| Part of a series on |

| Numismatics the study of currency |

|---|

|

| Currency |

| History of money |

| Production |

| Collection |

A cheque (or check in American English; see spelling differences) is a document that orders a bank, building society (or credit union) to pay a specific amount of money from a person's account to the person in whose name the cheque has been issued. The person writing the cheque, known as the drawer, has a transaction banking account (often called a current, cheque, chequing, checking, or share draft account) where the money is held. The drawer writes various details including the monetary amount, date, and a payee on the cheque, and signs it, ordering their bank, known as the drawee, to pay the amount of money stated to the payee.

Although forms of cheques have been in use since ancient times and at least since the 9th century, they became a highly popular non-cash method for making payments during the 20th century and usage of cheques peaked. By the second half of the 20th century, as cheque processing became automated, billions of cheques were issued annually; these volumes peaked in or around the early 1990s. Since then cheque usage has fallen, being replaced by electronic payment systems, such as debit cards and credit cards. In an increasing number of countries cheques have either become a marginal payment system or have been completely phased out.

Nature of a cheque

A cheque is a negotiable instrument instructing a financial institution to pay a specific amount of a specific currency from a specified transactional account held in the drawer's name with that institution. Both the drawer and payee may be natural persons or legal entities. Cheques are order instruments, and are not in general payable simply to the bearer as bearer instruments are, but must be paid to the payee. In some countries, such as the US, the payee may endorse the cheque, allowing them to specify a third party to whom it should be paid.

Cheques are a type of bill of exchange that were developed as a way to make payments without the need to carry large amounts of money. Paper money evolved from promissory notes, another form of negotiable instrument similar to cheques in that they were originally a written order to pay the given amount to whoever had it in their possession (the "bearer").

Spelling and etymology

Check is the original spelling in the English language. The newer spelling, cheque (from the French), is believed to have come into use around 1828, when the switch was made by James William Gilbart in his Practical Treatise on Banking. The spellings check, checque, and cheque were used interchangeably from the 17th century until the 20th century. However, since the 19th century, in the Commonwealth and Ireland, the spelling cheque (from the French word chèque) has become standard for the financial instrument, while check is used only for other meanings, thus distinguishing the two definitions in writing.

In American English, the usual spelling for both is check.

Etymological dictionaries attribute the financial meaning of check to come from "a check against forgery", with the use of "check" to mean "control" stemming from the check used in chess, a term which came into English through French, Latin, Arabic, and ultimately from the Persian word shah, or "king".

History

For broader coverage of this topic, see History of banking.The cheque had its origins in the ancient banking system, in which bankers would issue orders at the request of their customers, to pay money to identified payees. Such an order was referred to as a bill of exchange. The use of bills of exchange facilitated trade by eliminating the need for merchants to carry large quantities of currency (for example, gold) to purchase goods and services.

Early years

There is early evidence of using bill of exchange. In India, during the Maurya Empire (from 321 to 185 BC), a commercial instrument called the adesha was in use, which was an order on a banker desiring him to pay the money of the note to a third person.

The ancient Romans are believed to have used an early form of cheque known as praescriptiones in the 1st century BC.

Beginning in the third century AD, banks in Persian territory began to issue letters of credit. These letters were termed čak, meaning "document" or "contract". The čak became the sakk later used by traders in the Abbasid Caliphate and other Arab-ruled lands. Transporting a paper sakk was more secure than transporting money. In the ninth century, a merchant in one country could cash a sakk drawn on his bank in another country. The Persian poet, Ferdowsi, used the term "cheque" several times in his famous book, Shahnameh, when referring to the Sasanid dynasty.

Ibn Hawqal, living in the 10th century, records the use of a cheque written in Aoudaghost which was worth 42,000 dinars.

In the 13th century the bill of exchange was developed in Venice as a legal device to allow international trade without the need to carry large amounts of gold and silver. Their use subsequently spread to other European countries.

In the early 1500s, to protect large accumulations of cash, people in the Dutch Republic began depositing their money with "cashiers". These cashiers held the money for a fee. Competition drove cashiers to offer additional services including paying money to any person bearing a written order from a depositor to do so. They kept the note as proof of payment. This concept went on to spread to England and elsewhere.

Modern era

By the 17th century, bills of exchange were being used for domestic payments in England. Cheques, a type of bill of exchange, then began to evolve. Initially, they were called drawn notes, because they enabled a customer to draw on the funds that he or she had in the account with a bank and required immediate payment. These were handwritten, and one of the earliest known still to be in existence was drawn on Messrs Morris and Clayton, scriveners and bankers based in the City of London, and dated 16 February 1659.

In 1717, the Bank of England pioneered the first use of a pre-printed form. These forms were printed on "cheque paper" to prevent fraud, and customers had to attend in person and obtain a numbered form from the cashier. Once written, the cheque was brought back to the bank for settlement. The suppression of banknotes in eighteenth-century England further promoted the use of cheques.

Until about 1770, an informal exchange of cheques took place between London banks. Clerks of each bank visited all the other banks to exchange cheques while keeping a tally of balances between them until they settled with each other. Daily cheque clearing began around 1770 when the bank clerks met at the Five Bells, a tavern in Lombard Street in the City of London, to exchange all their cheques in one place and settle the balances in cash. This was the first bankers' clearing house.

Provincial clearinghouses were established in major cities throughout the UK to facilitate the clearing of cheques on banks in the same town. Birmingham, Bradford, Bristol, Hull, Leeds, Leicester, Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle, Nottingham, Sheffield, and Southampton all had their own clearinghouses.

In America, the Bank of New York began issuing cheques after its establishment by Alexander Hamilton in 1784. The oldest surviving example of a complete American chequebook from the 1790s was discovered by a family in New Jersey. The documents are in some ways similar to modern-day cheques, with some data pre-printed on sheets of paper alongside blank spaces for where other information could be hand-written as needed.

It is thought that the Commercial Bank of Scotland was the first bank to personalize its customers' cheques, in 1811, by printing the name of the account holder vertically along the left-hand edge. In 1830 the Bank of England introduced books of 50, 100, and 200 forms and counterparts, bound or stitched. These cheque books became a common format for the distribution of cheques to bank customers.

In the late 19th century, several countries formalized laws regarding cheques. The UK passed the Bills of Exchange Act 1882, and India passed the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881; which both covered cheques.

In 1931, an attempt was made to simplify the international use of cheques by the Geneva Convention on the Unification of the Law Relating to Cheques. Many European and South American states, as well as Japan, joined the convention. However, countries including the US and members of the British Commonwealth did not participate and so it remained very difficult for cheques to be used across country borders.

In 1959 a standard for machine-readable characters (MICR) was agreed upon and patented in the US for use with cheques. This opened the way for the first automated reader/sorting machines for clearing cheques. As automation increased, the following years saw a dramatic change in the way in which cheques were handled and processed. Cheque volumes continued to grow; in the late 20th century, cheques were the most popular non-cash method for making payments, with billions of them processed each year. Most countries saw cheque volumes peak in the late 1980s or early 1990s, after which electronic payment methods became more popular and the use of cheques declined.

