDP per capita in PPP at US$25,963. The service sector is the largest component of GDP at 70.5%, followed by the industrial sector at 25.7% (2006 est.). Agriculture represents only 3.9% of GDP (2006 est.). Mexican labor force is estimated at 38 million of which 18% is occupied in agriculture, 24% in the industry sector and 58% in the service sector (2003 est.). Mexico's largest source of foreign income is remittances.

Agriculture

Further information: Agriculture in MexicoAgriculture as a percentage of total GDP has been steadily declining, and now resembles that of developed nations in that it plays a smaller role in the economy. In 2006, agriculture accounted for 3.9% of GDP, down from 7% in 1990, and 25% in 1970. Given the historic structure of ejidos, it employs a considerably high percentage of the work force: 18% in 2003, mostly of which grows basic crops for subsistence, compared to 2–5% in developed nations in which production is highly mechanized.

History

| Food and agriculture | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Farmers in Puebla | ||

| Product | Quantity (Tm) | World Rank |

| Avocados | 1,040,390 | 1 |

| Onions and chayote | 1,130,660 | 1 |

| Limes and lemons | 1,824,890 | 1 |

| Sunflower seed | 212,765 | 1 |

| Dry fruits | 95,150 | 2 |

| Papaya | 955,694 | 2 |

| Chillies and peppers | 1,853,610 | 2 |

| Whole beans | 93 000 | 3 |

| Oranges | 3,969,810 | 3 |

| Anise, badian, fennel | 32 500 | 3 |

| Chicken meat | 2,245,000 | 3 |

| Asparagus | 67,247 | 4 |

| Mangoes | 1.503.010 | 4 |

| Corn | 20,000,000 | 4 |

| Source:FAO | ||

After the Mexican Revolution, Mexico began an agrarian reform, based on the 27th article of the Mexican Constitution than included transfer of land and/or free land distribution to peasants and small farmers under the concept of the ejido. This program was further extended during President Cárdenas' administration during the 1930s and continued into the 1960s at varying rates. The cooperative agrarian reform, which guaranteed small farmers a means of subsistence livelihood, also caused land fragmentation and lack of capital investment, since commonly held land could not be used as collateral. In an effort to raise rural productivity and living standards, this constitutional article was amended in 1992 to allow for the transfer of property rights of the communal lands to farmers cultivating it. With the ability to rent or sell it, a way was open for the creation of larger farms and the advantages of economies of scale. Large mechanized farms are now operating in some northwestern states (mainly in Sinaloa). However, privatization of ejidos continues to be very slow in the central and southern states where the great majority of peasants produce only for subsistence.

Until the 1980s, the government encouraged the production of basic crops (mainly corn and beans) by maintaining support prices and controlling imports through the National Company for Popular Subsistence (CONASUPO). With trade liberalization, however, CONASUPO was gradually dismantled and two new mechanisms were implemented: Alianza and Procampo. Alianza provides income payments and incentives for mechanization and advanced irrigation systems. Procampo is an income transfer subsidy to farmers. This support program provides 3.5 million farmers who produce basic commodities (mostly corn), and which represent 64% of all farmers, with a fixed income transfer payment per unit of area of cropland. This subsidy increased substantially during president Fox's administration, mainly to white corn producers in order to reduce imports from the United States. This program has been successful, and in 2004, roughly only 15% of corn imports are white corn –the one used for human consumption and the type that is mostly grown in Mexico– as opposed to 85% of yellow and crashed corn –the one use for feeding livestock, and which is barely produced in Mexico.

Crops

In spite of corn as being a staple in the Mexican diet, Mexico's comparative advantage in agriculture is not in corn, but in horticulture, tropical fruits, and vegetables. Negotiators of NAFTA expected that through liberalization and mechanization of agriculture two-thirds of Mexican corn producers would naturally shift from corn production to horticultural and other labor-intensive crops such as fruits, nuts, vegetables, coffee and sugar cane. While horticultural trade has drastically increased due to NAFTA, it has not absorbed displaced workers from corn production (estimated at 600,000). Corn production has remained stable (at 20 million metric tons), arguably, as a result of income support to farmers, or a reluctance to abandon a millenarian tradition in Mexico: not only have peasants grown corn for millennia, corn originated in Mexico. Mexico is the seventh largest corn producer in the world.

Potatoes

The area dedicated to potatoes has changed little since 1980 and average yields have almost tripled since 1961. Production reached a record 1.7 million tonnes in 2003. Per capita consumption of potato in Mexico stands at 17 kg a year, very low compared to its maize intake of 400 kg. On average, potato farms in Mexico are larger than those devoted to more basic food crops. Potato production in Mexico is mostly for commercial purposes; the production for household consumption is very small.

Avocado

Mexico is by far the world's largest avocado growing country, producing several times more than the second largest producer. In 2013, the total area dedicated to avocado production was 188,723 hectares (466,340 acres), and the harvest was 2.03 million tonnes in 2017. The state that produces the most is Michoacán, which produces nearly 75% of all Mexican avocados.

Sugar cane

Approximately 160,000 medium-sized farmers grow sugar cane in 15 Mexican states; currently there are 54 sugar mills around the country that produced 4.96 million tons of sugar in the 2010 crop, compared to 5.8 million tons in 2001. Mexico's sugar industry is characterized by high production costs and lack of investment. Mexico produces more sugar than it consumes. Sugar cane is grown on 700,000 farms in Mexico with a yield of 72 metric tons per farm.

