In atomic physics, the Bohr model or Rutherford–Bohr model was the first successful model of the atom. Developed from 1911 to 1918 by Niels Bohr and building on Ernest Rutherford's nuclear model, it supplanted the plum pudding model of J J Thomson only to be replaced by the quantum atomic model in the 1920s. It consists of a small, dense nucleus surrounded by orbiting electrons. It is analogous to the structure of the Solar System, but with attraction provided by electrostatic force rather than gravity, and with the electron energies quantized (assuming only discrete values).

In the history of atomic physics, it followed, and ultimately replaced, several earlier models, including Joseph Larmor's Solar System model (1897), Jean Perrin's model (1901), the cubical model (1902), Hantaro Nagaoka's Saturnian model (1904), the plum pudding model (1904), Arthur Haas's quantum model (1910), the Rutherford model (1911), and John William Nicholson's nuclear quantum model (1912). The improvement over the 1911 Rutherford model mainly concerned the new quantum mechanical interpretation introduced by Haas and Nicholson, but forsaking any attempt to explain radiation according to classical physics.

The model's key success lies in explaining the Rydberg formula for hydrogen's spectral emission lines. While the Rydberg formula had been known experimentally, it did not gain a theoretical basis until the Bohr model was introduced. Not only did the Bohr model explain the reasons for the structure of the Rydberg formula, it also provided a justification for the fundamental physical constants that make up the formula's empirical results.

The Bohr model is a relatively primitive model of the hydrogen atom, compared to the valence shell model. As a theory, it can be derived as a first-order approximation of the hydrogen atom using the broader and much more accurate quantum mechanics and thus may be considered to be an obsolete scientific theory. However, because of its simplicity, and its correct results for selected systems (see below for application), the Bohr model is still commonly taught to introduce students to quantum mechanics or energy level diagrams before moving on to the more accurate, but more complex, valence shell atom. A related quantum model was proposed by Arthur Erich Haas in 1910 but was rejected until the 1911 Solvay Congress where it was thoroughly discussed. The quantum theory of the period between Planck's discovery of the quantum (1900) and the advent of a mature quantum mechanics (1925) is often referred to as the old quantum theory.

Background

Main article: History of atomic theory

Until the second decade of the 20th century, atomic models were generally speculative. Even the concept of atoms, let alone atoms with internal structure, faced opposition from some scientists.

Planetary models

In the late 1800s speculations on the possible structure of the atom included planetary models with orbiting charged electrons. These models faced a significant constraint. In 1897, Joseph Larmor showed that an accelerating charge would radiate power according to classical electrodynamics, a result known as the Larmor formula. Since electrons forced to remain in orbit are continuously accelerating, they would be mechanically unstable. Larmor noted that electromagnetic effect of multiple electrons, suitable arranged, would cancel each other. Thus subsequent atomic models based on classical electrodynamics needed to adopt such special multi-electron arrangements.

Thomson's atom model

Main article: Plum pudding modelWhen Bohr began his work on a new atomic theory in the summer of 1912 the atomic model proposed by J J Thomson, now known as the Plum pudding model, was the best available. Thomson proposed a model with electrons rotating in coplanar rings within an atomic-sized, positively-charged, spherical volume. Thomson showed that this model was mechanically stable by lengthy calculations and was electrodynamically stable under his original assumption of thousands of electrons per atom. Moreover, he suggested that the particularly stable configurations of electrons in rings was connected to chemical properties of the atoms. He developed a formula for the scattering of beta particles that seemed to match experimental results. However Thomson himself later showed that the atom had a factor of a thousand fewer electrons, challenging the stability argument and forcing the poorly understood positive sphere to have most of the atom's mass. Thomson was also unable to explain the many lines in atomic spectra.

Rutherford nuclear model

Main articles: Rutherford atom and Rutherford scattering experimentsIn 1908, Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden demonstrated that alpha particle occasionally scatter at large angles, a result inconsistent with Thomson's model. In 1911 Ernest Rutherford developed a new scattering model, showing that the observed large angle scattering could be explained by a compact, highly charged mass at the center of the atom. Rutherford scattering did not involve the electrons and thus his model of the atom was incomplete. Bohr begins his first paper on his atomic model by describing Rutherford's atom as consisting of a small, dense, positively charged nucleus attracting negatively charged electrons.

Atomic spectra

By the early twentieth century, it was expected that the atom would account for the many atomic spectral lines. These lines were summarized in empirical formula by Johann Balmer and Johannes Rydberg. In 1897, Lord Rayleigh showed that vibrations of electrical systems predicted spectral lines that depend on the square of the vibrational frequency, contradicting the empirical formula which depended directly on the frequency. In 1907 Arthur W. Conway showed that, rather than the entire atom vibrating, vibrations of only one of the electrons in the system described by Thomson might be sufficient to account for spectral series. Although Bohr's model would also rely on just the electron to explain the spectrum, he did not assume an electrodynamical model for the atom.

The other important advance in the understanding of atomic spectra was the Rydberg–Ritz combination principle which related atomic spectral line frequencies to differences between 'terms', special frequencies characteristic of each element. Bohr would recognize the terms as energy levels of the atom divided by the Planck constant, leading to the modern view that the spectral lines result from energy differences.

Haas atomic model

In 1910, Arthur Erich Haas proposed a model of the hydrogen atom with an electron circulating on the surface of a sphere of positive charge. The model resembled Thomson's plum pudding model, but Haas added a radical new twist: he constrained the electron's potential energy, , on a sphere of radius a to equal the frequency, f, of the electron's orbit on the sphere times the Planck constant: where e represents the charge on the electron and the sphere. Haas combined this constraint with the balance-of-forces equation. The attractive force between the electron and the sphere balances the centrifugal force: where m is the mass of the electron. This combination relates the radius of the sphere to the Planck constant: Haas solved for the Planck constant using the then-current value for the radius of the hydrogen atom. Three years later, Bohr would use similar equations with different interpretation. Bohr took the Planck constant as given value and used the equations to predict, a, the radius of the electron orbiting in the ground state of the hydrogen atom. This value is now called the Bohr radius.

Influence of the Solvay Conference

The first Solvay Conference, in 1911, was one of the first international physics conferences. Nine Nobel or future Nobel laureates attended, including Ernest Rutherford, Bohr's mentor. Bohr did not attend but he read the Solvay reports and discussed them with Rutherford.

The subject of the conference was the theory of radiation and the energy quanta of Max Planck's oscillators. Planck's lecture at the conference ended with comments about atoms and the discussion that followed it concerned atomic models. Hendrik Lorentz raised the question of the composition of the atom based on Haas's model, a form of Thomson's plum pudding model with a quantum modification. Lorentz explained that the size of atoms could be taken to determine the Planck constant as Haas had done or the Planck constant could be taken as determining the size of atoms. Bohr would adopt the second path.

