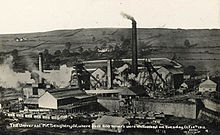

The coal industry in Wales played an important role in the Industrial Revolution in Wales. Coal mining in Wales expanded in the 18th century to provide fuel for the blast furnaces of the iron and copper industries that were expanding in southern Wales. The industry had reached large proportions by the end of that century, and then further expanded to supply steam-coal for the steam vessels that were beginning to trade around the world. The Cardiff Coal Exchange set the world price for steam-coal and Cardiff became a major coal-exporting port. The South Wales Coalfield was at its peak in 1913 and was one of the largest coalfields in the world. It remained the largest coalfield in Britain until 1925. The supply of coal dwindled, and pits closed in spite of a UK-wide strike against closures. Aberpergwm Colliery is the last deep mine in Wales.

The South Wales Coalfield was not the only coal mining area of the country. There was a sizeable industry in Flintshire and Denbighshire in northeast Wales, and coal was also mined in Anglesey.

Coal mining areas

The South Wales Coalfield extends from parts of Pembrokeshire and Carmarthenshire in the west, through Swansea, Llanelli, Neath Port Talbot, Bridgend County Borough, Rhondda Cynon Taf, Merthyr Tydfil, Caerphilly County Borough and Blaenau Gwent to Torfaen in the east. The rocks in this area were laid down in late Carboniferous times. At that time warm seas invaded much of southern and northeastern Wales, and coral reefs flourished and were laid down as limestone deposits. In South Wales particularly, extensive swamps developed where tree-sized clubmosses and ferns grew. The decay of this vegetation as it died formed peat, which was slowly buried under other sediments. The peat was slowly consolidated and converted by the pressure of overlying layers into seams of coal. Although thinner than the original peat layers, some of the coal deposits in South Wales are of great thickness.

The North Wales Coalfield is divided into two parts: the Flintshire Coalfield to the north and the nearly contiguous Denbighshire Coalfield to the south. The Flintshire Coalfield extends from the Point of Ayr in the north, through Connah's Quay to Caergwrle in the south. It also extends under the Dee Estuary to the Neston area of the Wirral Peninsula. The Denbighshire Coalfield extends from near Caergwrle in the north, to Wrexham, Ruabon, Rhosllannerchrugog and Chirk in the south, a small part extending into Shropshire in the Oswestry area.

History

Ancient times

Coal is the most abundant fossil fuel in the Earth's crust and has a long history of being exploited. Archaeological evidence shows that it was burned in funeral pyres in Wales during the Bronze Age and cinders have been found in Roman settlements in Britain. Originally the coal would have come from outcropping coal seams, and from lumps of sea coal gathered from the foreshore.

North Wales

In north Wales, the Flintshire manors of Ewloe, Hopedale, and Mostyn and the Denbighshire manor of Brymbo were reported to be making profits from trading coal during the 14th and 15th centuries. By 1593, coal was being exported from ports on the Dee Estuary. The trade developed swiftly, and by 1616 the principal collieries were at Bagillt, Englefield, Leaderbrook, Mostyn, Uphfytton and Wepre. Most mines were horizontal adits or shallow bell pits, though a few were becoming large enough to have accumulations of water and ventilation problems.

South Wales

By the 17th century, coal was being dug from shallow deposits for local use, and by the beginning of the 18th century a trade in coal was developing along the coast from such areas as Pembrokeshire, Llanelli and Swansea Bay. As surface deposits were exhausted by opencast mining, shallow pits were dug, and later bell pits, with more coal being extracted from short galleries. Soon, horizontal shafts were being dug into the hillsides and barrows manoeuvred along wooden tracks.

During the Industrial Revolution, Wales was at the forefront of the development of new technologies for the mining industry. These innovations included the use of water power for winding gear, the provision of mine ventilation, the use of steam engines for both winding and pumping and the use of underground tramways and canals for transport. Welsh mine-owners pioneered the use of horse-drawn and later steam railways to transport coal to the docks. The switch from wood to coal for fuel during the Industrial Revolution was heavily influenced by Welsh innovations.

The land under which coal could be found was generally in private ownership. John Crichton-Stuart, 2nd Marquess of Bute was a large landowner in south Wales and developed the coal and iron industries in Glamorganshire in the 19th century. Agriculture ceased to be the main source of employment in the county as mining and other industries came to the fore, and he transformed his South Wales estates into a major industrial enterprise. He commissioned surveys in 1817 and again in 1823 to 1824 which showed huge reserves of coal under his land. He sold some outlying parts of his estate in order to purchase other potentially more productive areas, and claimed rights to minerals under certain common lands through his feudal titles.

Lord Bute was one of the main forces behind the development of Cardiff Docks for the export of coal and iron from south Wales. By 1840, the network of canals and railways enabled 4.5 million tons of coal to be mined and transported. Of this, about half was used by the steel industry, about 750,000 tons went for export, and the rest was put to other industrial and domestic use. By 1854, coal production had nearly doubled, and 2.5 million tons was being exported

See also

References

- ^ Hughes, Stephen R. (1994). Collieries of Wales: Engineering and Architecture. Aberystwyth: Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-1-871184-11-2.

- "Coal: Aberpergwm colliery gets OK to mine 40 million tonnes". BBC News. 26 January 2022.

- "South Wales (geological map)". Geological Maps of Selected British Regions. Southampton University. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- "Environmental Change and Mineral Formation in Wales". Wales Underground. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ^ The North Wales Coalfield, Coalmining History Research Centre, 1953, archived from the original on 4 March 2016, retrieved 7 April 2016

- British Geological Survey, 2007 Bedrock Geology: UK South, 1:625,000 scale geological map (5th edn), BGS, Keyworth, Notts

- Ramani, Raja Venkat. "Coal mining". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- "The growth and development of settlement and population in Flintshire, 1801–1851". Flintshire Historical Society Publications. 25. 1971–1972.

- Davies, John (1981). Cardiff and the Marquesses of Bute. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 9780708324639.

- "Industry: 19th century coal mining". BBC Wales. 15 August 2008. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

| Geography of Wales | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | |||||||

| Environment | |||||||

| Land use | |||||||

| Administrative |

| ||||||

| Social | |||||||

| Other | |||||||

| Wales articles | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History | |||||||||||||||||

| Geography | |||||||||||||||||

| Politics |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Economy | |||||||||||||||||

| Society |

| ||||||||||||||||