Mining

In 2019, the country was the world's largest producer of silver 9th largest producer of gold, the 8th largest producer of copper, the world's 5th largest producer of lead, the world's 6th largest producer of zinc, the world's 5th largest producer of molybdenum, the world's 3rd largest producer of mercury, the world's 5th largest producer of bismuth, the world's 13th largest producer of manganese and the 23rd largest world producer of phosphate. It is also the 8th largest world producer of salt.

In April 2022, the Senate passed a law that nationalizes the lithium mining industry in the country. The federal government will have a monopoly on all new lithium mines in the country, but existing operations will be allowed to continue in private hands. Critics of the move argue that the constitution already does this and that the government lacks the technical capacity to mine the major reserves, which are mostly in clay deposits that are difficult to mine. The government made a similar failed attempt to nationalize uranium mining in the 1980s.

Industry

| Industrial production | ||

|---|---|---|

| Main industries | Aircraft, automobile industry, petrochemicals, cement and construction, textiles, food and beverages, mining, consumer durables, tourism | |

| Industrial growth rate | 3.6% (2006) | |

| Labor force | 29% of total labor force | |

| GDP of sector | 25.7% of total GDP | |

The industrial sector as a whole has benefited from trade liberalization; in 2000 it accounted for almost 50% of all export earnings.

Among the most important industrial manufacturers in Mexico is the automotive industry, whose standards of quality are internationally recognized. The automobile sector in Mexico differs from that in other Latin American countries and developing nations in that it does not function as a mere assembly manufacturer. The industry produces technologically complex components and engages in some research and development activities, an example of that is the new Volkswagen Jetta model with up to 70% of parts designed in Mexico.

The "Big Three" (General Motors, Ford and Chrysler) have been operating in Mexico since the 1930s, while Volkswagen and Nissan built their plants in the 1960s. Later, Toyota, Honda, BMW, and Mercedes-Benz have also participated. Given the high requirements of North American components in the industry, many European and Asian parts suppliers have also moved to Mexico: in Puebla alone, 70 industrial part-makers cluster around Volkswagen.

The relatively small domestic car industry is represented by DINA Camiones, a manufacturer of trucks, busses and military vehicles, which through domestic production and purchases of foreign bus manufacturers has become the largest bus manufacturer in the world; Vehizero that builds hybrid trucks and the new car companies Mastretta design that builds the Mastretta MXT sports car and Autobuses King that plans to build 10000 microbuses by 2015, nevertheless new car companies are emerging among them CIMEX that has developed a sport utility truck, the Conin, and it is to be released in September 2010 in Mexico's national auto show, And the new electric car maker Grupo Electrico Motorizado. Some large industries of Mexico include Cemex, the world's largest construction company and the third largest cement producer the alcohol beverage industries, including world-renowned players like Grupo Modelo; conglomerates like FEMSA, which apart from being the largest single producer of alcoholic beverages and owning multiple commercial interests such OXXO convenience store chain, is also the second-largest Coca-Cola bottler in the world; Gruma, the largest producer of corn flour and tortillas in the world; and Grupo Bimbo, Telmex, Televisa, among many others. In 2005, according to the World Bank, high-tech industrial production represented 19.6% of total exports.

Maquiladoras (manufacturing plants that take in imported raw materials and produce goods for domestic consumption and export on behalf of foreign companies) have become the landmark of trade in Mexico. This sector has benefited from NAFTA, in that real income in the maquiladora sector has increased 15.5% since 1994, though from the non-maquiladora sector has grown much faster. Contrary to popular belief, this should be no surprise since maquiladora's products could enter the US duty-free since a 1960s industry agreement. Other sectors now benefit from the free trade agreement, and the share of exports from non-border states has increased in the last 5 years while the share of exports from maquiladora-border states has decreased.

Currently Mexico is focusing in developing an aerospace industry and the assembly of helicopter and regional jet aircraft fuselages is taking place. Foreign firms such as MD Helicopters, Bell, Cessna and Bombardier build helicopter, aircraft and regional jets fuselages in Mexico. Although the Mexican aircraft industry is mostly foreign, as is its car industry, Mexican firms have been founded such as Aeromarmi, which builds light propeller airplanes, and Hydra Technologies, which builds Unmanned Aerial Vehicles such as the S4 Ehécatl, other important companies are Frisa Aerospace that manufactures jet engine parts for the new Mitsubishi Regional jet and supplies Prat&whittney and Rolls-Royce jet engine manufacturers of casings for jet engines and Kuo Aerospace that builds parts for aircraft landing gear and Supplies bombardier plant in Querétaro.

As compared with the United States or countries in Western Europe, a larger sector of Mexico's industrial economy is food manufacturing, which includes several world class companies but the regional industry is undeveloped. There are national brands that have become international and local Mom and Pop producers but little manufacturing in between.

Electronics

The electronics industry of Mexico has grown enormously within the last decade. Mexico has the sixth largest electronics industry in the world after China, United States, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Mexico is the second largest exporter of electronics to the United States where it exported $71.4 billion worth of electronics in 2011. The Mexican electronics industry is dominated by the manufacture and OEM design of televisions, displays, computers, mobile phones, circuit boards, semiconductors, electronic appliances, communications equipment and LCD modules. The Mexican electronics industry grew 20% between 2010 and 2011, up from its constant growth rate of 17% between 2003 and 2009. Currently electronics represent 30% of Mexico's exports.