The discussions outlined the need for the quantum theory to be included in the atom. Planck explicitly mentions the failings of classical mechanics. While Bohr had already expressed a similar opinion in his PhD thesis, at Solvay the leading scientists of the day discussed a break with classical theories. Bohr's first paper on his atomic model cites the Solvay proceedings saying: "Whatever the alteration in the laws of motion of the electrons may be, it seems necessary to introduce in the laws in question a quantity foreign to the classical electrodynamics, i.e. Planck's constant, or as it often is called the elementary quantum of action." Encouraged by the Solvay discussions, Bohr would assume the atom was stable and abandon the efforts to stabilize classical models of the atom

Nicholson atom theory

In 1911 John William Nicholson published a model of the atom which would influence Bohr's model. Nicholson developed his model based on the analysis of astrophysical spectroscopy. He connected the observed spectral line frequencies with the orbits of electrons in his atoms. The connection he adopted associated the atomic electron orbital angular momentum with the Planck constant. Whereas Planck focused on a quantum of energy, Nicholson's angular momentum quantum relates to orbital frequency. This new concept gave Planck constant an atomic meaning for the first time. In his 1913 paper Bohr cites Nicholson as finding quantized angular momentum important for the atom.

The other critical influence of Nicholson work was his detailed analysis of spectra. Before Nicholson's work Bohr thought the spectral data was not useful for understanding atoms. In comparing his work to Nicholson's, Bohr came to understand the spectral data and their value. When he then learned from a friend about Balmer's compact formula for the spectral line data, Bohr quickly realized his model would match it in detail.

Nicholson's model was based on classical electrodynamics along the lines of J.J. Thomson's plum pudding model but his negative electrons orbiting a positive nucleus rather than circulating in a sphere. To avoid immediate collapse of this system he required that electrons come in pairs so the rotational acceleration of each electron was matched across the orbit. By 1913 Bohr had already shown, from the analysis of alpha particle energy loss, that hydrogen had only a single electron not a matched pair. Bohr's atomic model would abandon classical electrodynamics.

Nicholson's model of radiation was quantum but was attached to the orbits of the electrons. Bohr quantization would associate it with differences in energy levels of his model of hydrogen rather than the orbital frequency.

Bohr's previous work

Bohr completed his PhD in 1911 with a thesis 'Studies on the Electron Theory of Metals', an application of the classical electron theory of Hendrik Lorentz. Bohr noted two deficits of the classical model. The first concerned the specific heat of metals which James Clerk Maxwell noted in 1875: every additional degree of freedom in a theory of metals, like subatomic electrons, cause more disagreement with experiment. The second, the classical theory could not explain magnetism.

After his PhD, Bohr worked briefly in the lab of JJ Thomson before moving to Rutherford's lab in Manchester to study radioactivity. He arrived just after Rutherford completed his proposal of a compact nuclear core for atoms. Charles Galton Darwin, also at Manchester, had just completed an analysis of alpha particle energy loss in metals, concluding the electron collisions where the dominant cause of loss. Bohr showed in a subsequent paper that Darwin's results would improve by accounting for electron binding energy. Importantly this allowed Bohr to conclude that hydrogen atoms have a single electron.

Development

Next, Bohr was told by his friend, Hans Hansen, that the Balmer series is calculated using the Balmer formula, an empirical equation discovered by Johann Balmer in 1885 that described wavelengths of some spectral lines of hydrogen. This was further generalized by Johannes Rydberg in 1888, resulting in what is now known as the Rydberg formula. After this, Bohr declared, "everything became clear".

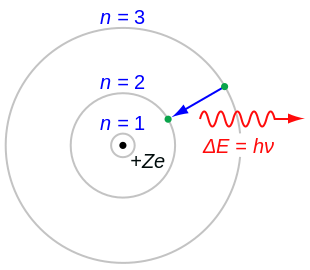

In 1913 Niels Bohr put forth three postulates to provide an electron model consistent with Rutherford's nuclear model:

- The electron is able to revolve in certain stable orbits around the nucleus without radiating any energy, contrary to what classical electromagnetism suggests. These stable orbits are called stationary orbits and are attained at certain discrete distances from the nucleus. The electron cannot have any other orbit in between the discrete ones.

- The stationary orbits are attained at distances for which the angular momentum of the revolving electron is an integer multiple of the reduced Planck constant: , where is called the principal quantum number, and . The lowest value of is 1; this gives the smallest possible orbital radius, known as the Bohr radius, of 0.0529 nm for hydrogen. Once an electron is in this lowest orbit, it can get no closer to the nucleus. Starting from the angular momentum quantum rule as Bohr admits is previously given by Nicholson in his 1912 paper, Bohr was able to calculate the energies of the allowed orbits of the hydrogen atom and other hydrogen-like atoms and ions. These orbits are associated with definite energies and are also called energy shells or energy levels. In these orbits, the electron's acceleration does not result in radiation and energy loss. The Bohr model of an atom was based upon Planck's quantum theory of radiation.

- Electrons can only gain and lose energy by jumping from one allowed orbit to another, absorbing or emitting electromagnetic radiation with a frequency determined by the energy difference of the levels according to the Planck relation: , where is the Planck constant.

Other points are:

- Like Einstein's theory of the photoelectric effect, Bohr's formula assumes that during a quantum jump a discrete amount of energy is radiated. However, unlike Einstein, Bohr stuck to the classical Maxwell theory of the electromagnetic field. Quantization of the electromagnetic field was explained by the discreteness of the atomic energy levels; Bohr did not believe in the existence of photons.

- According to the Maxwell theory the frequency of classical radiation is equal to the rotation frequency rot of the electron in its orbit, with harmonics at integer multiples of this frequency. This result is obtained from the Bohr model for jumps between energy levels and when is much smaller than . These jumps reproduce the frequency of the -th harmonic of orbit . For sufficiently large values of (so-called Rydberg states), the two orbits involved in the emission process have nearly the same rotation frequency, so that the classical orbital frequency is not ambiguous. But for small (or large ), the radiation frequency has no unambiguous classical interpretation. This marks the birth of the correspondence principle, requiring quantum theory to agree with the classical theory only in the limit of large quantum numbers.

- The Bohr–Kramers–Slater theory (BKS theory) is a failed attempt to extend the Bohr model, which violates the conservation of energy and momentum in quantum jumps, with the conservation laws only holding on average.

Bohr's condition, that the angular momentum be an integer multiple of , was later reinterpreted in 1924 by de Broglie as a standing wave condition: the electron is described by a wave and a whole number of wavelengths must fit along the circumference of the electron's orbit:

According to de Broglie's hypothesis, matter particles such as the electron behave as waves. The de Broglie wavelength of an electron is

which implies that

or

where is the angular momentum of the orbiting electron. Writing for this angular momentum, the previous equation becomes

which is Bohr's second postulate.

Bohr described angular momentum of the electron orbit as while de Broglie's wavelength of described divided by the electron momentum. In 1913, however, Bohr justified his rule by appealing to the correspondence principle, without providing any sort of wave interpretation. In 1913, the wave behavior of matter particles such as the electron was not suspected.

