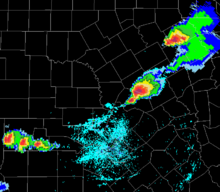

WSR-88D radar imagery of storms across Central Texas at 3:40 pm CDT on May 27, 1997 WSR-88D radar imagery of storms across Central Texas at 3:40 pm CDT on May 27, 1997 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Duration | 7 hours, 2 minutes |

| Tornado outbreak | |

| Tornadoes | 20 confirmed |

| Maximum rating | F5 tornado |

| Highest winds | Tornadic – >261 mph (420 km/h) (Jarrell F5 tornado) Non-tornadic – 122 mph (196 km/h) (Kelly Air Force Base, San Antonio, Texas, straight-line winds) |

| Largest hail | 4.50 in (114 mm) (Bell and Falls counties) |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 28 (+2 indirect) |

| Injuries | 33 |

| Damage | $126.6 million (1997 USD) |

| Areas affected | Central Texas |

| Power outages | ≥ 81,000 electricity customers |

Part of the tornado outbreaks of 1997 | |

A deadly tornado outbreak occurred in Central Texas during the afternoon and evening of May 27, 1997, in conjunction with a southwestward-moving cluster of supercell thunderstorms. These storms produced 20 tornadoes, mainly along the Interstate 35 corridor from northeast of Waco to north of San Antonio. The strongest tornado was an F5 tornado that leveled parts of Jarrell, killing 27 people and injuring 12 others. Overall, 30 people were killed and 33 others were hospitalized by the severe weather.

Although the atmospheric conditions enabling the event were forecast to be conducive for strong winds and large hail, forecasters did not initially anticipate as much of a risk of strong tornadoes due to the lack of substantial wind shear over the region. Instead, the coalescence of several weather features—including a cold front, a dry line, and a gravity wave—provided locally favorable conditions for rotating thunderstorms and the formation of tornadoes. This peculiar evolution led to the unusual southwestward motion of the storms and the tornadoes they produced.

A tornado watch was first issued at 12:54 p.m. on May 27 for portions of East Texas and western Louisiana; the first tornado touched down at 1:21 p.m. in McLennan County while the final tornado lifted at 8:23 p.m. later that day in Frio County. The 20 tornadoes collectively inflicted at least $126.6 million in damage. The F5 Jarrell tornado was the outbreak's most powerful and deadliest tornado. It destroyed most of the 38-home Double Creek Estates subdivision west of Jarrell where the most extreme damage occurred. Residences were completely dismantled, swept away, and reduced to concrete slabs, while trees in the area were completely shredded and debarked. Fields were scoured to a depth of 18 in (460 mm) and asphalt was torn from roads. Due to the tornado's intensity, the debris was often small in size and beyond recognition. There were four other tornadoes rated F3 or higher. One F3 tornado moved across Cedar Park, damaging parts of the business district and numerous homes in nearby neighborhoods. An F4 tornado struck areas near Lake Travis and caused one fatality. In addition to the tornadoes, the storms also produced large hail and strong straight-line winds; Kelly Air Force Base in San Antonio recorded a 122 mph (196 km/h) wind gust.

Meteorological synopsis

Atmospheric setup

The severity of the 1997 Central Texas tornado outbreak was predicated on an unusual spatial and temporal alignment of weather features at highly localized scales. The broader environment was not particularly anomalous for the late springtime over Central and East Texas. Unlike conventional tornado outbreaks in Texas, the 1997 outbreak was not associated with a strong trough of low pressure and strong density gradients in the lower troposphere. Instead, the most prominent weather system over the central U.S. at the time was a distant upper-level low centered over Nebraska imparting little influence on atmospheric conditions over Texas.

Consequently, winds in the mid-levels of the troposphere over Texas on May 27 were weak and westerly, ranging from 30 kn (35 mph; 56 km/h) over North Texas to below 15 kn (17 mph; 28 km/h) over Central and South Texas. Winds closer to the surface were also quiescent; the average storm-relative winds within the lowest 6 km (3.7 mi) of the atmosphere as measured in Del Rio, Texas, prior to the onset of storm development was only 6 kn (6.9 mph; 11 km/h). Further aloft at the level of the jet stream, there were two nearby wind speed maxima over northern Mexico and the central Mississippi Valley; this led to strong divergence of air over Texas. Wind shear was negligible within the lowest 6 km (3.7 mi) of the atmosphere contrary to typical tornado outbreaks.

Despite generally meager winds, the atmosphere was nonetheless thermally energetic. The combination of several days of onshore wind flow from the Gulf of Mexico and the persistence of a capping inversion aloft led to an accumulation of moist air over the state. Dew points soon exceeded 70 °F (21 °C) within the boundary layer, representing ample moisture in the lower levels of the troposphere. Radiosondes launched from Corpus Christi and Fort Worth on the morning of May 27 detected the presence of a robust "elevated mixed layer" of air aloft characterized by steep lapse rates—the change of temperature with height—near the dry adiabatic lapse rate. This contributed to high convective available potential energy (CAPE) exceeding 5,500 J/kg across most of Central and East Texas, denoting a highly unstable atmosphere. In some cases CAPE was as high as 6,500 J/kg. The lack of fronts moving across Texas in the 36 hours before the tornado outbreak allowed this instability to remain and spread across much of the state.

Although these conditions were regionally conducive to the development of thunderstorms capable of producing large hail and strong winds, the potential for supercell and tornado development was not initially clear given the lack of wind shear. Other metrics and indices used to diagnose tornado potential, such as the Energy Helicity Index, storm-relative helicity, supercell composite parameter, and the significant tornado parameter, were also lower than historically observed environments featuring tornadoes. For instance, the amount of storm-relative helicity within the lowest 3 km (1.9 mi) of the atmosphere—a common measure quantifying the amount of wind shear—was measured as 70 m/s at Corpus Christi and reached 117 m/s according to data from the Rapid Update Cycle computer model; values below 300 m/s are correlated with weak tornadoes. A study published in Monthly Weather Review in 2007 described the environment as being "marginally favorable for supercells and unfavorable for significant, supercellular tornadoes."