Televisions

The design and manufacture of flat panel plasma, LCD and LED televisions is the single largest sector of the Mexican electronics industry, representing 25% of Mexico's electronics export revenue. In 2009 Mexico surpassed South Korea and China as the largest manufacturer of televisions, with Sony, Toshiba, Samsung, Sharp (through Semex), Zenith LG, Lanix, TCL, RCA, Phillips, Elcoteq, Tatung, Panasonic, and Vizio manufacturing CRT, LCD, LED and Plasma televisions in Mexico. Due to Mexico's position as the largest manufacturer of televisions it is known as the television capital of the world in the electronics industry.

Computers

Mexico is the third largest manufacturers of computers in the world with both domestic companies such as Lanix, Texa, Meebox, Spaceit, Kyoto and foreign companies such as Dell, Sony, HP, Acer Compaq, Samsung and Lenovo manufacturing various types of computers across the country. Most of the computers manufactured in Mexico are from foreign companies. Mexico is Latin America's largest producer of electronics and appliances made by domestic companies.

OEM and ODM manufacturing

Mexico is also home to a large number of OEM and ODM manufactures both foreign and domestic. Among them include Foxconn, Celestica, Sanmina-SCI, Jabil, Elcoteq, Falco, Kimball International, Compal, Benchmark Electronics, Plexus, Lanix and Flextronics. These companies assemble finished electronics or design and manufacture electronic components on behalf of larger companies such as Sony or Microsoft using locally sourced components, for example the ODM, Flextronics manufactures Xbox video games systems in Guadalajara, Mexico for Microsoft using components such as power systems and printed circuit boards from a local company, Falco Electronics which acts as the OEM.

Engineering and design

The success and rapid growth of the Mexican electronics sector is driven primarily by the relatively low cost of manufacturing and design in Mexico; its strategic position as a major consumer electronics market coupled with its proximity to both the large North American and South American markets whom Mexico shares free trade agreements with; government support in the form of low business taxes, simplified access to loans and capital for both foreign multinational and domestic startup tech-based firms; and a very large pool of highly skilled, educated labor across all sectors of the tech industry. For example, German multinational engineering and electronics conglomerate Siemens has a significant Mexican base, which also serves as its business and strategy hub for Central American countries and the Caribbean region.

There are almost half a million (451,000) students enrolled in electronics engineering programs with an additional 114,000 electronics engineers entering the Mexican workforce each year and Mexico had over half a million (580,000) certified electronic engineering professionals employed in 2007. From the late 1990s, the Mexican electronics industry began to shift away from simple line assembly to more advanced work such as research, design, and the manufacture of advanced electronics systems such as LCD panels, semiconductors, printed circuit boards, microelectronics, microprocessors, chipsets and heavy electronic industrial equipment and in 2006 the number of certified engineers being graduated annually in Mexico surpassed that of the United States. Many Korean, Japanese and American appliances sold in the US are actually of Mexican design and origin but sold under the OEM's client names. In 2008 one out of every four consumer appliances sold in the United States was of Mexican design.

Joint production

While many foreign companies like Phillips, Vizio and LG simply install wholly owned factories in Mexico; a number of foreign companies have set up semi-independent joint venture companies with Mexican businesses to manufacture and design components in Mexico. These companies are independently operated from their foreign parent companies and are registered in Mexico. These local companies function under Mexican law and retain a sizable portion of the revenue. These companies typically function dually as in-company OEM development and design facilities and manufacturing centers and usually produce most components needed to manufacture the finished products. An example would by Sharp which has formed Semex.

Semex was founded as a joint venture between Sharp and Mexican investors which acts as an autonomous independent company which Sharp only maintains partial control over. The company manufactures whole products such televisions and designs individual components on behalf of Sharp such as LCD modules and in return Semex is granted access to Sharp capital, technology, research capacity and branding. Notable foreign companies which have set up joint venture entities in Mexico include Samsung which formed Semex, a local designer and manufacturer of finished televisions, white goods and individual electronic components like printed circuit boards, LCD panels and semiconductors, Toshiba, who formed Toshiba de México, S.A. de C.V., an administratively autonomous subsidiary which produces electronics parts, televisions and heavy industrial equipment.

Some of these subsidiaries have grown to expand into multiple branches effectively becoming autonomous conglomerates within their own parent companies. Sony for example started operations in Mexico in 1976 with a group of Mexican investors, and founded the joint venture, Sony de Mexico which produces LED panels, LCD modules, automotive electronics, appliances and printed circuit boards amongst other products for its Japanese parent company, Sony KG. Sony de Mexico has research facilities in Monterrey and Mexico City, designs many of the Sony products manufactured in Mexico and has now expanded to create its own finance, music and entertainment subsidiaries which are Mexican registered and independent of their Japanese parent corporation.