In 1925, a new kind of mechanics was proposed, quantum mechanics, in which Bohr's model of electrons traveling in quantized orbits was extended into a more accurate model of electron motion. The new theory was proposed by Werner Heisenberg. Another form of the same theory, wave mechanics, was discovered by the Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger independently, and by different reasoning. Schrödinger employed de Broglie's matter waves, but sought wave solutions of a three-dimensional wave equation describing electrons that were constrained to move about the nucleus of a hydrogen-like atom, by being trapped by the potential of the positive nuclear charge.

Electron energy levels

The Bohr model gives almost exact results only for a system where two charged points orbit each other at speeds much less than that of light. This not only involves one-electron systems such as the hydrogen atom, singly ionized helium, and doubly ionized lithium, but it includes positronium and Rydberg states of any atom where one electron is far away from everything else. It can be used for K-line X-ray transition calculations if other assumptions are added (see Moseley's law below). In high energy physics, it can be used to calculate the masses of heavy quark mesons.

Calculation of the orbits requires two assumptions.

- Classical mechanics

- The electron is held in a circular orbit by electrostatic attraction. The centripetal force is equal to the Coulomb force.

- where me is the electron's mass, e is the elementary charge, ke is the Coulomb constant and Z is the atom's atomic number. It is assumed here that the mass of the nucleus is much larger than the electron mass (which is a good assumption). This equation determines the electron's speed at any radius:

- It also determines the electron's total energy at any radius:

- The total energy is negative and inversely proportional to r. This means that it takes energy to pull the orbiting electron away from the proton. For infinite values of r, the energy is zero, corresponding to a motionless electron infinitely far from the proton. The total energy is half the potential energy, the difference being the kinetic energy of the electron. This is also true for noncircular orbits by the virial theorem.

- A quantum rule

- The angular momentum L = mevr is an integer multiple of ħ:

Derivation

In classical mechanics, if an electron is orbiting around an atom with period T, and if its coupling to the electromagnetic field is weak, so that the orbit doesn't decay very much in one cycle, it will emit electromagnetic radiation in a pattern repeating at every period, so that the Fourier transform of the pattern will only have frequencies which are multiples of 1/T.

However, in quantum mechanics, the quantization of angular momentum leads to discrete energy levels of the orbits, and the emitted frequencies are quantized according to the energy differences between these levels. This discrete nature of energy levels introduces a fundamental departure from the classical radiation law, giving rise to distinct spectral lines in the emitted radiation.

Bohr assumes that the electron is circling the nucleus in an elliptical orbit obeying the rules of classical mechanics, but with no loss of radiation due to the Larmor formula.

Denoting the total energy as E, the negative electron charge as e, the positive nucleus charge as K=Z|e|, the electron mass as me, half the major axis of the ellipse as a, he starts with these equations:

E is assumed to be negative, because a positive energy is required to unbind the electron from the nucleus and put it at rest at an infinite distance.

Eq. (1a) is obtained from equating the centripetal force to the Coulombian force acting between the nucleus and the electron, considering that (where T is the average kinetic energy and U the average electrostatic potential), and that for Kepler's second law, the average separation between the electron and the nucleus is a.

Eq. (1b) is obtained from the same premises of eq. (1a) plus the virial theorem, stating that, for an elliptical orbit,

Then Bohr assumes that is an integer multiple of the energy of a quantum of light with half the frequency of the electron's revolution frequency, i.e.:

From eq. (1a,1b,2), it descends:

He further assumes that the orbit is circular, i.e. , and, denoting the angular momentum of the electron as L, introduces the equation:

Eq. (4) stems from the virial theorem, and from the classical mechanics relationships between the angular momentum, the kinetic energy and the frequency of revolution.

From eq. (1c,2,4), it stems:

where:

that is:

This results states that the angular momentum of the electron is an integer multiple of the reduced Planck constant.

Substituting the expression for the velocity gives an equation for r in terms of n:

so that the allowed orbit radius at any n is

The smallest possible value of r in the hydrogen atom (Z = 1) is called the Bohr radius and is equal to:

The energy of the n-th level for any atom is determined by the radius and quantum number:

An electron in the lowest energy level of hydrogen (n = 1) therefore has about 13.6 eV less energy than a motionless electron infinitely far from the nucleus. The next energy level (n = 2) is −3.4 eV. The third (n = 3) is −1.51 eV, and so on. For larger values of n, these are also the binding energies of a highly excited atom with one electron in a large circular orbit around the rest of the atom. The hydrogen formula also coincides with the Wallis product.

The combination of natural constants in the energy formula is called the Rydberg energy (RE):

This expression is clarified by interpreting it in combinations that form more natural units:

- is the rest mass energy of the electron (511 keV),

- is the fine-structure constant,

- .

Since this derivation is with the assumption that the nucleus is orbited by one electron, we can generalize this result by letting the nucleus have a charge q = Ze, where Z is the atomic number. This will now give us energy levels for hydrogenic (hydrogen-like) atoms, which can serve as a rough order-of-magnitude approximation of the actual energy levels. So for nuclei with Z protons, the energy levels are (to a rough approximation):

The actual energy levels cannot be solved analytically for more than one electron (see n-body problem) because the electrons are not only affected by the nucleus but also interact with each other via the Coulomb force.

When Z = 1/α (Z ≈ 137), the motion becomes highly relativistic, and Z cancels the α in R; the orbit energy begins to be comparable to rest energy. Sufficiently large nuclei, if they were stable, would reduce their charge by creating a bound electron from the vacuum, ejecting the positron to infinity. This is the theoretical phenomenon of electromagnetic charge screening which predicts a maximum nuclear charge. Emission of such positrons has been observed in the collisions of heavy ions to create temporary super-heavy nuclei.

The Bohr formula properly uses the reduced mass of electron and proton in all situations, instead of the mass of the electron,

However, these numbers are very nearly the same, due to the much larger mass of the proton, about 1836.1 times the mass of the electron, so that the reduced mass in the system is the mass of the electron multiplied by the constant 1836.1/(1+1836.1) = 0.99946. This fact was historically important in convincing Rutherford of the importance of Bohr's model, for it explained the fact that the frequencies of lines in the spectra for singly ionized helium do not differ from those of hydrogen by a factor of exactly 4, but rather by 4 times the ratio of the reduced mass for the hydrogen vs. the helium systems, which was much closer to the experimental ratio than exactly 4.

For positronium, the formula uses the reduced mass also, but in this case, it is exactly the electron mass divided by 2. For any value of the radius, the electron and the positron are each moving at half the speed around their common center of mass, and each has only one fourth the kinetic energy. The total kinetic energy is half what it would be for a single electron moving around a heavy nucleus.

- (positronium).