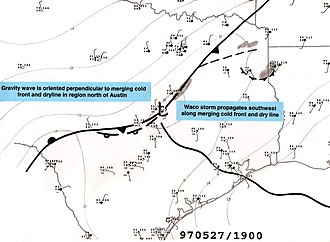

Instead, the factors that enabled the eventual tornado outbreak may have transpired at a mesoscale involving several features becoming juxtaposed over Texas. The dry line delineating the boundary between the moist maritime air mass over East Texas and the drier continental air mass farther west remained nearly stationary in the region through the morning of May 27. On the preceding evening, a mesoscale convective system developing along this dry line over eastern Oklahoma and Arkansas generated a well-defined gravity wave that traveled southwest across East Texas on the morning of May 27. Its progression was evidenced on satellite imagery as an advancing band of mid-level cumuli. A weak low-pressure area also developed along the dry line near Dallas and tracked southwest along the boundary. In the two days before May 27, a cold front associated with the upper-level low over Nebraska had swept slowly southeast across the central U.S. Prior to dawn on May 27, the front progressed across West Texas; by 7:00 a.m. on May 27, the front spanned from southeastern Oklahoma through the northwestern portion of the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex southwestwards to near the Big Bend of Texas. This placed the cold front parallel and just to the west of the dry line along a northeast to southwest orientation. A swath of clear skies emerged between the two boundaries, maximizing surface heating during the daytime and contributing to the weak low-pressure area's southwestward movement through Central Texas.

Development of storms

At around 12:30 p.m., the gravity wave, cold front, dry line, and low-pressure area overlapped near Waco, Texas, with the faster cold front overtaking and merging with the nearly stationary dry line. The cold front and dry line were brought together in a northeast to southwest fashion resembling a zipper. Thunderstorms formed near Waco in tandem with this juxtaposition of features and within a local maximum of surface heating and convergence of moist air. While some storms had spawned along the cold front, the gravity wave's passage in the early afternoon hours coincided with a rapid intensification of the first thunderstorms. The arrival of the gravity wave and its perpendicular alignment relative to the orientation of the cold front and dry line may have enhanced wind shear locally despite weak wind shear at a broader, synoptic scale. This allowed the thunderstorms to rotate and become supercells.

However, the degree to which the wave contributed to the formation of supercells and eventually tornadoes remains a subject of disagreement among meteorologists. The development of new discrete supercells followed the advancing intersection of the cold front and dry line and the gravity wave as they continued southwest, though each individual storm was nearly stationary. Due to the westerly winds in the mid-levels of the troposphere, the outflow from each developing storm was directed east, allowing each new thunderstorm to develop and rotate without interference from the initial storms. The direction of the storms' expansion towards the southwest deviated over 100 degrees away from these westerly winds, representing an extreme and highly unusual motion. The southwestward generation of storms brought them towards increasingly unstable air with higher CAPE, allowing the storms to acquire strong inflow and the requisite rotation to produce tornadoes.

There were at least three families of thunderstorms that developed as part of the initial southwestward-moving complex of storms, composed of at least 16 distinct supercells; six of the cells formed along the cold front, five formed along the dry line, and five formed along the gust front imparted by previous storms. The gust fronts pushed outwards by the downdrafts of the thunderstorms served as foci for tornadogenesis; boundaries like gust fronts can provide low-level vorticity and rising air necessary for the formation of tornadoes. Some of the day's tornadoes were spun up by the gust front itself while others spawned from thunderstorms with preexisting mesocyclones aloft enhanced by the gust front underneath.

The day's first thunderstorm near Waco in McLennan County strengthened quickly in response to the highly unstable atmosphere. A severe thunderstorm warning—the first of the day—was issued for the county at 12:50 p.m. Weather radars showed increasing rotation within the storm, prompting the issuance of a tornado warning at 1:21 p.m. This storm produced the outbreak's first tornado 5 mi (8.0 km) southwest of Hewitt near Lorena. The same storm produced a second brief tornado near Bruceville followed by a third, intense F3 tornado in southwestern McLennan County that lasted for 20 minutes. A new thunderstorm developed along the flanking line associated with the first storm. This second storm spawned several tornadoes as it expanded towards the southwest, including an F3 tornado near Lake Belton beginning at 2:25 p.m. and the F5 Jarrell tornado beginning at 3:25 p.m. The NEXRAD radar in Granger used to monitor this storm suffered a power failure and went out of commission at 3:38 p.m. A control switch left in an improper position on a prior maintenance visit prevented its emergency power supply from activating. Thunderstorms developing to the southwest later in the afternoon and evening produced additional tornadoes, including the F3 tornado that struck Cedar Park and the F4 tornado that struck Lakeway. The Lakeway tornado was the first instance of an F4 tornado striking Travis County on record. The final tornado of the day touched down in Frio County and lifted at 7:23 p.m.

Farther south away from the southwestward-moving storm cluster, the cold front and dry line curved west, making them parallel to the advancing gravity wave; this triggered the development of numerous and intense storms between Austin and the Big Bend after 3:00 p.m. when the gravity wave intersected the front. The parallel orientations of the wave and the other boundaries precluded these storms' rotation. They tracked east and eventually merged with the southwestward-propagating complex of tornadic storms along the Pedernales River. This coalescence produced a south- and southeastward-moving squall line and ended the strong tornado activity. Nonetheless, strong and damaging winds were produced by the squall line for several hours. Kelly Air Force Base in San Antonio documented a wind gust of 106 kn (122 mph; 196 km/h), marking a record high wind velocity for the site.

Warnings and preparedness

The Storm Prediction Center (SPC) forecasted a moderate risk for severe thunderstorms over parts of East Texas in its severe weather outlook issued at 1:03 a.m. on May 27. The moderate risk region included Waco, the Killeen–Temple–Fort Hood metropolitan area, and extended east towards Shreveport, Louisiana, and Fort Polk, Louisiana. Austin was located at the boundary between the moderate risk region and the slight risk region that encompassed most of East and South Texas, including the Hill Country. The SPC predicted that the gravity wave would be a focal point for storms capable of producing large hail and damaging winds given the unstable atmosphere. A subsequent outlook issued by the SPC at 10:16 a.m. continued to indicate a moderate risk for severe weather and mentioned the possibility of isolated and brief tornadoes. A tornado watch was later issued by the SPC at 12:54 p.m. for parts of eastern Texas and western Louisiana, citing the unstable airmass in place over the region. The Dallas/Fort Worth and Austin/San Antonio National Weather Service forecast offices also issued bulletins on the morning of May 27 noting the potential for severe weather. However, these early outlooks focused more on the threat of wind and hail rather than tornadoes due to the low wind shear present over the region.