Domestic industry

Although much of Mexico's electronics industry is driven by foreign companies, Mexico also has a sizeable domestic electronics industry and a number of electronics companies including Mabe, a major appliance manufacturer and OEM which has been functioning since the nineteen fifties and has expanded into the global market, Meebox, a designer and manufacturer desktop and tablet computers, solar power panels and electronics components, Texa, which manufactures computers laptops and servers, Falco, a major international manufacturer of electronic components such as printed circuitboards, power systems, semiconductors, gate drives and which has production facilities in Mexico, India and China, and Lanix, Mexico's largest electronics company which manufactures products such as computers, laptops, smartphones, LED and LCDs, flash memory, tablets, servers, hard drives, RAM, optical disk drives, and printed circuitboards and employs over 11,000 people in Mexico and Chile and distributes its products throughout Latin America. Another area being currently developed in Mexico is Robotics, Mexico's new Mexone robot has been designed with the idea that in future years develop a commercial application for such advanced robots

Oil

Further information: Petroleum industry in Mexico

Mineral resources are public property by constitution. As such, the energy sector is administered by the government with varying degrees of private investment. Mexico is the fourteenth-largest oil producer in the world, with 1,710,303 barrels per day (271,916.4 m/d). Pemex, the state-owned company in charge of administering research, exploration and sales of oil, is the largest company in Mexico, and the second largest in Latin America after Brazil's Petrobras. Pemex is heavily taxed of almost 62 per cent of the company's sales, a significant source of revenue for the government.

Without enough money to continue investing in finding new sources or upgrading infrastructure, and being protected constitutionally from private and foreign investment, some have predicted the company may face institutional collapse. While the oil industry is still relevant for the government's budget, its importance in GDP and exports has steadily fallen since the 1980s. In 1980 oil exports accounted for 61.6% of total exports; by 2000 it was only 7.3%.

Energy

Further information: Electricity sector in MexicoMexico's installed electricity capacity in 2008 was 58 GW. Of the installed capacity, 75% is thermal, 19% hydro, 2% nuclear and 3% renewable other than hydro. The general trend in thermal generation is a decline in petroleum-based fuels and a growth in natural gas and coal. Since Mexico is a net importer of natural gas, higher levels of natural gas consumption (i.e. for power generation) will likely depend upon higher imports from either the United States or via liquefied natural gas (LNG).

Manufacturing

Further information: Manufacturing in Mexico

Manufacturing in Mexico grew rapidly in the late 1960s with the end of the US farm labor agreement known as the bracero program. This sent many farm laborers back into the Northern border region with no source of income. As a result, the US and Mexican governments agreed to The Border Industrialization Program, which permitted US companies to assemble products in Mexico using raw materials and components from the US with reduced duties. The Border Industrialization Program became known popularly as The Maquiladora Program or shortened to The Maquila Program.

Over the years, simple assembly operations in Mexico have evolved into complex manufacturing operations including televisions, automobiles, industrial and personal products. While inexpensive commodity manufacturing has flown to China, Mexico attracts U.S. manufacturers that need low-cost solutions near-by for higher value end products and just-in-time components.

Automobiles

Further information: Automotive industry in Mexico

The automotive sector accounts for 17.6% of Mexico's manufacturing sector. General Motors, Chrysler, Ford Motor Company, Nissan, Fiat, Renault, Honda, Toyota, and Volkswagen produce 2.8 million vehicles annually at 20 plants across the country, mostly in Puebla. Mexico manufactures more automobiles of any North American nation. The industry produces technologically complex components and engages in research and development.

The "Big Three" (General Motors, Ford and Chrysler) have been operating in Mexico since the 1930s, while Volkswagen and Nissan built their plants in the 1960s. In Puebla 70 industrial part-makers cluster around Volkswagen. In the 2010s expansion of the sector was surging. In 2014 more than $10 billion in investment was committed in the first few months of the year. Kia Motors in August 2014 announced plans for a $1 billion factory in Nuevo León. At the time Mercedes-Benz and Nissan were already building a $1.4 billion plant near Aguascalientes, while BMW was planning a $1-billion assembly plant in San Luis Potosí. Additionally, Audi began building a $1.3 billion factory at San José Chiapa near Puebla in 2013.

Retailing

Mexico has a MXN 4.027 trillion retail sector (2013, about US$300 billion at the 2013 exchange rate) including an estimated US$12 billion (2015) in e-commerce. The largest retailer is Walmart, while the largest Mexico-based retailers are Soriana super/hypermarkets, FEMSA incl. its OXXO convenience stores, Coppel (department store), Liverpool department stores, Chedraui super/hypermarkets, and Comercial Mexicana super/hypermarkets. While urban areas like Mexico City, Monterrey, and Guadalajara dominate in terms of retail infrastructure and consumer spending power, rural areas and smaller towns still present opportunities for retailers, especially those catering to local needs and preferences. Seasonal shopping patterns in Mexico can significantly impact retail sales. For instance, major holidays like Christmas, Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead), and Easter prompt increased spending on gifts, food, and decorations. International luxury brands have expanded their presence in Mexico, opening flagship stores in prestigious shopping districts such as Polanco in Mexico City, Santa Fe, and upscale malls like Antara Polanco and Centro Santa Fe.

Services

In 2013 the tertiary sector was estimated to account for 59.8% of Mexico's GDP. In 2011 services employed 61.9% of the working population. This section includes transportation, commerce, warehousing, restaurant and hotels, arts and entertainment, health, education, financial and banking services, telecommunications as well as public administration and defense. Mexico's service sector is strong, and in 2001 replaced Brazil's as the largest service sector in Latin America in dollar terms.

