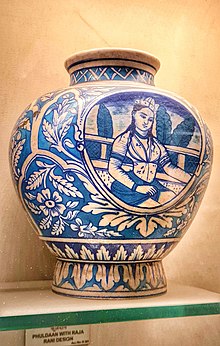

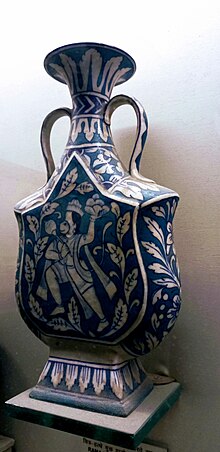

Blue pottery is widely recognized as a traditional craft of Jaipur of Central Asian origin. The name 'blue pottery' comes from the eye-catching cobalt blue dye used to colour the pottery. It is one of many Eurasian types of blue and white pottery, and related in the shapes and decoration to Islamic pottery and, more distantly, Chinese pottery.

Jaipur blue pottery has been strongly influenced by the Persian ceramic style but it has developed its own designs and motifs. Inspired more from nature, the pottery is adorned profusely with animals, birds and flowers with a hint of Persian geometric design in the compositions. Some of this pottery is semi-transparent and mostly decorated with Mughal arabesque patterns and bird and other animal motifs, a design forbidden in Persian art of Islamic origin.

Jaipur blue pottery, made out of ceramic frit material similar to Egyptian faience, is glazed and low-fired. No clay is used: the 'dough' for the pottery is prepared by mixing quartz stone powder, powdered glass, multani mitti (fuller's earth), borax, gum and water. Another source cites Katira Gond powder (a gum), and saaji (soda bicarbonate) as ingredients. Like pottery it is fired only once. The biggest advantage is that blue pottery does not develop any cracks, and blue pottery is also impervious, hygienic, and suitable for daily use. Blue pottery is beautifully decorated with the brush when the pot is rotated. Thus it has great utilitarian as well as aesthetic significance.

Being fired at very low temperature makes them fragile. The range of items is primarily decorative, such as ashtrays, vases, coasters, small bowls and boxes for trinkets. The colour palette is restricted to blue derived from the cobalt oxide, green from the copper oxide and white, though other non-conventional colours, such as yellow and brown are sometimes included. The products made include plates, flower vases, soap dishes, surahis (small pitcher), trays, coasters, fruit bowls, door knobs, and glazed tiles with hand painted floral designs. Sometimes, designer pieces for display are also made. The craft is found mainly in Jaipur, but also in Sanganer, Mahalan, and Neota.

History

The use of blue glaze on pottery is an imported technique, first developed by Mongol artisans who combined Chinese glazing technology with Persian decorative arts. This technique traveled east to India with early Turkic conquests in the 14th century. During its infancy, it was used to make tiles to decorate mosques, tombs and palaces in Central Asia. Later, following their conquests and arrival in India, the Mughals began using them in India. Gradually the blue glaze technique grew beyond an architectural accessory to Indian potters. From there, the technique traveled to the plains of Delhi and in the 17th century went to Jaipur.

Other accounts of the craft state that blue pottery came to Jaipur in the early 19th century under the ruler Sawai Ram Singh II (1835–1880). The Jaipur king had sent local artisans to Delhi to be trained in the craft. Some specimens of older ceramic work can be seen in the Rambagh Palace, where the fountains are lined with blue tiles. Sawai Ram Singh, in his reign (1835–1880), promoted art in Jaipur state with dedication. Legend says that impressed by the art of blue pottery, he brought artists from Delhi to Jaipur. However, Jaipur blue pottery introduced original innovations and mastered the art in such a way that it was claimed to have surpassed the Delhi pottery. Back in 1916, The Journal of Indian Art recorded that Jaipur ware was an improvement upon Delhi pottery. His successor Sawai Madho Singh patronized an exhibition of industrial arts and crafts in 1883 in which finest blue pottery pieces were exhibited with other arts and crafts. Prized possessions of the exhibition were displayed in a museum like space in the exhibition. Many of artisans had been trained in the school of art opened by Sawai Ram Singh and the then director of the school, Opendronath Sen, who had worked particularly to promote the blue pottery, was also happy to see it being showcased in the exhibition. Jaipur School indigenised the art of Blue Pottery through designs that were drawn from Indian life like Indian animals, Hindu deities, Indian human figures, features of Indian palaces etc.

However, by the 1950s, blue pottery had all but vanished from Jaipur, when it was re-introduced through the efforts of the muralist and painter Kripal Singh Shekhawat, with the support of patrons such as Kamladevi Chattopadhaya and Rajmata Gayatri Devi. Today, blue pottery is an industry that provides livelihood to many people in Jaipur. Jaipur blue pottery, despite new innovations in vessels and designs, has retained the traditional blue and adheres to the traditional motifs rendering it instantly recognisable. The fountains inside the Polo Bar and the Maharani Suite within the Rambagh Palace complex are examples of some of the finest craftsmanship of Jaipur Blue Pottery and evidence the support of royal patronage to the art.