The Dallas/Fort Worth National Weather Service forecast office ultimately issued 10 tornado warnings and 5 severe thunderstorm warnings between 1 and 5 p.m. on May 27. The Austin/San Antonio office issued 8 tornado warnings, 24 severe thunderstorm warnings, and 10 flash flood warnings during the afternoon and evening of May 27, with 80 percent of their issued products occurring after 5 p.m. in connection with the widespread storms that developed later in the day separate from the initial tornadic storms. In one case, a media outlet's decision to manually activate the Emergency Alert System rather than allow weather warnings to automatically trigger it resulted in a 25–30 minute delay in the dissemination of a warning. Interviews conducted by a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration service assessment team found that many watched the approach of tornadoes prior to taking shelter due to their slow movement and high visibility. In the case of the F5 Jarrell tornado, some fled while others took shelter. Due to the strength of the tornado, some who stayed behind were killed despite taking appropriate safety measures.

Confirmed tornadoes

| FU | F0 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 20 |

| F# | Location | County | Start Coord. | Time (UTC) | Path length | Max width | Damage | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F2 | W of Lorena | McLennan | 31°23′N 97°19′W / 31.38°N 97.32°W / 31.38; -97.32 (Lorena (May 27, F2)) | 18:21 – 18:33 | 2 mi (3.2 km) | 75 yd (69 m) | $75,000 | Several large trees were uprooted and a mobile home was destroyed. |

| F0 | Eddy area | McLennan | 31°18′N 97°15′W / 31.30°N 97.25°W / 31.30; -97.25 (Eddy (May 27, F0)) | 18:44 – 18:47 | 0.2 mi (0.32 km) | 40 yd (37 m) | — | Tornado reported by a sheriff deputy caused no damage. |

| F3 | E of Moody | McLennan, Bell | 31°16′N 97°21′W / 31.27°N 97.35°W / 31.27; -97.35 (Moody (May 27, F3)) | 18:46 – 18:59 | 3.7 mi (6.0 km) | 150 yd (140 m) | $150,000 | Most of the tornado's path occurred in McLennan County. A home and a barn were destroyed on Dowell Road after the tornado initially touched down in open terrain near Farm to Market Road 107; these structures received F3 tornado damage. Another home nearby was also damaged and a pickup truck and car were displaced by several hundred feet. The tornado moved south-southwest, crossing the border between McLennan and Bell counties and traversing open country. There, numerous trees were uprooted. A local news station also captured this tornado and much of its life cycle as it passed within a few miles of their skycam and station. |

| F0 | WNW of Belton | Bell | 31°05′N 97°32′W / 31.08°N 97.53°W / 31.08; -97.53 (Belton (May 27, F0)) | 19:16 – 19:27 | 0.2 mi (0.32 km) | 50 yd (46 m) | — | Weak tornado remained stationary for much of its existence before dissipating. |

| F3 | N of Belton | Bell | 31°10′N 97°28′W / 31.17°N 97.47°W / 31.17; -97.47 (Belton (May 27, F3)) | 19:27 – 19:45 | 1.4 mi (2.3 km) | 275 yd (251 m) | $900,000 | The tornado began on the northern shores of Lake Belton at Morgan's Point Resort. A marina was destroyed on the lake's northern shores, leading to the capsizing of 100 boats. Ten homes along the same shore sustained severe damage and trees were destroyed. The tornado then crossed the lake and moved ashore northeast of the community of Woodland, downing many trees and causing heavy damage to at least six structures. The tornado was on the ground for a third of a mile after traversing the lake before lifting. |

| F1 | SW of Belton | Bell | 31°01′N 97°32′W / 31.02°N 97.53°W / 31.02; -97.53 (Belton (May 27, F1)) | 19:50 – 19:58 | 0.2 mi (0.32 km) | 40 yd (37 m) | — | Brief tornado with unknown damage. |

| F1 | Blooming Grove area | Navarro | 32°06′N 96°43′W / 32.10°N 96.72°W / 32.10; -96.72 (Blooming Grove (May 27, F1)) | 20:05 – 20:10 | 0.5 mi (0.80 km) | 50 yd (46 m) | — | Brief tornado uprooted several large trees. |

| F1 | NW of Prairie Dell | Bell | 30°54′N 97°35′W / 30.90°N 97.58°W / 30.90; -97.58 (Prairie Dell (May 27, F1)) | 20:07 – 20:25 | 2.4 mi (3.9 km) | 100 yd (91 m) | $20,000 | Initially stationary tornado that began to quickly track towards the south-southwest, destroying trees and damaging several structures. |

| F2 | N of Jarrell | Williamson | 30°53′05″N 97°35′38″W / 30.8848°N 97.594°W / 30.8848; -97.594 (Jarrell (May 27, F2)) | 20:25 – 20:33 | 2 mi (3.2 km) | 200 yd (180 m) | — | First of two tornadoes that preceded the Jarrell F5 tornado. |

| F2 | NW of Jarrell | Williamson | 30°52′05″N 97°36′11″W / 30.868°N 97.603°W / 30.868; -97.603 (Jarrell (May 27, F2)) | 20:35 – 20:39 | 0.5 mi (0.80 km) | 150 yd (140 m) | — | Second of two tornadoes that preceded the Jarrell F5 tornado; classified as a multi-vortex tornado. |

| F1 | S of Dawson | Navarro | 31°52′N 96°43′W / 31.87°N 96.72°W / 31.87; -96.72 (Dawson (May 27, F1)) | 20:36 – 20:40 | 0.5 mi (0.80 km) | 50 yd (46 m) | — | Brief tornado uprooted large trees. |

| F5 | W of Jarrell | Williamson | 30°50′24″N 97°37′05″W / 30.84°N 97.618°W / 30.84; -97.618 (Jarrell (May 27, F5)) | 20:40 – 20:53 | 5.1 mi (8.2 km) | 1,320 yd (1,210 m) | $40.1 million | 27 deaths – See article on this tornado – 12 others were injured. |

| F0 | SW of Hubbard | Hill | 31°49′N 96°50′W / 31.82°N 96.83°W / 31.82; -96.83 (Hubbard (May 27, F0)) | 20:50 – 20:53 | 0.2 mi (0.32 km) | 40 yd (37 m) | — | Brief tornado caused no damage. |

