| California flying fish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Conservation status | |

Least Concern (IUCN 3.1) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Beloniformes |

| Family: | Exocoetidae |

| Genus: | Cheilopogon |

| Species: | C. pinnatibarbatus |

| Subspecies: | C. p. californicus |

| Trinomial name | |

| Cheilopogon pinnatibarbatus californicus (J. G. Cooper, 1863) | |

| Synonyms | |

| Cypselurus californicus | |

The California flying fish, Cheilopogon pinnatibarbatus californicus, is a subspecies of Bennett's flying fish, Cheilopogon pinnatibarbatus. Prior to the 1970s, the California flying fish was known as a distinct species, with the scientific classification Cypselurus californicus. The California flying fish is one of 40 distinct classifications of flying fish. It is the largest member of the flying fish family, growing up to 19 inches (48 cm) in length. It is a marine species found in the Eastern Pacific Ocean, from Oregon to Baja California. As with all other flying fish, the California can not actually fly, it launches itself into the air, using its specially adapted fins to glide along the surface. The California flying fish spends most of its time in the open ocean but comes close to shore at night to forage and lay eggs in the protection of kelp beds.

Taxonomy and Etymology

The California flying fish has gone through various scientific name changes over the years. It was first described by naturalist James Graham Cooper in 1864 as Cypselurus californicus. It was then renamed to Cypsilurus californicus by Jordan and Evermann in 1898, and slightly modified again to Cypselurus californicus in 1907 by Starks and Morris. The California flying fish underwent a major name change in 1944, described by Fowler as Parexocoetoides vanderbilti. Today, the California flying fish is classified as Cheilopogon californicus. Cheilopogon originates from the Greek words cheilos and pogon, cheilos meaning lip, and pogon meaning barbed or bearded. This most likely refers to the large barbel on the mouth of juvenile flying fish. The oldest known "flying" relative of the California flying fish, Potanichthys xingyiensis, was discovered in 2013 by paleontologists in southwest China. Potanichthys xingyiensis is a member of Thoracopteridae, an extinct family of bony fish that existed during the Triassic period.

| California Flying Fish

Temporal range: Eocene–Present | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Beloniformes |

| Suborder: | Exocoetoidei |

| Superfamily: | Exocoetoidea |

| Family: | Exocoetidae |

Habitat and Distribution

California flying fish live in the Eastern Pacific Ocean, ranging from Oregon to Baja California. The mean sea surface temperature is the largest factor in determining where flying fish live. Their flight is energetically limited by water temperature, so their population richness is limited to southern California and Baja California waters. Data shows that their top speed is ten meters per second, which can only be achieved at temperatures above 20 degrees Celsius. As a result, flying fish prefer tropical and temperate climates. The Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean (ETP) supports the vast majority of this species and their predators. They do not have a niche diet and can find cyanobacteria and small eukaryotes almost anywhere. Thus their habitat at a taxonomic scale spans not only the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of the United States but also the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans. California flying fish live in the epipelagic zone, the top 200 meters of the ocean where there is ample sunlight. They are also neritic, meaning that they live in more shallow areas of the ocean.

Life Stages and Reproduction

All flying fish are oviparous, meaning they reproduce by laying eggs rather than giving birth to live young. California flying fish undergo multiple stages of development: the egg, larval, juvenile, and adult stages.

Egg

California flying fish lay their eggs on kelp beds. Their eggs have been observed to have about 60 adhesive filaments, structures that help the egg attach to surfaces like kelp and other debris in the open ocean. Their ova is about 1.64 mm in diameter.

Larval

At the larval stage, they have a yolk sac, which functions as a source of nutrients for the young fish. There are also important hormones and enzymes stored in the yolk for the developing fish. Their mouth is inferior, or subterminal. Their body is heavily pigmented with cells called melanophores. The dorsal and anal fin are still connected to the caudal fin. These fins are separated as the fish grows.

Juvenile

Juvenile California flying fish can easily be spotted by their large barbel, a sensory organ near the mouth of the fish. It is made up of 14 flaps that make a fan-like shape. The barbel is lost as the fish matures into an adult. At this stage, their mouth develops into a superior mouth type, which is useful for eating at the top of the water column. The snouts of juvenile California flying fish are shorter than the snouts of adults. Juveniles can also be distinguished by their elevated dorsal fin, which are much larger in comparison to the rest of their fins. Juveniles often have dark blotches around their rays, which are lost by the time they reach the adult stage. Compared to adults, the bodies of juvenile California flying fish are more slender.

Adult

Adult California flying fish have a blue-grey body with a silver underbelly. They have clear pectoral fins and a dark grey caudal fin. Adults have a shorter dorsal fin compared to juveniles. They do not have a barbel. At this stage, the snout is still relatively short, but still longer in comparison to a juvenile.