Tourism

Further information: Tourism in Mexico

Tourism is one of the most important industries in Mexico. It is the fourth largest source of foreign exchange for the country. Mexico is the eighth most visited country in the world (with over 20 million tourists a year).

Finance

Banking system

According to the IMF the Mexican banking system is strong, in which private banks are profitable and well-capitalized. The financial and banking sector is increasingly dominated by foreign companies or mergers of foreign and Mexican companies with the notable exception of Banorte. The acquisition of Banamex, one of the oldest surviving financial institutions in Mexico, by Citigroup was the largest US-Mexico corporate merger, at US$12.5 billion. The largest financial institution in Mexico is Bancomer associated to the Spanish BBVA.

The process of institution building in the financial sector in Mexico has evolved hand in hand with the efforts of financial liberalization and of inserting the economy more fully into world markets. Over the recent years, there has been a wave of acquisitions by foreign institutions such as US-based Citigroup, Spain's BBVA and the UK's HSBC. Their presence, along with a better regulatory framework, has allowed Mexico's banking system to recover from the 1994–95 peso crisis. Lending to the public and private sector is increasing and so is activity in the areas of insurance, leasing and mortgages. However, bank credit accounts for only 22% of GDP, which is significantly low compared to 70% in Chile. Credit to the Agricultural sector has fallen 45.5% in six years (2001 to 2007), and now represents about 1% of total bank loans. Other important institutions include savings and loans, credit unions (known as "cajas populares"), government development banks, “non-bank banks”, bonded warehouses, bonding companies and foreign-exchange firms.

A wave of acquisitions has left Mexico's financial sector in foreign hands. Their foreign-run affiliates compete with independent financial firms operating as commercial banks, brokerage and securities houses, insurance companies, retirement-fund administrators, mutual funds, and leasing companies.

Securities market

Mexico has a single securities market, the Mexican Stock Exchange (Bolsa Mexicana de Valores, known as the Bolsa). The market has grown steadily, with its main indices increasing by more than 600% in the last decade. It is Latin America's second largest exchange, after Brazil's. The total value of the domestic market capitalization of the BMV was calculated at US$409 billion at the end of 2011, and raised to US$451 billion by the end of February this year.

The Indice de Precios y Cotizaciones (IPC, the general equities index) is the benchmark stock index on the Bolsa. In 2005 the IPC surged 37.8%, to 17,802.71 from 12,917.88, backed by a stronger Mexican economy and lower interest rates. It continued its steep rise through the beginning of 2006, reaching 19,272.63 points at end-March 2006. The stockmarket also posted a record low vacancy rate, according to the central bank. Local stockmarket capitalisation totalled US$236bn at end-2005, up from US$170 bn at end-2004. As of March 2006 there were 135 listed companies, down from 153 a year earlier. Only a handful of the listed companies are foreign. Most are from Mexico City or Monterrey; companies from these two cities compose 67% of the total listed companies.

The IPC consists of a sample of 35 shares weighted according to their market capitalisation. The largest companies include America Telecom, the holding company that manages Latin America's largest mobile company, América Móvil; Telmex, Mexico's largest telephone company; Grupo Bimbo, world's biggest baker; and Wal-Mart de México, a subsidiary of the US retail company. The makeup of the IPC is adjusted every six months, with selection aimed at including the most liquid shares in terms of value, volume and number of trades.

Mexico's stock market is closely linked to developments in the US. Thus, volatility in the New York and Nasdaq stock exchanges, as well as interest-rate changes and economic expectations in the US, can steer the performance of Mexican equities. This is both because of Mexico's economic dependence on the US and the high volume of trading in Mexican equities through American Depositary Receipts (ADRs). Currently, the decline in the value of the dollar is making non-US markets, including Mexico's, more attractive.

Despite the recent gains, investors remain wary of making placements in second-tier initial public offerings (IPOs). Purchasers of new issues were disappointed after prices fell in numerous medium-sized companies that made offerings in 1996 and 1997. IPO activity in Mexico remains tepid and the market for second-tier IPOs is barely visible. There were three IPOs in 2005.

Government

Monetary and financial system and regulation

Banco de México

Banco de México is Mexico's central bank, an internally autonomous public institution whose governor is appointed by the president and approved by the legislature to which it is fully responsible. Banco de México's functions are outlined in the 28th article of the constitution and further expanded in the Monetary Law of the United Mexican States. Banco de México's main objective is to achieve stability in the purchasing power of the national currency. It is also the lender of last resort.

Currency policy

Mexico has a floating exchange rate regime.

The floating exchange originated with reforms initiated after the December 1994 peso crash which had followed an unsustainable adherence to a short band. Under the new system, Banco de México now makes no commitment to the level of the peso exchange rate, although it does employ an automatic mechanism to accumulate foreign reserves. It also possesses tools aimed at smoothing out volatility. The Exchange Rate Commission sets policy; it is made up of six members—three each from the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit (Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Publico—SHCP) and the central bank, with the SHCP holding the deciding vote.

In August 1996, Banco de México initiated a mechanism to acquire foreign reserves when the peso is strong, without giving the market signals about a target range for the exchange rate. The resulting high levels of reserves, mostly from petroleum revenues, have helped to improve the terms and conditions on debt Mexico places on foreign markets. However, there is concern that the government relies too heavily on oil income in order to build a healthy base of reserves. According to the central bank, international reserves stood at US$75.8 billion in 2007. In May 2003, Banco de México launched a program that sells U.S. dollars via a monthly auction, with the goal of maintaining a stable, but moderate, level of reserves.