| F3 | Cedar Park | Williamson, Travis | 30°33′N 97°49′W / 30.55°N 97.82°W / 30.55; -97.82 (Cedar Park (May 27, F3)) | 21:05 – 21:15 | 9.2 mi (14.8 km) | 200 yd (180 m) | $70.11 million | This tornado moved south through Cedar Park before crossing into Travis County and lifting just northeast of Mansfield Dam. The thunderstorm that spawned the tornado developed along the flanking line of the storm that produced the F5 tornado in Jarrell. It initially touched down in an open area, causing minor shingle damage to a house and damaging a few trees. Before moving into Cedar Park, the tornado caused F1 and F2 damage. Localized F3 damage occurred within Cedar Park's business district. Most of the roofing on an Albertsons grocery store was torn away; the store's walls and doors were also severely damaged or destroyed. At least seven people were injured in the store and one person was hospitalized, though additional injuries were mitigated by the sheltering of customers in the store's refrigeration units under the direction of the store's manager. Several businesses were damaged along US-183; one business lost most of its roof, though damage to most other businesses was minor. A 65,000-pound (29,000 kg) coal tender converted to hold diesel fuel was flipped over and thrown a short distance after a historic train was struck near the highway. The tornado then moved into the Buttercup Creek subdivision in southwestern Cedar Park, inflicting F1–F3 damage to 136 homes. Some homes sustained significant roof loss and severe structural damage; eleven were destroyed. It then curved towards the southwest into Travis County and downed ten percent of trees in a wooded area before lifting 1.1 miles (1.8 km) north of Lake Travis. Fifteen people were injured by the tornado. |

| F1 | NW of Four Points | Travis | 30°24′N 97°51′W / 30.40°N 97.85°W / 30.40; -97.85 (Four Points (May 27, F0)) | 21:15 – 21:15 | 0.2 mi (0.32 km) | 20 yd (18 m) | $5,000 | Brief tornado with minimal damage. |

| F4 | W of Lakeway | Travis | 30°22′N 98°01′W / 30.37°N 98.02°W / 30.37; -98.02 (Lakeway (May 27, F4)) | 21:50 – ? | 5.6 mi (9.0 km) | 440 yd (400 m) | $15 million | 1 death – The tornado touched down near the shore of Lake Travis, destroying a marina and most of the watercraft at the docks. Trees in the area were contorted and uprooted, though other nearby structure sustained minor damage of F0 severity. Numerous structures sustained varying degrees of damage as the tornado moved westward and later southwestward, including a Southwest Bell telephone building on Bee Creek Road that was destroyed and a home across the road that had several collapsed walls. The destruction of the well-constructed telephone building warranted an F4 rating. The tornado then made a turn towards the southwest roughly 2.2 miles (3.5 km) from Lake Travis, bringing it across a hill where buildings and trees were destroyed. Further southwest, a steel tower carrying high transmission power lines was destroyed. Additional site-built homes, mobile homes, and other buildings were either heavily damaged or completely destroyed in the Hazy Hills subdivision, leaving many uninhabitable. This included well-built homes within the subdivision. One person was killed following the destruction of his mobile home and vehicle, though investigators could not establish whether he was in the home or attempting to evacuate when the tornado struck. The tornado crossed Texas State Highway 71, entering another subdivision near Lick Creek and causing as high as F2 tornado damage to structures in the area, including the complete unroofing of one house near Pedernales Drive. Throughout the tornado's path, numerous trees were downed and 25 homes were destroyed; five people were injured. |

| F1 | N of Kyle | Hays | 30°01′N 97°52′W / 30.02°N 97.87°W / 30.02; -97.87 (Kyle (May 27, F1)) | 22:38 – 22:45 | 3.5 mi (5.6 km) | 60 yd (55 m) | $5,000 | Trees and power lines were knocked over. |

| F0 | S of Utopia | Uvalde | 29°31′N 99°32′W / 29.52°N 99.53°W / 29.52; -99.53 (Utopia (May 27, F0)) | 00:00 – 00:03 | 0.2 mi (0.32 km) | 20 yd (18 m) | — | Tornado remained over open country. |

| F0 | NW of Sisterdale | Kendall | 29°59′N 98°45′W / 29.98°N 98.75°W / 29.98; -98.75 (Sisterdale (May 27, F0)) | 00:30 – 00:32 | 0.7 mi (1.1 km) | 30 yd (27 m) | — | Tornado remained over open country. |

| F0 | NE of Moore | Frio | 29°04′N 99°00′W / 29.07°N 99.00°W / 29.07; -99.00 (Moore (May 27, F0)) | 01:20 – 01:23 | 1 mi (1.6 km) | 40 yd (37 m) | — | Tornado remained over open country. |

Jarrell, Texas

Main article: 1997 Jarrell tornado One of the photos of the "Dead Man Walking" photo sequence of the tornado. One of the photos of the "Dead Man Walking" photo sequence of the tornado. | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | May 27, 1997, 3:40 pm. CDT (UTC−05:00) |

| Dissipated | May 27, 1997, 3:53 pm. CDT (UTC−05:00) |

| Duration | 13 minutes |

| F5 tornado | |

| on the Fujita scale | |

| Highest winds | >261 mph (420 km/h) |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 27 |

| Injuries | 12 |

| Damage | $40.1 million (1997 USD) |

Parts of Jarrell, Texas, were struck by an extremely powerful F5 tornado on the afternoon of May 27. The tornado destroyed approximately 10 percent of the homes in Jarrell; at the time, the city had a population of about 450 people and had been previously struck by tornadoes in 1987 and 1989. Hardest-hit was the Double Creek Estates subdivision west of downtown Jarrell. The 1997 Jarrell tornado was the first and only known occurrence of an F5 tornado in Williamson County. It was also the deadliest tornado in Texas since the 1987 Saragosa tornado. The thunderstorm that spawned the Jarrell tornado began west of Temple along the flanking line of another thunderstorm earlier in the afternoon of May 27. The storm produced several tornadoes in Bell County, including the F3 tornado that impacted communities along Lake Belton. Weather radar observed a strengthening mesocyclone within the thunderstorm, with the speed of rotation rising above 40 kn (46 mph; 74 km/h). As the storm moved into Williamson County, it produced two short-lived F2 tornadoes north of Jarrell at 3:25 p.m. and 3:35 p.m.; the latter of the two was a multiple-vortex tornado and lifted at 3:39 p.m. The Austin/San Antonio National Weather Service forecast office issued a tornado warning for Williamson County at 3:30 p.m. in response to the storm's approach; the warning was put into effect for one hour. This was the first tornado warning of the day issued for the office's warning area and warned that "the city of Jarrell is in the path of this storm." Local warning sirens went off about 10–12 minutes before the tornado struck.