In 1969 cheque guarantee cards were introduced in several countries, allowing a retailer to confirm that a cheque would be honored when used at a point of sale. The drawer would sign the cheque in front of the retailer, who would compare the signature to the signature on the card and then write the cheque-guarantee-card number on the back of the cheque. Such cards were generally phased out and replaced by debit cards, starting in the mid-1990s.

From the mid-1990s, many countries enacted laws to allow for cheque truncation, in which a physical cheque is converted into electronic form for transmission to the paying bank or clearing-house. This eliminates the cumbersome physical presentation and saves time and processing costs.

In 2002, the Eurocheque system was phased out and replaced with domestic clearing systems. Old Eurocheques could still be used, but they were now processed by national clearing systems. At that time, several countries took the opportunity to phase out the use of cheques altogether. As of 2010, many countries have either phased out the use of cheques altogether or signaled that they would do so in the future.

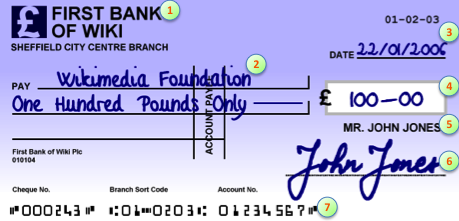

Parts of a cheque

- Drawee

- Payee

- Date of issue

- Amount of currency

- Drawer

- Signature of drawer

- Machine-readable routing and account information

The four main items on a cheque are:

- Drawer: the person or entity whose transaction account is to be drawn. Usually, the drawer's name and account is preprinted on the cheque, and the drawer is usually the signatory.

- Payee: the person or entity who is to be paid the amount.

- Drawee: the bank or other financial institution where the cheque can be presented for payment. This is usually preprinted on the cheque.

- Amount: the currency amount. The amount and currency (e.g., dollars, pounds, etc.) usually must be written in words and in figures. The currency is usually the local currency, but may be a foreign currency.

As cheque usage increased during the 19th and 20th centuries, additional items were added to increase security or to make processing easier for the financial institution. A signature of the drawer was required to authorize the cheque, and this is the main way to authenticate the cheque. Second, it became customary to write the amount in words as well as in numbers to avoid mistakes and make it harder to fraudulently alter the amount after the cheque had been written. It is not a legal requirement to write the amount in words, although some banks will refuse to accept cheques that do not have the amount in both numbers and words.

An issue date was added, and cheques may become invalid a certain amount of time after issue. In the US and Canada, a cheque is typically valid for six months after the date of issue, after which it is a stale-dated cheque, but this depends on where the cheque is drawn. In Australia, a cheque is typically valid for fifteen months of the cheque date. A cheque that has an issue date in the future, a post-dated cheque, may not be able to be presented until that date has passed. In some countries writing a post dated cheque may simply be ignored or is illegal. Conversely, an antedated cheque has an issue date in the past.

A cheque number was added and cheque books were issued so that cheque numbers were sequential. This allowed for some basic fraud detection by banks and made sure one cheque was not presented twice.

In some countries, such as the US, cheques may contain a memo line where the purpose of the cheque can be indicated as a convenience without affecting the official parts of the cheque. In the United Kingdom a memo line is not available and such notes may be written on the reverse side of the cheque.

In the US, at the top (when cheque oriented vertically) of the reverse side of the cheque, there are usually one or more blank lines labelled something like "Endorse here".

Starting in the 1960s, machine-readable routing and account information was added to the bottom of cheques in MICR format, which allowed automated sorting and routing of cheques between banks and led to automated central clearing facilities. The information provided at the bottom of the cheque is country-specific and standards are set by each country's cheque clearing system. This means that the payee no longer has to go to the bank that issued the cheque, they can instead deposit it at their own bank or any other bank and the cheque would be routed back to the originating bank, and funds transferred to their own bank account.

In the US, the bottom 5⁄8-inch (16 mm) of the cheque is reserved for MICR characters only. Intrusion into the MICR area can cause problems when the cheque runs through the clearinghouse, requiring someone to print an MICR cheque correction strip and glue it to the cheque. Many new ATMs do not use deposit envelopes and actually scan the cheque at the time it is deposited and will reject cheques due to handwriting incursion which interferes with reading the MICR. This can cause considerable inconvenience as the depositor may have to wait days for the bank to be open and may have difficulty getting to the bank even when they are open; this can delay the availability of the portion of a deposit which their bank makes available immediately as well as the balance of the deposit. Terms of service for many mobile (cell phone camera) deposits also require the MICR section to be readable. Not all of the MICR characters have been printed at the time the cheque is written, as additional characters will be printed later to encode the amount; thus a sloppy signature could obscure characters that will later be printed there. Since MICR characters are no longer necessarily printed in magnetic ink and will be scanned by optical rather than magnetic means, the readers will be unable to distinguish pen ink from pre-printed magnetic ink; these changes allow cheques to be printed on ordinary home and office printers without requiring pre-printed cheque forms, allow ATM deposit capture, allow mobile deposits, and facilitate electronic copies of cheques.

For additional protection, a cheque can be crossed, which restricts the use of the cheque so that the funds must be paid into a bank account. The format and wording varies from country to country, but generally two parallel lines may be placed either vertically across the cheque or in the top left hand corner. In addition the words 'or bearer' must not be used, or if pre-printed on the cheque must be crossed out on the payee line. If the cheque is crossed with the words 'Account Payee' or similar then the cheque can only be paid into the bank account of the person initially named as the payee, thus it cannot be endorsed to a different payee.

Attached documents

Cheques sometimes include additional documents. A page in a chequebook may consist of both the cheque itself and a stub or counterfoil – when the cheque is written, only the cheque itself is detached, and the stub is retained in the chequebook as a record of the cheque. Alternatively, cheques may be recorded with carbon paper behind each cheque, in ledger sheets between cheques or at the back of a chequebook, or in a completely separate transaction register that comes with a chequebook.

When a cheque is mailed, a separate letter or "remittance advice" may be attached to inform the recipient of the purpose of the cheque – formally, which account receivable to credit the funds to. This is frequently done formally using a provided slip when paying a bill, or informally via a letter when sending an ad hoc cheque.

Usage

See also: § Cheques around the world

Parties to regular cheques generally include a drawer, the depositor writing a cheque; a drawee, the financial institution where the cheque can be presented for payment; and a payee, the entity to whom the drawer issues the cheque. The drawer drafts or draws a cheque, which is also called cutting a cheque, especially in the US. There may also be a beneficiary—for example, in depositing a cheque with a custodian of a brokerage account, the payee will be the custodian, but the cheque may be marked "F/B/O" ("for the benefit of") the beneficiary.

Ultimately, there is also at least one endorsee which would typically be the financial institution servicing the payee's account, or in some circumstances may be a third party to whom the payee owes or wishes to give money.