From April 1, 1998, through April 1, 2008, the Peso traded around a range varying from $8.46 MXN per US$1.00 on April 21, 1998, to $11.69 MXN per US$1.00 on May 11, 2004, a 10-year peak depreciation of 38.18% between the two reference date extremes before recovering.

After the onset of the US credit crisis that accelerated in October 2008, the Peso had an exchange rate during October 1, 2008, through April 1, 2009 fluctuating from lowest to highest between $10.96 MXN per US$1.00 on October 1, 2008, to $15.42 MXN per US$1.00 on March 9, 2009, a peak depreciation ytd of 28.92% during those six months between the two reference date extremes before recovering.

From the $11.69 rate during 2004's low to the $15.42 rate during 2009's low, the peso depreciated 31.91% in that span covering the US recession coinciding Iraq War of 2003 and 2004 to the US & Global Credit Crisis of 2008.

Some experts including analysts at Goldman Sachs who coined the term BRIC in reference to the growing economies of Brazil, Russia, India, and China for marketing purposes believe that Mexico is going to be the 5th or 6th biggest economy in the world by the year 2050, behind China, United States, India, Brazil, and possibly Russia.

Monetary system

Mexico's monetary policy was revised following the 1994–95 financial crisis, when officials decided that maintaining general price stability was the best way to contribute to the sustained growth of employment and economic activity. As a result, Banco de México has as its primary objective maintaining stability in the purchasing power of the peso. It sets an inflation target, which requires it to establish corresponding quantitative targets for the growth of the monetary base and for the expansion of net domestic credit.

The central bank also monitors the evolution of several economic indicators, such as the exchange rate, differences between observed and projected inflation, the results of surveys on the public and specialists’ inflation expectations, revisions on collective employment contracts, producer prices, and the balances of the current and capital accounts.

A debate continues over whether Mexico should switch to a US-style interest rate-targeting system. Government officials in favor of a change say that the new system would give them more control over interest rates, which are becoming more important as consumer credit levels rise.

Until 2008, Mexico used a unique system, amongst the OECD countries, to control inflation in a mechanism known as the corto (lit. "shortage") a mechanism that allowed the central bank to influence market interest rates by leaving the banking system short of its daily demand for money by a predetermined amount. If the central bank wanted to push interest rates higher, it increased the corto. If it wished to lower interest rates, it decreased the corto. In April 2004, the Central Bank began setting a referential overnight interest rate as its monetary policy.

Business regulation

Corruption

Further information: Corruption in Mexico

Petty corruption based on exercise of administrative discretion in matters of zoning and business permits is endemic in Mexico adding about 10% to the cost of consumer goods and services. An April 2012 article in The New York Times reporting payment of bribes to officials throughout Mexico in order to obtain construction permits, information, and other favors resulted in investigations in both the United States and Mexico.

Using relatively recent night light data and electricity consumption in comparison with Gross County Product, the informal sector of the local economy in Veracruz state is shown to have grown during the period of the Fox Administration though the regional government remained PRI. The assumption that the informal economy of Mexico is a constant 30% of total economic activity is not supported at the local level. The small amount of local spatial autocorrelation that was found suggests a few clusters of high and low literacy rates amongst municipios in Veracruz but not enough to warrant including an I-statistic as a regressor. Global spatial autocorrelation is found especially literacy at the macro-regional level which is an area for further research beyond this study.

Improved literacy bolsters both the informal and formal economies in Veracruz indicating policies designed to further literacy are vital for growing the regional economy. While indigenous people are relatively poor, little evidence was found that the informal economy is a higher percentage of total economic activity in a municipio with a high share of indigenous people. While the formal economy might have been expanding relative to the informal economy in 2000, by 2006 this process had been reversed with growing informality. While rural municipios have smaller economies, they are not different than urban municipios in the share of the economy that is informal. Programs in the past that might move economic activity from the informal to the formal sector have not succeeded, suggesting public finance issues such as tax evasion will continue to plague the state with low government revenues.

Trade

| International trade | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| World Trade Center in Mexico City | ||

| Exports | US $248.8 billion f.o.b. (2006) | |

| Imports | US $253.1 billion f.o.b. (2006) | |

| Current account | ||

| Export partners | US 90.9%, Canada 2.2%, Spain 1.4%, Germany 1.3%, Colombia 0.9% (2006) | |

| Import partners | US 53.4%, China 8%, Japan 5.9% (2005) | |

Mexico is a trade-oriented economy, with imports and exports totaling a 78% share of the GDP in 2019. It is an important trade power as measured by the value of merchandise traded, and the country with the greatest number of free trade agreements. In 2020, Mexico was the world's eleventh largest merchandise exporter and thirteenth largest merchandise importer, representing 2.4% and 2.2% of world trade, respectively (and those rankings increased to 7th and 9th if the EU is considered a single trading entity). From 1991 to 2005, Mexican trade increased fivefold. Mexico is the biggest exporter and importer in Latin America; in 2020, Mexico alone exported US$417.7 billion, roughly equivalent to the sum of the exports of the next 5 largest exporters (Brazil, Chile, Argentina, Peru, and Colombia).

