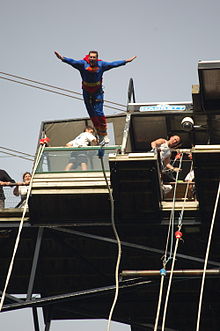

Bungee jumping (/ˈbʌndʒi/), also spelled bungy jumping, is an activity that involves a person jumping from a great height while connected to a large elastic cord. The launching pad is usually erected on a tall structure such as a building or crane, a bridge across a deep ravine, or on a natural geographic feature such as a cliff. It is also possible to jump from a type of aircraft that has the ability to hover above the ground, such as a hot-air-balloon or helicopter. The thrill comes from the free-falling and the rebound. When the person jumps, the cord stretches and the jumper flies upwards again as the cord recoils, and continues to oscillate up and down until all the kinetic energy is dissipated.

Etymology

The word "bungee" originates from West Country dialect of the English language, meaning "anything thick and squat", as defined by James Jennings in his book "Observations of Some of the Dialects in The West of England" published 1825. In 1928, the word started to be used for a rubber eraser.

The Oxford English Dictionary records early use of the phrase in 1938 relating to launching of gliders using an elasticated cord, and also as "a long nylon-cased rubber band used for securing luggage".

History

Early tethered jumping

The land diving (Sa: Gol) of Pentecost Island in Vanuatu is an ancient ritual in which young men jump from tall wooden platforms with vines tied to their ankles as a test of their courage and passage into manhood. Unlike in modern bungee-jumping, land-divers intentionally hit the ground, but the vines absorb sufficient force to make the impact non-lethal. The land-diving ritual on Pentecost has been claimed as an inspiration by A. J. Hackett, prompting calls from the islanders' representatives for compensation for what they view as the unauthorised appropriation of their cultural property.

A tower 1,200 metres (4,000 ft) high with a system to drop a "car" suspended by a cable of "best rubber" was proposed for the Chicago World Fair, 1892–1893. The car, seating two hundred people, would have been shoved from a platform on the tower and then would have bounced to a stop. The designer engineer suggested that for safety the ground below "be covered with eight feet of feather bedding". The proposal was declined by the Fair's organizers.

Braked rope sliding

In 1963, Jim Tyson, a Sydney, Australia commando, slid down a catenary rope, from a cliff, across a Sydney-area river, braking with carpet, releasing mid-river, and swimming to an accessible river bank.

Modern sport

The first modern bungee jumps were made on 1 April 1979 from the 76-metre (250 ft) Clifton Suspension Bridge in Bristol, England, by David Kirke and Simon Keeling, members of the Oxford University Dangerous Sports Club, and Geoff Tabin, a professional climber who tied the ropes for the jump. The students had come up with the idea after discussing the "vine jumping" ritual of Vanuatu. The jumpers were arrested shortly after, but continued with jumps in the US from the Golden Gate Bridge and the Royal Gorge Bridge. The last jump was sponsored by and televised on the American programme That's Incredible, spreading the concept worldwide. By 1982, Kirk and Keelling were jumping from mobile cranes and hot air balloons.

Colorado climbers Mike Munger and Charlie Fowler may have bungee-jumped earlier in Eldorado Springs, CO in 1977. Both were cutting-edge alpinists, preparing for a trip to Monte Fitzroy in Patagonia by simulating long falls onto a springy, 46-metre (150 ft) nylon climbing rope. They scrambled up to a large tree at the top of the 210 m (700 ft) wall, above a severely overhanging climb appropriately named "Diving Board", and tied one end of the rope into the tree. With a piece of flat seat belt webbing around his waist and some homemade leg loops, Mike tied into the other end of the rope and, after no small amount of trepidation, he jumped. He then ascended the rope mechanically to the tree and untied, and then tied in and jumped. The total fall was about 40 m (130 ft).

Organised commercial bungee jumping began with the New Zealander, A. J. Hackett, who made his first jump from Auckland's Greenhithe Bridge in 1986. During the following years, Hackett performed a number of jumps from bridges and other structures (including the Eiffel Tower), building public interest in the sport, and opening the world's first permanent commercial bungee site, the Kawarau Bridge Bungy at the Kawarau Gorge Suspension Bridge near Queenstown in the South Island of New Zealand. Hackett remains one of the largest commercial operators, with concerns in several countries.