A payee that accepts a cheque will typically deposit it in an account at the payee's bank, and have the bank process the cheque. In some cases, the payee will take the cheque to a branch of the drawee bank, and cash the cheque there. If a cheque is refused at the drawee bank (or the drawee bank returns the cheque to the bank that it was deposited at) because there are insufficient funds for the cheque to clear, it is said that the cheque has been dishonoured. Once a cheque is approved and all appropriate accounts involved have been credited, the cheque is stamped with some kind of cancellation mark, such as a "paid" stamp. The cheque is now a cancelled cheque. Cancelled cheques are placed in the account holder's file. The account holder can request a copy of a cancelled cheque as proof of a payment. This is known as the cheque clearing cycle.

Cheques can be lost or go astray within the cycle, or be delayed if further verification is needed in the case of suspected fraud. A cheque may thus bounce some time after it has been deposited.

Following concerns about the amount of time it took the Cheque and Credit Clearing Company to clear cheques, the United Kingdom Office of Fair Trading set up a working group in 2006 to look at the cheque clearing cycle. Their report said that clearing times could be improved, but that the costs associated with speeding up the cheque clearing cycle could not be justified considering the use of cheques was declining. However, they concluded the biggest problem was the unlimited time a bank could take to dishonour a cheque. To address this, changes were implemented so that the maximum time after a cheque was deposited that it could be dishonoured was six days, what was known as the "certainty of fate" principle.

An advantage to the drawer of using cheques instead of debit card transactions is that they know the drawer's bank will not release the money until several days later. Paying with a cheque without adequate funds backing it and later making a deposit to the account on which the cheque is drawn in order to cover the cheque amount is called "kiting" or "floating" and is generally illegal in the US, but applicable laws are rarely enforced unless the drawer uses multiple chequing accounts with multiple institutions to increase the delay or to steal funds.

Declining use

Cheque usage has been declining since the 1990s, both for point of sale transactions (for which credit cards, debit cards or mobile payment apps are increasingly preferred) and for third party payments (for example, bill payments), where the emergence of telephone banking has accelerated the decline, online banking, and mobile banking. Being paper-based, cheques are costly for banks to process in comparison to electronic payments, so banks in many countries now discourage the use of cheques, either by charging for cheques or by making the alternatives more attractive to customers. In particular, the handling of money transfers requires more effort and is time-consuming. The cheque has to be handed over in person or sent through mail. The rise of automated teller machines (ATMs) means that small amounts of cash are often easily accessible, so that it is sometimes unnecessary to write a cheque for such amounts instead. A number of countries have announced or have already completed the end of cheques as a means of payment.

In October 2023, the average American wrote just over one check, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. The average value of these checks was $504, suggesting that most checks were used for larger purchases. This marks a significant decline from the year 2000 when Americans wrote an average of 60 checks annually.

Decline in Asia

In many Asian countries, cheques were never widely used and generally only used by the wealthy, with cash being used for the majority of payments except for India, where cheque usage was prevalent. Where cheques were used they have been declining rapidly, by 2009 there was negligible consumer cheque usage in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. This declining trend was accelerated by these developed markets advanced financial services infrastructure. Many of the developing countries in Asia have seen an increasing use of electronic payment systems, 'leap-frogging' the less efficient chequing system altogether.

Decline in Europe

In most European countries, cheques are now rarely used or have been completely phased out, even for third party payments except for the United Kingdom, France and Ireland. In most western European countries, it was standard practice for businesses to publish their bank details on invoices, to facilitate the receipt of payments by giro. Even before the introduction of online banking, it has been possible in some countries to make payments to third parties using ATMs, which may accurately and rapidly capture invoice amounts, due dates, and payee bank details via a bar code reader to reduce keying. In using a cheque, the onus is on the payee to initiate the payment, whereas with a giro transfer, the onus is on the payer to effect the payment.

In the United Kingdom, France and Ireland cheques continued to be used as cheque payments were free for the consumer. However these countries have also seen significant declines since 2000. Since 2001, businesses in the United Kingdom made more electronic payments than cheque payments. The UK Payments Council announced in 2011 that cheques would continue as long as customers needed them reversing a previous target to phase out cheques by 2018.

France, remains well ahead of its European counterparts in the use of cheque payments, as seen in 2020 where it is estimated that more than 1 billion cheque payments were made, compared to Italy, the country with the next highest number of payments, with under 100 million.

Decline in North America

The United States relied heavily on cheques, due to the convenience it affords payers, and due to the absence of a high volume system for low value electronic payments. In the US, an estimated 18.3 billion cheques were paid in 2012, with a value of $25.9 trillion. However even in the United States cheque usage has seen significant decline.

Canada's usage of cheques is less than that of the US and is declining rapidly at the urging of the Canadian Banking Association. The Government of Canada claims it is 6.5 times more expensive to mail a cheque than to make a direct deposit. The Canadian Payments Association reported that in 2012, cheque use in Canada accounted for only 40% of total financial transactions.

Decline in Oceania

Both Australia and New Zealand were heavy users of cheques during the later part of the 20th century. However, following global trends both countries have seen significant decline in the use of cheques.

In Australia, following global trends, the use of cheques continues to decline. In 1994 the value of daily cheque transactions was A$25 billion; by 2004 this had dropped to only A$5 billion, almost all of this for B2B transactions. Personal cheque use is practically non-existent thanks to the longstanding use of the EFTPOS system, BPAY, electronic transfers, and debit cards. The Australian payment systems strategic plan has said it will remove cheques by 2030.

In New Zealand, payments by cheque have declined from the mid-1990s in favour of electronic payment methods. In 1993, cheques accounted for over half of transactions through the national banking system, with an annual average of 130 cheques per capita. By 2006, cheques lagged well behind EFTPOS (debit card) transaction and electronic credits, making up only nine per cent of transactions, an annual average of 41 cheque transactionz per capita. Cheques were phased out completely in 2020 and no bank nor retailer accepts them in any form.

Alternatives to cheques

Payment systems other than cheques include:

- Cash

- Debit card payments

- Credit card payments

- Direct debit (initiated by payee)

- Direct credit (initiated by payer), ACH in US, giro in Europe, Direct Entry in Australia

- Wire transfer (local and international) via banks and credit unions or else via major private vendors such as Western Union and MoneyGram

- Electronic bill payments using Internet banking

- Online payment services, e.g. WeChat Pay, Alipay, PayPal, Venmo, Unified Payments Interface, PhonePe, and Paytm

- Money orders or postal orders

Variations on regular cheques

In addition to regular cheques, a number of variations were developed to address specific needs or address issues when using a regular cheque.

Cashier's cheques and bank drafts

Main article: Cashier's checkCashier's cheques and banker's drafts, also known as bank cheques, banker's cheques or treasurer's cheques, are cheques issued against the funds of a financial institution rather than an individual account holder. Typically, the term cashier's check is used in the US and banker's draft is used in the UK and most of the Commonwealth. The mechanism differs slightly from country to country but in general the bank issuing the cheque or draft will allocate the funds at the point the cheque is drawn. This provides a guarantee, save for a failure of the bank, that it will be honoured. Cashier's cheques are perceived to be as good as cash but they are still a cheque, a misconception sometimes exploited by scam artists. A lost or stolen cheque can still be stopped like any other cheque, so payment is not completely guaranteed.