Mexican trade is fully integrated with that of its North American partners: as of 2019, approximately 80% of Mexican exports and 50% of its imports were traded with the United States and Canada. Nonetheless, NAFTA has not produced trade diversion. While trade with the United States increased 183% from 1993 to 2002, and that with Canada 165%, other trade agreements have shown even more impressive results: trade with Chile increased 285%, with Costa Rica 528% and Honduras 420%. Trade with the European Union increased 105% over the same time period.

Free trade agreements

Mexico joined the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1986, and today is an active and constructive participant of the World Trade Organization. Fox's administration promoted the establishment of a Free Trade Area of the Americas; Puebla served as temporary headquarters for the negotiations, and several other cities are now candidates for its permanent headquarters if the agreement is reached and implemented.

Mexico has signed 12 free trade agreements with 44 countries:

- The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) (1992) later United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) (2019) with the United States and Canada;

- Grupo de los tres, Group of the three , or G-3 (1994) with Colombia and Venezuela; the latter decided to terminate the agreement in 2006;

- Free Trade Agreement with Costa Rica (1994); superseded by the 2011 integrated Free Trade Agreement with the Central American countries;

- Free Trade Agreement with Bolivia (1994); terminated in 2010;

- Free Trade Agreement with Nicaragua (1997); superseded by the 2011 integrated Free Trade Agreement with the Central American countries;

- Free Trade Agreement with Chile (1998);

- Free Trade Agreement with the European Union (2000);

- Free Trade Agreement with Israel (2000);

- Northern Triangle Free Trade Agreement (2000), with Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras; superseded by the 2011 integrated Free Trade Agreement with the Central American countries;

- Free Trade Agreement with the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), integrated by Iceland, Norway, Liechtenstein and Switzerland (2001);

- Free Trade Agreement with Uruguay (2003);

- Free Trade Agreement with Japan (2004);

- Free Trade Agreement with Peru (2011);

- The integrated Free Trade Agreement with Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua (2011);

- Free Trade Agreement with Panama (2014); and

- The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) (2018).

Mexico has shown interest in becoming an associate member of Mercosur. The Mexican government has also started negotiations with South Korea, Singapore and Peru, and also wishes to start negotiations with Australia for a trade agreement between the two countries.

North American Trade Agreement and the USMCA Agreement

Main articles: North American Free Trade Agreement and USMCA

The 1994 North American Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is by far the most important Trade Agreement Mexico has signed both in the magnitude of reciprocal trade with its partners as well as in its scope. Unlike the rest of the Free Trade Agreements that Mexico has signed, NAFTA is more comprehensive in its scope and was complemented by the North American Agreement for Environmental Cooperation (NAAEC) and the North American Agreement on Labor Cooperation (NAALC). An updating of the 1994 NAFTA, the U.S., Mexico, Canada (USMCA) is pending in early 2020, awaiting the ratification by Canada; the U.S. and Mexico have ratified it.

The NAAEC agreement was a response to environmentalists' concerns that companies would relocate to Mexico or the United States would lower its standards if the three countries did not achieve a unanimous regulation on the environment. The NAAEC, in an aim to be more than a set of environmental regulations, established the North American Commission for Environmental Cooperation (NACEC), a mechanism for addressing trade and environmental issues, the North American Development Bank (NADBank) for assisting and financing investments in pollution reduction and the Border Environmental Cooperation Commission (BECC). The NADBank and the BECC have provided economic benefits to Mexico by financing 36 projects, mostly in the water sector. By complementing NAFTA with the NAAEC, it has been labeled the "greenest" trade agreement.

The NAALC supplement to NAFTA aimed to create a foundation for cooperation among the three members for the resolution of labor problems, as well as to promote greater cooperation among trade unions and social organizations in all three countries, in order to fight for the improvement of labor conditions. Though most economists agree that it is difficult to assess the direct impact of the NAALC, it is agreed that there has been a convergence of labor standards in North America. Given its limitations, however, NAALC has not produced (and in fact was not intended to achieve) convergence in employment, productivity and salary trend in North America.

The agreement fell short in liberalizing movement of people across the three countries. In a limited way, however, immigration of skilled Mexican and Canadian workers to the United States was permitted under the TN status. NAFTA allows for a wide list of professions, most of which require at least a bachelor's degree, for which a Mexican or a Canadian citizen can request TN status and temporarily immigrate to the United States. Unlike the visas available to other countries, TN status requires no sponsorship, but simply a job offer letter.

The overall benefits of NAFTA have been quantified by several economists, whose findings have been reported in several publications like the World Bank's Lessons from NAFTA for Latin America and the Caribbean, NAFTA's Impact on North America, and NAFTA revisited by the Institute for International Economics. They assess that NAFTA has been positive for Mexico, whose poverty rates have fallen, and real income salaries have risen even after accounting for the 1994–1995 economic crisis. Nonetheless, they also state that it has not been enough, or fast enough, to produce an economic convergence nor to reduce the poverty rates substantially or to promote higher rates of growth. Beside this the textile industry gain hype with this agreement and the textile industry in Mexico gained open access to the American market, promoting exports to the United States. The value of Mexican cotton and apparel exports to the U.S. grew from $3 billion in 1995 to $8.4 billion in 2002, a record high of $9.4 billion in 2000. At the same time, the share of Mexico's cotton textile market the U.S. has increased from 8 percent in 1995 to 13 percent in 2002. Some have suggested that in order to fully benefit from the agreement Mexico should invest in education and promote innovation as well as in infrastructure and agriculture.

