| This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. Please consider expanding the lead to provide an accessible overview of all important aspects of the article. (October 2023) |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Life in Egypt |

|---|

|

| Culture |

| Society |

| Politics |

| Economy |

|

Egypt portal |

Belly dance (Arabic: رقص شرقي, romanized: Raqs sharqi, lit. 'oriental dance') is a Middle Eastern dance that originated in Egypt, which features movements of the hips and torso. A Western-coined exonym, it is also referred to as Middle Eastern dance or Arabic dance. It has evolved to take many different forms depending on the country and region, both in costume and dance style; with the styles and costumes of Egypt being the most recognized worldwide due to Egyptian cinema. Belly dancing in its various forms and styles is popular across the globe where it is taught by a multitude of schools of dance.

Names and terminology

"Belly dance" is a translation of the French term danse du ventre. The name first appeared in 1864 in a review of the Orientalist painting The Dance of the Almeh by Jean-Léon Gérôme.

The first known use of the term "belly dance" in English is found in Charles James Wills, In the land of the lion and sun: or, Modern Persia (1883).

Raqs sharqi ('Eastern Dance' or 'Dance of the Orient') is a broad category of professional forms of the dance, including forms of belly dance popularly known today, such as Raqs Baladi, Sa'idi, Ghawazee, and Awalim. The informal, social form of the dance is known as Raqs Baladi ('Dance of the Country' or 'Folk Dance') in Egyptian Arabic and is considered an indigenous dance.

Belly dance is primarily a torso-driven dance, with an emphasis on articulations of the hips. Unlike many Western dance forms, the focus of the dance is on isolations of the torso muscles, rather than on movements of the limbs through space. Although some of these isolations appear similar to the isolations used in jazz ballet, they are sometimes driven differently and have a different feeling or emphasis.

Movements found in belly dance

In common with most folk dances, there is no universal naming scheme for belly dance movements. Many dancers and dance schools have developed their own naming schemes, but none of these is universally recognized. The following attempt at categorization reflects the most common naming conventions:

- Percussive: Staccato movements, most commonly of the hips, used to punctuate the music or accent a beat. Lifts or drops of the hips, chest or rib cage, shoulder accents, hip rocks, hits, and twists.

- Fluid: Flowing, sinuous movements in which the body is in continuous motion, used to interpret melodic lines and lyrical sections in the music, or modulated to express complex instrumental improvisations. These movements require a great deal of abdominal muscle control. Typical movements include horizontal and vertical figures of 8 or infinity loops with the hips, horizontal or tilting hip circles, and undulations of the hips and abdomen. These basic shapes may be varied, combined, and embellished to create an infinite variety of complex, textured movements.

- Shimmies, shivers and vibrations: Small, fast, continuous movements of the hips or ribcage, which create an impression of texture and depth of movement. Shimmies are commonly layered over other movements, and are often used to interpret rolls on the tablah or riq or fast strumming of the oud or qanun. There are many types of shimmy, varying in size and method of generation. Some common shimmies include relaxed, up and down hip shimmies, straight-legged knee-driven shimmies, fast, tiny hip vibrations, twisting hip shimmies, bouncing 'earthquake' shimmies, and relaxed shoulder or rib cage shimmies.

In addition to these torso movements, dancers in many styles will use level changes, traveling steps, turns, and spins. The arms are used to frame and accentuate movements of the hips, for dramatic gestures, and to create beautiful lines and shapes with the body. Other movements may be used as occasional accents, such as low kicks and arabesques, backbends, and head tosses.

In the Middle East

Origins and history

Belly dancing is believed to have had a long history in the Middle East. Several Greek and Roman sources including Juvenal and Martial describe dancers from Asia Minor and Spain using undulating movements, playing castanets, and sinking to the floor with "quivering thighs", descriptions that are certainly suggestive of the movements that are today associated with belly dance. Later, particularly in the 18th and 19th centuries, European travellers in the Middle East such as Edward Lane and Flaubert wrote extensively of the dancers they saw there, including the Awalim and Ghawazi of Egypt.

In his book, Andrew Hammond notes that practitioners of the art form agree that belly dance is lodged especially in Egyptian culture, he states: "the Greek historian Herodotus related the remarkable ability of Egyptians to create for themselves spontaneous fun, singing, clapping, and dancing in boats on the Nile during numerous religious festivals. It's from somewhere in this great, ancient tradition of gaiety that the belly dance emerged."

