| Lion dance | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A Southern Chinese lion dance in Chinatown, Manhattan, New York City A Southern Chinese lion dance in Chinatown, Manhattan, New York City | |||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 舞獅 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 舞狮 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 跳獅 or 弄獅 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | múa lân (sư - rồng) | ||||||||||

| Chữ Nôm | 𢱖麟(獅蠬) | ||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||

| Hangul | 사자춤 | ||||||||||

| Hanja | 獅子춤 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||

| Kanji | 獅子舞 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Indonesian name | |||||||||||

| Indonesian | barongsai | ||||||||||

Lion dance (traditional Chinese: 舞獅; simplified Chinese: 舞狮; pinyin: wǔshī) is a form of traditional dance in Chinese culture and other Asian countries in which performers mimic a lion's movements in a lion costume to bring good luck and fortune. The lion dance is usually performed during the Chinese New Year and other traditional, cultural and religious festivals. It may also be performed at important occasions such as business opening events, special celebrations or wedding ceremonies, or may be used to honour special guests by the Chinese communities.

The Chinese lion dance is normally operated by two dancers, one of whom manipulates the head while the other manipulates the tail of the lion. It is distinguishable from the dragon dance which is performed by many people who hold the long sinuous body of the dragon on poles. The fundamental movements of the Lion dance can be found in Chinese martial arts, and it is commonly performed to a vigorous drumbeat with gongs and cymbals.

There are two main forms of the Lion dance, the Northern Lion and the Southern Lion. Both forms are commonly found around the world especially in Southeast Asia, the Southern Lion predominates as it was spread by the Chinese diaspora communities who are historically mostly of Southern Chinese origin. Versions of lion dance related to the Chinese lion are also found in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam. Besides the Chinese-based lion dance, other forms of lion dance also exist in India, Indonesia, and East Africa.

History

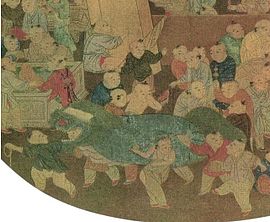

There has been an old tradition in China of dancers wearing masks to resemble animals or mythical beasts since antiquity, and performances described in ancient texts such as Shujing where wild beasts and phoenix danced may have been masked dances. In Qin dynasty sources, dancers performing exorcism rituals were described as wearing bearskin mask, and it was also mentioned in Han dynasty texts that "mime people" (象人) performed as fish, dragons, and phoenixes. However, lion is not native to China (a species found in Northeast China Panthera youngi had long become extinct), and the Lion Dance therefore has been suggested to have originated outside of China from countries such as India or Persia, and introduced via Central Asia. According to ethnomusicologist Laurence Picken, the Chinese word for lion itself, shi (獅, written as 師 in the early periods), may have been derived from the Persian word šer. The earliest use of the word shizi meaning lion first appeared in Han dynasty texts and had strong association with Central Asia (an even earlier but obsolete term for lion was suanni (狻麑 or 狻猊), and lions were presented to the Han court by emissaries from Central Asia and the Parthian Empire. Detailed descriptions of Lion Dance appeared during the Tang dynasty and it was already recognized by writers and poets then as a foreign dance, however, Lion dance may have been recorded in China as early as the third century AD where "lion acts" were referred to by a Three Kingdoms scholar Meng Kang (孟康) in a commentary on Hanshu. In the early periods it had association with Buddhism: it was recorded in a Northern Wei text, Description of Buddhist Temples in Luoyang (洛陽伽藍記), that a parade for a statue of Buddha of a temple was led by a lion to drive away evil spirits. An alternative suggestion is therefore that the dance may have developed from a local Chinese tradition that appropriated the Buddhist symbolism of lion.

There were different versions of the dance in the Tang dynasty. In the Tang court, the lion dance was called the Great Peace Music (太平樂, Taiping yue) or the Lion Dance of the Five Directions (五方師子舞) where five large lions of different colours and expressing different moods were each led and manipulated on rope by two persons, and accompanied by 140 singers. In another account, the 5 lions were described as each over 3 metres tall and each had 12 "lion lads", who may tease the lions with red whisks. Another version of the lion dance was described by the Tang poet Bai Juyi in his poem "Western Liang Arts" (西凉伎), where the dance was performed by two hu (胡, meaning here non-Han people from Central Asia) dancers who wore a lion costume made of a wooden head, a silk tail and furry body, with eyes gilded with gold and teeth plated with silver as well as ears that moved, a form that resembles today's Lion Dance. By the eighth century, this lion dance had reached Japan. During the Song dynasty the lion dance was commonly performed in festivals and it was known as the Northern Lion during the Southern Song.

The Southern Lion is a later development in the south of China originating in the Guangdong province. There are a number of myths associated with the origin of the Southern Lion: one story relates that the dance originated as a celebration in a village where a mythical monster called Nian was successfully driven away; another has it that the Qianlong Emperor dreamt of an auspicious animal while on a tour of Southern China, and ordered that the image of the animal be recreated and used during festivals. However it is likely that the Southern Lion of Guangzhou is an adaptation of the Northern Lion to local myths and characteristics, perhaps during the Ming dynasty.

Regional types

The two main types of lion dance in China are the Northern and Southern Lions. There are however also a number of local forms of lion dance in different regions of China, and some of these lions may have significant differences in appearance, for example the Green or Hokkien Lion (青獅, Qing Shi) and the Taiwanese or Yutien Lion (明獅, Ming Shi), popular with the Hokkien and the Taiwanese people. Other ethnic minorities groups in China also have their own lion dances, for example, the lion dance of the Muslim minority in Shenqiu County in Henan called the Wen Lion, the Yongdeng lion dance in Yongdeng County, Lanzhou, Gansu, the lion dance in Yongning County, and Wuzhong, Ningxia, and the Hakka Lion – popular with the Hakka people, which is very similar to both the Hokkien and Taiwanese Lions and even the Wen Lion, but the Hakka lion may or may not have a horn on its head. Chinese lion dances usually involve two dancers but may also be performed by one. The larger lions manipulated by two persons may be referred to as great lions (太獅), and those manipulated by one person little lions (少獅). The performances may also be broadly divided into civil (文獅) and martial (武獅) styles. The civil style emphasizes the character and mimics and behaviour of the lion, while the martial style is focused on acrobatics and energetic movements.

There are related forms of dances with mask figures that represent mythical creatures such as the Qilin and the Pixiu. The Qilin dance and the Pixiu dance are also most commonly performed by the Hakka people who were originally from the Central China, but have largely settled in the south of China and southeast Asia in modern times.

Various forms of lion dance are also found widely in East Asian countries such as Japan, Korea, Vietnam, as well as among the communities in the Himalayan region.