Several million successful jumps have taken place since 1980. This safety record is attributable to bungee operators rigorously conforming to standards and guidelines governing jumps, such as double checking calculations and fittings for every jump. As with any sport, injuries can still occur (see below), and there have been fatalities. A relatively common mistake in fatality cases is to use a cord that is too long. The cord should be substantially shorter than the height of the jumping platform to allow it room to stretch. When the cord becomes taut and then is stretched, the tension in the cord progressively increases, building up its potential energy. Initially the tension is less than the jumper's weight and the jumper continues to accelerate downwards. At some point, the tension equals the jumper's weight and the acceleration is temporarily zero. With further stretching, the jumper has an increasing upward acceleration and at some point has zero vertical velocity before recoiling upward.

The Bloukrans River Bridge was the first bridge to be used as a bungee jump launch spot in Africa when Face Adrenalin introduced bungee jumping to the African continent in 1990. Bloukrans Bridge Bungy has been operated commercially by Face Adrenalin since 1997, and is the highest commercial bridge bungy in the world.

In 2008, Carl Dionisio of Durban performed a 30 meter bungy jump attached to a cord made of 18,500 condoms. He currently runs the only Ocean Touch bungy jump in the World at Calheta Beach in Madeira, Portugal, and claims to be the only person operating in the bungy industry single-handed. He holds the world record for being the only person to bungy jump while driving a tower crane at the same time, something that he has done hundreds of times since 2017.

Equipment

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The elastic rope first used in bungee jumping, and still used by many commercial operators, is factory-produced braided shock cord. This special bungee cord consists of many latex strands enclosed in a tough outer cover. The outer cover may be applied when the latex is pre-stressed, so that the cord's resistance to extension is already significant at the cord's natural length. This gives a harder, sharper bounce. The braided cover also provides significant durability benefits. Other operators, including A. J. Hackett and most southern-hemisphere operators, use unbraided cords with exposed latex strands. These give a softer, longer bounce and can be home-produced.

Accidents where participants became detached led many commercial operators to use a body harness, if only as a backup for an ankle attachment. Body harnesses generally derive from climbing equipment rather than parachute equipment.

The highest jump

Milad tower bungee jumping with a height of 280 meters is the highest jumping platform in the world

In August 2005, AJ Hackett added a SkyJump to the Macau Tower, making it the world's highest jump at 233 metres (764 ft). The SkyJump did not qualify as the world's highest bungee as it is not strictly speaking a bungee jump, but instead what is referred to as a 'Decelerator-Descent' jump, using a steel cable and decelerator system, rather than an elastic rope. On 17 December 2006, the Macau Tower started operating a proper bungee jump, which became the "Highest Commercial Bungee Jump in the World" according to the Guinness Book of Records. The Macau Tower Bungy has a "Guide cable" system that limits swing (the jump is very close to the structure of the tower itself) but does not have any effect on the speed of descent, so this still qualifies the jump for the World Record.

Kushma Bungee Jump is the world's second-highest bungee jump with a height of 228 metres (748 ft). It is located in the gorge of Kaligandaki River and world-first natural canyon bungee jump. Another commercial bungee jump currently in operation is just 13 metres (43 ft) smaller, at 220 metres (720 ft). This jump, made without guide ropes, is from the top of the Verzasca Dam near Locarno, Switzerland. It appears in the opening scene of the James Bond film GoldenEye. The 216-metre (709 ft) Bloukrans Bridge Bungy in South Africa and the Verzasca Dam jumps are pure freefall swinging bungee from a single cord.

Guinness only records jumps from fixed objects to guarantee the accuracy of the measurement. John Kockleman however recorded a 670-metre (2,200 ft) bungee jump from a hot air balloon in California in 1989. In 1991 Andrew Salisbury jumped from 2,700 metres (9,000 ft) from a helicopter over Cancun for a television program and with Reebok sponsorship. The full stretch was recorded at 962 metres (3,157 ft). He landed safely under parachute.

One commercial jump higher than all others is at the Royal Gorge Bridge in Colorado. The height of the platform is 321 metres (1,053 ft). However, this jump is rarely available, as part of the Royal Gorge Go Fast Games—first in 2005, then again in 2007. Previous to this the record was held in West Virginia, USA, by New Zealander Chris Allum, who bungee jumped 251 metres (823 ft) from the New River Gorge Bridge on "Bridge Day" 1992 to set a world's record for the longest bungee jump from a fixed structure.