The courtly pleasures of the Umayyad, Abbasid and Fatimid caliphs included belly dancing, soirée and singing. Belly dancers and singers were sent from all parts of the vast empire to entertain. During this era of slavery in the Muslim world, these artists were often slaves. No free woman could perform in public due to the Islamic sex segregation, but female slaves were trained to entertain male guests in singing and other art forms, such as the Qiyan slave artists, who became common during the era of slavery in the Umayyad Caliphate. During the era of slavery in Egypt, female slaves were trained in singing and dancing and given as gifts between men.

In the Ottoman Empire, belly dance was performed by women and later, by boys, in the sultan's palace.

Social context

Belly dance in Egypt has two distinct social contexts: as a folk or social dance.

As a social dance, belly dance (also called Raqs Baladi or Raqs Shaabi in this context) is performed at celebrations and social gatherings by ordinary people (male and female, young and old), in their ordinary clothes. In more conservative or traditional societies, these events may be gender segregated, with separate parties where men and women dance separately.

Historically, professional dance performers were the Awalim (primarily musicians and poets), Ghawazi. The Maazin sisters may have been the last authentic performers of Ghawazi dance in Egypt, with Khayreyya Maazin still teaching and performing as of 2020. Belly dancing is part of Egyptian culture, and is part of Arabic culture as a whole. Throughout the Middle East and the Arab diaspora, belly dancing is closely associated with Arabic music that is modern classical (known as "al-jadid").

In Egypt

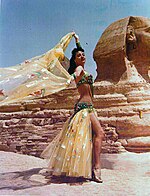

Main article: Raqs sharqi Layla Taj, Egyptian belly dancer, performing in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt

Layla Taj, Egyptian belly dancer, performing in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt

In the 1870s, Shafiqa al-Qibtiyya was the most famous bellydancer in all of Egypt's theatres and casinos, she was admired by the nation and widely celebrated. The modern Egyptian belly dance style and the modern belly dance costumes of the 19th century were featured by the Awalim. For example, many of the dancers in Badia's Casinos went on to appear in Egyptian films and had a great influence on the development of the Egyptian style and became famous, like Samia Gamal and Taheyya Kariokka, both of whom helped attract eyes to the Egyptian style worldwide.

Professional belly dance in Cairo has not been exclusive to native Egyptians, although the country prohibited foreign-born dancers from obtaining licenses for solo work for much of 2004 out of concern that potentially inauthentic performances would dilute its culture. (Other genres of performing arts were not affected.) The ban was lifted in September 2004, but a culture of exclusivity and selectivity remained. The few non-native Egyptians permitted to perform in an authentic way invigorated the dance circuit and helped spread global awareness of the art form. American-born Layla Taj is one example of a non-native Egyptian belly dancer who has performed extensively in Cairo and the Sinai resorts.

Egyptian belly dance is noted for its controlled, precise movements.

Although belly dance is traditionally seen as a feminine art, the number of male belly dancers has increased in recent years.

In Turkey

Belly dance is referred to in Turkey as Oryantal Dans, or simply 'Oryantal' literally meaning orient. Many professional dancers and musicians in Turkey continue to be of Romani heritage, and the Roma people of Turkey have had a strong influence on the Turkish style.

Belly dance in the musical industry

Influence in pop music

Belly dance today is a dance used by various artists among which are Rihanna, Beyoncé, Fergie, however the greatest representative of this dance is the Colombian singer Shakira, who led this dance to position it as her trademark, with her songs Whenever Wherever and Ojos Así, however thanks to the song Hips Don't Lie, her hip dance skills became known worldwide. Also, thanks to Whenever Wherever in 2001, the belly dance fever began popularizing it in a large part of Latin America and later taking it to the United States.

Over time in her presentations Shakira added this dance mixing it with Latin dances, like Salsa and Afro-Colombian, and she also she expressed that she began to dance these movements since she was little thanks to her Lebanese grandmother. Nowadays the belly dance is a characteristic dance of this singer which presented a variant with a rope entangling it in her body and dancing to the rhythm of Whenever Wherever. Shakira is the only artist in the music industry who has used belly dance on several occasions in her artistic career. She inspired Beyoncé to explore this type of dance in her Beautiful Liar collaboration where she also acted as choreographer. At the Super Bowl LIV Halftime Show event she returned to the belly dance with rope during the transition from Ojos así thus to Whenever Wherever.