Otolith analysis has been successfully used in other species of flying fish to determine their age and growth rates. There is no current data on the lifespan of the California flying fish, however, flying fish in general are believed to live for about 5 years.

Ecology

Flying fish are large enough to eat zooplankton, but small enough to be consumed by top predators. For this reason, flying fish form a central mid-trophic component on epipelagic oceanic food webs. California flying fish are mainly preyed upon by squid and large fish like tuna. They make up a large part of the diet of dolphinfish who live near the California coast. There have also been accounts of pelagic seabirds such as the black-footed albatross catching flying fish.

Adult California flying fish have a superior mouth type, meaning they are upturned. This mouth shape is useful for eating food at the top of the water column. As a result, their diet mainly consists of plankton, fish larvae, and fish eggs.

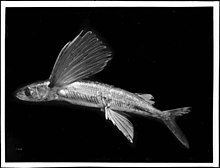

Anatomy

California flying fish have 9–13 dorsal rays and 9–12 anal rays. They have a deeply forked caudal fin with the bottom lobe larger than the top lobe. Their lateral line, an organ that helps fish detect movement in the water, is located relatively low on the body. Their scales are large and smooth, contributing to this fish's shiny appearance. They have only about 50 scales located in front of their dorsal fin. They have 48–51 vertebrae and 10–12 branchiostegal rays.

"Flight" Mechanics

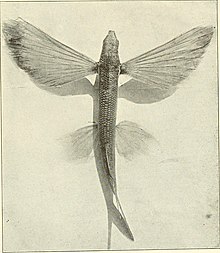

The California flying fish's key characteristic is that it is seen to be able to "fly". Although their name is "flying" fish, the California flying fish is technically incapable of flight. To fly, California flying fish begin by swimming rapidly while spreading their pectoral fins. They do this while quickly moving their caudal fin back and forth to supply power. Their pectoral fins are not used for flapping, rather they are used to support the fish while in the air. At a speed of over 56 kilometers (35 miles) per hour, they propel themselves out of the water. Then, as they begin to enter the air, they stop moving the caudal fin and begin to glide. Those who have observed the California flying fish in the air have noted that they come out of the water moving at a high speed, rather than jumping directly into the air from a resting position. The length of a flight averages 25 feet (7.6 meters), with a height capping out at approximately 5 feet (1.5 meters). California flying fish typically make up to five successive flights of decreasing distance and height at a time.

The flying fish's evolutionary streamlined body (which reduces drag) and winglike pectoral fins (that can be laid flat) allow for this species of fish to "fly". Flying fish can be classified into two aerodynamic designs, monoplane and biplane. California flying fish are biplane, meaning they have two sets of "wings". Their pectoral fins function as their main set of wings, which stay in the air as they "fly". The pelvic fins function as the underwings; they glide along the water to lift the fish into the air. Their wings are made up of bony fin rays that are covered by a soft membrane. The upper parts of the wing have a smooth surface, while the undersides have a ribbed structure that provides support.

It is relatively rare for a species to be well-evolved for both swimming and flying. It is especially interesting to note that California flying fish are considered large for a fish that is able to glide. To be energetically efficient in the water, it is beneficial to have a body type that minimizes drag, which slows the fish down. However, in order to effectively fly, features that allow lift are more beneficial. Evolving a feature that is beneficial for efficient swimming may hurt the chances of flying effectively, and vice versa.

There are various theories on why flying fish evolved to glide in the air. One widely accepted theory is that they evolved to escape predators in the water. Another theory is that it is more energy-efficient for fish to glide through the air when they need to travel at great speeds or distances. The drag experienced in the air is often less than that of the water, making it a reasonable hypothesis that gliding evolved as an energy-saving tactic. Some researchers believe that their gliding is similar to the act of porpoising in aquatic animals like dolphins. Generally, the reasons for leaping behavior in the water have not been concretely proven, and are still up for debate.

Conservation

The California flying fish is currently classified by the IUCN as Least Concern. There are currently no listed major threats to the California flying fish. California flying fish are said to have a very pungent odor, so they are not caught for human consumption. However, flying fish will occasionally be used as bait by recreational fishers. Some artificial flying fish lures have been developed as an alternative to live bait. However, this is not a widespread practice among fishers. There is one known fishery in southern California that sells frozen flying fish as bait for various species of tuna. These are not collected on a mass scale, however. Fishers capture the flying fish by hand with small dipnets. There have been cases where flying fish were reported to jump onto well-lit boats, attracted by the light.