Chinese Northern Lion

The Chinese Northern Lion (simplified Chinese: 北狮; traditional Chinese: 北獅; pinyin: Běi shī) Dance is often performed as a pair of male and female lions in the north of China. Northern lions may have a gold-painted wooden head, and shaggy red and yellow hair with a red bow on its head to indicate a male lion, or a green bow (sometimes green hair) to represent a female. There are however regional variations of the lion.

It is said that the northern lion may have originated from Northern Wei, when Hu dancers performed the dance for the emperor, and it was referred to as Northern Lion by the Song dynasty.

Northern lions resemble Pekingese or Foo Dogs/Fu Dogs, and their movements are lifelike during a performance. Acrobatics is very common, with stunts like lifts, or balancing on a tiered platform or on a giant ball. Northern lions sometimes appear as a family, with two large "adult" lions and a pair of small "young" lions. There are usually two performers in one adult lion, and one in the young lion. There may also be a "warrior" character who holds a spherical object and leads the lions.

The dance of the Northern Lion is generally more playful than the Southern Lion. Regions with well-known lion dance troupes include Ninghai in Ningbo, Xushui in Hebei province, Dalian in Liaoning province, and Beijing. There are a number of variations of the lion dance performance, for example the Heavenly Tower Lion Dance (simplified Chinese: 天塔狮舞; traditional Chinese: 天塔獅舞; pinyin: Tiān tǎ shī wǔ) from Xiangfen County in Shanxi is a performance whereby a number of lions climb up a tall tower structure constructed out of wooden stools, and there are also high-wire acts involving lions

Chinese Southern Lion

The Chinese Southern Lion (simplified Chinese: 南狮; traditional Chinese: 南獅; pinyin: Nán shī) or Cantonese Lion dance originated from Guangdong and is the best known lion outside of China. The Southern Lion has a single horn, and is associated with the legend of a mythical monster called Nian. The lion's head is traditionally constructed using papier-mâché over a bamboo frame covered with gauze, then painted and decorated with fur. Its body is made of durable layered cloth also trimmed with fur. Newer lions, however, may be made with modern materials such as aluminium instead of bamboo and are lighter. Newer versions may also apply shinier modern material over the traditional lacquer such as sequin or laser sticker, but they do not last as long as those with lacquer. Different types of fur may be used in modern lions.

There are two main styles of Southern Lion: the Fut San or Fo Shan (Chinese: 佛山; pinyin: Fóshān; lit. 'Buddha Mountain'), and the Hok San or He Shan (simplified Chinese: 鹤山; traditional Chinese: 鶴山; pinyin: Hèshān; lit. 'Crane Mountain'), both named after their place of origin. Other minor styles include the Fut-Hok (a hybrid of Fut San and Hok San created in Singapore by Kong Chow Wui Koon in the 1960s), and the Jow Ga (performed by practitioners of Jow family style kung fu). The different lion types can be identified from the design of the lion head.

Fo Shan is the style adopted by many kung fu schools. It uses kung fu moves and postures to help with its movements and stances, and only the most advanced students are allowed to perform. Traditionally, the Fo Shan lion has bristles instead of fur, and is heavier than the modern ones now popularly used. All traditional Fo Shan lions have pop-up teeth, tongue, and eyes that swivel left and right. On the back are gold-foiled rims and a gilded collar where the troupe's name may be sewn on. It has a very long tail with a white underside, and is often attached with bells. The designs of the tail are also more square and contain a diamond pattern going down the back. It has a high forehead, curved lips and a sharp horn on its head. Traditional Fo Shan lions are ornate in appearance, a number of regional styles however have developed around the world. The newer styles of Fo Shan lions replace all the bristles with fur and the tails are shorter. The eyes are fixed in place, and the tongue and teeth do not pop up. The tail is curvier in design, does not have a diamond pattern, and lacks bells.

The He Shan style lion is known for its richness of expression, unique footwork, impressive-looking appearance and vigorous drumming style. The founder of this style is the "Canton Lion King" Feng Gengzhang (simplified Chinese: 冯庚长; traditional Chinese: 馮庚長; pinyin: Féng Gēngzhǎng) in the early 20th century. Feng was born in a village in He Shan county in Guangdong where he was instructed in martial arts and lion dance by his father. Later, he also studied martial arts and lion dance in Foshan before returning to his hometown and setting up his own training hall. He developed his version of lion dance, introducing new techniques by studying and mimicking the movement of cats, such as "catching mouse, playing, catching birds, high escape, lying low and rolling". He and his disciples also made changes to the lion head; its forehead is lower, its horn rounded and it has a duck beak mouth with flat lips, the body also has more eye-catching colours. Together with new dance steps and footwork, a unique rhythm invented by Feng called the "Seven Star Drum", Feng created a new style of lion dancing that is high in entertainment value and visual appeal. In the early 1920s, the He Shan lion dance was performed when Sun Yat-Sen assumed office in Guangzhou, creating a stir. The He Shan lion performers were invited to perform in many places within China and Southeast Asia during celebratory festivals. The style became very popular in Singapore; the He Shan lion acquired the title of "Lion King of Kings", with a "king" character (王) added on its forehead. The Singapore Hok San Association made further changes by modifying the design of the lion head, shortening its body, and creating a new drumbeat for the dance.

Different colors are used to signify the age and character of the lions. The lion with white fur is considered to be the oldest of the lions, while the lion with golden yellow fur is the middle child. The black lion is considered the youngest lion, and the movement of this lion should be fast like a young child or a headstrong teenager. The colors may also represent the character of the lion: the golden lion represents liveliness, the red lion courage, and the green lion friendship. There are also three lion types that represent three historical characters in the classic Romance of the Three Kingdoms who were blood oath brothers sworn to restore the Han dynasty:

- The Liu Bei (Cantonese: Lau Pei) lion is the eldest of the three brothers and has a yellow (actually imperial yellow as he became the first emperor of the Shu-Han Kingdom) based face with a white beard and fur (to denote his wisdom). It sports a multicolored tail signifying the colors of the five elements. There are three coins on the collar. This lion is used by schools with an established Martial art master (Sifu) or organization and is known as the Rui Shi (simplified Chinese: 瑞狮; traditional Chinese: 瑞獅; pinyin: Ruì Shī; lit. 'Auspicious Lion').

- The Guan Gong (Cantonese: Kwan Kung) lion has a red based face, black bristles, with a long black beard (as he was also known as the "Duke with the Beautiful Beard"). The tail is red and trimmed with black. He is known as the second brother and sports two coins on the collar. This Lion is known as the Xing Shi (simplified Chinese: 醒狮; traditional Chinese: 醒獅; pinyin: Xǐng Shī; lit. 'Awakened Lion').