Outside the Middle East

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Belly dance was popularized in the West during the Romantic movement of the 18th and 19th centuries, when Orientalist artists depicted romanticized images of harem life in the Ottoman Empire.

Belly dancing has become popular outside the Arab world, and American, European, and Japanese women who have become professional belly dancers dance all over Europe and the Middle East.

In North America

Although there were dancers of this type at the 1876 Centennial in Philadelphia, it was not until the 1893 Chicago World's Fair that it gained national attention. The term "belly dancing" is often credited to Sol Bloom, the Fair's entertainment director, but he referred to the dance as danse du ventre, the name used by the French in Algeria. In his memoirs, Bloom states, "when the public learned that the literal translation was "belly dance", they delightedly concluded that it must be salacious and immoral ... I had a gold mine." Authentic dancers from several Middle Eastern and North African countries performed at the Fair, including Syria, Turkey and Algeria—but it was the dancers in the Egyptian Theater of The Street in the Cairo exhibit who gained the most notoriety. The fact that the dancers were uncorseted and gyrated their hips was shocking to Victorian sensibilities. There were no soloists, but it is claimed that a dancer nicknamed Little Egypt stole the show. Some claim the dancer was Farida Mazar Spyropoulos, but this fact is disputed.

The popularity of these dancers subsequently spawned dozens of imitators, many of whom claimed to be from the original troupe. Victorian society continued to be affronted by the dance, and dancers were sometimes arrested and fined. The dance was nicknamed the "hoochie coochie", or the shimmy and shake. A short film, "Fatima's Dance", was widely distributed in the Nickelodeon theaters. It drew criticism for its "immodest" dancing, and was eventually censored. Belly dance drew men in droves to burlesque theaters, and to carnival and circus lots.

Thomas Edison made several films of dancers in the 1890s. These included a Turkish dance, and Crissie Sheridan in 1897, and Princess Rajah from 1904, which features a dancer playing zills, doing "floor work", and balancing a chair in her teeth.

Ruth St. Denis also used Middle Eastern-inspired dance in D. W. Griffith's silent film Intolerance, her goal being to lift dance to a respectable art form at a time when dancers were considered to be women of loose morals. Hollywood began producing films such as The Sheik, Cleopatra, and Salomé, to capitalize on Western fantasies of the orient.

When immigrants from Arab states began to arrive in New York in the 1930s, dancers started to perform in nightclubs and restaurants. In the late 1960s and early 1970s many dancers began teaching. Middle Eastern or Eastern bands took dancers with them on tour, which helped spark interest in the dance.

Although using Turkish and Egyptian movements and music, American Cabaret ("AmCab") belly dancing has developed its own distinctive style, using props and encouraging audience interaction.

In 1987, a distinctively American style of group improvisational dance, American Tribal Style Belly Dance (ATS), was created, representing a major departure from the dance's cultural origins. A unique and wholly modern style, it makes use of steps from existing cultural dance styles, including those from India, the Middle East, and Africa. Many forms of "Tribal Fusion" belly dance have also developed, appropriating elements from many other dance and music styles including flamenco, ballet, burlesque, hula hoop and even hip hop. "Gothic Belly Dance" is a style which incorporates elements from Goth subculture. Continuing from this tradition is the emergence of touring theatrical belly dance productions such as Belly Dance Evolution produced by Jillina Carlano, Invaders of the Heart produced by Myra Krien amongst others.

In Spain

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In Spain and the Iberian Peninsula, the idea of exotic dancing existed throughout the Islamic era and sometimes included slavery. When the Arab Umayyads conquered Spain, they sent Basque singers and dancers to Damascus and Egypt for training in the Middle Eastern style. These dancers came to be known as Al-Andalusian dancers. It is theorized that the fusion of the Al-Andalus style with the dances of the Romani people in Spain led to the creation of flamenco.

