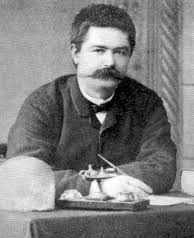

| Beşir Fuad | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 1852 Constantinople, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 5 February 1887(1887-02-05) (aged 34–35) Constantinople, Ottoman Empire |

| Nationality | Ottoman |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1883–1887 |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1873–1884 |

| Rank | Binbashi |

| Wars | |

Beşir Fuad (c. 1852 – 5 February 1887) was an Ottoman soldier, intellectual, and writer during the First Constitutional Era.

He wrote works on science, philosophy, literary criticism and biography. Unlike Tanzimat era intellectuals, who generally subscribed to romanticism, he promulgated realism and naturalism in literature; and positivism in philosophy. He has been called "the first Turkish positivist and naturalist".

His suicide at the age of 35 had wide repercussions in the Ottoman society and the press, which were unfamiliar with the concept of suicide until then. His death is reported with starting a suicide epidemic in Istanbul.

Early life and military career

Beşir Fuad was born in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) to a family of Georgian descent. He was the son of Habibe Hanım and Hurşid Pasha, who had served as mutasarrif of Marash and Adana.

After graduating from Fatih Highschool, he continued his education at the Aleppo Jesuit School in Syria, where his father was posted. During his stay in Aleppo, he learned French. He graduated from Kuleli Military High School in 1871 and the Ottoman Military Academy in 1873. After graduating, he served as an aide-de-camp to Sultan Abdulaziz for three years. When the Serbian-Ottoman war of 1876-1877 began, he joined the army as a volunteer. Afterwards, he took part in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 and the suppression of the Cretan revolt of 1878; achieving the rank of bimbashi (lieutenant colonel). He stayed in Crete for several years, and learned English and German during this time.

His marriage to an aunt was arranged when he was very young, he had a son named Mehmet Cemil from this marriage. He divorced a short time later and married Şaziye Hanım, daughter of Salih Pasha, a son of the palace doctor Kadri Pasha. He had two sons from this marriage, Namık Kemal and Mehmed Selim. He also had a daughter named Feride, born to a French mistress.

Career as a writer

Beşir Fuad was interested in science and philosophy, and thanks to his knowledge of English, French and German, he was able to keep up with Western intellectual and artistic developments. He started his career as a writer in 1883 by translating articles for the Envâr-ı Zekâ magazine. He left the military in 1884, and from then he devoted himself entirely to writing.

He published over 200 articles on science, philosophy, language learning and the military; as well as reviews of theatrical plays. During his short writing career, he also published 16 books, and introduced Western figures such as Émile Zola, Alphonse Daudet, Charles Dickens, Gustave Flaubert, Auguste Comte, Karl Georg Büchner, Herbert Spencer, Jean le Rond d'Alembert, Julien Offray de La Mettrie, Diderot Claude Bernard and Gabriel Tarde to the Ottoman audience.

He published the magazine Hâver, later Güneş, which ran for 12 issues. He wrote the editorials of Ceride-i Havadis for a month and a half. After the closure of that newspaper, he wrote articles for Tercüman-ı Adalet and Saadet.

Despite not writing any literature himself, he engaged in literary criticism, often contradicting the dominant views in the Ottoman Empire at the time. He defended the power and value of science and philosophy against the Romantic writers of the period, engaging in fierce arguments with Mehmet Tahir and Namık Kemal. He expressed his thoughts on art and philosophy in his work Intikad, which includes his correspondence with Muallim Naci. Upon the death of Victor Hugo in 1885, he wrote a small book about him. This work is considered the first critical monograph written in the history of Turkish literature. In another monograph on Voltaire, he defended positivism.

Death

His son Namık Kemal died at the age of one and a half years old from scarlet fever in 1885, and Beşir Fuad could not get over the impact of the loss. After his mother (who suffered a mental illness) died in March 1886, he started worrying because he thought the disease could be hereditary. He turned to nightlife and had several mistresses, being torn between them and his wife. He had a daughter, Feride, from a French mistress. He fell into financial difficulties by spending his father's inheritance, and decided to kill himself. He took the decision two years before he carried it out, also motivated by his disbelief in afterlife.

He committed suicide on February 5, 1887 by cutting his wrists in his house. He first injected himself with cocaine to relieve the pain, and then cut his wrists. He took notes while he remained conscious, regarding his suicide as a scientific experiment:

I performed my operation and did not feel any pain. It hurts a little as the blood flows out. My sister-in-law came downstairs while the blood was flowing. I told her I shut the door because I was writing and send her back. Fortunately she did not come in. I cannot think of a sweeter death than this. I raised my arm like fury to let the blood out. I started to feel dizzy...

He had intended to donate his body to the Imperial School of Medicine, but he was buried in Eyüp Cemetery instead. His tomb was later lost. Beşir Fuad's death was widely reported in the press. Since suicide was a rarely discussed topic in the Ottoman Empire, it was reported as starting a suicide epidemic in Istanbul. Subsequently, Abdul Hamid II's government banned newspapers from publishing news involving suicide.

References

- ^ "Beşir Fuad". Biografya. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ Arslan, Devrim Ulaş; Işıklar Koçak, Müge (2014). "Beşir Fuad as a Self-Appointed Agent of Change: A Microhistorical Study". I.U. Journal of Translation Studies (8): 40–64. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ Şener, Recep. "Beşir Fuad ve İntihar Salgınımız". Futuristika (in Turkish). Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ Bardakçı, Murat (11 January 1998). "İstanbul'da intihar salgını". Hürriyet (in Turkish). Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- Çalışkan, Kerem (12 November 2018). "Beşir Fuad ya da bileklerini kesip kanıyla intihar mektubu yazan kardeşimiz". Vatan Kitap (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "Özkıyım". Futuristika (in Turkish). 8 January 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- Doğu, Pınar (11 February 2013). "Beşir Fuad: Yanlış Kardeşim Benim..." T24 (in Turkish). Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ Zarcone, Thierry. "Beşir Fuad". Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_24332. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- 1850s births

- 1887 deaths

- 1880s suicides

- 19th-century journalists from the Ottoman Empire

- Opinion journalists

- 19th-century translators

- Positivists

- Materialists

- Journalists from Istanbul

- Political people from the Ottoman Empire

- Philosophers from the Ottoman Empire

- Georgians from the Ottoman Empire

- Suicides in the Ottoman Empire

- Suicides by sharp instrument in Turkey

- Kuleli Military High School alumni

- Ottoman Military Academy alumni

- Ottoman Army officers

- Serbian–Turkish Wars (1876–1878)

- Ottoman military personnel of the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878)

- Burials at Eyüp Cemetery

- Military personnel who died by suicide