- The Zhang Fei (Cantonese: Cheung Fei) lion has a black based face with short black beard, small ears, and black bristles. The tail is black and white. Traditionally this lion also had bells attached to the body. Being the youngest of the three brothers, there is only a single coin on the collar. This Lion is known as the Dou Shi (simplified Chinese: 斗狮; traditional Chinese: 鬥獅; pinyin: Dòu Shī; lit. 'Fighting Lion') because Zhang Fei had a quick temper and loved to fight. This lion is used by clubs that were just starting out or by those wishing to make a challenge.

Later three more Lions were added to the group. The green-faced lion represented Zhao Yun or Zhao (Cantonese: Chiu) Zi Long. The green lion has a green tail, black beard and fur, and an iron horn. Often called the fourth brother, this lion is also called the Heroic Lion because Zhao was said to ride through Cao Cao's million man army to rescue Liu Bei's infant and fight his way back out. The yellow lion has yellow/orange face and body with white or silver beard and fur, representing Huang Zhong (Cantonese: Wong Tsung), who was given this color when Liu Bei rose to become Emperor. This lion is called the Righteous Lion. The white lion is known as Ma Chao (Cantonese: Ma Chiu), he was assigned this color because he always wore a white armband in his battle against the ruler of Wei, Cao Cao, to signify that he was in mourning for his father and brother who had been murdered by Cao Cao. This lion is therefore also known as the funeral lion, and is never used except for the funeral of a Master or an important head of a group. In such cases the lion is usually burned right after use as it is considered symbolically inauspicious or ill-fated to be kept around. This lion is sometimes confused with the silver lion which sometimes has a whitish colouring. These three along with Guan Yu and Zhang Fei were known as the "Five Tiger Generals of Shun," each representing one of the colors of the five elements.

Green Lion

Green Lion (青狮) is the lion dance form associated with the Hokkien-speaking people of Fujian and Taiwan. It is similar to the Chinese southern lion dance, except that the lion is mainly green in color and has a distinct round flat mask. It is believed to have originated in the anti-Manchu movements after the fall of the Ming dynasty in 1644. The word "green lion" in the Hokkien language sounds similar to "Qing army" (清师). During training sessions for fighters, the Green lion was fitted with blades symbolizing the Manchurian army and would become a moving target for trainees. It is said that after the fall of Qing dynasty in 1912, martial arts expert Gan De Yuan (干德源) organized a performance in Quanzhou where the Green Lion was dismembered to represent the overthrow of the Qing dynasty. From that point onwards, the Green Lion is used without the blades and performed for cultural and ritual purposes.

Qilin Dance

A related form of dance is the Qilin or Kirin dance, which is traditionally performed by the Hakka people. The Qilin is a mythical creature believed to symbolize good fortune, prosperity, and harmony, and performers wear ornate Qilin costumes with vibrant colors and intricate details to resemble the mythical creature. The Qilin costume features a single horn in the middle, with finned ridges lined with fur. The dance involves graceful and synchronized movements that mimic cats and tigers. The performance routine typically tells of a Qilin exiting its lair, playfully move round, and looking for vegetable to eat. After eating from the vegetable, it spits it out, and it also spits a jade book, before moving around and returning back to its lair. The dance is accompanied by music played on traditional Chinese instruments, including drums, flutes, and cymbals. Today, similar to the Chinese Lion and Dragon dances, the Qilin dance is commonly performed during important Chinese celebrations and festivals, such as Chinese New Year and weddings, it is also performed to preserve cultural traditions and enhance community cohesion.

Vietnamese Lion

The lion dance may be known in Vietnam as the qilin dance (Vietnamese: múa lân or múa sư tử) based on the mythical creature kỳ lân, which is similar to the Chinese Qilin. Most lions in Vietnam resemble the Southern Lion, specifically Fut San style – they are part of the Chinese Southern Lion tradition but have acquired local characteristics with differences in appearance. In the past, costumes more similar to the Qilin were used, but today, many troupes buy lion costumes from China, unaware of the subtle differences that set the Lion Dance and Qilin Dance apart. There are nevertheless distinct local forms that differ significantly in appearance and performance, for example the lion dances of the Tày and Nùng minority people. A court version of the dance is performed at the Duyet Thi Duong Theatre within the ground of the royal palace in Huế.

The dance is performed primarily at traditional festivals such as Tết Nguyên Đán and Tết Trung Thu, as well as during other occasions such as the opening of a new business, birthdays, and weddings. The dance is typically accompanied by martial artists and acrobatics. A feature of the Vietnamese lion dance is its dance partner Ông Địa or the god of the earth, depicted as a large-bellied, broadly grinning man holding a palm-leaf fan similar to the Chinese 'Big Head Buddha' (大头佛). The good-hearted god, according to popular beliefs, has the power to summon the auspicious kỳ lân, and thus during the dance, takes the lead in clearing the path for the kỳ lân.

Japanese Lion

Japan has a long tradition of the lion dance and the dance is known as shishi-mai (獅子舞) in Japanese. It is thought to have been imported from China during the Tang dynasty, and became associated with the celebration of Buddha's Birthday. The first lion dance recorded in Japan was at the inauguration ceremonies of Tōdai-ji in Nara in 752. The oldest surviving lion mask, made of paulownia wood with an articulated lower jaw, is also preserved in Tōdai-ji. The dance is commonly performed during the New Year to bring good luck and drive away evil spirits, and the lion dancers may be accompanied by flute and drum musicians. It is also performed at other festivals and celebrations. In some of these performances, the lions may bite people on the head to bring good luck.

The lion dance has been completely absorbed into Japanese tradition. There are many different lion dances in Japan and the style of dancing and design of the lion may differ by region – it is believed that as many as 9,000 variations of the dance exist in the country. The lion dance is also used in religious Shinto festivals as part of a performing art form called kagura. Shishi kagura may be found in different forms – for example the daikagura which is mainly acrobatic, the yamabushi kagura, a type of theatrical performance done by yamabushi ascetics, and also in bangaku and others. Various forms of shishi dances are also found in noh, kabuki (where the lion dances form a group of plays termed shakkyōmono, examples include Renjishi), and bunraku theatres.

The Japanese lion usually consists of a wooden, lacquered head called a shishi-gashira (lit. Lion Head), often with a characteristic body of green dyed cloth with white designs. It can be manipulated by a single person, or by two or more persons, one of whom manipulates the head. The one-man variety is most often seen in eastern Japan. As with Chinese lions, the make of the head and designs on the body will differ from region to region, and even from school to school. The mask however may sometimes have horns appearing to be a deer (shika), and shishi written with different Kanji characters can mean beast, deer or wild boar, for example as in shishi-odori (鹿踊, lit. Deer Dance). Historically the word shishi may refer to any wild four-legged animal, and some of these dances with different beasts may therefore also be referred to as shishi-mai. The dance may also sometimes feature tigers (tora) or qilin (kirin).

