You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (December 2022) Click for important translation instructions.

|

| Louis Auguste Blanqui | |

|---|---|

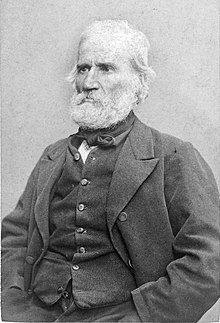

Portrait by his wife, Amelie Serre Blanqui, circa 1835. Portrait by his wife, Amelie Serre Blanqui, circa 1835. | |

| Born | (1805-02-08)8 February 1805 Puget-Théniers, France |

| Died | 1 January 1881(1881-01-01) (aged 75) |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation(s) | Revolutionary, philosopher |

| Known for | Blanquism |

| Father | Jean Dominique Blanqui |

| Relatives | Jérôme-Adolphe Blanqui |

Louis Auguste Blanqui (French pronunciation: [lwi oɡyst blɑ̃ki]; 8 February 1805 – 1 January 1881) was a French socialist, political philosopher and political activist, notable for his revolutionary theory of Blanquism.

Biography

Early life, political activity and first imprisonment (1805–1848)

Blanqui was born in Puget-Théniers, Alpes-Maritimes, where his father, Jean Dominique Blanqui, of Italian descent, was subprefect. He was the younger brother of the liberal economist Jérôme-Adolphe Blanqui. He studied both law and medicine, but found his real vocation in politics, and quickly became a champion of the most advanced opinions. A member of the Carbonari society since 1824, he took an active part in most republican conspiracies during this period. In 1827, under the reign of Charles X (1824–1830), he participated in a street fight in Rue Saint-Denis, during which he was seriously injured. In 1829, he joined Pierre Leroux's Globe newspaper before taking part in the July Revolution of 1830. He then joined the Amis du Peuple ("Friends of the People") society, where he made acquaintances with Philippe Buonarroti, Raspail, and Armand Barbès. He was condemned to repeated terms of imprisonment for maintaining the doctrine of republicanism during the reign of Louis Philippe (1830–1848). During the 1832 trial of the Amis du People at the cour d'assis in Paris Blanqui declared, "You have confiscated the rifles of July--yes. But the bullets have been fired. Every bullet of the workers of Paris is on its way round the world." In May 1839, a Blanquist inspired uprising took place in Paris, in which the League of the Just, forerunners of Karl Marx's Communist League, participated.

Implicated in the armed outbreak of the Société des Saisons, of which he was a leading member, Blanqui was condemned to death on 14 January 1840, a sentence later commuted to life imprisonment.

Release, revolutions and further imprisonment (1848–1879)

He was released during the revolution of 1848, only to resume his attacks on existing institutions. The revolution had not satisfied him. The violence of the Société républicaine centrale, which was founded by Blanqui to demand a change of government, brought him into conflict with the more moderate Republicans, and in 1849 he was sentenced to ten years' imprisonment. While in prison, he sent a brief address (written in the Prison of Belle-Ile-en-Mer, 10 February 1851) to a committee of social democrats in London. The text of the address was noted and introduced by Karl Marx.

In 1865, while serving a further term of imprisonment under the Empire, he escaped, and continued his propaganda campaign against the government from abroad, until the general amnesty of 1869 enabled him to return to France. Blanqui's predilection for violence was illustrated in 1870 by two unsuccessful armed demonstrations: one on 12 January at the funeral of Victor Noir, the journalist shot by Pierre Bonaparte; the other on 14 August, when he led an attempt to seize some guns from a barracks. Upon the fall of the Empire, through the revolution of 4 September, Blanqui established the club and journal La patrie en danger.

He was one of the group that briefly seized the reins of power on 31 October and for his share in that outbreak he was again condemned to death in absentia on 9 March of the following year. On 17 March, Adolphe Thiers, aware of the threat represented by Blanqui, took advantage of his resting at a friend physician's place, in Bretenoux in Lot, and had him arrested. A few days afterwards the insurrection which established the Paris Commune broke out, and Blanqui was elected president of the insurgent commune. The Communards offered to release all of their prisoners if the Thiers government released Blanqui, but their offer was met with refusal, and Blanqui was thus prevented from taking an active part. Karl Marx would later be convinced that Blanqui was the leader that was missed by the Commune. Nevertheless, in 1872 he was condemned along with the other members of the Commune to transportation; on account of his broken health this sentence was again commuted to one of imprisonment. On 20 April 1879 he was elected a deputy for Bordeaux; although the election was pronounced invalid, Blanqui was freed, and immediately resumed his work of agitation.