Even though the California flying fish population does not face any significant direct threats from humans, human-induced climate change will inevitably have an effect on flying fish. Climate change has been shown to have an impact on plankton population density. The California flying fish heavily relies on plankton as a food source, so if climate change were to significantly impact plankton, this could affect the California flying fish.

As of now, there have not yet been any conservation measures established specifically for the California flying fish. There are various marine protected areas, however, that overlaps with their native range. Abundance data specifically on the California flying fish has not been reported.

Cultural Significance

The California flying fish is especially culturally significant to Catalina Island, an island located near Los Angeles, California. Catalina Island previously had an annual flying fish festival held from late May to early June. Though this festival is no longer held, the island has other ways of celebrating the arrival of the California flying fish. During the summer months, various tours are offered to see the flying fish from small boats. These tours are often offered at night, and lights are shined down into the water to attract plankton. Since plankton makes up a large percentage of the California flying fish's diet, the fish are attracted to the area for tourists to see.

References

- Collette, B. (2010). "Cheilopogon pinnatibarbatus ssp. californicus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2010: e.T184053A8229048. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-3.RLTS.T184053A8229048.en. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ^ "Flying Fish". National Wildlife Federation.

- ^ Hubbs, C.L.; Kamps, E.M. (1946). "The Early Stages (Egg, Prolarva and Juvenile) and the Classification of the California Flyingfish". Copeia. 4 (1946): 188–218. doi:10.2307/1438107.

- ^ "California flyingfish". Fish Base. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- Xu, G.; Zhao, L.; Gao, K.; Wu, F. (January 2013). "A new stem-neopterygian fish from the Middle Triassic of China shows the earliest over-water gliding strategy of the vertebrates". Proc Biol Sci. 280 (1750). doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.2261. PMC 3574442.

- ^ Lewallen, Eric A.; van Wijnen, Andre J.; Bonin, Carolina A.; Lovejoy, Nathan R. (December 2018). "Flyingfish (Exocoetidae) species diversity and habitats in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean". Marine Biodiversity. 48 (4): 1755–1765. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1990.tb04009.x.

- Lewallen, Eric; Pitman, Robert; Kjartanson, Shawna; Lovejoy, Nathan (December 2010). "Molecular systematics of flyingfishes (Teleostei: Exocoetidae): evolution in the epipelagic zone". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 102 (1): 161–174. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2010.01550.x. hdl:2027.42/79173.

- ^ "Smallhead Flyingfish". California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- Kamler, E. (2008). "Resource allocation in yolk-feeding fish". eviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries (18): 143–200. doi:10.1007/s11160-007-9070-x.

- ^ "Species: Cheilopogon californicus, California flyingfish, Smallhead flyingfish". Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- Oxenford, H.A.; Hunte, W.R.; Campana, D.; Campana, S.E. (1994). "Otolith age validation and growth-rate variation in flyingfish (Hirundichthys affinis) from the eastern Caribbean". Marine Biology. 118: 585–592. doi:10.1007/BF00347505.

- Fisher, H.I. (1945). "Black-footed Albatrosses Eating Flying Fish". The Condor. 47 (3): 128–129. doi:10.1093/condor/47.3.128.

- ^ Breder, C.M. Jr. (December 1930). "On the Structural Specilization of Flying Fishes from the Standpoint of Aerodynamics". Copeia. 1930 (4): 114–121. doi:10.2307/1436467.

- ^ Hubbs, C. (1918). "The Flight of the California Flying-Fish (Cypselurus californicus)". Copeia. 62: 85–88. doi:10.2307/1435974.

- Zool, J. (1990). "Wing design and scaling of flying fish with regard to flight performance". Journal of Zoology. 221 (3): 343–515. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1990.tb04009.x.

- Davenport, John (June 1994). "How and why do flying fish fly?". Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries. 4 (2): 184–214. doi:10.1007/BF00044128.

- Park, H.; Choi, H. (2010). "Aerodynamic characteristics of flying fish in gliding flight". Journal of Experimental Biology. 213 (19): 3269–3279. doi:10.1242/jeb.046052.

- ^ Rayner, J. (1986). "Pleuston: animals which move in water and air". Endeavour. 10 (2): 58–64. doi:10.1016/0160-9327(86)90131-6.

- ^ "Bennett's Flyingfish". IUCN. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ Kaiser, D. "Catalina's flying fish part of it's allure". The Catalina Islander. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- "About G-Fly Baits". G-Fly Premium Flying Fish. Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- "Marine Plankton Food Webs and Climate Change" (PDF). Virginia Institute of Marine Science.

- "Flying Fish". PBS SoCal. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

| Taxon identifiers | |

|---|---|

| Cheilopogon pinnatibarbatus californicus | |