Contrary to popular belief, the maquiladora program existed far before NAFTA, dating to 1965. A maquiladora manufacturer operates by importing raw materials into Mexico either tariff free (NAFTA) or at a reduced rate on a temporary basis (18 months) and then using Mexico's relatively less expensive labor costs to produce finished goods for export. Prior to NAFTA maquiladora companies importing raw materials from anywhere in the world were given preferential tariff rates by the Mexican government so long as the finished good was for export. The US, prior to NAFTA, allowed Maquiladora manufactured goods to be imported into the US with the tariff rate only being applied to the value of non US raw materials used to produce the good, thus reducing the tariff relative to other countries. NAFTA has eliminated all tariffs on goods between the two countries, but for the maquiladora industry significantly increased the tariff rates for goods sourced outside of NAFTA.

Given the overall size of trade between Mexico and the United States, there are remarkably few trade disputes, involving relatively small dollar amounts. These disputes are generally settled in WTO or NAFTA panels or through negotiations between the two countries. The most significant areas of friction involve trucking, sugar, high-fructose corn syrup, and a number of other agricultural products.

Mexican trade facilitation and competitiveness

A 2008 research brief published by the World Bank as part of its Trade Costs and Facilitation Project suggested that Mexico had the potential to substantially increase trade flows and economic growth through trade facilitation reform. The study examined the potential impacts of trade facilitation reforms in four areas: port efficiency, customs administration, information technology, and regulatory environment (including standards).

The study projected overall increments from domestic reforms to be on the order of $31.8 billion, equivalent to 22.4 percent of total Mexican manufacturing exports for 2000–03. On the imports side, the corresponding figures are $17.1 billion and 11.2 percent, respectively. Increases in exports, including textiles, would result primarily from improvements in port efficiency and the regulatory environment. Exports of transport equipment would be expected to increase by the greatest increment from improvements in port efficiency, whereas exports of food and machinery would largely be the result of improvements in the regulatory environment. On the imports side, Mexican improvements in port efficiency would appear to be the most important factor, although for imports of transport equipment, improvements in service sector infrastructure would also be of relative importance.

Major trade partners

The following table shows the largest trading partners for Mexico in 2021 by total trade value in billions of USD.

| Country | Trade Value | Import Value | Export Value | Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 609.67 | 221.31 | 388.36 | 167.05 | |

| 120.16 | 101.02 | 19.14 | -81.88 | |

| 37.93 | 11.22 | 26.71 | 15.49 | |

| 26.85 | 18.96 | 7.89 | -11.08 | |

| 26.50 | 17.21 | 9.29 | -7.93 | |

| 22.85 | 17.08 | 5.78 | -11.30 | |

| 13.49 | 8.72 | 4.77 | -3.95 | |

| 12.95 | 12.39 | 0.556 | -11.83 | |

| 10.10 | 4.58 | 5.52 | 0.935 | |

| 10.06 | 5.92 | 4.14 | -1.78 |

See also

- Small and medium enterprises in Mexico

- List of companies of Mexico

- List of largest Mexican companies

- List of hotels in Mexico

- List of Mexican brands

- Index of Mexico-related articles

- Mexico and the World Bank

- Poverty in Mexico

References

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Archived from the original on December 22, 2019. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on October 28, 2019. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ "The World Factbook". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects: October 2024". imf.org. International Monetary Fund.

- "Sistema de información económica, Banco de México". Archived from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ "EL CONEVAL PRESENTA LAS ESTIMACIONES DE POBREZA MULTIDIMENSIONAL 2022" (PDF). National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- "Poverty headcount ratio at $6.85 a day (2017 PPP) (% of population) - Mexico". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved March 21, 2024.

- "El Inegi da a conocer los resultados de la Encuesta Nacional de Ingresos y Gastos de los Hogares (ENIGH) 2022" (PDF). July 26, 2023. p. 15. Retrieved September 20, 2024.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/2024" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. March 13, 2024. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 13, 2024. Retrieved May 18, 2024.

- "Labor force, total - Mexico". www.inegi.org.mx. INEGI. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- "Employment to population ratio, 15+, total (%) (national estimate) - Mexico". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2020". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- "Employment and occupation". inegi.org.mx. National Institute of Statistics and Geography. January 2016. Archived from the original on November 29, 2019. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- "Home". Archived from the original on May 17, 2023. Retrieved May 14, 2023.

- "Taxing Wages 2023: Indexation of Labour Taxation and Benefits in OECD Countries | READ online". Archived from the original on September 7, 2023. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- "Home". Archived from the original on September 7, 2023. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ "Mexico: Economy, employment, equity, quality of life, education, health and public safety at Mexico". Secretariat of Economy. February 10, 2024. Archived from the original on December 7, 2023. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- "Sovereigns rating list". Standard & Poor's. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2013.

- ^ Rogers, Simon; Sedghi, Ami (April 15, 2011). "How Fitch, Moody's and S&P rate each country's credit rating". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on August 1, 2013. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- "Activos internacionales, crédito interno y bases monetarias". Banco de México. January 10, 2024. Archived from the original on January 11, 2024. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- Moreno-Brid, Juan Carlos; Ros, Jaime (2009). Development and Growth in the Mexican Economy: A Historical Perspective. Oxford University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-199-70785-0.