In Okinawa, a similar dance exists, though the lion there is considered to be a legendary shisa. The heads, bodies and behavior of the shisa in the dance are quite different from the shishi on mainland Japan. Instead of dancing to the sounds of flutes and drums, the Okinawan shisa dance is often performed to folk songs played with the sanshin.

Korean Lion

Lion dance was recorded in the Korean historical work Samguk Sagi as "Sanye" (狻猊, the old word for lion), one of the five poems on the dances of the Silla kingdom written by Ch'oe Ch'i-wŏn. It may have been recorded as early as the King Jinheung's reign in the 6th century during which a tune titled "The Lion's Talent" was composed that could be a reference to a lion dance. Two main traditions of lion dance survive in Korea, the saja-noreum, which is performed as an exorcism drama; and the sajach'um which is performed in association with masked dramas. In many of the traditional masked dance dramas, the lion dance appears as one part of a number of acts. Examples of these dramas are Ŭnyul t'alch'um, Pongsan t'alch'um (봉산탈춤), Suyong Yayu (수영야류), and T'ongyong Ogwangdae (통영오광대). There was also once a court version of the lion dance.

Lion dance as an exorcism ritual began to be performed in the New Year in Korea during the Goryeo dynasty. The best known of the Korean saja-noreum lion dances is the Bukcheong sajanoreum or lion mask play from Bukcheong. In this lion dance the lion with a large but comic lion mask and brown costume may be performed together with performers wearing other masks. The dancers may be accompanied by musicians playing a double-headed drum, an hourglass-shaped drum, a large gong, and a six-holed bamboo flute. The dance was originally performed every night of the first fifteen nights of the Lunar New Year, where the dance troupe in lion masks and costumes visited every house in the villages of the Bukcheong region, and the lion dance is meant to expel evil spirits and attract good luck for the coming year. The eyes of the lion mask may be painted gold to expel negative spirits. The lion masks of Pongsan and Gangnyeong may feature rolling eyes and bells meant to frighten demons when they make a sound as the lion moves. It is also believed that children who sat on the back of the lion during such performances would enjoy good health and a long life.

Tibetan Lion

In the Himalayan and Tibetan area, there is also a lion dance called the snow lion dance. This dance may be found in Tibet and also among Tibetan diaspora communities where it is called Senggeh Garcham, Nepal, Bhutan, and parts of Northeastern India – among the Monpa people in Arunachal Pradesh, in Sikkim where it is called Singhi Chham, and in some parts of Uttar Pradesh and Ladakh. The name seng ge and its related forms come from Sanskrit for lion, siṅha, and cham is a Buddhist ritual dance. The snow lion has white fur, and in Tibet, it may also have a green mane or green fringes, while in Sikkim, the mane may be blue.

The Snow Lion is regarded as an emblem of Tibet and the Snow Lion Dance is a popular dance in Tibetan communities and it is performed during festivals such as during the ritual dance (cham) festival and the New Year. The snow lion represents the snowy mountain ranges and glaciers of Tibet and is considered highly auspicious, and it may also symbolize a number of characteristics, such as power and strength, and fearlessness and joy. Some local versions of the snow lion dance may also have been influenced by Chinese Lion Dance in the Sino-Tibetan borderland – for example, it was recorded that the local chief in Songpan, Sichuan gave a lion costume to the Jamyang Zhépa II of the Amdo region in the 18th century. The snow lion dance may be performed as a secular dance, or as a ritual dance performed by bon po monks.

India

Excluding the snow lion dances found in the Himalayan regions, lion costumes may be used in various forms of dances in other parts of India. In West Bengal's Purulia district, a version of the Chhau dance is the only one to incorporate lion costumes. In this dance, the lions are associated with the Hindu goddess Durga as her mount. The lion Chhau masks are made of papier-mâché with dried grass as fur.

In Songi Mukhawate or Songi Mukhota dance, a masked folk dance from Maharastra performed during Chaitra Purnima, Navaratri, and other special occasions, the lion costumes may also be use. The lion costumes represent Narasimha.

In Honnavar Taluk in Uttara Kannada, a lion dance called simha nrutya may be performed in Yakshagana plays. The dancers wear a cotton mask that resembles a lion with two silver fangs, and they dance in imitation of the movements and behaviour of lion.

Indonesia

Main articles: Reog, Barong dance, and Sisingaan

The Chinese lion dance is referred to as barongsai in Indonesia, often performed by Chinese Indonesian during Imlek. Indonesians however, have developed their own style of lion dances. The lion dance (Indonesian: barong) in Indonesia has different forms that are distinct to the local cultures in Indonesia, and it is not known if these have any relation to the Chinese lion. The best known lion dances are performed in Bali and Java.

In Hindu Balinese culture, the Barong is the king of good spirits and the enemy of the demon queen Rangda. Like the Chinese lion, it requires more dancers than in the Javanese Reog, typically involving two dancers.

The Reog dance of Ponorogo in Java involves a lion figure known as the singa barong. It is held on special occasions such as the Lebaran (Eid al-Fitr), City or Regency anniversary, or Independence day carnival. A single dancer, or warok, carries the heavy lion mask about 30–40 kg weight by his teeth. He is credited with exceptional strength. The warok may also carry an adolescent boy or girl on its head. When holding an adolescent boy or girl on his head, the Reog dancer holds the weight up to total 100 kilograms. The great mask that spans over 2.5 meters with genuine tiger or leopard skin and real peacock feathers. It has gained international recognition as the world's largest mask.

Another form of Indonesian lion dance is called Sisingaan from West Java. Sisingaan marked by a form of a lion-shaped effigy palanquin that is carried by a group of dancers who perform various attractions accompanied by traditional music. Thus lion palanquin is being ride by a children, and usually performed to celebrate the circumcision ceremony, where the child is carried on a lion around the kampung (village).

East Africa

Around the world there are lion dances that are local to their area and unrelated to the Chinese dance. For example, various tribes in East Africa, such as the Maasai and Samburu people of Kenya, used to perform a lion dance to celebrate a successful lion hunt, considered by these tribes to be a prestigious act and a sign of bravery. The dancers may also reenact a lion hunt. Some of them make a headdress out of the mane of the slain lion (or out of other animals) and wear the headdress in the dance. Young men may also wear the lion-mane headdress and dance in a coming-of-age ceremony. However, as lion-hunting has been made illegal, the dance is seldom performed in a real scenario nowadays, but they may continue to perform the dance for tourists.