The precise start of the Jarrell tornado was difficult to pinpoint. The most prominent and destructive part of the tornado's evolution was preceded by the apparition of short-lived, small, and rope-like funnel clouds. These may have been separate tornadoes or simply an earlier part of the Jarrell tornado's evolution. An aerial survey conducted by the Birmingham, Alabama, office of the National Weather Service included the damage caused by the earlier F2 tornadoes—mostly to trees and roads—as part of the overall Jarrell tornado path. Some reports also include the F1 tornado near Prairie Dell as an earlier continuation of the Jarrell tornado. The final, unambiguous apparition of the Jarrell tornado began within the Williamson County line 3 miles (4.8 km) north of Jarrell as a narrow and rope-shaped funnel swathed in large amounts of dust when it touched down at 3:40 p.m. Like the two F3 tornadoes earlier in the day, it developed along the gust front produced by its parent thunderstorm. This mechanism is typical of tornadogenesis not associated with supercell thunderstorms. Traffic along Interstate 35 came to a stop as the tornado descended nearby. The Texas Highway Patrol also stopped traffic on both sides of the interstate under the expectation that the tornado would cross the highway; it ultimately moved parallel to Interstate 35. Tracking south-southwest, the tornado quickly intensified and grew to a 1⁄2 mile (0.80 km) in width, changing from its initial thin and white appearance to a blue and black color. F5 tornado damage was identified early in the tornado's path. Its intense winds scoured the ground and stripped pavement from roads. The tornado tore 525 feet (160 m) of asphalt as it crossed County Roads 308, 305, and 307; the thickness of the asphalt pavement was roughly 0.8 inches (20 mm). A culvert plant at the corner of Country Roads 305 and 307 collapsed. Nearby, a similar plant and a mobile home sustained some damage, with the latter struck by a 2×4 piece of lumber. The occupants of a mobile home 500 feet (150 m) north-northwest of the culvert plant fled to a frame house that the tornado later struck; the evacuees were killed while the mobile home sustained only minor damage. Some of the most extreme damage at this location was inflicted to a small metal-framed recycling plant that was obliterated, with little left of the structure besides a few twisted structural beams.

The tornado then slowly entered the Double Creek Estates subdivision where it exacted its most catastrophic impacts. Concurrently, the tornado expanded further to its maximum width of 3⁄4 mile (1.2 km). Eyewitnesses indicated that the tornado's movement slowed to around 5–10 mph (8.0–16.1 km/h) as it entered the neighborhood; this may have contributed to the resulting extreme destruction. The tornado destroyed the first home it encountered at the northwestern corner of the subdivision; a clock recovered from the remaining debris was stopped at 3:48 p.m., presumably marking the time the tornado entered the community. Much of the neighborhood was completely swept away with little debris remaining, with what was left being reduced to small and unrecognizable fragments that were dispersed over a wide area. The lack of large items that were recovered, and the granularity of the debris was indicative of the sheer strength of the tornado. Due to the tornado's slow movement, homes near the center of its path experienced tornadic winds for approximately three minutes. The mostly wooden-framed residences, some well-built and anchored, were completely obliterated and swept away, leaving behind concrete slab foundations swept clean of all debris. In some cases, parts of outbuilding and house foundations themselves in the subdivision were scoured away, and several were found missing all of their sill plates that connected the wood-frame homes to the foundations. Pieces of debris were found deposited in fields miles away from the subdivision, and extreme ground scouring occurred, reducing grassy fields into wide expanses of mud in the most severely affected areas. In some cases the ground was scoured out to a depth of 18 inches (46 cm). Vehicles in the neighborhood were tossed and mangled beyond recognition; at least six were found flattened in open areas and coated with mud and grass. Some were thrown as far as a 1⁄2 mile (0.80 km) away, and others were torn into multiple pieces of unrecognizable metal. Trees in the neighborhood were completely denuded and stripped entirely clean of all bark as well, including one that was found with an electrical cord impaled through the trunk.

All 27 fatalities associated with the Jarrell tornado occurred at Double Creek Estates, which at the time consisted of 131 residents living in 38 single-family homes and several mobile homes. Entire families were killed at Double Creek, including all five members of the Igo Family, all four members of the Moehring family, and all three members of the Smith family. Bodily remains were later found at 30 locations, and the physical trauma inflicted to some of the tornado victims was so extreme, that first responders reportedly had difficulty distinguishing human remains from the remains of animals at the site. Most of the deaths were attributed in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report to multiple trauma, though one death was attributed to asphyxia. The high intensity of the Jarrell tornado left those in its path with little recourse; most homes in Double Creek Estates were built on cement slab foundations and few had a basement or any form of storm shelter; nineteen people sought refuge in a single storm cellar. Some residents who followed prescribed safety measures nonetheless perished. One survivor holed up in a bathtub and was flung several hundred feet from her house onto a road. The walls of some homes along the periphery of the tornado path remained intact, protecting some of those who survived the tornado. Others chose to evacuate ahead of the approaching tornado. Forty structures were obliterated in Double Creek Estates. Three businesses adjacent to Double Creek Estates were also destroyed. In total, the tornado dealt $10–20 million in damage to the neighborhood. Around 300 cattle grazing in a nearby pasture were killed and some were found 0.25 miles (0.40 km) away. Hundreds of cattle were also dismembered and a few cows were also skinned by the tornado.

The tornado turned slightly towards the south-southwest after traversing Double Creek Estates. The damage in these outlying areas was somewhat scattershot; in one case, a mobile home suffered only minor damage while an adjacent house lost half of its roof. Metal buildings were unroofed along County Road 305 south of Jarrell. The road's guardrail was impaled by wooden planks thrown by the strong winds. The tornado then again crossed County Road 305 and entered a forest of cedar trees. Some of the damage to the trees suggested that the tornado may have been a multiple-vortex tornado, which was documented by Scott Beckwith, receiving a nickname as a “dead man walking”. Shortly after entering this forested area, the path of damage left behind by the tornado ended abruptly, with the National Centers for Environmental Information indicating that it lifted at 3:53 p.m. after remaining on the ground for 13 minutes and 5.1 miles (8.2 km). Other government accounts of the tornado list a total path length of 7.6 miles (12.2 km) after incorporating the preceding tornadoes north of Jarrell and near Prairie Dell. Between May 29 and June 1, the Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research carried out aerial and ground surveys of the tornadic damage in Texas in coordination with the Texas Wing Civil Air Patrol. The Jarrell tornado damage was classified as F5 severity throughout most of the tornado's path. However, a critique of the Fujita scale published by the National Institute of Standards and Technology suggested that winds between 158–206 mph (254–332 km/h), corresponding to an F3 rating on the scale, were sufficient to explain the damage wrought by the Jarrell tornado. The critique noted that some of the homes at Double Creek Estates, although built within the preceding 15 years, exhibited structural weaknesses in their design such as the lack of anchor bolts and steel straps in their foundations. Approximately $40 million in damage was inflicted upon property with another $100,000 inflicted upon crops. Twelve people were injured by the storm in addition to the twenty-seven killed.