Process

Making blue pottery is a complex and time-intensive procedure and is done in many steps. Being fired at very low temperature makes the process a fragile one, fraught with risks and requires practice, patience, and expertise. The absence of clay is what distinguishes blue pottery from traditional pottery. The materials used to make blue pottery are quartz stone powder, powdered glass, borax, gum, and Multani mitti (fuller's earth). They are kneaded into a dough by mixing together and adding water. The moulding dough is rolled and flattened into a 4–5 millimetre thick 'Chapatti' (pancake) and placed in moulds with a mixture of pebbles and ash. Moulds, made from Plaster of Paris (POP), are maintained with care to enable multiple use. The mould is turned upside down and removed and the product is left for drying for 1–2 days. After cleaning and shaping the pottery, the surface is polished with sandpaper. This step smoothens the product and makes it ready for painting. After painting motifs over it and adding a final coat of glaze, the fully dried product is ready to get in furnace.

The artisans traditionally used to offer prayers before they would set up the furnace. Some artists even today continue the practice to pray for successful baking of pottery. Preparing a furnace for the firing of the pottery is a delicate process, and any misstep can lead to cracks in the product. The products are kept inside a furnace to dry. For approximately 4–5 hours firing of the pieces takes place with meticulous care to maintain even temperatures to avert any cracks. Before taking out the products, the artisans wait for the kiln to cool off completely. It might take 2–3 days before the products can be taken out. The finished products are lightly cleaned before they are showcased or packaged.

Revival

Jaipur's blue pottery has evolved significantly in terms of materials, styles, and forms. The raw materials used and making processes have changed over the years. Previously, the glazed coating used on pottery contained lead but an increasing awareness of harmful effects has led to lead-free production. In many places, diesel furnaces are being used instead of traditional wood or charcoal-fueled kilns. Even the designs and motifs are moving away from classical repertoire to cater to modern sensibilities and market demands. The revival of Jaipur blue pottery art owes a lot to the artist Kripal Singh Shekhawat. Seeing the dwindling interest in the art, and deplorable state of the artists, he made it his mission in reviving the art. He garnered the support of Maharani Gayatri Devi of Jaipur and others to give a fillip to the dying art of Jaipur blue pottery.

In its new lease of life many blue pottery shops and training schools have sprung up in Jaipur. Kripal Kumbh, the pottery studio founded by Kripal Singh Shekhawat is still in operation. Established in 1995, Rural Non-farm Development Agency (RUDA) aims to promote artisans of Rajasthan at the global level has also contributed to promote blue pottery of Jaipur. Leela Bordia with ceramic training from US extended the art of blue pottery to beads, necklace, pendants and other ornament-like items. Her inventory also included items like tiles, bathroom fittings etc. that gained popularity with interior decorators. It has been suggested that to revive and promote the art of blue pottery, sustained efforts are required to train the artists to use standardized tools, diversify into utility products by moving beyond decorative ones, and to assist and enable marketing avenues.

A notable training center in Jaipur is Sawai Ram Singh Shilp Kala Mandir, but many artists also conduct short training programmes at their workshops to sustain the legacy of Jaipur blue pottery.

References

- ^ Subodh Kapoor (2002). "Blue Pottery of Jaipur". The Indian Encyclopaedia. Cosmo Publications. p. 935. ISBN 978-81-7755-257-7. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ Taknet, DK (July 2016). Jaipur: Gem of India. IntegralDMS. ISBN 9781942322054.

- "Craftmark Certified Processes: Blue Pottery". All India Artisans and Craftworkers Welfare Association. Archived from the original on 23 July 2015.

- "Blue Pottery - Rajasthan Industries". Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- Museum, Alankar (2011). Tryst with Tradition: Exploring Rajasthan Through the Alankar Museum, Jawahar Kala Kendra. Jawahar Kala Kendra.

- "Blue Pottery - Rajasthan Industires". Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ Subodh Kapoor. "6". Statement of Case for Blue Pottery of Jaipur in Rajasthan (PDF). Govt. of India. p. 25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Notes on Jaipur Pottery. The Journal of Indian Art, 1886-1916; London Vol. 17, Iss. 129-136, (Oct 1916): 27–34.

- Tillotson, G. (2004). The Jaipur Exhibition of 1883. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 14(2), 111–126.

- Tillotson, G. (2004). The Jaipur Exhibition of 1883. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 14(2), 111–126.

- "Blue Pottery" (PDF). All India Artisans and Craftworkers Welfare Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 August 2015.

- shubhangi (4 March 2016). "Making Process". D'Source. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- "Colour me bright & blue". Deccan Herald. 20 February 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- Gupta, Anil K. (2002). "A Historical and Artistic Study of the Blue Pottery of Jaipur". Interceram: International Ceramic Review. 51 (6): 400–403. ISSN 0020-5214. S2CID 190196201.

- "Blue Pottery by BIJO JOSEPH PURACKAL - Issuu". issuu.com. 18 June 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2022.