Music and instruments

Problems playing this file? See media help.

The Chinese Lion Dance is performed accompanied by the music of beating of tanggu (drum) (in Singapore, datanggu), cymbals, and gongs. Instruments synchronize to the lion dance movements and actions. Fut San, Hok San, Fut Hok, Chow Gar, etc. all play their beat differently. Each style plays a unique beat. Developments in electronic devices have allowed music to be played via phone/tablet/computer/mp3 player. This has contributed to the evolution of how people can play lion dance music – which eliminates the need to carry around instruments (which can be quite large).

The most common style is Sar Ping lion dance beats. This has more than 22 different testings that one can use to show the lion's movement, whereas fut san has only around 7.

Costumes

The lion dance costumes used in these performances can only be custom made in specialty craft shops in rural parts of Asia and have to be imported at considerable expense for most foreign countries outside Asia. For groups in Western countries, this is made possible through funds raised through subscriptions and pledges made by members of local cultural and business societies. For countries like Malaysia with a substantial Chinese population, local expertise may be available in making the lion costumes and musical instruments without having to import them from China. Most modern Southern Lion dance costumes come with a set of matching pants, however some practitioners use black kung fu pants to appear more traditional. Modern lion dance costumes are made to be very durable and some are waterproof.

Association with Wushu/Kung Fu

The Chinese lion dance has close relations to kung fu or Wǔshù (武術) and the dancers are usually martial art members of the local kung fu club or school. They practice in their club and some train hard to master the skill as one of the disciplines of the martial art. In general, it is seen that if a school has a capable troupe with many 'lions', it demonstrates the success of the school. It is also generally practised together with Dragon dance in some area.

During Chinese New Years and festivals

During the Chinese New Year, lion dance troupes will visit the houses and shops of the Asian community to perform the traditional custom of "cai qing" (採青), literally meaning "plucking the greens", whereby the lion plucks the auspicious green lettuce either hung on a pole or placed on a table in front of the premises. The "greens" (qing) are tied together with a "red envelope" containing money and may also include auspicious fruit like oranges. In Chinese, cǎi (採, pluck) also sounds like cài (菜, meaning vegetable) and cái (财, meaning fortune). The lion will dance and approach the "greens" and "red envelope" like a curious cat, to "eat the green" and "spit" it out. In the process, they will keep the "red envelope", which is the reward for the lion troupe. The lion dance is believed to bring good luck and fortune to any business that receives one. During the Qing dynasty, there may be additional hidden meanings in the performances. For example, the green vegetables (qing) eaten by the lion may represent the Qing Manchus. The lion dance troupes are sometimes accompanied by various characters such as the Big Head Buddha.

Different types of vegetables, fruits, foods, or utensils with auspicious and good symbolic meanings; for instance pineapples, pomelos, bananas, oranges, sugar cane shoots, coconuts, beer, clay pots or even crabs can be used as the "greens" (青) to be "plucked". They can also be used to give a varying difficulty for the performers or outright challenge them. Usually, more difficult challenges come with the bigger rewards inside the "red envelope" given.

In the old days, the lettuce was hung 5–6 m (16–20 ft) above ground; only well-trained martial artists could reach the money while dancing with the heavy lion head. These events became a public challenge. A large sum of money was rewarded, and the audience expected a good show. Sometimes, if lions from multiple martial arts schools approached the lettuce at the same time, the lions were supposed to fight to decide a winner. The lions had to fight with stylistic lion moves instead of chaotic street fighting styles. The audience would judge the quality of the martial art schools according to how the lions fought. Since the schools' reputations were at stake, the fights were usually fierce but civilized. The winner lion would then use creative methods and martial art skills to reach the high-hanging reward. Some lions may dance on bamboo stilts and some may step on human pyramids formed by fellow students of the school. The performers and the schools would gain praise and respect on top of the large monetary reward when they did well.

During the 1950s-60s, in some areas with high populations of Chinese and Asian communities (especially the Chinatown in many foreign countries outside of China), people who joined lion dance troupes were "gangster-like". This caused a lot of fighting between lion dance troupes and kung fu schools. Parents were afraid to let their children join lion dance troupes because of the "gangster" association with the members. During festivals and performances, when lion dance troupes met, there may be fights between groups. Some lifts and acrobatic tricks are designed for the lion to "fight" and knock over other rival lions. Performers even hid daggers in their shoes and clothes, which could be used to injure other lion dancers’ legs. Some others even attached a metal horn on their lion’s forehead, which could be used to slash other lion heads. The violence became so extreme that at one point, the Hong Kong government banned lion dance completely. Now, as with many other countries, lion dance troupes must attain a permit from the government in order to perform lion dance. Although there is still a certain degree of competitiveness, troupes are a lot less violent and aggressive. Nowadays, whenever teams meet each other, they'll shake hands through the mouth of the lion to show sportsmanship.

In a traditional performance, when the dancing lion enters a village or township, it is supposed to pay its respects first at the local temple(s), then to the ancestors at the ancestral hall, and finally throughout the streets to bring happiness to all the people.

Evolution and competition

Lion dance has spread across the world due to the worldwide presence of the diaspora Chinese communities and immigrant settlers in many countries in the Americas, Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, Pacific Polynesia, and in particular, in Southeast Asia where there is a large overseas Chinese presence.

The dance has evolved considerably since the early days when it was performed as a skill part of Chinese martial arts, and has grown into a more artistic art and a sport as well that takes into accounts the lion's expression and the natural movements, as well as the development of a more elaborate acrobatic styles and skills during performances. This evolution and development has produced the modern form of lion dances, and competitions are held to find the best lion dance performances.

International lion dance championships are held in many countries, for example in Malaysia, Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan. The competition mostly involves Southern Lion dance teams and may be performed on a series of small circular platforms raised on poles called jongs, and there are a total of 21 or even 22 poles in the traditional set. These poles ranged from 4 to 10 feet (1 to 3 m) in height, but championship poles can go up to 20 to 26 feet (6 to 8 m). The poles can be added with props or obstacles as well, such as a small wooden bridge that can be easily broken in half, or a pair of wire lines that can be crossed over. The first jongs built were introduced in 1983 for a competition in Malaysia, made out of wood with a small circular rubber platform on top and an iron fitting on the bottom, with a total of 5 poles in the original set called the "May Hua Poles" Or "Plum Blossom Poles", which were 33 inches in height and 8 inches in width. Later, 16 or even 17 poles were added in the set, but all 21 or even 22 poles were 85.11 inches higher and 6 inches wider, and are made out of iron instead. The competition is judged based on the skill and liveliness of the lion together with the creativity of the stunts and choreographed moves, as well as the difficulty of the acrobatics, and rhythmic and pulsating live instrumental accompaniment that can captivate the spectators and the judges of the competition. The main judging rubric was developed by the International Dragon and Lion Dance Federation, scored out of 10 total points. Their rubric is used in many professional competitions including Genting, Malaysia, which is recently held at Arena of Stars since it was opened in 1998. The Genting World and National Lion Dance Championships are held every two years in Malaysia, starting in the 1980s. The champion as of 2018 is consecutive winner Kun Seng Keng from Muar, Johor, Malaysia, winners of 11 out of the 13 Genting competitions, as well as other competitors from Malaysia such as Gor Chor from Segamat, Johor, Malaysia, Hong Teik from Alor Setar, Kedah, Malaysia, Khuan Loke from Sungai Way, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia, and Guang Yi Kwong Ngai from Seri Kembangan, Selangor, on the outskirts in the capital Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. By 2001 and 2002, dragon dance teams are also involved in competitions at Genting as well. Another famous competition event held in Malaysia was the Tang Long Imperial World Dragon and Lion Dance Championship at Putra Indoor Stadium, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia in 2002. It also involves both Northern and Southern Lion dance teams, but dragon dance teams as well. Another competition called the Ngee Ann City National Lion Dance Championships are held every year in Ngee Ann City, Orchard Road, Singapore, starting in the 1990s.

In politics

The lion dance is seen as a representative part of Chinese culture in many overseas Chinese communities, and in some Southeast Asian countries, there were attempts to ban or discourage the dance in order to suppress the Chinese cultural identity in those countries. For example, in Malaysia, lion dance was criticized by a Malay politician in the 1970s as not Malaysian in style and suggested that it be changed to a tiger dance, and it was banned except at Chinese New Year until 1990. Lion dance became a matter of political and public debate about the national culture of the country. During the Suharto era in Indonesia, public expression of Chinese culture was also banned and barongsai (lion dance) procession was considered "provocative" and "an affront to Indonesian nationalism". This ban was however overturned after the collapse of the Suharto regime in 1998, nevertheless the occasional local banning of the lion dance still occurred.

In popular culture

In the 1960s and 1970s, during the era when the Hong Kong's Chinese classic and martial arts movies are very popular, kung fu movies including Jet Li's Wong Fei Hung has actually indirectly shows and indicates how lion dance was practiced with the kung fu close co-relation and kung fu during that time, e.g. Dreadnaught and Martial Club. In those days the lion dance was mostly practised and performed as Wushu or kung fu skills, with the challenge for the 'lion' built of chairs and tables stacked up together for the 'lion' to perform its stunts and accomplish its challenge.

In the 1976 musical, Pacific Overtures by Stephen Sondheim, the first act ends with a musical number titled "Lion dance". The Commodore Perry character performed a mixture of a kabuki version of lion dance and a cakewalk wearing an Uncle Sam costume and the long white wig and makeup of a kabuki lion, here used to express his feelings of success at having met with Japanese officials and opened Japan to trade for the first time in 250 years. The kabuki lion dance also appeared in the 1957 film Sayonara with Ricardo Montalbán.

Several 1990s movies, including a remade version of Wong Fei Hung, and the sequels of Once Upon a Time in China, involve plots centered on lion dancing, especially Once Upon a Time in China III and IV. The series' main actor, Jet Li, has performed as a lion dancer in several of his films, including Northern style lion dancing in Shaolin Temple, Shaolin Temple 2: Kids from Shaolin, Shaolin Temple 3: North and South Shaolin and Southern style lion dancing in Once Upon a Time in China III and Once Upon a Time in China and America.

Other films include The Young Master, Lion vs. Lion, Dancing Lion, The Great Lion Kun Seng Keng, The Lion Men, The Lion Men: Ultimate Showdown, Lion Dancing and Lion Dancing 2 and I Am What I Am. Northern Lion Dancing appeared in Disney's 1998 film Mulan, when the Hun villains use it to sneak into the imperial city under the disguise of a large imperial Lion.

Lion dance has also appeared in popular music videos, such as Chinese hip hop group Higher Brothers music video for their single "Open It Up", Adam Lambert's music video "If I Had You", and Zayn Malik featuring Sia's music video "Dusk Till Dawn". The same traditional dance also appeared in a music video "True To Your Heart" by 98 Degrees featuring Stevie Wonder, which was used to advertise the 1998 Disney animated film Mulan.

Version 4.4 of the video game Genshin Impact introduced the playable character Gaming, a "Wushou Dance" performer, which is Liyue's version of the lion dance. Another video game, Wuthering Waves features the character Lingyang, a "Liondancer" from the city of Jinzhou. The Elden Ring Shadow of the Erdtree downloadable content introduces a new boss named Divine Beast Dancing Lion. Its appearance is more akin to that of the Chinese Northern Lion.

See also

- Chinese New Year

- Japanese New Year

- Vietnamese New Year (Tết)

- Korean New Year

- Culture of China

- Chinese guardian lions

- Dance in China

- Pantomime horse

- Dragon dance

- Tiger dance

- Qilin dance

- Shisa

References

- ^ Fan Pen Li Che (2007). Chinese Shadow Theatre: History, Popular Religion, and Women Warriors. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0773531970.

- "Shang Shu - Yu Shu - Yi and Ji". Chinese Text Project.

- Wang Kefen (1985). The History of Chinese Dance. China Books & Periodicals. pp. 25–27. ISBN 978-0835111867.

- Faye Chunfang Fei, ed. (2002). Chinese Theories of Theater and Performance from Confucius to the Present. University of Michigan Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0472089239.

- ^ "Hinc sunt leones — two ancient Eurasian migratory terms in Chinese revisited" (PDF). International Journal of Central Asian Studies. 9. 2004. ISSN 1226-4490. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2015-02-21.

- Berthold Laufer (1976). Kleinere Schriften: Publikationen aus der Zeit von 1911 bis 1925. 2 v. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 1444. ISBN 978-3515026512.

- Mona Schrempf (2002), "chapter 6 - The Earth-Ox and Snowlion", in Toni Huber (ed.), Amdo Tibetans in Transition: Society and Culture in the Post-Mao Era, Brill, p. 164, ISBN 9004125965,

During the Persian New Year of Newruz, a lion dance used to be performed by young boys, some of them naked it seems, who were sprinkled with cold water. They were thus supposed to drive out evil forces and the cold of the winter.

- ^ Marianne Hulsbosch; Elizabeth Bedford; Martha Chaiklin, eds. (2010). Asian Material Culture. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 112–118. ISBN 9789089640901.

- ^ Laurence E. R. Picken (1984). Music for a Lion Dance of the Song Dynasty. Musica Asiatica: volume 4. Cambridge University Press. p. 201. ISBN 978-0521278379.

- Wolfgang Behr (2004). "Hinc sunt leones — two ancient Eurasian migratory terms in Chinese revisited" (PDF). International Journal of Central Asian Studies. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2015-02-21.

- Wilt L. Idema, ed. (1985). The Dramatic Oeuvre of Chu Yu-Tun: 1379 - 1439. Brill. p. 52. ISBN 9789004072916.

- ^ Wang Kefen (1985). The History of Chinese Dance. China Books & Periodicals. p. 53. ISBN 978-0835111867.

- 漢書 卷二十二 ‧ 禮樂志第二,

Original text: 孟康曰:「象人,若今戲蝦魚師子者也。」translation: Xiàngrén (Imitators) are like those who act as frogs, fish, or lions today

- "伎乐盛境". 佛教文化. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2014-01-10.

- "洛陽伽藍記/卷一".

四月四日,此像常出,辟邪師子導引其前。吞刀吐火,騰驤一面;彩幢上索,詭譎不常。奇伎異服,冠於都市。

- Seiroku Noma (1943). Nihon kamen shi 日本假面史. Geibun Shoin.

- "通典/卷146". Tongdian. Original text: 太平樂,亦謂之五方師子舞。師子摯獸,出於西南夷天竺、師子等國。綴毛為衣,象其俛仰馴狎之容。二人持繩拂,為習弄之狀。五師子各依其方色,百四十人歌太平樂,舞抃以從之,服飾皆作崑崙象。

- Carol Stepanchuk; Charles Choy Wong (1992). Mooncakes and Hungry Ghosts: Festivals of China. China Books & Periodicals. p. 38. ISBN 978-0835124812.

- "樂府雜錄". Yuefu Zalu.

Original text: 戲有五方獅子,高丈餘,各衣五色。每一獅子有十二人,戴紅抹額,衣畫衣,執紅拂子,謂之「獅子郎」,舞《太平樂》曲。

- "《西凉伎》". Archived from the original on 2014-02-19. Retrieved 2014-01-12.

西凉伎,假面胡人假狮子。刻木为头丝作尾,金镀眼睛银贴齿。奋迅毛衣摆双耳,如从流沙来万里。紫髯深目两胡儿,鼓舞跳粱前致辞。

- 陳正平 (2000). 唐詩趣談. Taiwan study published Ltd. pp. 140–145. ISBN 978-9866318580.

- Dorothy Perkins, ed. (1998). Encyclopedia of China: History and Culture. Facts On File Inc. p. 354. ISBN 978-0816026937.

- ^ "Lion Dance". China Daily.

- "South Lion: the Guangzhou Lion Dance". Life of Guangzhou. 13 February 2009. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- "Taipei (Taiwanese Lion)". Shaolin Lohan Pai Dance Troupe. Archived from the original on 2014-08-10.

- "狮舞(青狮)项目简介". Archived from the original on 2017-07-19. Retrieved 2014-01-28.

- Chan, Margaret (2006). Ritual is Theatre, Theatre is Ritual. Wee Kim Wee Centre, Singapore Management University. p. 159. ISBN 9789812481153.

- "沈丘回族文狮舞". The People's Government of Henan Province.

- "沈丘槐店文狮舞1". 回族文狮子文化网. Archived from the original on 2014-02-04.

- "Folk artists rehearse lion dance for upcoming Chinese Lunar New Year in China's Gansu". Xinhua. 22 December 2019. Archived from the original on December 22, 2019.

- 陳正平 (2000). 唐詩趣談. Taiwan study published Ltd. p. 146. ISBN 978-9866318580.

- "Besides The Lion". The Lion Arts. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017.

- "Qilin Dancing During the Lunar New Year and Southern Chinese Martial Culture". Kung Fu Tea. 10 February 2013.

- "The Hakka Chinese: Their Origin, Folk Songs And Nursery Rhymes". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-02-03.

- ^ "The Difference in Lion Dance". The Lion Arts. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-01-11.

- Feltham, Heleanor B. (2009). Elizabeth Bedford; Marianne Hulsbosch; Martha Chaiklin (eds.). Asian Material Culture. Amsterdam University Press. p. 112. ISBN 9789089640901.

- Benji Chang (2013). "Chinese Lion Dance in the United States". In Xiaojian Zhao; Edward J.W. Park (eds.). Asian Americans: An Encyclopedia of Social, Cultural, Economic, and Political History. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-1598842395.

- "Making a Chinese Lion Head". The Chinese Art of Lion Dancing. Archived from the original on 2014-02-22.

- Lim Chey Cheng. "The Lion Dance Costume Maker" (PDF). Friends of the Museums.

- Chow Ee-Tan (February 12, 1996). "Lion Dance King". New Straits Times.

- "About Us". Singapore Hok San Association.

- "Southern (Cantonese) Lions". Shaolin Lohan Pai Lion Dance Troupe. Archived from the original on 2014-02-01.

- "醒獅的由來". Archived from the original on 2008-06-27.

- ^ "Hidden Meanings In the Southern Cantonese Lion Dance Costume". Chinese Lion Dancers. Archived from the original on 28 August 2011.

- ^ "Green Lion 青狮". Chinatownology.

- ^ "The people of Wufu are prosperous and the auspicious beasts are coming─ Talking about the Hakka Kirin Dance". Archived from the original on 2017-03-25.

- ^ Lo, Wai Ling (1 June 2022). "Recreating Local Tradition: The Study of the Hang Hau Hakka Unicorn Dance in Hong Kong". Asian Studies, the Twelfth International Convention of Asia Scholars (ICAS 12). 1: 401–406. doi:10.5117/9789048557820/icas.2022.047. ISBN 9789048557820. ISSN 2949-6721.

- ^ "What Is The Qilin Dance?". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 2023-10-10.

- "What Is The Qilin Dance?". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 2023-10-10.

- "Lion Dance in Tay and Nung Ethnic Culture". Haivenu Travel Blogs. Archived from the original on 2016-06-24. Retrieved 2016-05-21.

- "Nha Nhac of Hue Court". Vietnamese Dance. April 15, 2011.

- "Ông Địa". Phật Giáo Hòa Háo Texas. Archived from the original on March 4, 2007.

- ^ Herbert Plutschow (November 5, 2013). Matsuri: The Festivals of Japan: With a Selection from P.G. O'Neill's Photographic Archive of Matsuri. Routledge. pp. 131–132. ISBN 9781134246984.