In Australia

The first wave of interest in belly dancing in Australia was during the late 1970s to 1980s with the influx of migrants and refugees escaping troubles in the Middle East, including Lebanese Jamal Zraika. These immigrants created a social scene including numerous Lebanese and Turkish restaurants, providing employment for belly dancers. Rozeta Ahalyea is widely regarded as the "mother" of Australian belly dance, training early dance pioneers such as Amera Eid and Terezka Drnzik. Belly dance has now spread across the country, with belly dance communities in every capital city and many regional centres.

Estelle Asmodelle was probably the first transgender belly dancer in Australia. She travelled extensively throughout Asia and Japan working as a Belly Dancer during the 1980s through to the late 1990s. She also starred in the Australian-produced and distributed film The Enchanted Dance which sold internationally as well.

In the United Kingdom

Belly dance has been in evidence in the UK since the early 1960s. During the 1970s and 1980s, there was a thriving Arabic club scene in London, with live Arabic music and belly dancing a regular feature, but the last of these closed in the early 1990s. Several prominent members of the British belly dance community began their dance careers working in these clubs.

Today, there are fewer traditional venues for Arabic dance in the UK; however, there is a large amateur belly dance community. Several international belly dance festivals are now held in Britain such as The International Bellydance Congress, The London Belly Dance Festival and Majma Dance Festival. In addition, there are a growing number of competitions, which have increased in popularity in recent years.

The UK belly dance scene leans strongly towards the Egyptian/Arabic style, with little Turkish influence. American Tribal Style and Tribal Fusion belly dance are also popular.

In Greece

Greek belly dancing is called Tsifteteli, which is Turkish for "double stringed". While the ancient Greek dance Cordax is viewed by some to be the origins of belly dancing in Greece and perhaps the world as a whole, a connection between it and modern Greek belly dancing has yet to be established. Rather, it is generally agreed upon that belly dancing was brought to Greece via Asia Minor refugees during the Greek-Turkish population exchange of 1923. Tsifteteli soon spread across the entirety of Greece and established itself as the most popular Greek dance alongside Zeibekiko. It is characterized by a free form of movement according to the rhythm, without specific rules. It is performed almost exclusively by couples and women.

When danced by a woman "solo", it is usually done on a table full of dishes (so that she cannot take steps, but only shake her chest, waist and buttocks), while the spectators accompany her dancing with rhythmic clapping. The characteristic rhythm is in 8/4 time, arranged as either 3/3/2 eighth-notes followed by 2/2/2/xx (the last beat being silent), or sometimes the first measure is played as 2/2/x1/1x.

Although there is no official dress code associated with the dance itself, professional Greek belly dancers will usually don a complete belly dancing attire in order to emphasize their movements and draw attention to their gyrating body.

In spite of its popularity in the country, there exist a contingent of Greeks that take offense to the existence of the Tsifteteli and call for an end to its performance in Greece. Believing it to not represent Greek ideals and to be a relic of Turkish oppression, they argue it affiliates Greece with the broader Middle East rather than the west which the country supposedly belongs to. These claims, while controversial, are not entirely unfounded considering that the dance is often accompanied by Arabic-sounding music. Regardless of this opposition, the dancing style continues to thrive in Greece, being performed often in every major city.

Costume

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (August 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The costume most commonly associated with belly dance is the 'bedlah' (Arabic: بدلة; literally "suit") style, which typically includes a fitted top or bra, a fitted hip belt, and a full-length skirt or harem pants. The bra and belt may be richly decorated with beads, sequins, crystals, coins, beaded fringe and embroidery. The belt may be a separate piece, or sewn into a skirt.

The costume or bedlah (referring to the bra, belt and skirt), of Egyptian Oriental dancers has also had the distinction as being the most popular style. However, fashions have changed over the years with the help of some outside influences.

Earlier costumes were made up of a full skirt, light chemise and tight cropped vest with heavy embellishments and jewelry.

As well as the two-piece bedlah costume, full-length dresses are sometimes worn, especially when dancing more earthy baladi styles. Dresses range from closely fitting, highly decorated gowns, which often feature heavy embellishments and mesh-covered cutouts, to simpler designs which are often based on traditional clothing.