Certified cheque

Main article: Certified chequeWhen a certified cheque is drawn, the bank operating the account verifies there are currently sufficient funds in the drawer's account to honour the cheque. Those funds are then set aside in the bank's internal account until the cheque is cashed or returned by the payee. Thus, a certified cheque cannot "bounce", and its liquidity is similar to cash, absent failure of the bank. The bank indicates this fact by making a notation on the face of the cheque (technically called an acceptance).

Payroll cheque

Main article: PaycheckA cheque used to pay wages may be referred to as a payroll cheque. Even when the use of cheques for paying wages and salaries became rare, the vocabulary "pay cheque" still remained commonly used to describe the payment of wages and salaries. Payroll cheques issued by the military to soldiers, or by some other government entities to their employees, beneficiants, and creditors, are referred to as warrants.

Warrants

Main article: Warrant of paymentWarrants look like cheques and clear through the banking system like cheques, but are not drawn against cleared funds in a deposit account. A cheque differs from a warrant in that the warrant is not necessarily payable on demand and may not be negotiable. They are often issued by government entities such as the military to pay wages or suppliers. In this case they are an instruction to the entity's treasurer department to pay the warrant holder on demand or after a specified maturity date.

Traveller's cheque

Main article: Traveller's chequeA traveller's cheque is designed to allow the person signing it to make an unconditional payment to someone else as a result of paying the issuer for that privilege. Traveller's cheques can usually be replaced if lost or stolen, and people frequently used them on holiday instead of cash as many businesses used to accept traveller's cheques as currency. The use of credit or debit cards has begun to replace the traveller's cheque as the standard for vacation money due to their convenience and additional security for the retailer. As a result, many businesses no longer accept traveller's cheques.

Money or postal order

Main articles: Money order and Postal orderA cheque sold by a post office, bank, or merchant such as a grocery store for payment in favour of a third party is referred to as a money order or postal order. These are paid for in advance when the order is drawn and are guaranteed by the institution that issues them and can only be paid to the named third party. This was a common way to send low value payments to third parties, avoiding the risks associated with sending cash by post, prior to the advent of electronic payment methods.

Oversized cheques

Oversized cheques, also commonly referred to as novelty cheques, are often used in public events such as donating money to charity, announcing government grants, or giving out prizes such as those from lotteries or Publishers Clearing House sweepstakes. The cheques are commonly 18 by 36 inches (46 cm × 91 cm) in size; however, according to the Guinness Book of World Records, the largest ever is 12 by 25 metres (39 ft × 82 ft). Until recently, regardless of the size, such cheques could still be redeemed for their cash value as long as they would have the same parts as a normal cheque, although usually the oversized cheque is kept as a souvenir and a normal cheque is provided. Any bank could levy additional charges for clearing an oversized cheque. Most banks need to have the machine-readable information on the bottom of cheques read electronically, so only very limited dimensions can be allowed due to standardised equipment.

Payment vouchers

In the US some public assistance programmes such as the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children, or Aid to Families with Dependent Children make vouchers available to their beneficiaries, which are good up to a certain monetary amount for purchase of grocery items deemed eligible under the particular programme. The voucher can be deposited like any other cheque by a participating supermarket or other approved business.

Cheques around the world

Australia

The Australian Cheques Act 1986 is the body of law governing the issuance of cheques and payment orders in Australia. Procedural and practical issues governing the clearance of cheques and payment orders are handled by Australian Payments Clearing Association (APCA).

In 1999, banks adopted a system to allow faster clearance of cheques by electronically transmitting information about cheques; this brought clearance times down from five to three days. Previously, cheques were required to be physically transported to the paying bank before processing began, and dishonoured cheques were physically returned.

In June 2023 the Australian government announced it was moving to phase out the use of cheques by 2030.

Canada

In Canada, cheques standards and processing are overseen by Payments Canada. Canadian cheques can legally be written in English, French or Inuktitut. For a period Canada also had a tele-cheque, which was a paper payment item that resembles a cheque except that it is neither created nor signed by the payer—instead it is created (and may be signed) by a third party on behalf of the payer. Under CPA Rules these were prohibited in the clearing system effective 1 January 2004.

Canada's usage of cheques is less than that of the US and has been declining rapidly at the urging of the Canadian Banking Association since 2000. The Government of Canada claims it is 6.5 times more expensive to mail a cheque than to make a direct deposit. The Canadian Payments Association reported that in 2012, cheque use in Canada accounted for only 40% of total financial transactions. The Interac system, which allows instant fund transfers via chip or magnetic strip and PIN, is widely used by merchants to the point that few brick and mortar merchants accept cheques.

The Canadian government began phasing out all government cheques from April 2016.

India

Cheques were first used in India by the Bank of Hindustan, the first joint stock bank established in 1770. In 1881, the Negotiable Instruments Act (NI Act) was enacted in India, formalising the usage and characteristics of instruments like the cheque, the bill of exchange, and promissory note. The NI Act provided a legal framework for non-cash paper payment instruments in India. In 1938, the Calcutta Clearing Banks' Association, which was the largest bankers' association at that time, adopted clearing house.

Beginning in 2010, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) along with the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) piloted the cheque truncation system (CTS). Under CTS, cheques are no longer physically transported to different clearing houses. They are processed at the bank where they are presented, where an image of the cheque using Magnetic ink character recognition (MICR) is captured and digitally transmitted.

In 2009 cheques were still widely used as a means of payment in trade, and also by individuals to pay other individuals or utility bills. One of the reasons was that banks usually provided cheques for free to their individual account holders. However, cheques are now rarely accepted at point of sale in retail stores where cash and cards are payment methods of choice. Electronic payment transfer continued to gain popularity in India and like other countries this caused a subsequent reduction in volumes of cheques issued each year. In 2009 the Reserve Bank of India reported there was a five percent decline in cheque usage compared to the previous year. In 2019, the Reserve Bank of India reported that while cheque usage continued to decline, the decrease was slow. The bank attributed the slow pace of the decline due to the fact that cheque volume had briefly increased after demonetisation in 2016 before continuing to fall, as well as the efficiency of India's cheque clearing system.

Israel

Cheques were widely used in the retail market, between persons, and for other payments. The law rules that payments in cash cannot exceed 6,000 NIS, so cheque payment is a legal term when that maximum is reached. It was possible to pay at the cash desk at the supermarket or shop by cheque or issue a check for annual school payments for a child. Utility bills and property tax can be paid by cheque at the post office. Moreover, usually tenant issues twelve post-dated cheques to the landlord after signing the rental agreement: one cheque per month of the rental term; additional cheques signed by a tenant with an open date and amount for utility providers to ensure that the tenant will leave no debts.