Due to the unusual southwestward motion of the thunderstorm that caused the tornado, the sequence of weather events experienced by those affected was in the opposite order of typical tornadic events: the tornado arrived first, followed by the hail, wind, and rain of the parent thunderstorm. Despite the violence of the tornado and the presence of its associated mesocyclone aloft, the thunderstorm did not exhibit a distinct hook echo on weather radar typically associated with such tornadoes. This may have also been caused by the unusual southwestward motion of the thunderstorm, resulting in the tornado's placement in an atypical position relative to the thunderstorm's motion.

Non-tornadic effects

In addition to the tornadoes, there were 12 reports of large hail in Central Texas received by the National Weather Service during the late afternoon and evening. The largest hail—measuring nearly 4 in (100 mm) in diameter—was recorded in Cedar Park in conjunction with the F3 tornado that hit the city. Damaging hail was also reported in Georgetown beginning at 3:55 p.m. Severe thunderstorms also generated damaging straight-line winds across the Hill Country and South-Central Texas. Much of these winds were associated with the eventual, non-tornadic line of storms that resulted from the coalescence of the day's earlier storms. Wind gusts ranging between 58–71 mph (93–114 km/h) were recorded in Austin, with the peak 71 mph (114 km/h) wind gust occurring at Robert Mueller Municipal Airport at 4:20 p.m. There were also unofficial reports of winds reaching as high as 90 mph (140 km/h) to the west of Austin near Lake Travis. Kelly Air Force Base in San Antonio registered a gust of 122 mph (196 km/h) at 8:03 p.m. Gusts reached 61 mph (98 km/h) in Del Rio and overturned a plane at an airport near Seguin. The storms knocked out power to 60,000 electricity customers in Austin and as many as 21,000 electricity customers serviced by Texas Utilities. Telephone service for more than 3,000 residents in the Pedernales Valley was disrupted. The thunderstorms also produced heavy rain that triggered floods in Blanco, Gonzales, Karnes, and Travis counties. An official rainfall total of 1.44 in (37 mm) was documented in Austin, though 2.5 in (64 mm) of rain fell in nearby Round Rock. The rains caused Brushy Creek to flood beyond its banks as far east as Thorndale. One person drowned in floodwaters along Shoal Creek in Austin. Another person died in Cedar Park of cardiac arrest likely induced by storm-related stress. The Southwestern Insurance Information Service estimated that the totality of the storms' effects inflicted $25–40 million in insured losses; most insured claims originated from Cedar Park.

Aftermath

Law enforcement officers from the Texas Department of Public Safety, four municipal police departments, and two county sheriff's offices aided search-and-rescue efforts in the aftermath of the Jarrell tornado. The Texas National Guard and other volunteers from around Central Texas joined in the search. The Scott & White Blood Center facilitated blood donations. A temporary shelter was established by the American Red Cross at Jarrell High School for those displaced by the tornado, providing food and accepting clothes donations. The agency's relief operations, covering residents of 211 homes, cost an estimated $250,000; community donations covered at least $200,000 of the expenses. The Jarrell Volunteer Fire Department organized a temporary morgue; the deceased were later brought to the Travis County Forensic Center for identification. Although a death toll of 30 people was initially reported, that figure was later revised to 27; the inflated count was attributed to the dispersion of remains that led some fatalities to be tallied twice. Carcasses of livestock were buried at Double Creek Estates.

Texas Governor George W. Bush declared Williamson County a disaster area; Bush visited Jarrell on May 28 and described the tornadic damage as the worst he had ever witnessed. U.S. Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison also visited Jarrell and Cedar Park. Bush later requested federal aid for Williamson and Bell counties with support from Hutchinson. The Federal Emergency Management Agency elected not to provide federal aid, citing the contributions from private and state sources. Instead, the Small Business Administration and U.S. Department of Agriculture made available loans for the rebuilding of homes, farms, and ranches. The U.S. Congress approved a relief bill allocating $5.4 billion for 35 states affected by natural disasters, including Texas. However, the bill also included other provisions that led President Bill Clinton to veto the bill. A drive-through donation line was established at Auditorium Shores in Austin. Local musicians organized and performed at a benefit concert at Austin Music Hall, attracting an audience of 2,800 and raising about $94,000. Businesses also donated to the relief efforts.

First responders representing Cedar Park, Austin, Leander, Round Rock, and Williamson and Travis counties arrived in Cedar Park shortly after the city was hit by a tornado. Texas A&M University supplied equipment for search-and-rescue operations in the aftermath of the Cedar Park tornado. These operations were the first test of the 186-member Texas Urban Search and Rescue Team, which was created following the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. Vouchers were distributed by the American Red Cross to storm victims in the Buttercup Creek subdivision for clothing, food, and other supplies. Texas State Troopers blocked areas of Buttercup Creek to prevent looting.

A memorial was erected in downtown Jarrell bearing the names of the 27 people killed by the Jarrell tornado. The Jarrell Memorial Park was established near Double Creek Estates on the land of the former Igo family, who perished in the tornado. The park contains 27 trees planted in honor of the victims. In 2019, the memorial was relocated to the park along with the city's historical marker. The events and survivor accounts of the tornado were profiled in television documentaries such as the 1999 episode of HBO's America Undercover series titled "Fatal Twisters: A Season of Fury", the 1999 BBC television series titled Twister Week (also known as Tornado Diary in the United States) in an episode titled "Tornado Alley", the seventh episode of the Discovery Channel program Storm Warning, produced by GRB Entertainment, and the 2006 documentary Ultimate Disaster (also known as Mega Disaster) on National Geographic Channel.

See also

- List of North American tornadoes and tornado outbreaks

- 1922 Austin twin tornadoes – also featured southwestward-tracking tornadoes that struck the Austin, Texas, area

- Tornado outbreak of April 6–9, 1998 – produced the official first F5 tornado after the Jarrell tornado

- 1953 Waco tornado – the deadliest tornado in Texas history

Notes

- ^ All times in Central Daylight Time (UTC-5:00) unless otherwise noted.

- ^ All damage totals are in 1997 USD unless otherwise noted.

- The divergence of air at the upper-levels of the troposphere promotes upward motion and aids thunderstorm development.

- Wind shear—a change of wind velocities with height—is necessary to produce rotating thunderstorms, making it a key physical condition for the development of tornadoes.

- Environments with thunderstorms often exhibit CAPE exceeding 1,000 J/kg, with extreme cases exhibiting CAPE greater than 5,000 J/kg.

- All dates are based on Central Daylight Time (UTC-05:00); however, all times are in Coordinated Universal Time for consistency.

- These winds would correspond to an EF3–EF5 tornado on the modern Enhanced Fujita Scale. The critique noted that the winds corresponding to an F3 tornado in the Fujita scale would completely destroy most homes.