Rydberg formula

Main article: Rydberg formulaBeginning in late 1860s, Johann Balmer and later Johannes Rydberg and Walther Ritz developed increasingly accurate empirical formula matching measured atomic spectral lines. Critical for Bohr's later work, Rydberg expressed his formula in terms of wave-number, equivalent to frequency. These formula contained a constant, , now known the Rydberg constant and a pair of integers indexing the lines: Despite many attempts, no theory of the atom could reproduce these relatively simple formula.

In Bohr's theory describing the energies of transitions or quantum jumps between orbital energy levels is able to explain these formula. For the hydrogen atom Bohr starts with his derived formula for the energy released as a free electron moves into a stable circular orbit indexed by : The energy difference between two such levels is then: Therefore, Bohr's theory gives the Rydberg formula and moreover the numerical value the Rydberg constant for hydrogen in terms of more fundamental constants of nature, including the electron's charge, the electron's mass, and the Planck constant:

Since the energy of a photon is

these results can be expressed in terms of the wavelength of the photon given off:

Bohr's derivation of the Rydberg constant, as well as the concomitant agreement of Bohr's formula with experimentally observed spectral lines of the Lyman (nf =1), Balmer (nf =2), and Paschen (nf =3) series, and successful theoretical prediction of other lines not yet observed, was one reason that his model was immediately accepted.

To apply to atoms with more than one electron, the Rydberg formula can be modified by replacing Z with Z − b or n with n − b where b is constant representing a screening effect due to the inner-shell and other electrons (see Electron shell and the later discussion of the "Shell Model of the Atom" below). This was established empirically before Bohr presented his model.

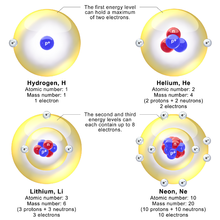

Shell model (heavier atoms)

Main article: Electron shellBohr's original three papers in 1913 described mainly the electron configuration in lighter elements. Bohr called his electron shells, "rings" in 1913. Atomic orbitals within shells did not exist at the time of his planetary model. Bohr explains in Part 3 of his famous 1913 paper that the maximum electrons in a shell is eight, writing: "We see, further, that a ring of n electrons cannot rotate in a single ring round a nucleus of charge ne unless n < 8." For smaller atoms, the electron shells would be filled as follows: "rings of electrons will only join together if they contain equal numbers of electrons; and that accordingly the numbers of electrons on inner rings will only be 2, 4, 8". However, in larger atoms the innermost shell would contain eight electrons, "on the other hand, the periodic system of the elements strongly suggests that already in neon N = 10 an inner ring of eight electrons will occur". Bohr wrote "From the above we are led to the following possible scheme for the arrangement of the electrons in light atoms:"

| Element | Electrons per shell | Element | Electrons per shell | Element | Electrons per shell |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 9 | 4, 4, 1 | 17 | 8, 4, 4, 1 |

| 2 | 2 | 10 | 8, 2 | 18 | 8, 8, 2 |

| 3 | 2, 1 | 11 | 8, 2, 1 | 19 | 8, 8, 2, 1 |

| 4 | 2, 2 | 12 | 8, 2, 2 | 20 | 8, 8, 2, 2 |

| 5 | 2, 3 | 13 | 8, 2, 3 | 21 | 8, 8, 2, 3 |

| 6 | 2, 4 | 14 | 8, 2, 4 | 22 | 8, 8, 2, 4 |

| 7 | 4, 3 | 15 | 8, 4, 3 | 23 | 8, 8, 4, 3 |

| 8 | 4, 2, 2 | 16 | 8, 4, 2, 2 | 24 | 8, 8, 4, 2, 2 |

In Bohr's third 1913 paper Part III called "Systems Containing Several Nuclei", he says that two atoms form molecules on a symmetrical plane and he reverts to describing hydrogen. The 1913 Bohr model did not discuss higher elements in detail and John William Nicholson was one of the first to prove in 1914 that it couldn't work for lithium, but was an attractive theory for hydrogen and ionized helium.

In 1921, following the work of chemists and others involved in work on the periodic table, Bohr extended the model of hydrogen to give an approximate model for heavier atoms. This gave a physical picture that reproduced many known atomic properties for the first time although these properties were proposed contemporarily with the identical work of chemist Charles Rugeley Bury

Bohr's partner in research during 1914 to 1916 was Walther Kossel who corrected Bohr's work to show that electrons interacted through the outer rings, and Kossel called the rings: "shells". Irving Langmuir is credited with the first viable arrangement of electrons in shells with only two in the first shell and going up to eight in the next according to the octet rule of 1904, although Kossel had already predicted a maximum of eight per shell in 1916. Heavier atoms have more protons in the nucleus, and more electrons to cancel the charge. Bohr took from these chemists the idea that each discrete orbit could only hold a certain number of electrons. Per Kossel, after that the orbit is full, the next level would have to be used. This gives the atom a shell structure designed by Kossel, Langmuir, and Bury, in which each shell corresponds to a Bohr orbit.

This model is even more approximate than the model of hydrogen, because it treats the electrons in each shell as non-interacting. But the repulsions of electrons are taken into account somewhat by the phenomenon of screening. The electrons in outer orbits do not only orbit the nucleus, but they also move around the inner electrons, so the effective charge Z that they feel is reduced by the number of the electrons in the inner orbit.

For example, the lithium atom has two electrons in the lowest 1s orbit, and these orbit at Z = 2. Each one sees the nuclear charge of Z = 3 minus the screening effect of the other, which crudely reduces the nuclear charge by 1 unit. This means that the innermost electrons orbit at approximately 1/2 the Bohr radius. The outermost electron in lithium orbits at roughly the Bohr radius, since the two inner electrons reduce the nuclear charge by 2. This outer electron should be at nearly one Bohr radius from the nucleus. Because the electrons strongly repel each other, the effective charge description is very approximate; the effective charge Z doesn't usually come out to be an integer.

The shell model was able to qualitatively explain many of the mysterious properties of atoms which became codified in the late 19th century in the periodic table of the elements. One property was the size of atoms, which could be determined approximately by measuring the viscosity of gases and density of pure crystalline solids. Atoms tend to get smaller toward the right in the periodic table, and become much larger at the next line of the table. Atoms to the right of the table tend to gain electrons, while atoms to the left tend to lose them. Every element on the last column of the table is chemically inert (noble gas).

In the shell model, this phenomenon is explained by shell-filling. Successive atoms become smaller because they are filling orbits of the same size, until the orbit is full, at which point the next atom in the table has a loosely bound outer electron, causing it to expand. The first Bohr orbit is filled when it has two electrons, which explains why helium is inert. The second orbit allows eight electrons, and when it is full the atom is neon, again inert. The third orbital contains eight again, except that in the more correct Sommerfeld treatment (reproduced in modern quantum mechanics) there are extra "d" electrons. The third orbit may hold an extra 10 d electrons, but these positions are not filled until a few more orbitals from the next level are filled (filling the n=3 d orbitals produces the 10 transition elements). The irregular filling pattern is an effect of interactions between electrons, which are not taken into account in either the Bohr or Sommerfeld models and which are difficult to calculate even in the modern treatment.

Moseley's law and calculation (K-alpha X-ray emission lines)

Niels Bohr said in 1962: "You see actually the Rutherford work was not taken seriously. We cannot understand today, but it was not taken seriously at all. There was no mention of it any place. The great change came from Moseley."

In 1913, Henry Moseley found an empirical relationship between the strongest X-ray line emitted by atoms under electron bombardment (then known as the K-alpha line), and their atomic number Z. Moseley's empiric formula was found to be derivable from Rydberg's formula and later Bohr's formula (Moseley actually mentions only Ernest Rutherford and Antonius Van den Broek in terms of models as these had been published before Moseley's work and Moseley's 1913 paper was published the same month as the first Bohr model paper). The two additional assumptions that this X-ray line came from a transition between energy levels with quantum numbers 1 and 2, and , that the atomic number Z when used in the formula for atoms heavier than hydrogen, should be diminished by 1, to (Z − 1).

Moseley wrote to Bohr, puzzled about his results, but Bohr was not able to help. At that time, he thought that the postulated innermost "K" shell of electrons should have at least four electrons, not the two which would have neatly explained the result. So Moseley published his results without a theoretical explanation.

It was Walther Kossel in 1914 and in 1916 who explained that in the periodic table new elements would be created as electrons were added to the outer shell. In Kossel's paper, he writes: "This leads to the conclusion that the electrons, which are added further, should be put into concentric rings or shells, on each of which ... only a certain number of electrons—namely, eight in our case—should be arranged. As soon as one ring or shell is completed, a new one has to be started for the next element; the number of electrons, which are most easily accessible, and lie at the outermost periphery, increases again from element to element and, therefore, in the formation of each new shell the chemical periodicity is repeated." Later, chemist Langmuir realized that the effect was caused by charge screening, with an inner shell containing only 2 electrons. In his 1919 paper, Irving Langmuir postulated the existence of "cells" which could each only contain two electrons each, and these were arranged in "equidistant layers".

In the Moseley experiment, one of the innermost electrons in the atom is knocked out, leaving a vacancy in the lowest Bohr orbit, which contains a single remaining electron. This vacancy is then filled by an electron from the next orbit, which has n=2. But the n=2 electrons see an effective charge of Z − 1, which is the value appropriate for the charge of the nucleus, when a single electron remains in the lowest Bohr orbit to screen the nuclear charge +Z, and lower it by −1 (due to the electron's negative charge screening the nuclear positive charge). The energy gained by an electron dropping from the second shell to the first gives Moseley's law for K-alpha lines,

or

Here, Rv = RE/h is the Rydberg constant, in terms of frequency equal to 3.28 x 10 Hz. For values of Z between 11 and 31 this latter relationship had been empirically derived by Moseley, in a simple (linear) plot of the square root of X-ray frequency against atomic number (however, for silver, Z = 47, the experimentally obtained screening term should be replaced by 0.4). Notwithstanding its restricted validity, Moseley's law not only established the objective meaning of atomic number, but as Bohr noted, it also did more than the Rydberg derivation to establish the validity of the Rutherford/Van den Broek/Bohr nuclear model of the atom, with atomic number (place on the periodic table) standing for whole units of nuclear charge. Van den Broek had published his model in January 1913 showing the periodic table was arranged according to charge while Bohr's atomic model was not published until July 1913.

The K-alpha line of Moseley's time is now known to be a pair of close lines, written as (Kα1 and Kα2) in Siegbahn notation.

Shortcomings

The Bohr model gives an incorrect value L=ħ for the ground state orbital angular momentum: The angular momentum in the true ground state is known to be zero from experiment. Although mental pictures fail somewhat at these levels of scale, an electron in the lowest modern "orbital" with no orbital momentum, may be thought of as not to revolve "around" the nucleus at all, but merely to go tightly around it in an ellipse with zero area (this may be pictured as "back and forth", without striking or interacting with the nucleus). This is only reproduced in a more sophisticated semiclassical treatment like Sommerfeld's. Still, even the most sophisticated semiclassical model fails to explain the fact that the lowest energy state is spherically symmetric – it doesn't point in any particular direction.

Nevertheless, in the modern fully quantum treatment in phase space, the proper deformation (careful full extension) of the semi-classical result adjusts the angular momentum value to the correct effective one. As a consequence, the physical ground state expression is obtained through a shift of the vanishing quantum angular momentum expression, which corresponds to spherical symmetry.

In modern quantum mechanics, the electron in hydrogen is a spherical cloud of probability that grows denser near the nucleus. The rate-constant of probability-decay in hydrogen is equal to the inverse of the Bohr radius, but since Bohr worked with circular orbits, not zero area ellipses, the fact that these two numbers exactly agree is considered a "coincidence". (However, many such coincidental agreements are found between the semiclassical vs. full quantum mechanical treatment of the atom; these include identical energy levels in the hydrogen atom and the derivation of a fine-structure constant, which arises from the relativistic Bohr–Sommerfeld model (see below) and which happens to be equal to an entirely different concept, in full modern quantum mechanics).

The Bohr model also has difficulty with, or else fails to explain:

- Much of the spectra of larger atoms. At best, it can make predictions about the K-alpha and some L-alpha X-ray emission spectra for larger atoms, if two additional ad hoc assumptions are made. Emission spectra for atoms with a single outer-shell electron (atoms in the lithium group) can also be approximately predicted. Also, if the empiric electron–nuclear screening factors for many atoms are known, many other spectral lines can be deduced from the information, in similar atoms of differing elements, via the Ritz–Rydberg combination principles (see Rydberg formula). All these techniques essentially make use of Bohr's Newtonian energy-potential picture of the atom.

- The relative intensities of spectral lines; although in some simple cases, Bohr's formula or modifications of it, was able to provide reasonable estimates (for example, calculations by Kramers for the Stark effect).

- The existence of fine structure and hyperfine structure in spectral lines, which are known to be due to a variety of relativistic and subtle effects, as well as complications from electron spin.

- The Zeeman effect – changes in spectral lines due to external magnetic fields; these are also due to more complicated quantum principles interacting with electron spin and orbital magnetic fields.

- The model also violates the uncertainty principle in that it considers electrons to have known orbits and locations, two things which cannot be measured simultaneously.

- Doublets and triplets appear in the spectra of some atoms as very close pairs of lines. Bohr's model cannot say why some energy levels should be very close together.

- Multi-electron atoms do not have energy levels predicted by the model. It does not work for (neutral) helium.