Ten bounced cheques during a year would result in the restriction of cheques for the account, and the bank will bounce new cheques for a year. If the account owner continues to draw cheques during the restriction period, that person's accounts in Israeli banks will be denied from issuing cheques.

Japan

In Japan, cheques are called kogitte (小切手), and are governed by kogitte law.

Bounced cheques are called Fuwatari Kogitte (不渡り小切手). If an account owner bounces two cheques in six months, the bank will suspend the account for two years. If the account belongs to a public company, their stock will also be suspended from trading on the stock exchange, which can lead to bankruptcy.

New Zealand

Instrument-specific legislation includes the Cheques Act 1960, part of the Bills of Exchange Act 1908, which codifies aspects related to the cheque payment instrument, notably the procedures for the endorsement, presentment and payment of cheques. A 1995 amendment provided for the electronic presentment of cheques and removed the previous requirement to deliver cheques physically to the paying bank, opening the way for cheque truncation and imaging.

In New Zealand, cheques once banked were processed electronically together with other retail payment instruments. Homeguard v Kiwi Packaging is often cited case law regarding the banking of cheques tendered as full settlement of disputed accounts.

In New Zealand, payments by cheque have declined since the mid-1990s in favour of electronic payment methods. In 1993, cheques accounted for over half of transactions through the national banking system, with an annual average of 130 cheques per capita. By 2006 cheques lagged well behind EFTPOS (debit card) transaction and electronic credits, making up only nine per cent of transactions, an annual average of 41 cheque transaction per capita.

In 2020 New Zealand Banks began phasing out of cheques, and they are no longer accepted as payment. All have moved to other types of payment systems.Kiwibank stopped accepting cheques as payment on 28 February 2020, followed by ANZ on 31 May 2021. Westpac and BNZ stopped accepting cheques on 25 June and 30 June 2021 respectively; ASB was the last major bank to phase out cheques on 27 August 2021.

Poland

Poland withdrew cheques from use in 2006, mainly because of lack of popularity due to the widespread adoption of credit and debit cards. Electronic payments across the European Union became fast and inexpensive—usually free for consumers.

Turkey

In Turkey, cheques were usually used for commercial transactions only, and using post-dated cheques is legally permissible.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, all cheques must conform to an industry standard detailing layout and font ("Cheque and Credit Clearing Company (C&CCC) Standard 3"), be printed on a specific weight of paper (CBS1), and contain explicitly defined security features.

Since 1995, all cheque printers must be members of the Cheque Printer Accreditation Scheme (CPAS). The scheme is managed by the Cheque and Credit Clearing Company and requires that all cheques for use in the British clearing process are produced by accredited printers who have adopted stringent security standards.

The rules concerning crossed cheques are set out in Section 1 of the Cheques Act 1992 and prevent cheques being cashed by or paid into the accounts of third parties. On a crossed cheque the words "account payee only" (or similar) are printed between two parallel vertical lines in the centre of the cheque. This makes the cheque non-transferable and is to avoid cheques being endorsed and paid into an account other than that of the named payee. Crossing cheques basically ensures that the money is paid into an account of the intended beneficiary of the cheque.

Following concerns about the amount of time it took banks to clear cheques, the United Kingdom Office of Fair Trading set up a working group in 2006 to look at the cheque clearing cycle. They produced a report recommending maximum times for the cheque clearing which were introduced in UK from November 2007. In the report the date the credit appeared on the recipient's account (usually the day of deposit) was designated "T". At "T + 2" (two business days afterwards) the value would count for calculation of credit interest or overdraft interest on the recipient's account. At "T + 4" clients would be able to withdraw funds on current accounts or at "T + 6" on savings accounts (though this will often happen earlier, at the bank's discretion). "T + 6" is the last day that a cheque can bounce without the recipient's permission—this is known as "certainty of fate". Before the introduction of this standard (also known as 2-4-6 for current accounts and 2-6-6 for savings accounts), the only way to know the "fate" of a cheque has been "Special Presentation", which would normally involve a fee, where the drawee bank contacts the payee bank to see if the payee has that money at that time. "Special Presentation" had been stated at the time of deposit.

Cheque volumes peaked in 1990 when four billion cheque payments were made. Of these, 2.5 billion were cleared through the inter-bank clearing managed by the C&CCC, the remaining 1.5 billion being in-house cheques which were either paid into the branch on which they were drawn or processed intra-bank without going through the clearings. As volumes started to fall, the challenges faced by the clearing banks were then of a different nature: how to benefit from technology improvements in a declining business environment.

Although the UK did not adopt the euro as its national currency when other European countries did in 1999, many banks began offering euro denominated accounts with chequebooks, principally to business customers. The cheques can be used to pay for certain goods and services in the UK. The same year, the C&CCC set up the euro cheque clearing system to process euro denominated cheques separately from sterling cheques in Great Britain.

The UK Payments Council from 30 June 2011 withdrew the existing Cheque Guarantee Card Scheme in the UK. This service allowed cheques to be guaranteed at point of sales up to a certain value, normally £50 or £100, when signed in front of the retailer with the additional cheque guarantee card. This was after a long period of decline in their use in favour of debit cards.

In December 2009 the Payments Council announced its intention to phase out the use of cheques completely in the UK by October 2018, so long as adequate alternatives were developed. They intended to perform annual checks on the progress of other payments systems and a final review of the decision would have been held in 2016. However, the decision was reversed in 2011 after vocal public, political, and industrial opposition, and cheques have remained in use.

Since 2001, businesses in the United Kingdom have made more electronic payments than cheque payments. Automated payments rose from 753 million in 1995 to 1.1 billion in 2001 and cheques declined in that same period of time from 1.14 to 1.1 billion payments. Most British utility companies charge lower prices to customers who pay by direct debit than for other payment methods.

The vast majority of British retailers no longer accept cheques as a means of payment. Shell announced in September 2005 that it would no longer accept cheques at their UK petrol stations, a change replicated by other major fuel retailers. Within a year, Asda, Boots, Currys and WH Smith had all phased out the acceptance of cheques.

In 2016, 432 million inter-bank cheques and credit-items worth £472 billion were processed in the United Kingdom. In 2017, 405 million cheques worth £356 billion were used for payments and acquiring cash, an average of 1.2 million cheques per day, with more than 10 million being cleared in Northern Ireland alone. The Cheque and Credit Clearing Company noted that cheques continue to be highly valued for paying tradesmen and utility bills, and play a vital role in business, clubs and societies sectors, with nine in 10 business saying that they received or made payment by cheque on a monthly basis. In 2022, 150 million cheques were used to make payments in the UK, compared to 1.6 billion payments in 2006. UK Finance estimates that only 0.2% of payments (70 million transactions) will be made by cheque in 2031.

In June 2014, following a successful trial in the UK by Barclays, the UK government gave the go-ahead for a cheque truncation system, allowing people to pay in a cheque by taking a photo of it, rather than physically depositing the paper cheque at a bank. Between 2017 and 2019, the Barclays scheme was rolled out nationwide as the Image Clearing System which has sped up the processing of cheques, reducing clearing times, and allowing customers to deposit them at ATMs and through mobile and online banking applications. Mobile banking has modernised the use of cheques; in the first 6 months of 2021, 3.8 million cheques were deposited by Lloyds Bank customers. Nevertheless, in 2020-21, the use of cheques declined by 19% year on year.