Variations

Catapult

Main article: Reverse bungeeIn "Catapult" (Reverse Bungee or Bungee Rocket), the jumper starts on the ground. The jumper is secured and the cord is stretched, then released and shooting the jumper up into the air. This is often achieved using either a crane or a hoist attached to a (semi-)perma structure. This simplifies the action of stretching the cord and later lowering the participant to the ground.

Trampoline

"Bungy Trampoline" uses elements from bungy and trampolining. The participant begins on a trampoline and is fitted into a body harness, which is attached via bungy cords to two high poles on either side of the trampoline. As they begin to jump, the bungy cords are tightened, allowing a higher jump than could normally be made from a trampoline alone.

Running

"Bungee Running" involves no jumping as such. It merely consists of, as the name suggests, running along a track (often inflatable) with a bungee cord attached. One often has a velcro-backed marker that marks how far the runner got before the bungee cord pulled back. This activity can often be found at fairs and carnivals and is often most popular with children.

Ramp

Bungee jumping off a ramp. Two rubber cords – the "bungees" – are tied around the participant's waist to a harness. Those bungee cords are linked to steel cables along which they can slide due to stainless pulleys. The participants bicycle, sled or ski before jumping.

SCAD diving

SCAD diving (Suspended Catch Air Device) is similar to bungee jumping in that the participant is dropped from a height, but in this variation there is no cord; instead the participant free-falls into a net. Untrained SCAD divers use a special free fall harness to ensure the correct falling position. Free-style SCAD divers do not use harnesses. The landing into the huge airtube framed net is extremely soft and forgiving. The SCAD was invented by MONTIC Hamburg, Germany in 1997.

Risk of injury

Bungee jumping injuries may be divided into those that occur after jumping secondary to equipment mishap or tragic accident, and those that occur regardless of safety measures.

In the first instance, injury can happen if the safety harness fails, the cord length is miscalculated, or the cord is not properly connected to the jump platform. In 1986, a man died during rehearsals for a bungee jumping stunt on a BBC television programme, because the cord sprang loose from a carabiner clip.

Injuries that occur despite safety measures generally relate to the abrupt rise in upper body intravascular pressure during bungee cord recoil. Eyesight damage is the most frequently reported complication. Impaired eyesight secondary to retinal haemorrhage may be transient or take several weeks to resolve. In one case, a 26-year-old woman's eyesight was still impaired after 7 months. Whiplash injuries may occur as the jumper is jolted on the bungee cord and in at least one case, this has led to quadriplegia secondary to a broken neck. Very serious injury can also occur if the jumper's neck or body gets entangled in the cord. More recently, carotid artery dissection leading to a type of stroke after bungee jumping has also been described.

In popular culture

In the film GoldenEye and its associated videogame, James Bond makes a jump over the edge of a dam in Russia (in reality the dam is in Switzerland: Verzasca Dam, and the jump was genuine, not an animated special effect). The jump in the dam later makes an appearance as a Roadblock task in the 14th season of the reality competition series The Amazing Race.

A fictional proto-bungee jump is a plot point in the Michael Chabon novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay.

In the film Selena, in which Jennifer Lopez plays Selena Quintanilla-Perez, her character is shown bungee jumping at a carnival. This actual event took place shortly before Selena's murder on 31 March 1995.

In Valiant (comics) #171 (January 8, 1966), the two boys from Worrag island in "The Wild Wonders" in a circus story, jump from high up and seem ready to crash to their deaths, but are stopped by elasticated ropes tied to an ankle of each one.

In the video game Aero the Acro-Bat, Aero will perform bungee jumping to obtain items like keys to open gates in a level.

See also

- rope jumping, version of bungee jumping with a climbing rope

References

- Kockelman JW, Hubbard M. Bungee jumping cord design using a simple model. Sports Engineering 2004; 7(2):89–96

- "Home : Oxford English Dictionary". www.oed.com. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 16 January 2020.(subscription required)

- "bungee – definition of bungee in English | Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on 29 September 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "The People of Paradise: The Land Divers of Pentecost". BBC Television. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2013. First broadcast on 21 April 1960.

- AJ Hackett (2008). History Archived 17 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- "Vanuatu, Cradle of Bungee Jumping, May Finally Get Just Recognition". Time. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- Eric Larson, 2003 p135, The Devil in the White City; Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair that Changed America. Citing Chicago Tribune, 9 November 1889.