- Marianne Hulsbosch; Elizabeth Bedford; Martha Chaiklin, eds. (2010). Asian Material Culture. Amsterdam University Press. p. 110. ISBN 9789089640901.

- "Let a Lion Bite Your Head (for Good Luck)". Deep Japan. 15 March 2014.

- "Kobe, 1906 New Year Celebrations 13". Old Photos of Japan. 31 December 2008.

- ^ Benito Ortolani (1995). The Japanese Theatre: From Shamanistic Ritual to Contemporary Pluralism. Princeton University Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0691043333.

- Benito Ortolani (1995). The Japanese Theatre: From Shamanistic Ritual to Contemporary Pluralism. Princeton University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0691043333.

- Terence Lancashire (2011). An Introduction to Japanese Folk Performing Arts. Ashgate. p. 7. ISBN 978-1409431336.

- ^ Yonei Teruyoshi. "Shishi-mai". Encyclopedia of Shinto.

- "石橋物".

- Brian Bocking (1997). A Popular Dictionary of Shinto. Routledge. p. 134. ISBN 978-0700710515.

- "Sounds of Korea > Lion Dance". KBS World Radio. April 7, 2013. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- ^ Keith Pratt; Richard Rutt, eds. (1999). Korea: A Historical and Cultural Dictionary. Routledge. p. 271. ISBN 978-0700704637.

- "Eunyul Talchum (Mask Dance Drama of Eunyul)". Cultural Heritage Administration.

- "Korean Mask Dances". Asianinfo.org.

- ^ National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage (25 December 2015). Tal and Talchum. Gil-Job-Ie Media. p. 27. ISBN 9788963257358.

- "Traditions revived during Seollal holidays". Korean Herald. 2010-04-04.

- "Masks & the Mask Dance". Korea.net. September 16, 2014.

- "Bukcheong Saja-nori". Asia-Pacific Database on Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH).

- "Tibetan Snow Lion Dance". Tibet Views. Archived from the original on 2018-11-28. Retrieved 2014-01-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Tawang Festival". India Travel. Archived from the original on 2013-01-25.

- Shobhna Gupta (2007). Dances of India. Har-Anand. p. 76. ISBN 978-8124108666.

- ^ Mona Schrempf (2002), Toni Huber (ed.), Amdo Tibetans in Transition: Society and Culture in the Post-Mao Era (PDF), Brill, pp. 147–169, ISBN 9004125965

- "Cham dances". Material Tibet.

- "Gar Cham – Meditative Dance – "Lama Dance"". Samye.

- "Legend of the SnowLion". Snow Lion Tour. 21 March 2013.

- "Tibetan Buddhist Symbols". A view on Buddhism.

- "Chhau Mask". INDIAN CULTURE. Ministry of Culture (India). Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- "600 school students to perform dance on Republic Day | India.com". www.india.com. Zee Media Corporation. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- "Artists from various States depict culture". The Hitavada. Progressive Writers and Publishers. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- Gajrani, Shiv (2004). History, Religion and Culture of India. Delhi: Gyan Publishing House. pp. 101–103. ISBN 978-81-8205-061-7. Retrieved 19 August 2023.

- "Sisingaan, Sindiran Ala Orang Sunda". Indonesia.go.id (in Indonesian). 23 December 2019.

- Dipa, Arya (3 June 2014). "Preserving hamlets via art in Sekejolang". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 2021-02-25.

- "Sisingaan". kompas.id. Retrieved 2021-02-25.

- Istvan Praet (15 August 2013). Animism and the Question of Life. Routledge. p. 83. ISBN 9781134500598.

- Paul Spencer (March 2004). The Maasai of Matapato: A Study of Rituals of Rebellion. Routledge. p. 147. ISBN 9781134371662.

- "Warriors of the Maasai".

- N. W. Sobania (2000). Culture and Customs of Kenya. Praeger Publishers. p. 205. ISBN 978-0313314865.

- "Why Lion Dancers Throw Lettuce Everywhere – A Guide to Choy Cheng". Vancouver Lion Dance by Chau Luen Athletics.

- Marianne Hulsbosch; Elizabeth Bedford; Martha Chaiklin, eds. (2010). Asian Material Culture. Amsterdam University Press. p. 117. ISBN 9789089640901.

- Yap, Joey. The Art of Lion Dance. pp. 102, 105. ISBN 9789671303870.

- Malaysia Muar Lion Dance Troupe is World Champion|New Straits Times |11 February 1994

- Wang, Marina (9 February 2021). "Malaysia Has Turned Lion Dancing Into a Gravity-Defying Extreme Sport". Atlas Obscura.

- Elan Perumal (28 July 2018). "Lion dancers dazzle with football stunts". The Star.

- "Who will be The Lion (dance) King?". Straits Times. 10 September 2019.

- ^ Sharon A. Carstens (2012). "Chapter 8, Dancing Lions and Disappearing History: The National Culture Debates and Chinese Malaysian Culture". Histories, Cultures, Identities: Studies in Malaysian Chinese Worlds. NUS Press. pp. 144–169. ISBN 978-9971693121.

- Wanning Sun, ed. (2006). Media and the Chinese Diaspora: Community, Communications and Commerce. Routledge. p. 10. ISBN 978-0415352048.

- by M. Jocelyn Armstrong; R. Warwick Armstrong; K. Mulliner, eds. (2001). Chinese Populations in Contemporary Southeast Asian Societies: Identities, Interdependence and International Influence. Routledge. p. 222. ISBN 978-0700713981.

- Jean Elizabeth DeBernardi (2004). Penang: Rites of Belonging in a Malaysian Chinese Community. Stanford University Press. p. 255. ISBN 978-0804744867.

- Leo Suryadinata (2008). Ethnic Chinese in Contemporary Indonesia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

- "Chinese Lion Dance Banned in Indonesia's Aceh". Jakarta Globe. December 21, 2009. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- "Pacific Overtures". The Stephen Sondheim Reference Guide.

- ^ Sheppard, William Anthony (2019). Extreme Exoticism. p. 373. ISBN 9780190072704.

- "How to beat the Divine Beast Dancing Lion in Shadow of the Erdtree". 4 June 2024.

External links

- The Genuine History Of Lion Dance Archived 2016-03-23 at the Wayback Machine

- The Beginner’s Guide to Chinese Lion Dance

- An in-depth article on the Chinese Lion Dance

- Information about Green Lions

- Additional information about lion dance

- The Chinese Lion Dance

- Malaysia Muar Lion Dance Troupe is World Champion, New Straits Times 11 February 1994

- Korean Insights – Madangguk: Mask Dance-Drama

| Chinese New Year | |

|---|---|

| Culture of China | |

| Topics | |

| Food | |

| Other | |

| Related | |

| Golden Week | |