Cheques are still held to be a secure and reliable means of payment: cheque fraud in the UK in 2020 totalled just £12.3 million across 185 million transactions. In the same period, online authorised payment scams totalled £479 million across 4.1 billion online payments. As such, cheques have seen a resurgence in popularity in commercial transactions from businesses to avoid the possibility of phishing fraud.

United States

| This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: sources on usage are over 10 years old. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (July 2023) |

In the United States, cheques are referred to as checks and are governed by Article 3 of the Uniform Commercial Code, under the rubric of negotiable instruments.

- An order check—the most common form in the US—is payable only to the named payee or endorsee, as it usually contains the language "Pay to the order of (name)".

- A bearer check is payable to anyone who is in possession of the document: this would be the case if the cheque does not name a payee, or is payable to "bearer" or to "cash" or "to the order of cash", or if the cheque is payable to someone who is not a person or legal entity, for example if the payee line is marked "Happy Birthday".

- A counter check is one that a bank issues to an account holder in person. This is typically done for customers who have opened a new account or have run out of personalized cheques. It may lack the usual security features.

In the US, the terminology for a cheque historically varied with the type of financial institution on which it is drawn. In the case of a savings and loan association it was a negotiable order of withdrawal (compare Negotiable Order of Withdrawal account); if a credit union it was a share draft. "Checks" were associated with chartered commercial banks. However, common usage has increasingly conformed to more recent versions of Article 3, where check means any or all of these negotiable instruments. Certain types of cheques drawn on government agencies, especially payroll cheques, may be called warrants.

At the bottom of each cheque there is the routing/account number in MICR format. The ABA routing transit number is a nine-digit number in which the first four digits identifies the US Federal Reserve Bank's cheque-processing centre. This is followed by digits 5 through 8, identifying the specific bank served by that cheque-processing centre. Digit 9 is a verification check digit, computed using a complex algorithm of the previous eight digits.

- Typically the routing number is followed by a group of eight or nine MICR digits that indicates the particular account number at that bank. The account number is assigned independently by the various banks.

- Typically the account number is followed by a group of three or four MICR digits that indicates a particular cheque number from that account.

- Directional routing number—also known as the transit number, consists of a denominator mirroring the first four digits of the routing number, and a hyphenated numerator, also known as the ABA number, in which the first part is a city code (1–49), if the account is in one of 49 specific cities, or a state code (50–99) if it is not in one of those specific cities; the second part of the hyphenated numerator mirrors the 5th through 8th digits of the routing number with leading zeros removed.

A draft in the US Uniform Commercial Code is any bill of exchange, whether payable on demand or at a later date. If payable on demand it is a "demand draft", or if drawn on a financial institution, a cheque.

The electronic cheque or substitute cheque was formally adopted in the US in 2004 with the passing of the "Check Clearing for the 21st Century Act" (or Check 21 Act). This allowed the creation of electronic cheques and translation (truncation) of paper cheques into electronic replacements, reducing cost and processing time.

The specification for US cheques is given by ANSI committee X9 Technical Report 2.

In 2002 the US still relied heavily on cheques due to the convenience afforded to payers, and due to the absence of a high volume system for low-value electronic payments. In practice, transfers of less than about five dollars are extremely expensive, and transactions of less than 50c impossible (transaction fees swallow the payment or exceed it). The only methods generally available for individuals and small businesses to make payments electronically are electronic funds transfers (EFT) or accepting credit cards. EFT payments require a commercial chequing account (which often has higher fees and minimum balances than individual accounts) and a subscription to EFT service costing anywhere from $10 to $25 a month, plus 10¢ per transaction (making transactions of 10¢ or less impossible, and transactions under $1 very expensive.) Credit card payments cost the recipient (or the payer) 33¢ plus 3% of the transaction, making transactions of 33¢ or less impossible, and transactions of $1 or less have at least a 30% service charge. Generally, payments by cheque (as long as the payer has funds in their account) and the recipient deposits it to their bank account, regardless of amount, have a service charge to both parties of zero.

Since 2002, the decline in cheque usage seen around the world has also started in the US. The cheque, although not as common as it used to be, is still a long way from disappearing completely in the US.

In the US, an estimated 18.3 billion cheques were paid in 2012, with a value of $25.9 trillion.

About 70 billion cheques were written annually in the US by 2001, though around 17 million adult Americans have no bank accounts. Certain companies whom a person pays with a cheque will turn it into an Automated Clearing House (ACH) or electronic transaction. Banks try to save time processing cheques by sending them electronically between banks. Cheque clearing is usually done through an electronic cheque broker, such as The Clearing House, Viewpointe LLC or the Federal Reserve Banks. Copies of the cheques are stored at a bank or the broker, for periods up to 99 years, and this is why some cheque archives have grown to 20 petabytes. The access to these archives is now worldwide, as most bank programming is now done offshore. Many utilities and most credit cards will also allow customers to pay by providing bank information and having the payee draw payment from the customer's account (direct debit). Many people in the US pay their bills or transfer money via paper money orders, as these have security advantages over mailing cash and require no bank-account access.

Cheque fraud

Main article: Cheque fraudCheques have been a tempting target for criminals to steal money or goods from the drawer, payee or the banks. A number of measures have been introduced to combat fraud over the years. These range from things like writing a cheque so it is difficult to alter after it is drawn, to mechanisms like crossing a cheque so that it can only be paid into another bank's account providing some traceability. However, the inherent security weaknesses of cheques as a payment method, such as having only the signature as the main authentication method and not knowing if funds will be received until the clearing cycle is complete, have made them vulnerable to a number of different types of fraud.

Embezzlement

Taking advantage of the float period (cheque kiting) to delay the notice of non-existent funds. This often involves trying to convince a merchant or other recipient, hoping the recipient will not suspect that the cheque will not clear, giving time for the fraudster to disappear.

Forgery

Sometimes, forgery is the method of choice in defrauding a bank. One form of forgery involves the use of a victim's legitimate cheques, that have either been stolen and then cashed, or altering a cheque that has been legitimately written to the perpetrator, by adding words or digits to inflate the amount.

Identity theft

Since cheques include significant personal information (name, account number, signature and in some countries driver's license number, the address or phone number of the account holder), they can be used for identity theft. The practice was discontinued as identity theft became widespread.

Dishonoured cheques

Main article: Dishonoured chequeA dishonoured cheque is literally one where the payment has not been honoured. i.e. The payment has been refused by the payer's bank, for many of various reasons. Colloquially, it is referred to as bounced. Such a cheque cannot be redeemed for its value and is worthless; they are also known as an RDI (returned deposit item), or NSF (non-sufficient funds) cheque. Cheques are usually dishonoured because the drawer's account has been frozen or limited, or because there are insufficient funds in the drawer's account when the cheque was redeemed. A cheque drawn on an account with insufficient funds is said to have bounced and may be called a rubber cheque. Banks will typically charge customers for issuing a dishonoured cheque, and in some jurisdictions such an act is a criminal action. A drawer may also issue a stop on a cheque, instructing the financial institution not to honour a particular cheque.