References

- ^ "Storm Data" (PDF). Storm Data. 39 (5). Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center. May 1997. ISSN 0039-1972. Retrieved April 7, 2021 – via National Centers for Environmental Information.

- ^ Paz, Enrique; Kolavic, Shellie; Zane, David (November 14, 1997). "Tornado Disaster – Texas, May 1997". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 46 (45). Centers for Disease Control. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ Corfidi, Stephen F. (July 1998). Some Thoughts On the Role Mesoscale Features Played in the 27 May 1997 Central Texas Tornado Outbreak. 19th Severe Local Storms Conference. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Storm Prediction Center. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Henderson et al. (1998), p. 1.

- Morgan et al. (1998), p. 4.

- "Divergence". National Weather Service Glossary. National Weather Service. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- "Mapping May's Tornado Outbreak: Ingredients for the Perfect Storm". National Environmental Satellite Data and Information Service. June 20, 2019. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- "Tornadoes - Nature's Most Violent Storms". About Tornadoes. Peachtree City, Georgia: National Weather Service. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ Morgan et al. (1998), p. 3.

- ^ Morgan et al. (1998), p. 1.

- ^ Henderson et al. (1998), p. 2.

- Houston and Wilhelmson (2007a), p. 724.

- Houston and Wilhelmson (2007a), p. 702.

- ^ "May 1997 Tornado Outbreak" (PDF). New Braunfels, Texas: National Weather Service. May 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- Houston and Wilhelmson (2007a), pp. 704–711.

- Houston and Wilhelmson (2007a), p. 701.

- Houston and Wilhelmson (2007a), p. 723.

- ^ Toohey, Marty (September 25, 2018). "Power and devastation of the Jarrell tornado, by the numbers". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas: Gannett. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- Houston and Wilhelmson (2007a), pp. 724–725.

- Morgan et al. (1998), p. 14.

- Davies, Jonathan M. (August 16, 2002). Significant Tornadoes in Environments with Relatively Weak Shear (PDF). 21st Conference on Severe Local Storms. American Meteorological Society. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- Morgan et al. (1998), pp. 4–5.

- ^ Houston and Wilhelmson (2007a), p. 715.

- Houston and Wilhelmson (2007a), p. 713.

- ^ Houston and Wilhelmson (2007b), p. 729.

- Houston and Wilhelmson (2007b), p. 730.

- ^ "The Tornadoes of May 27, 1997". Jarrell-Tornado-Anniversary. Fort Worth, Texas: National Weather Service Fort Worth/Dallas, TX. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Henderson et al. (1998), p. 3.

- ^ Henderson et al. (1998), p. 15.

- ^ Morgan et al. (1998), pp. 12–13.

- Henderson et al. (1998), p. 5.

- "SPC Day 1 Convective Outlook Issued at 0603Z May 27 1997". Norman, Oklahoma: Storm Prediction Center. May 27, 1997. Retrieved April 7, 2021 – via Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies.

- ^ Henderson et al. (1998), pp. 5–10.

- Henderson et al. (1998), pp. 11–12.

- Texas Event Report: F0 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- Texas Event Report: F0 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- Texas Event Report: F3 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- Texas Event Report: F3 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Peters, Brian E. (1998). "Aerial Damage Survey of the Central Texas Tornadoes of May 27, 1997" (PDF). National Weather Service. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- Texas Event Report: F0 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- Texas Event Report: F3 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Texas Event Report: F1 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- Texas Event Report: F1 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Texas Event Report: F2 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Texas Event Report: F2 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- Texas Event Report: F1 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Texas Event Report: F5 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- Texas Event Report: F0 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- Texas Event Report: F3 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- Texas Event Report: F3 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Dworin, Diana; Easterly, Greg (May 30, 1997). "Cedar Park residents ready to rebuild". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. pp. A8. Retrieved April 10, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Henderson et al. (1998), p. 4.

- Dworin, Diana (May 29, 1997). "Tornado's oddities emerge in the rubble". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. Retrieved April 10, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Texas Event Report: F1 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- Texas Event Report: F4 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Jayson, Sharon (May 31, 1997). "In Pedernales Valley, tragedy is smaller — but equally felt". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. pp. A1, A11. Retrieved April 10, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Texas Event Report: F1 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- Texas Event Report: F0 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- Texas Event Report: F0 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- Texas Event Report: F0 Tornado. Storm Events Database (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- Graves, Eric. "Facebook". www.facebook.com. Retrieved July 3, 2024.

- Sauers, Camille (March 23, 2022). "Revisiting the 1997 Jarrell tornado, one of the deadliest in Texas history". www.mysanantonio.com.

- Vertuno, Jim (May 24, 2002). "Five years later, town still coping with deadly '97 tornado". Plainview Herald.

- "Sheriff's deputy describing the devastation at a Jarrell, Texas, subdivision leveled by a tornado". www.sfgate.com. May 28, 1997.

- ^ Harmon, Dave (May 28, 1997). "'Like a war zone'". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. pp. A1, A12. Retrieved April 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Beach, Patrick (May 29, 1997). "Jarrell's toll 27; 23 still missing". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. pp. A1, A21. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ Osborn, Claire; Easterly, Greg; Ward, Pamela (May 28, 1997). "Nearly destroyed in '89, Jarrell is slammed again". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. pp. A1, A10. Retrieved April 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Monroe, Nichole (May 28, 1997). "1989 tornado punished Jarrell with fatal force". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. p. A10. Retrieved April 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kelso, John (May 29, 1997). "Upheaval roars after winds leave". Austin American-Statesman. pp. A1, A19. Retrieved April 10, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Tornadoes kill 30 in Central Texas". El Paso Times. El Paso, Texas. Associated Press. May 28, 1997. p. 1A. Retrieved April 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Henderson et al. (1998), p. A9.

- Stanley, Dick (May 29, 1997). "Storm's fury overwhelmed warnings". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. p. A18. Retrieved April 10, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Houston and Wilhelmson (2007b), p. 1.

- Miller, Daniel J.; Doswell, Charles A. III; Brooks, Harold E.; Stumpf, Gregory J.; Rasmussen, Erik. "Highway Overpasses as Tornado Shelters: Fallout From the 3 May 1999 Oklahoma/Kansas Violent Tornado Outbreak". Norman, Oklahoma: National Weather Service Norman, OK. p. 17. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- Phan and Simiu (1998), p. 8.

- ^ Phan and Simiu (1998), p. 9.