- "The Cliff Jumpers". LIFE magazine. 6 September 1963. p. 43. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- "David Kirke obituary". thetimes.com. 27 October 2023. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ "World's 'first' bungee jump in Bristol, England, captured on film". BBC. 10 November 2014. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- Martin, Brett (5 August 2013). "The Muddled Legacy of Oxford University's Dangerous Sports Club". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ "Geoff Tabin – Secret Life of Scientists and Engineers". Secret Life of Scientists and Engineers. PBS. 25 March 2014. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- Aerial Extreme Sports (2008). History of Bungee. Retrieved 17 October 2008. Archived 28 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Oxford University Dangerous Sports Club Golden Gate Bridge". Getty Images. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- Roberts, David (1986). Moments of Doubt. The Mountaineers. p. 218.

- "Allan John 'AJ' Hackett". Eyes On New Zealand - www.eyesonnewzealand.com. 30 May 2024. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- "Can you Hackett?". Unlimited – Inspiring Business. 23 August 2004. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- "AJ Hackett Bungy". Bungy.co.nz. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- "Bungee Jumping at the Bloukrans Bridge". My Guide Garden Route. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- "Bungee Condoms". Trendhunter.

- "World record bungy jump at Albufeira Marina". Algarve Daily News.

- "Guinness World Record – the Highest Commercial Decelerator Descent". Intercommunicate. 17 August 2005. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- "Kushma Bungee Jump". hikeontreks. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- Young, Jay (Fall 2020). Highland Outdoors.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - "Bungee Rocket BASE Jump – Wow!".

- "Scad Diving". Extreme Dreams – Dean Dunbar blind extreme sports. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- "Another extreme sport to enjoy?". 5 June 2008. Archived from the original on 1 December 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- McMenamin, Jennifer (16 May 2000). "Relatives grieve after fatal bungee accident". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on 7 October 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- Krott R, Mietz H, Krieglstein GK. Orbital emphysema as a complication of bungee jumping. Medical Science Sports Exercise 1997;29:850–2.

- Vanderford L, Meyers M. Injuries and bungee jumping. Sports Medicine 1995;20:name="ReferenceB">van Rens E. Traumatic ocular haemorrhage related to bungee jumping. Br J Ophthalmol 1994;78:948

- ^ Chan J. Ophthalmic complications after bungee jumping. Br J Ophthalmol 1994;78:239

- Filipe JA, Pinto AM, Rosas V, et al. Retinal complications after bungee jumping. Int Ophthalmol 1994–95;18:359–60

- Jain BK, Talbot EM. Bungee jumping and intraocular haemorrhage. Br J Ophthalmol 1994;78:236–7.

- David DB, Mears T, Quinlan MP. Ocular complications associated with bungee jumping. Br J Ophthalmol 1994;78:234–5

- van Rens E. Traumatic ocular haemorrhage related to bungee jumping. Br J Ophthalmol 1994;78:948

- Hite, Pamela R; Greene, Karl A; Levy, David I; Jackimczyk, Kenneth (June 1993). "Injuries resulting from bungee-cord jumping". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 22 (6): 1060–1063. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(05)82752-0.

- Zhou W, Huynh TT, Kougias P, El Sayed HF, Lin PH. Traumatic carotid artery dissection caused by bungee jumping. J Vascular Surg 2007;46:1044-6

- Iguana Entertainment (1 August 1993). Aero the Acrobat (Sega Genesis). Sunsoft. Level/area: Do The Bungee.

Further reading

- Srinivasan, Prianka (13 January 2020). "Bungee jumping came from Vanuatu — now Indigenous groups want to protect their customs". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

External links

Media related to Bungee jumping at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bungee jumping at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of bungee jumping at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of bungee jumping at Wiktionary- "Tourist dies in China after completing world's second highest bungy jump in China (photo)". Fairfax/Stuff. 2023.

- "Tourist dies at second highest bungy jump in world run by AJ Hackett (in China, photo)". MSN. 2023.

| Extreme and adventure sports | |

|---|---|

| Boardsports | |

| Motorsports | |

| Water sports | |

| Climbing | |

| Falling | |

| Flying | |

| Cycling | |

| Rolling | |

| Skiing | |

| Sledding | |

| Others | |