In England and Wales, they are typically returned marked "Refer to Drawer"—an instruction to contact the person issuing the cheque for an explanation as to why the cheque was not honoured. This wording was brought in after a bank was successfully sued for libel after returning a cheque with the phrase "Insufficient Funds" after making an error—the court ruled that as there were sufficient funds the statement was demonstrably false and damaging to the reputation of the person issuing the cheque. Despite the use of this revised phrase, successful libel lawsuits brought against banks by individuals remained for similar errors.

In Scotland, a cheque acts as an assignment of the amount of money to the payee. As such, if a cheque is dishonoured in Scotland, what funds are present in the bank account are "attached" and frozen, until either sufficient funds are credited to the account to pay the cheque, the drawer recovers the cheque and hands it into the bank, or the drawer obtains a letter from the payee stating that they have no further interest in the cheque.

A cheque may also be dishonoured because it is stale or not cashed within a "void after date". Many cheques have an explicit notice printed on the cheque that it is void after some period of days. In the US, banks are not required by the Uniform Commercial Code to honour a stale-dated cheque, which is a cheque presented six months after it is dated.

Consumer reporting

In the United States some consumer reporting agencies such as ChexSystems, Early Warning Services, and TeleCheck have been providing cheque verification services that track how people manage their chequing accounts. Banks use the agencies to screen chequing account applicants, and those with low debit scores are denied because banks cannot afford overdrawn accounts.

In the United Kingdom, in common with other items such as Direct Debits or standing orders, dishonoured cheques can be reported on a customer's credit file, although not individually and this does not happen universally amongst banks. Dishonoured payments from current accounts can be marked in the same manner as missed payments on the customer's credit report.

Lock box

Main article: Post office boxTypically when customers pay bills with cheques (like gas or water bills), the mail will go to a "lock box" at the post office. There a bank will pick up all the mail, sort it, open it, take the cheques and remittance advice out, process it all through electronic machinery, and post the funds to the proper accounts. In modern systems, taking advantage of the Check 21 Act, as in the United States many cheques are transformed into electronic objects and the paper is destroyed.

See also

- Allonge – slip of paper attached to a cheque used to endorse it when there is not enough space.

- Blank cheque – cheque where amount has been left blank.

- Certified cheque – guaranteed by a bank.

- E-cheque – electronic fund transfer.

- Hundi – historic Indian cheque-like instrument.

- Labour cheque – political concept to distribute goods in exchange for work.

- Negotiable cow – urban legend where a cow was used as a cheque.

- Substitute cheque – the act of scanning paper cheques and turning them into electronic payments.

- Transit check – a cheque which is drawn on another bank than that at which it is presented for payment.

- Traveller's cheque – a pre-paid cheque that could be used to make payments in stores.

- Railway pay cheque – identification used to collect railway workers' pay packets.

- Warrant of payment

Notes

- James William Gilbart in 1828 explains in a footnote 'Most writers spell it check. I have adopted the above form because it is free from ambiguity and is analogous to the ex-chequer, the royal treasury. It is also used by the Bank of England "Cheque Office"'.

References

- "Cheques and Bankers' Drafts Facts and Figures". UK Payment Administration (UKPA). 2010. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ Edmunds, Susan (13 May 2020). "BNZ, ANZ, Westpac to phase out cheque use". Stuff. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ "Cheques will be phased out by 2030 as the use of mobile wallets sky-rockets". ABC News. 7 June 2023.

- Conrad, Jordan (22 July 2016). "Cheque vs. Check: What's the Difference?". Writing Explained. Archived from the original on 25 July 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ Ellinger, Peter (August 1981). "Chapter 4: Negotiable Instruments". In Ziegel, Jacob S. (ed.). International Encyclopedia of Comparative Law. Vol. IX: Commercial Transactions and Institutions. Springer. p. 26. ISBN 978-90-286-0291-5.

It would appear that the modern spelling, viz. cheque came into use at about 1828, when the switch was made by Gilbart, Practical Treatise on Banking (London 1828) 14. Holden 209 points out that Chitty, On Bills of Exchange, used the old spelling, viz. check, until ed. 10 in 1859. The adherence to "check" in the United States is a commendable manifestation of independent conservativism.

- "Cheque, check". Oxford English Dictionary. London: Oxford University Press. 2009. p. 350.

- Gilbart, James William (1828). A practical treatise on Banking, containing an account of the London and County Banks ... a view of Joint Stock Banks, and the Branch Banks of the Bank of England, etc (2nd ed.). London: E. Wilson. p. 115.

- "Definition of cheque". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- Harper, Douglas. "check (n. 1)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- "check". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House. Archived from the original on 2 April 2014. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- "Publications". Reserve Bank of India. 12 December 1998. Archived from the original on 20 January 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- Durant, Will (1944). Caesar and Christ : a history of Roman civilization and of Christianity from their beginnings to A.D. 325. The story of civilization. Vol. 3. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 749.

- Safari, Meysam (2013). "Contractual structures and payoff patterns of Sukūk securities" (PDF). International Journal of Banking and Finance. 10 (2). doi:10.32890/ijbf2013.10.2.8475. S2CID 155043129. SSRN 2386365.

During the 3rd century AD, financial firms in Persia (currently known as Iran) and other territories in the Persian Sassanid Dynasty issued letters of credit known as "chak"

- Ilya Yakubovich. (2012). Journal of the American Oriental Society, 132(1), 116. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.132.1.0116

- Glubb, John Bagot (1988). A Short History of the Arab Peoples. Dorset Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-88029-226-9. OCLC 603697876.

- "How Islamic inventors changed the world". The Independent. 11 March 2006. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- Krätli, Graziano; Lydon, Ghislaine (2011). The Trans-Saharan Book Trade: Manuscript Culture, Arabic Literacy and Intellectual History in Muslim Africa. Brill Publishers. ISBN 9789004187429.

- Levtzion, Nehemia (1968). "Ibn-Hawqal, the Cheque, and Awdaghost". The Journal of African History. 9 (2): 223–333. doi:10.1017/S0021853700008847. JSTOR 179561. S2CID 162076182.

- "Guide to Checks and Check Fraud" (PDF). Wachovia Bank. 2003. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2011.

- Cheque and Credit Clearing Company (2009). "Cheques and cheque clearing: An historical perspective" (PDF). p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, The Evolution of the cheque as a Means of Payment: A Historical Survey, 2008. Archived 19 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- History of Cheques Archived 27 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine - Barclays, 2020

- "Domett, Henry Williams. A history of the Bank of New York, 1784-1884 (1884)". 21 July 2010. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- "Newly Discovered Oldest Surviving American chequebook". rarebookbuyer.com. 12 July 2014. Archived from the original on 26 December 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ "Evolution of Payment Systems in India". www.rbi.org.in. 12 December 1998. Archived from the original on 27 April 2006.