Ideology

Main article: BlanquismAs a socialist, Blanqui favored what he described as a just redistribution of wealth. However, Blanquism is distinguished in various ways from other socialist currents of the day. On one side, contrary to Karl Marx, Blanqui did not believe in the preponderant role of the working class, nor in popular movements: he thought, on the contrary, that the revolution should be carried out by a small group, who would establish a temporary dictatorship by force. This period of transitional tyranny would permit the implementation of the basis of a new order, after which power would be handed to the people. In another respect, Blanqui was more concerned with the revolution itself than with the future society that would result from it: if his thought was based on precise socialist principles, it rarely goes so far as to imagine a society purely and really socialist. In this he differs from the utopian socialists. For the Blanquists, the overturning of the bourgeois social order and the revolution are ends sufficient in themselves, at least for their immediate purposes. He was one of the non-Marxist socialists of his day.

Death

Following a speech at a political meeting in Paris, Blanqui had a stroke. He died on 1 January 1881 and was interred in the Père Lachaise Cemetery. His elaborate tomb was created by Jules Dalou.

Legacy

Blanqui's uncompromising radicalism, and his determination to enforce it by violence, brought him into conflict with every French government during his lifetime, and as a consequence, he spent half of his life in prison. Besides his innumerable contributions to journalism, he published a work entitled, L'Eternité par les astres (1872), where he espoused his views concerning eternal return. After his death his writings on economic and social questions were collected under the title of Critique sociale (1885).

The Italian fascist newspaper Il Popolo d'Italia, founded and edited by Benito Mussolini, had a quotation by Blanqui on its mast: Chi ha del ferro ha del pane ("He who has iron has bread").

Blanqui's political activism and his book L'Eternité par les astres were commented on by Walter Benjamin in his Arcades Project and are referred to in the novel The Secret Knowledge by Andrew Crumey.

See also

Works

French

- L'Armée esclave et opprimée

- Critique sociale: Capital et travail

- Critique sociale: Fragments et notes

- Instructions pour une prise d'armes.

- Maintenant il faut des armes

- Ni dieu ni maitre

- Qui fait la soupe doit la manger

- Réponse

- Un dernier mot

English translations

- The Eternity According to the Stars, tr. by Mathew H. Anderson, with an afterword by Lisa Block de Behar ("Literary Escapes and Astral Shelters of an Incarcerated Conspirator"). In CR: The New Centennial Review 9/3: 61–94, Winter 2009. The first full-length translation into English.

- Eternity by the Stars. Frank Chouraqui, trans. New York: Contra Mundum Press, 2013.

Footnotes

- Berna, Henri (2010). Du socialisme utopique au socialisme ringard. Paris: Mon Petit Editeur. p. 54. ISBN 978-2-7483-5392-1. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- Benjamin, Walter (1999). Tiedemann, Rolf (ed.). The Arcades Project. Translated by Eiland, Howard; McLaughlin, Kevin. Cambridge (MA): The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 735. ISBN 0674008022.

- Blanqui, Auguste (1805-1881) Auteur du texte (1832). Défense du citoyen Louis Auguste Blanqui devant la Cour d'assises : 1832 (in French). p. 14.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Introduction to the Leaflet of L. A. Blanqui's Toast Sent to the Refugee Committee, written at the prison of Belle-Ile-en-Mer, 10 February 1851, hosted at Marxists.org, last retrieved 25 April 2007

- Christopher Hibbert, Mussolini: The Rise and Fall of Il Duce, New York: NY, St. Martin’s Press, 2008, p. 21. First published in 1962 as Il Duce: The Life of Benito Mussolini

- "Editors' Note".

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Blanqui, Louis Auguste". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Blanqui, Louis Auguste". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- Mitchell Abidor (trans.), Communards: The Story of the Paris Commune of 1871 as Told by Those Who Fought for It. Pacifica, CA: Marxists Internet Archive, 2010.

- Doug Enaa Greene, Communist Insurgent: Blanqui's Politics of Revolution. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2017.

- Patrick H. Hutton, The Cult of the Revolutionary Tradition: The Blanquists in French Politics, 1864-1893. Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 1981

- Nomad, Max (1961) . "The Martyr: Auguste Blanqui, the Glorious Prisoner". Apostles of Revolution. New York: Collier Books. pp. 21–82. LCCN 61018566. OCLC 984463383.

External links

- Louis-Auguste Blanqui Archive at Marxists Internet Archive

- The Blanqui Archive at Kingston University

| Social philosophy | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concepts |

| ||||||||||

| Schools | |||||||||||

| Philosophers |

| ||||||||||

| Works |

| ||||||||||

| See also | |||||||||||

- 1805 births

- 1881 deaths

- People from Alpes-Maritimes

- French people of Italian descent

- Politicians from Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur

- French socialists

- Members of the 2nd Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic

- French activists

- Revolution theorists

- Carbonari

- French people of the Revolutions of 1848

- People of the Paris Commune

- People sentenced to death in absentia

- French prisoners sentenced to death

- Prisoners sentenced to death by France

- Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery

- Activists from Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur