The Brakemen's Brotherhood was an early American railroad brotherhood established in 1873. The group was a secret society organizing railroad brakemen into a fraternal benefit society and trade union. The organization was largely destroyed in the aftermath of the failed Great Railroad Strike of 1877, although it continued to maintain an existence nationwide through the 1880s.

Establishment

Although there are some reports of an earlier union of railroad brakemen from the summer of 1869, the Brakemen's Brotherhood is the earliest documented railway brotherhood organizing railroad brakemen.

The Brakemen's Brotherhood was formally established in Hornellsville, New York, in 1873 by local brakemen who worked for the Erie Railroad. The society was apparently patterned after the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers, established in 1869, and was intended as a secret fraternal benefit society, holding weekly meetings in its own meeting hall to conduct organizational business. The Hornellsville local was emulated by brakemen in Port Jervis, New York, and elsewhere and in January 1875 a so-called "First Annual Convention" was held in Hornellsville, with delegates from three lodges in attendance.

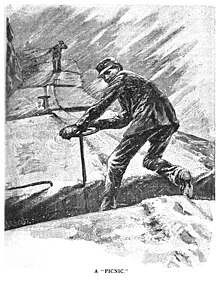

Frequently plying their craft on top of the boxcars of moving trains, railroad brakemen performed statistically what was the most dangerous job in America, the most dangerous single occupation in an industry with an annual death rate estimated at 8 workers per 1000, more than double that of coal mining and hard rock mineral mining. Historian of 19th-century American railroad labor Walter Licht describes their task:

"When the engineer blew the whistle for 'down brakes,' brake crews scurried to their posts on top of the cars to turn the brake wheels. Normally assigned to two or three cars, the brakers often found themselves manning five or six as companies sought to reduce their operating staffs. While running from car to car, it was easy to slip and fall, or to be hit by overhead obstructions. The work was particularly dangerous at night or during storms."

In the early era of railroad transportation, brakemen also performed similar dangerous tasks as railroad switchmen, coupling and uncoupling cars by standing behind a moving train a dropping a heavy pin through the top of a drawhead to link cars, a process that all too frequently resulted in mutilated hands or lost limbs. The brotherhood provided a sort of death and disability benefit to the families of its members, paying out several hundred thousand dollars in benefits by the end of the 1880s.

In light of the dangerous and comparatively poorly-paid occupation, brakemen were among the most militant workers of the 19th century American railroad industry, taking an active part in all major work stoppages of the 1870s. Strikes were then particularly frequent in Hornellsville, indicating the likelihood that the Brakemen's Brotherhood served a coordinating function in strike actions throughout its existence.

Development

Brakemen worked in a sort of master and apprentice relationship under the supervision of railroad conductors. It is not surprising then that the chief organizer and first President of the Brakemen's Brotherhood was himself a conductor, W.L. Collins. As part of his organizing mission, Collins hit the road in the fall of 1875, traveling throughout the Western and Southern United States in an effort to organize lodges of the Brakemen's Brotherhood.

Despite the name of the organization, membership was not exclusively limited to brakemen but rather was more akin in nature to that of an industrial union, including among its ranks locomotive engineers, as well as thousands of trackmen and shop workers. The organization seems to have been strongest in the Midwest, with a presence on virtually every railroad in Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. Its extreme secrecy makes total membership numbers of the Brakemen's Brotherhood unknown, but observers believed the organization had an extensive presence, with the Hornellsville Lodge No. 1 alone including approximately 150 members.

The Erie Railroad brakemen and the Brakemen's Brotherhood were part of a strike in 1874 that successfully stopped the reduction of brakemen crews from four to three. They struck again in 1877, ostensibly over the issue of the introduction of "double headers" (two engines pulling a single longer train), which reduced operating costs for the railways by reducing the number of conductors and brakemen needed over that required by two trains of comparable length.

Final years

The Brakemen's Brotherhood was devastated by the aftermath of the failed Great Railroad Strike of 1877, which resulted in a broad swath of terminations of striking workers and their replacement by non-union strikebreakers. While most lodges of the Brakemen's Brotherhood vanished in the aftermath of the 1877 strikes, the organization nevertheless continued to maintain a furtive existence in the Hornellsville area, with city directories maintaining listings for the organization in its 1883 and 1887 editions.

The brotherhood's influence continued as well through the 1880s, holding conventions, forming new chapters and having a presence in the Burlington railroad strike of 1888.

Legacy

The Brakemen's Brotherhood was supplanted with the establishment of a new railway fraternal order, the Brotherhood of Railroad Brakemen, established in Oneonta, New York, in the summer of 1883.

References

- ^ Stromquist 1987, p. 51.

- Licht 1983, p. 182.

- Licht 1983, pp. 182–183.

- Licht 1983, p. 183.

- ^ "The Brakemen's Brotherhood". Mansfield Advertiser. Mansfield, PA. November 10, 1886. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Laid At Rest". The Nebraska State Journal. Lincoln, NE. March 12, 1890. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Brakemen's Brotherhood". The Republic. Columbus, IN. October 26, 1888. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Funeral Of A Brother". Quad-City Times. Davenport, IA. January 26, 1886. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Work of the Brakemen's Brotherhood". The Junction City Tribune. Junction City, KS. October 25, 1888. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

...there have been 304 deaths and 157 disability claims paid, amounting in all to about $300,000.

- ^ Stromquist 1987, p. 52.

- ^ Stromquist 2008, p. 61.

- ^ Stromquist 2008, p. 59.

- "Brakemen's Brotherhood". The Pantograph. Bloomington, IL. February 9, 1885. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Strike Situation". Fort Scott Weekly Monitor. Fort Scott, KS. March 15, 1888. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Brakemen Ready To Strike". St. Joseph Gazette-Herald. St. Joseph, MO. March 11, 1888. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com.

- McCaleb 1936, p. 1.

- Licht, Walter (1983). Working for the Railroad: The Organization of Work in the Nineteenth Century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- McCaleb, Walter F. (1936). Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen: With Special Reference to the Life of Alexander F. Whitney. New York: Albert and Charles Boni.

- Stromquist, Shelton (1987). A Generation of Boomers: The Pattern of Railroad Labor Conflict in Nineteenth-Century America. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Stromquist, Shelton (2008). "'Our Rights as Workingmen': Class Traditions and Collective Action in a Nineteenth-Century Railroad Town, Hornellsville, New York, 1869-82". In Stowell, David O. (ed.). The Great Strikes of 1877. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Further reading

- Taillon, Paul Michel (2009). Good, Reliable, White Men: Railroad Brotherhoods, 1877-1917. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.