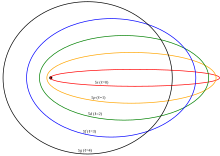

Refinements

Several enhancements to the Bohr model were proposed, most notably the Sommerfeld or Bohr–Sommerfeld models, which suggested that electrons travel in elliptical orbits around a nucleus instead of the Bohr model's circular orbits. This model supplemented the quantized angular momentum condition of the Bohr model with an additional radial quantization condition, the Wilson–Sommerfeld quantization condition

where pr is the radial momentum canonically conjugate to the coordinate qr, which is the radial position, and T is one full orbital period. The integral is the action of action-angle coordinates. This condition, suggested by the correspondence principle, is the only one possible, since the quantum numbers are adiabatic invariants.

The Bohr–Sommerfeld model was fundamentally inconsistent and led to many paradoxes. The magnetic quantum number measured the tilt of the orbital plane relative to the xy plane, and it could only take a few discrete values. This contradicted the obvious fact that an atom could have any orientation relative to the coordinates, without restriction. The Sommerfeld quantization can be performed in different canonical coordinates and sometimes gives different answers. The incorporation of radiation corrections was difficult, because it required finding action-angle coordinates for a combined radiation/atom system, which is difficult when the radiation is allowed to escape. The whole theory did not extend to non-integrable motions, which meant that many systems could not be treated even in principle. In the end, the model was replaced by the modern quantum-mechanical treatment of the hydrogen atom, which was first given by Wolfgang Pauli in 1925, using Heisenberg's matrix mechanics. The current picture of the hydrogen atom is based on the atomic orbitals of wave mechanics, which Erwin Schrödinger developed in 1926.

However, this is not to say that the Bohr–Sommerfeld model was without its successes. Calculations based on the Bohr–Sommerfeld model were able to accurately explain a number of more complex atomic spectral effects. For example, up to first-order perturbations, the Bohr model and quantum mechanics make the same predictions for the spectral line splitting in the Stark effect. At higher-order perturbations, however, the Bohr model and quantum mechanics differ, and measurements of the Stark effect under high field strengths helped confirm the correctness of quantum mechanics over the Bohr model. The prevailing theory behind this difference lies in the shapes of the orbitals of the electrons, which vary according to the energy state of the electron.

The Bohr–Sommerfeld quantization conditions lead to questions in modern mathematics. Consistent semiclassical quantization condition requires a certain type of structure on the phase space, which places topological limitations on the types of symplectic manifolds which can be quantized. In particular, the symplectic form should be the curvature form of a connection of a Hermitian line bundle, which is called a prequantization.

Bohr also updated his model in 1922, assuming that certain numbers of electrons (for example, 2, 8, and 18) correspond to stable "closed shells".

Model of the chemical bond

Main article: Bohr model of the chemical bondNiels Bohr proposed a model of the atom and a model of the chemical bond. According to his model for a diatomic molecule, the electrons of the atoms of the molecule form a rotating ring whose plane is perpendicular to the axis of the molecule and equidistant from the atomic nuclei. The dynamic equilibrium of the molecular system is achieved through the balance of forces between the forces of attraction of nuclei to the plane of the ring of electrons and the forces of mutual repulsion of the nuclei. The Bohr model of the chemical bond took into account the Coulomb repulsion – the electrons in the ring are at the maximum distance from each other.

Symbolism of planetary atomic models

Although Bohr's atomic model was superseded by quantum models in the 1920s, the visual image of electrons orbiting a nucleus has remained the popular concept of atoms. The concept of an atom as a tiny planetary system has been widely used as a symbol for atoms and even for "atomic" energy (even though this is more properly considered nuclear energy). Examples of its use over the past century include but are not limited to:

- The logo of the United States Atomic Energy Commission, which was in part responsible for its later usage in relation to nuclear fission technology in particular.

- The flag of the International Atomic Energy Agency is a "crest-and-spinning-atom emblem", enclosed in olive branches.

- The US minor league baseball Albuquerque Isotopes' logo shows baseballs as electrons orbiting a large letter "A".

- A similar symbol, the atomic whirl, was chosen as the symbol for the American Atheists, and has come to be used as a symbol of atheism in general.

- The Unicode Miscellaneous Symbols code point U+269B (⚛) for an atom looks like a planetary atom model.

- The television show The Big Bang Theory uses a planetary-like image in its print logo.

- The JavaScript library React uses planetary-like image as its logo.

- On maps, it is generally used to indicate a nuclear power installation.

See also

- 1913 in science

- Balmer's Constant

- Bohr–Sommerfeld model

- The Franck–Hertz experiment provided early support for the Bohr model.

- The inert-pair effect is adequately explained by means of the Bohr model.

- Introduction to quantum mechanics

References

Footnotes

- ^ Lakhtakia, Akhlesh; Salpeter, Edwin E. (1996). "Models and Modelers of Hydrogen". American Journal of Physics. 65 (9): 933. Bibcode:1997AmJPh..65..933L. doi:10.1119/1.18691.

- Perrin, Jean (1901). "Les Hypothèses moléculaires". La Revue scientifique: 463.

- de Broglie et al. 1912, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Kragh, Helge (1 January 1979). "Niels Bohr's Second Atomic Theory". Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences. 10: 123–186. doi:10.2307/27757389. JSTOR 27757389.

- ^ Kragh, Helge (2012). Niels Bohr and the Quantum Atom: The Bohr Model of Atomic Structure 1913–1925. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-163046-0.

- Helge Kragh (Oct. 2010). Before Bohr: Theories of atomic structure 1850-1913. RePoSS: Research Publications on Science Studies 10. Aarhus: Centre for Science Studies, University of Aarhus.

- Wheaton, Bruce R. (1992). The tiger and the shark: empirical roots of wave-particle dualism (1. paperback ed., reprinted ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-35892-7.

- ^ Heilbron, John L.; Kuhn, Thomas S. (1969). "The Genesis of the Bohr Atom". Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences. 1: vi–290. doi:10.2307/27757291. JSTOR 27757291.

- ^ John L, Heilbron (1985). "Bohr's First Theories of the Atom". In French, A. P.; Kennedy, P. J. (eds.). Niels Bohr: a centenary volume. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-62415-3.

- Heilbron, John L. (1968). "The Scattering of α and β Particles and Rutherford's Atom". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 4 (4): 247–307. doi:10.1007/BF00411591. ISSN 0003-9519. JSTOR 41133273.

- ^ Bohr, N. (July 1913). "I. On the constitution of atoms and molecules". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 26 (151): 1–25. Bibcode:1913PMag...26....1B. doi:10.1080/14786441308634955.

- Rayleigh, Lord (January 1906). "VII. On electrical vibrations and the constitution of the atom". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 11 (61): 117–123. doi:10.1080/14786440609463428.

- Whittaker, Edmund T. (1989). A history of the theories of aether & electricity. 2: The modern theories, 1900 - 1926 (Repr ed.). New York: Dover Publ. ISBN 978-0-486-26126-3.

- ^ Pais, Abraham (2002). Inward bound: of matter and forces in the physical world (Reprint ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press ISBN 978-0-19-851997-3.

- Bohr, N. (December 1925). "Atomic Theory and Mechanics1". Nature. 116 (2927): 845–852. doi:10.1038/116845a0. ISSN 0028-0836.

- Perović, Slobodan (2021). "Spectral Lines, Quantum States, and a Master Model of the Atom". From data to quanta: Niels Bohr's vision of physics. Chicago London: The University of Chicago press. ISBN 978-0-226-79833-2.

- ^ Giliberti, Marco; Lovisetti, Luisa (2024). "Bohr's Hydrogen Atom". Old Quantum Theory and Early Quantum Mechanics. Challenges in Physics Education. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-57934-9_6. ISBN 978-3-031-57933-2.

- ^ Bohr, Niels (7 November 1962). "Niels Bohr – Session III" (Interview). Interviewed by Thomas S. Kuhn; Leon Rosenfeld; Aage Petersen; Erik Rudinger. American Institute of Physics.

- ^ Heilbron, John L. (June 2013). "The path to the quantum atom". Nature. 498 (7452): 27–30. doi:10.1038/498027a. PMID 23739408. S2CID 4355108.

- ^ McCormmach, Russell (1 January 1966). "The atomic theory of John William Nicholson". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 3 (2): 160–184. doi:10.1007/BF00357268. JSTOR 41133258. S2CID 120797894.

- ^ Nicholson, J. W. (14 June 1912). "The Constitution of the Solar Corona. IL". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 72 (8). Oxford University Press: 677–693. doi:10.1093/mnras/72.8.677. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ Bohr, Niels; Rosenfeld, Léon Jacques Henri Constant (1963). On the Constitution of Atoms and Molecules ... Papers of 1913 reprinted from the Philosophical Magazine, with an introduction by L. Rosenfeld. Copenhagen; W.A. Benjamin: New York. OCLC 557599205.

- Stachel, John (2009). "Bohr and the Photon". Quantum Reality, Relativistic Causality, and Closing the Epistemic Circle. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 79.

- Gilder, Louisa (2009). "The Arguments 1909—1935". The Age of Entanglement. p. 55.

Well, yes," says Bohr. "But I can hardly imagine it will involve light quanta. Look, even if Einstein had found an unassailable proof of their existence and would want to inform me by telegram, this telegram would only reach me because of the existence and reality of radio waves.

- "Revealing the hidden connection between pi and Bohr's hydrogen model". Physics World. November 17, 2015.

- Müller, U.; de Reus, T.; Reinhardt, J.; Müller, B.; Greiner, W. (1988-03-01). "Positron production in crossed beams of bare uranium nuclei". Physical Review A. 37 (5): 1449–1455. Bibcode:1988PhRvA..37.1449M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.37.1449. PMID 9899816. S2CID 35364965.

- Bohr, N. (1985). "Rydberg's discovery of the spectral laws". In Kalckar, J. (ed.). Collected works. Vol. 10. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publ. Cy. pp. 373–379.

- Bohr, N. (July 1913). "I. On the constitution of atoms and molecules". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 26 (151): 1–25. doi:10.1080/14786441308634955. ISSN 1941-5982.

- Baggott, J. E. (2013). The quantum story: a history in 40 moments (Impression: 3 ed.). Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-19-965597-7.

- ^ Baily, C. (2013-01-01). "Early atomic models – from mechanical to quantum (1904–1913)". The European Physical Journal H. 38 (1): 1–38. doi:10.1140/epjh/e2012-30009-7. ISSN 2102-6467.

- Bohr, N. (1913). "On the Constitution of Atoms and Molecules, Part II. Systems containing only a Single Nucleus". Philosophical Magazine. 26: 476–502.

- Bohr, N. (1 November 1913). "LXXIII. On the constitution of atoms and molecules". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 26 (155): 857–875. Bibcode:1913PMag...26..857B. doi:10.1080/14786441308635031.

- Nicholson, J. W. (May 1914). "The Constitution of Atoms and Molecules". Nature. 93 (2324): 268–269. Bibcode:1914Natur..93..268N. doi:10.1038/093268a0. S2CID 3977652.

- Bury, Charles R. (July 1921). "Langmuir's Theory of the Arrangement of Electrons in Atoms and Molecules". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 43 (7): 1602–1609. doi:10.1021/ja01440a023.

- ^ Kossel, W. (1916). "Über Molekülbildung als Frage des Atombaus" [On molecular formation as a question of atomic structure]. Annalen der Physik (in German). 354 (3): 229–362. Bibcode:1916AnP...354..229K. doi:10.1002/andp.19163540302.

- ^ Kragh, Helge (2012). "Lars Vegard, atomic structure, and the periodic system" (PDF). Bulletin for the History of Chemistry. 37 (1): 42–49. OCLC 797965772. S2CID 53520045. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- Langmuir, Irving (June 1919). "The Arrangement of Electrons in Atoms and Molecules". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 41 (6): 868–934. doi:10.1021/ja02227a002.

- Bohr, Niels (31 October 1962). "Niels Bohr – Session I" (Interview). Interviewed by Thomas S. Kuhn; Leon Rosenfeld; Aage Petersen; Erik Rudinger. American Institute of Physics.

- Moseley, H.G.J. (1913). "The high-frequency spectra of the elements". Philosophical Magazine. 6th series. 26: 1024–1034.

- M.A.B. Whitaker (1999). "The Bohr–Moseley synthesis and a simple model for atomic x-ray energies". European Journal of Physics. 20 (3): 213–220. Bibcode:1999EJPh...20..213W. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/20/3/312. S2CID 250901403.

- van den Broek, Antonius (January 1913). "Die Radioelemente, das periodische System und die Konstitution der. Atome". Physikalische Zeitschrift (in German). 14: 32–41.

- Dahl, Jens Peder; Springborg, Michael (10 December 1982). "Wigner's phase space function and atomic structure: I. The hydrogen atom ground state". Molecular Physics. 47 (5): 1001–1019. doi:10.1080/00268978200100752. S2CID 9628509.

- A. Sommerfeld (1916). "Zur Quantentheorie der Spektrallinien". Annalen der Physik (in German). 51 (17): 1–94. Bibcode:1916AnP...356....1S. doi:10.1002/andp.19163561702.

- W. Wilson (1915). "The quantum theory of radiation and line spectra". Philosophical Magazine. 29 (174): 795–802. doi:10.1080/14786440608635362.

- Shaviv, Glora (2010). The Life of Stars: The Controversial Inception and Emergence of the Theory of Stellar Structure. Springer. p. 203. ISBN 978-3642020872.

- Бор Н. (1970). Избранные научные труды (статьи 1909–1925). Vol. 1. М.: «Наука». p. 133.

- Svidzinsky, Anatoly A.; Scully, Marlan O.; Herschbach, Dudley R. (23 August 2005). "Bohr's 1913 molecular model revisited". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (34): 11985–11988. arXiv:physics/0508161. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10211985S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505778102. PMC 1186029. PMID 16103360.

- Schirrmacher, Arne (2009). "Bohr's Atomic Model". In Greenberger, Daniel M.; Hentschel, Klaus; Weinert, Friedel (eds.). Compendium of quantum physics: concepts, experiments, history, and philosophy. Heidelberg New York: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-70626-7.

- "Logo Usage Guidelines". www.iaea.org. 2021-11-23. Retrieved 2024-09-04.

Primary sources

- Bohr, N. (July 1913). "I. On the constitution of atoms and molecules". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 26 (151): 1–25. Bibcode:1913PMag...26....1B. doi:10.1080/14786441308634955.

- Bohr, N. (September 1913). "XXXVII. On the constitution of atoms and molecules". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 26 (153): 476–502. Bibcode:1913PMag...26..476B. doi:10.1080/14786441308634993.

- Bohr, N. (1 November 1913). "LXXIII. On the constitution of atoms and molecules". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 26 (155): 857–875. Bibcode:1913PMag...26..857B. doi:10.1080/14786441308635031.

- Bohr, N. (October 1913). "The Spectra of Helium and Hydrogen". Nature. 92 (2295): 231–232. Bibcode:1913Natur..92..231B. doi:10.1038/092231d0. S2CID 11988018.

- Bohr, N. (March 1921). "Atomic Structure". Nature. 107 (2682): 104–107. Bibcode:1921Natur.107..104B. doi:10.1038/107104a0. S2CID 4035652.

- A. Einstein (1917). "Zum Quantensatz von Sommerfeld und Epstein". Verhandlungen der Deutschen Physikalischen Gesellschaft. 19: 82–92. Reprinted in The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, A. Engel translator, (1997) Princeton University Press, Princeton. 6 p. 434. (provides an elegant reformulation of the Bohr–Sommerfeld quantization conditions, as well as an important insight into the quantization of non-integrable (chaotic) dynamical systems.)

- de Broglie, Maurice; Langevin, Paul; Solvay, Ernest; Einstein, Albert (1912). La théorie du rayonnement et les quanta : rapports et discussions de la réunion tenue à Bruxelles, du 30 octobre au 3 novembre 1911, sous les auspices de M.E. Solvay (in French). Gauthier-Villars. OCLC 1048217622.

Further reading

- Linus Carl Pauling (1970). "Chapter 5-1". General Chemistry (3rd ed.). San Francisco: W.H. Freeman & Co.

- Reprint: Linus Pauling (1988). General Chemistry. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-65622-5.

- George Gamow (1985). "Chapter 2". Thirty Years That Shook Physics. Dover Publications.

- Walter J. Lehmann (1972). "Chapter 18". Atomic and Molecular Structure: the development of our concepts. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-52440-9.

- Paul Tipler and Ralph Llewellyn (2002). Modern Physics (4th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-4345-0.

- Klaus Hentschel: Elektronenbahnen, Quantensprünge und Spektren, in: Charlotte Bigg & Jochen Hennig (eds.) Atombilder. Ikonografien des Atoms in Wissenschaft und Öffentlichkeit des 20. Jahrhunderts, Göttingen: Wallstein-Verlag 2009, pp. 51–61

- Steven and Susan Zumdahl (2010). "Chapter 7.4". Chemistry (8th ed.). Brooks/Cole. ISBN 978-0-495-82992-8.

- Kragh, Helge (November 2011). "Conceptual objections to the Bohr atomic theory — do electrons have a 'free will'?". The European Physical Journal H. 36 (3): 327–352. Bibcode:2011EPJH...36..327K. doi:10.1140/epjh/e2011-20031-x. S2CID 120859582.

External links

- Standing waves in Bohr's atomic model—An interactive simulation to intuitively explain the quantization condition of standing waves in Bohr's atomic mode

| Atomic models | |

|---|---|

| Historic models |

|

| Current models |

|

, on a sphere of radius a to equal the frequency, f, of the electron's orbit on the sphere times the

, on a sphere of radius a to equal the frequency, f, of the electron's orbit on the sphere times the  where e represents the charge on the electron and the sphere. Haas combined this constraint with the balance-of-forces equation. The attractive force between the electron and the sphere balances the

where e represents the charge on the electron and the sphere. Haas combined this constraint with the balance-of-forces equation. The attractive force between the electron and the sphere balances the  where m is the mass of the electron. This combination relates the radius of the sphere to the Planck constant:

where m is the mass of the electron. This combination relates the radius of the sphere to the Planck constant:

Haas solved for the Planck constant using the then-current value for the radius of the hydrogen atom.

Three years later, Bohr would use similar equations with different interpretation. Bohr took the Planck constant as given value and used the equations to predict, a, the radius of the electron orbiting in the ground state of the hydrogen atom. This value is now called the

Haas solved for the Planck constant using the then-current value for the radius of the hydrogen atom.

Three years later, Bohr would use similar equations with different interpretation. Bohr took the Planck constant as given value and used the equations to predict, a, the radius of the electron orbiting in the ground state of the hydrogen atom. This value is now called the  , where

, where  is called the

is called the  . The lowest value of

. The lowest value of  is 1; this gives the smallest possible orbital radius, known as the

is 1; this gives the smallest possible orbital radius, known as the  determined by the energy difference of the levels according to the

determined by the energy difference of the levels according to the  , where

, where  is the Planck constant.

is the Planck constant. and

and  when

when  is much smaller than

is much smaller than  , was later reinterpreted in 1924 by

, was later reinterpreted in 1924 by

is the angular momentum of the orbiting electron. Writing

is the angular momentum of the orbiting electron. Writing  for this angular momentum, the previous equation becomes

for this angular momentum, the previous equation becomes

while

while  described

described

(where T is the average kinetic energy and U the average electrostatic potential), and that for Kepler's second law, the average separation between the electron and the nucleus is a.

(where T is the average kinetic energy and U the average electrostatic potential), and that for Kepler's second law, the average separation between the electron and the nucleus is a.

is an integer multiple of the energy of a quantum of light with half the frequency of the electron's revolution frequency, i.e.:

is an integer multiple of the energy of a quantum of light with half the frequency of the electron's revolution frequency, i.e.:

, and, denoting the angular momentum of the electron as L, introduces the equation:

, and, denoting the angular momentum of the electron as L, introduces the equation:

is the

is the  is the

is the  .

.

(positronium).

(positronium). , now known the

, now known the  Despite many attempts, no theory of the atom could reproduce these relatively simple formula.

Despite many attempts, no theory of the atom could reproduce these relatively simple formula.

:

:

The energy difference between two such levels is then:

The energy difference between two such levels is then:

Therefore, Bohr's theory gives the Rydberg formula and moreover the numerical value the Rydberg constant for hydrogen in terms of more fundamental constants of nature, including the electron's charge, the electron's mass, and the

Therefore, Bohr's theory gives the Rydberg formula and moreover the numerical value the Rydberg constant for hydrogen in terms of more fundamental constants of nature, including the electron's charge, the electron's mass, and the