Costume in Egypt

In Egypt dancers wear the bedlah. Alternatively, some wear folkloric costume inspired by traditional dress. Modest, ethnically-inspired styles with stripes are common, but theatrical variants with mesh-filled cutouts and ornamented with sequins and bead work are also popular. Most dancers complete their costume ensemble with a sparkling hip-scarf. Egypt has laws in place, that require respecting religious and worship places, and disallowing any nudity near sacred places.

Regarding what dancers can and cannot wear, according to Act No. 430 of the law on the censorship of literary works, dancers must cover their upper bodies (mainly the breasts area), and typically a sheer skin-colored mesh fabric covering the stomach is recommended. Many dancers ignore these rules, as they are rarely enforced, and performing in revealing outfits is common in Cairo and locales popular with tourists. Celebrity dancers can earn enough in a single performance to pay fines if/when they are imposed.

Health

Belly dance is a low-impact, weight-bearing exercise and is thus suitable for all ages and levels of fitness. Many of the moves involve isolations, which improves flexibility of the torso. Belly dance moves are beneficial to the spine, as the full-body undulation moves lengthen (decompress) and strengthen the entire column of spinal and abdominal muscles in a gentle way.

Dancing with a veil can help build strength in the upper body, arm and shoulders. Playing the finger cymbals (sagat/zills) trains fingers to work independently and builds strength. The legs and long muscles of the back are strengthened by hip movements.

Notable practitioners

Professional belly dancers include:

- Badia Masabni

- Dalilah

- Didem Kınalı

- Dina Talaat

- Fifi Abdou

- Layla Taj

- Özel Türkbaş

- Nadia Gamal

- Nagwa Fouad

- Nesrin Topkapı

- Naima Akef

- Samia Gamal

- Sema Yildiz

- Serena Wilson

- Soheir Zaki

- Taheyya Kariokka

- Zeinat Olwi

- Nejla Ateş

In popular culture

Egyptian belly dancer and film actress Samia Gamal is credited with bringing belly dancing from Egypt to Hollywood and from there to the schools of Europe. In 1954, she famously starred as a belly dancer in the American Eastmancolor adventure film, Valley of the Kings, and the French film Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.

In British cinema, belly dancing features prominently in several James Bond movies, such as the 1963 movie From Russia With Love, the 1974 movie The Man with the Golden Gun, and the 1977 movie The Spy Who Loved Me.

Belly dancing is quite popular in various parts of the world including India. Belly dancing has been shown in many Bollywood films, and is often accompanied with Bollywood songs and dance sequences instead of the traditional Arabic style.

Hollywood films regularly include sexualized belly dancers as part of Orientalized and exotic depictions of the Middle East.

See also

References

- Britannica Student Encyclopedia. Encyclopedia Britannica. May 2014. ISBN 9781625131720.

- ^ Deagon, Andrea. "Andrea Deagon's Raqs Sharqi".

- Reel, Justine J., ed. (2013). Eating disorders: an encyclopedia of causes, treatment, and prevention. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Greenwood. ISBN 978-1440800580.

- Buonaventura, Wendy (2010). Serpent of the Nile : women and dance in the Arab world ( ed.). London: Saqi. ISBN 978-0863566288.

- Hammond, Andrew (2007). Popular culture in the Arab world : arts, politics, and the media (1. publ. ed.). Cairo, Egypt: American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-9774160547.

- Fraser, Kathleen W. (31 October 2014). Before They Were Belly Dancers: European Accounts of Female Entertainers in Egypt, 1760-1870. McFarland. ISBN 9780786494330.

- Paulsen, Kathryn; Kuhn, Ryan A. (1976). Woman's Almanac: 12 How-to Handbooks in One. Lippincott. p. 544. ISBN 978-0-397-01113-1.

- Hall, G.K. (2002). G.K. Hall Bibliographic Guide to Dance. New York Public Library, Dance Division. Gale Group. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-7838-9648-9.

- Stange, Mary Zeiss; Oyster, Carol K.; Sloan, Jane E. (2013). The Multimedia Encyclopedia of Women in Today's World. SAGE Publications. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-4522-7068-5.

- S.Samir, Twelve Egyptian dancers who created belly dancing, Shafika El Qibtya is the pioneer legendary dancer.

- "Badia Masabani: The Force Behind Modern Belly Dance in Egypt | Egyptian Streets". 21 May 2022. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- "Overview of Belly Dance: Egyptian Folkloric style belly dancing". www.atlantabellydance.com. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- Hawthorn, Ainsley (1 May 2019). "Middle Eastern Dance and What We Call It". Dance Research. 37 (1): 1–17. doi:10.3366/drs.2019.0250. ISSN 0264-2875. S2CID 194311507.

- Hawthorn, Ainsley (23 May 2019). "Why do we call Middle Eastern dance "belly dance"?". Edinburgh University Press Blog.

- "Belly Dance, N." Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford UP. July 2023. doi:10.1093/OED/9972020486.

- Varga Dinicu, Carolena (2011). You Asked Aunt Rocky: Answers & Advice About Raqs Sharqi & Raqs Shaabi. Virginia Beach, VA, USA: RDI Publications, LLC. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-9830690-4-1.

- Wise, Josephine (2012). The JWAAD Book of Bellydance. Croydon, UK: JWAAD Ltd. pp. 60–104. ISBN 978-0-9573105-0-6.

- Buonaventura, Wendy (1989). Serpent of the Nile: Women and Dance in the Arab World. Saqi. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-86356-628-8.

- Hammond, Andrew (2005). Pop Culture Arab world! Media, Arts, and Lifestyle. ABC-CLIO, Inc. p. 235. ISBN 1-85109-449-0.

the Greek historian Herodotus related the remarkable ability of Egyptians to create for themselves spontaneous fun, singing, clapping, and dancing in boats on the Nile during numerous religious festivals. It's from somewhere in this great, ancient tradition of gaiety that the belly dance emerged.

- Da'Mi, Muhammed Al (21 February 2014). Feminizing the West: Neo-Islam's Concepts of Renewal, War and the State. AuthorHouse. ISBN 9781491865231.

- Textiles of Medieval Iberia: Cloth and Clothing in a Multi-cultural Context. (2022). Storbritannien: Boydell Press. p. 180-181

- Fraser, K. W. (2015). Before They Were Belly Dancers: European Accounts of Female Entertainers in Egypt, 1760-1870. USA: McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. 35-36

- "A Question of Köçek – Men in Skirts". Azizasaid. September 2008.

- Wise, Josephine (2012). The JWAAD Book of Bellydance. JWAAD Ltd. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-9573105-0-6.

- Al-Rawi, Rosina Fawzia (1999). Grandmother's Secrets: The Ancient Rituals and Healing Power of Belly Dancing. Interlink Books. pp. 20–22. ISBN 978-1-56656-302-4.

- Gilded Serpent "The Ghawazee: Back from the Brink of Extinction".

- van Nieuwkerk, Karin (1995). A Trade Like Any Other: Female Singers and Dancers in Egypt. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-9774244117.

- Magazine, ProgressME (13 September 2016). "Reclaiming Belly Dancing for Middle Eastern Women". ProgressME Magazine. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- Roginsky, Dina; Rottenberg, Henia (25 November 2019). Moving through Conflict: Dance and Politics in Israel. Routledge. ISBN 9781000750478. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- Martin, Andrew R.; Matthew Mihalka Ph, D. (8 September 2020). Music around the World: A Global Encyclopedia [3 volumes]: A Global Encyclopedia. Abc-Clio. ISBN 9781610694995.

- "تربعت على عرش الرقص ومشى فى جنازتها رجلان ...اسرار فى حياة شفيقة القبطية". June 2021.

- "The "Golden Era" of Belly Dance". Artemisyadancewear.com. 27 March 2020.

- "Bellydance Styles: Egyptian Raqs Sharqi". BellydanceU.net.

- Arvizu, Shannon (2004). "The Politics of Bellydancing in Cairo". The Arab Studies Journal. 12/13 (2/1): 165. JSTOR 27933913.

- Brokaw, Sommer (29 November 2014). "Dancing queen: World-traveled Egyptian dancer to perform here". The Sun. p. 2. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- "buzz words and dancers". Belly Dance Forums. August 2008. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- "'They said men aren't allowed': This male belly dancer is defying gender stereotypes". 30 July 2020.

- Mourat, Elizabeth 'Artemis'. "Turkish Dancing". serpentine.org.

- "Shakira, ¿referente de la danza árabe?". Universidad Piloto de Colombia (in Spanish). 11 November 2020. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- "Shakira Drops Salsa Version Of "Chantaje" Just In Time For Her Birthday". vibe.com. 2 February 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- "El baile de Shakira: cómo ponerte en forma practicándolo". HOLA (in Spanish). 5 September 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- "Recuerdan a Shakira con una cuerda ¡bailando Belly Dance!". Show News (in Mexican Spanish). Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- Wynn, L. L. (January 2010). Pyramids and Nightclubs: A Travel Ethnography of Arab and Western Imaginations of Egypt, from King Tut and a Colony of Atlantis to Rumors of Sex Orgies, Urban Legends about a Marauding Prince, and Blonde Belly Dancers. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292774094.

- Donna Carlton (1995) Looking for Little Egypt. Bloomington, Indiana: International Dance Discovery Books. ISBN 0-9623998-1-7.

- "No More Midway Dancing; Three of the Egyptian Girls Fined $50 Each". The New York Times. 7 December 1893. p. 3. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- "Crissie Sheridan / Thomas A. Edison, Inc". hdl.loc.gov.

- "Princess Rajah dance / American Mutoscope and Biograph Company". hdl.loc.gov.

- "About Tribal Bellydance". Tribalbellydance.org.

- "Starbelly Dancers Announce the World Premiere of International Theatrical Dance Production: The Radiant Tarot".

- "Belly dancer". Retrieved 2 February 2020 – via PressReader.

- "The Enchanted Dance on IMDB". IMDb. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- "The Enchanted Dance". Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- Asmahan of London. "Gilded Serpent, Part 1". Gilded Serpent.

- Asmahan of London. "Gilded Serpent, Part 2". Gilded Serpent. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- "The Annual UK Belly Dance Congress. Randa Kamel and Heather Burby". worldbellydance.com. 23 February 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- "London Belly Dance Festival". Bang Bang Oriental. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- "Majma Dance Festival, Glastonbury dance festival with international stars and the best belly dance teachers". www.majmadance.co.uk. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- "Tsifteteli | Greek belly dance is tsifteteli". 5 October 2010. Retrieved 13 August 2024.

- Wichmann, Anna (29 February 2024). "The Ancient Greek Origins of Zeibekiko and Other Contemporary Dances". Greek Reporter.

- "cordax tsifteteli - Αναζήτηση Google". www.google.com. Retrieved 13 August 2024.

- admin (29 May 2008). "Tsifteteli – Greek form of bellydancing". 5th element.

- "Tsifteteli | Greek belly dance is tsifteteli". 5 October 2010. Retrieved 13 August 2024.

- Artem Uzunov (12 March 2019). Chiftetelli Ciftiteli Chifftatelli | Darbuka Rhythms #11. Retrieved 13 August 2024 – via YouTube.

- "Instagram". www.instagram.com. Retrieved 13 August 2024.

- ^ Eicher, Joanne Bubolz; Ross, Doran H.; Deppe, Margaret (2010). "Snapshot: Dance Costumes". Berg encyclopedia of world dress and fashion. Vol. 1: Africa. New York: Berg. pp. 187–189. ISBN 978-1-84788-390-2.

- "Gilded Serpent".

- Raqs sharqi#Costume

- Article in Egypt Today: Egypt's regulations on belly dancing attire

- Dallal, Tamalyn (2004). Belly Dancing For Fitness. Berkeley: Ulysses Press. ISBN 9781569754108.

- Lo Iacono, Valeria (25 April 2020). "WorldBellydance.com".

- Coluccia, Pina, Anette Paffrath, and Jean Putz. Belly Dancing: The Sensual Art of Energy and Spirit. Rochester, Vt: Park Street Press, 2005

- "Samia Gamal, "The Barefoot Dancer"". 27 March 2020.

- "Belly Dancers".

- "Bollywoods Top 10 Belly Dances". 9 January 2020.

- "Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People. [Documentary Transcript]" (PDF). Directed by Jeremy Earp and Sut Jhally. Written by Jeremy Earp and Jack Shaheen. Media Education Foundation, 60 Masonic St. Northampton, MA 01060. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 August 2016.

External links

Media related to Raqs Sharqi at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Raqs Sharqi at Wikimedia Commons