- Schuman, Shawn (November 23, 2023). "May 27, 1997 — The Jarrell, Texas Tornado". stormstalker.wordpress.com. Wordpress. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- Henson, Bob (May 26, 2016). "Twenty Years On: A Look Back at the Jarrell Tornado Catastrophe". Weather Underground. TWC Product and Technology. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ Verhovek, Sam Howe (May 29, 1997). "Little Is Left in Wake of Savage Tornado". The New York Times. New York. p. A1. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ Phan and Simiu (1998), p. 12.

- Schuman, Shawn (November 23, 2023). "May 27, 1997 — The Jarrell, Texas Tornado". stormstalker.wordpress.com. Wordpress. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ "The Jarrell, TX Tornado of 27 May 97". Norman, Oklahoma: Storm Prediction Center. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- Schuman, Shawn (November 23, 2023). "May 27, 1997 — The Jarrell, Texas Tornado". stormstalker.wordpress.com. Wordpress. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ Beach, Patrick (June 1, 1997). "Their roots held". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. pp. A1, A20 – A21. Retrieved April 10, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Rucker, Hanna (May 25, 2022). "Three families killed in the 1997 Jarrell tornado are buried together in Georgetown". kvue.com. KVUE. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ Todd, Mike (May 29, 1997). "In hunt for bodies, official finds nature's brutality". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. p. A18. Retrieved April 10, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Schuman, Shawn (November 23, 2023). "May 27, 1997 — The Jarrell, Texas Tornado". stormstalker.wordpress.com. Wordpress. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ Henderson et al. (1998), p. 12.

- ^ Henderson et al. (1998), p. 11.

- Phan and Simiu (1998), p. 13.

- NWS Austin/San Antonio, TX; NWS Fort Worth/Dallas, TX (May 19, 2022). "May 27, 1997 Central Texas Tornado Outbreak". ArcGIS StoryMaps. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- "The TIME Vault: June 9, 1997". Time. Retrieved June 29, 2023.

- Edge, The Professor On (June 14, 2020). "(A preview of) Meteorology and Myth Part VII: "The Dead Man Walking"". From Equatorial Icecaps to Polar Deserts. Retrieved June 29, 2023.

- Phan and Simiu (1998), p. 2.

- "Enhanced F Scale for Tornado Damage". Norman, Oklahoma: Storm Prediction Center. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- Phan and Simiu (1998), p. 16.

- ^ Stanley, Dick (May 28, 1997). "Cool air, hot air don't mix quietly". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. p. A13. Retrieved April 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Insurers lower storm estimate by $60 million". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. May 31, 1997. p. A11. Retrieved April 10, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Moscoso, Eunice (May 31, 1997). "Donations covering Red Cross costs". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. p. A10. Retrieved April 10, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Easterly, Greg (May 31, 1997). "Federal aid is requested for residents". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. p. A12. Retrieved April 10, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Rivera, Dylan (June 7, 1997). "Jarrell won't get federal relief". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. pp. A1, A8. Retrieved April 10, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Congress sends disaster bill toward likely veto by Clinton". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. June 6, 1997. p. A2. Retrieved April 10, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hopper, Leigh (May 30, 1997). "A torn town finds it has thousands of giving neighbors". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. pp. A1, A7. Retrieved April 10, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Riemenschneider, Chris (June 6, 1997). "Benefit raises $94,000 for victims". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. p. B1. Retrieved April 10, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Riemenschneider, Chris (May 31, 1997). "Texas bands will play Tornado Jam benefit". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. p. A11. Retrieved April 10, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Trower, Tara; Lindell, Chuck (May 29, 1997). "Search continues at Albertson's". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. p. A20. Retrieved April 10, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Historical Marker: Jarrell". Williamson County Historical Commission. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- Windler, Chikage (May 26, 2017). "Jarrell marks 20 years since tornado that killed 27". CBS Austin. Austin, Texas. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- "'FATAL TWISTERS' ISN'T ABOUT STORMS, IT'S ABOUT PAIN". Orlando Sentinel. July 11, 1999. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- "Fatal Twisters: A Season of Fury". America Undercover. July 12, 1999. HBO. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved September 28, 2021 – via YouTube.

- "Tornado Alley". Twister Week. 1999. BBC One. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- Storm Warning - Episode 7 - Jarrell, Texas Twister/Ice Queen/Brazil Flood. GRB Entertainment. 1997. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved January 8, 2021 – via YouTube.

- Mega Disaster: Tornado. Natural History New Zealand/National Geographic Channel. 2006. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved January 8, 2021 – via YouTube.

Bibliography

- Henderson, James H.; Hakkarinen, Ida M.; Lerner, William H.; McLaughlin, Melvin R.; Looney, James M.; McIntyre, E. L.; Peters, Brian E.; Trainor, Marilu; Paz, Enrique; Kolavic, Shellie Ann; Zane, David; Phan, Long T. (April 1998). The Central Texas Tornadoes of May 27, 1997 (PDF) (Service Assessment). Silver Spring, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- Houston, Adam L.; Wilhelmson, Robert B. (March 1, 2007). "Observational Analysis of the 27 May 1997 Central Texas Tornadic Event. Part I: Prestorm Environment and Storm Maintenance/Propagation". Monthly Weather Review. 135 (3). American Meteorological Society: 701–726. Bibcode:2007MWRv..135..701H. doi:10.1175/MWR3300.1.

- Houston, Adam L.; Wilhelmson, Robert B. (March 1, 2007). "Observational Analysis of the 27 May 1997 Central Texas Tornadic Event. Part II: Tornadoes". Monthly Weather Review. 135 (3). American Meteorological Society: 727–735. Bibcode:2007MWRv..135..727H. doi:10.1175/MWR3301.1.

- Morgan, Carl; Orrock, Jeff; Rydell, Nezette; Ward, Jimmy (July 1998). "A Meteorological and Radar Analysis of the Central Texas Tornado Outbreak on May 27, 1997" (PDF). New Braunfels, Texas: National Weather Service. Retrieved April 6, 2021 – via NOAA Institutional Repository.

- Phan, Long T.; Simiu, Emil (July 1998). The Fujita Tornado Intensity Scale: A Critique Based on Observations of the Jarrell Tornado of May 27, 1997 (PDF). Gaithersburg, Maryland: National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

External links

- Aerial Damage Survey of the Central Texas Tornadoes of May 27, 1997 (PDF) (National Weather Service), includes discussion and map of the tornado's track

- Texas Tornadoes (National Climatic Data Center)

- Satellite imagery (University of Wisconsin–Madison)

- Stormtrack Magazine Nov/Dec 1997: Jarrell, Texas Tornado Expanded Edition (PDF)

| Tornado outbreaks of 1997 | |

|---|---|