- "1 - Progressive Development of the Law of International Trade: Report of the Secretary-General of the United Nations, 1966". www.jus.uio.no. 1966. Archived from the original on 14 September 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ "Uniform Commercial Code § 4-404". Legal Information Institute. United States Congress. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

A bank is under no obligation to a customer having a chequing account to pay a cheque, other than a certified cheque, which is presented more than six months after its date, but it may charge its customer's account for a payment made thereafter in good faith.

- "Cheque Clearing FAQ, question 7". Canadian Payments Association. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- "Legal Issues Guide for Small Business: How long is a cheque valid for?". Department of Innovation, Industry, Science, and Research. 4 July 2008. Archived from the original on 14 September 2010. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- MICR Basics Handbook (PDF). Troy Group. 2015. pp. 1–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 April 2015.

- "SKU: USCST850 MICR 1-1/8" × 8-1/2" Check Correction Strips". U.S. Bank Supply. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- "CPM Federal Credit Union Deposit ATM FAQ". Archived from the original on 16 October 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ "Cheques Working Group Report" (PDF). London: The Office of Fair Trading. November 2006. p. 297. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2009. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- Chandler, Adam (11 September 2024). "It's never been more confusing to pay for something". Sherwood News. Retrieved 12 September 2024.

- "'Green payment' movement set to impact the American payments landscape". euromonitor.com. 4 May 2010. Archived from the original on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- "Why cheques aren't quite dead yet". Financial Times. 30 July 2021.

- "Total number of check payments in 27 countries in Europe from 2000 to 2020". 9 September 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, ed. (2002). The Future of Money. Paris: OECD. pp. 76–79. ISBN 978-92-64-19672-8.

- "2013 Federal Reserve Payments Study". Federal Reserve Bank Services. Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Examining Canadian Payment Methods and Trends" (PDF). Canadian Payment Association. October 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- "Are Australians still using cheques?". 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- "Payment and Settlement Systems in New Zealand". Reserve Bank of New Zealand. March 2008. Retrieved 19 September 2010.

- "Cheque". Glossary of Accounting terms. A-Z-Dictionaries.com. 2005. Archived from the original on 7 March 2009. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- Karp, Paul; Remeikis, Amy (9 March 2020). "Six grants worth a total of $260k approved in marginal seat of Longman before election". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- "Big Cheques". Megaprint Inc. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- "GWR Day - Kuwait: A Really Big cheque". Guinness World Records. 2009. Archived from the original on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- Holden, Lewis (2009). "A cheque is a cheque -- whatever it is printed on". Bankrate, Inc. Archived from the original on 14 September 2010. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- "Paying by Cheque". Payments Canada. 8 August 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- "Standard 006 – Specifications for MICR-Encoded Payment Items" (PDF). Canadian Payments Association. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- "Prohibition of Tele-cheques in the Automated Clearing Settlement System" (PDF). Payments Canada. 1 June 2003. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- "B2B and Mobile Payments: The Road Ahead". Canadian Bankers Association. 7 June 2012. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- "Examining Canadian Payment Methods and Trends" (PDF). Canadian Payment Association. October 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- "Canadian Government is Phasing Out Printed Cheques". businesschief.com. 19 May 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- "Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881". A Lawyers Reference. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- Dubey, Navneet (5 April 2021). "What is Cheque Truncation System and how it benefits you?". mint. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- "CTS - Frequently asked questions | NPCi". www.npci.org.in. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- "India at the bottom of the list: Least reduction in usage of bank cheques". 5 June 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- Homeguard v Kiwi Packaging 2 NZLR 322

- "Payment and Settlement Systems in New Zealand". Reserve Bank of New Zealand. March 2008. Retrieved 19 September 2010.

- "Phasing out of cheques in New Zealand – Are you prepared?". Phasing out of cheques in New Zealand – Are you prepared? | Varntige. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- "The Ministry is phasing out payment by cheque | New Zealand Ministry of Justice".

- Lock, Harry (28 February 2020). "Kiwibank checks out: Last day for customers to use cheques". Radio New Zealand. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- "ASB to phase out use of cheques". Radio New Zealand. 16 May 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- "Çek Kanununda Değişiklik Yapilmasina Dair Kanun" [Law Amending the Cheque Law] (in Turkish). T.C. Resmi Gazete. 3 February 2012.

- Miles, Brignall (30 November 2007). "Cheque changes leave consumers in the clear". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- "R.I.P. Cheque guarantee cards". BBC News. 29 June 2011.

- "Press Releases". Payments Council. Archived from the original on 20 January 2010. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- "Cheques to be phased out in 2018". BBC News. 16 December 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- "Cheques not to be scrapped after all, banks say". BBC News. 12 July 2011.

- "Plans to end cheques criticised by banks". BBC News. 11 December 2010. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- "Popularity of cheques wanes". BBC News. London. 25 July 2002. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- "Shell bans payment by cheque". BBC News. London. 10 September 2005. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- "Cheques get the chop at Asda". The Guardian. London. Press Association. 3 April 2006. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- "High Street retailer bans cheques". BBC News. London. 12 September 2006. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- "2016 UK Payment Statistics" (PDF). Payments UK. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 January 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- "Cheque Market 2018". Cheque and Credit Clearing Company. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ "Cheque Market 2018" (PDF). UK Finance. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 May 2023. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- "Cheque photo plan gets the go-ahead". BBC News. 25 June 2014.

- "UK PAYMENT MARKETS SUMMARY 2022" (PDF). UK Finance. August 2022. p. 6. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- "Image Clearing System". www.wearepay.uk. Pay.uk. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ Cook, Lindsay (30 July 2021). "Why cheques aren't quite dead yet". Financial Times. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- "U.C.C. - Article 3 - Negotiable Iinstruments". Cornell Law School. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ "Inside Check Numbers". Supersat-tech.livejournal.com. Archived from the original on 21 September 2007.

- "X9 TR-2:2005 Understanding, Designing Producing Checks". ANSI. 2005. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- "The Federal Reserve Payments Study - 2018 Annual Supplement". Federal Reserve. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- "2013 Federal Reserve Payments Study". Federal Reserve. Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- Ellis, David (2 December 2009). "17 million Americans have no bank account". CNN News. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- Garner, Bryan A. (1995). A dictionary of modern legal usage (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 953. ISBN 978-0-19-507769-8.

- "Bounced cheques yield libel damages". The Independent. UK. 21 July 1992. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- Tugend, Alina (24 June 2006). "Balancing a Checkbook Isn't Calculus. It's Harder". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- Blake Ellis (16 August 2012). "Bank customers - you're being tracked". CNNMoney. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "CFPB to supervise credit reporting agencies". CNNMoney. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

External links

Media related to cheques at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to cheques at Wikimedia Commons

| Medium of exchange | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commodity money |

| |||||

| Money (Fiat/Token) | ||||||

| General |

| |||||