The Code Girls or World War II Code Girls is a nickname for the more than 10,000 women who served as cryptographers (code makers) and cryptanalysts (code breakers) for the United States Military during World War II, working in secrecy to break German and Japanese codes.

These women were a crucial part of the war and broke numerous codes that were of significant importance to the Allied Forces and helped them to win and shorten the Second World War.

Recruitment

In the months prior to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States Military began to recruit women to work for their various branches, as the men who previously occupied these positions were deployed overseas to fight in the war.

Many of the recruited women were hired to work as cryptographers and cryptanalysts by the United States Navy. These women had to be native to the United States, as to make sure that they had no ties to foreign countries. The government sought after young females who pioneered the STEM field and excelled in mathematics and world languages—often young college students and teachers with a driving motivation. After the attack, the Navy's recruitment activities and advertisements increased dramatically as the United States' joined the Allied Forces to fight Axis powers during World War II.

During the recruitment process, the women were asked if they liked crossword puzzles and if they were engaged or wanted to be married. Those who answered 'yes' and 'no', respectively, were moved forward in the hiring process. The military were looking for women that were willing to relocate and had little to no ties to their current lifestyle. Candidates were invited to secret meetings where they were offered the opportunity to take a code-breaking training course and were sworn to secrecy- exposing their work was considered treason and could have been punishable by death. Those who passed the course were invited to Washington, D.C. after college graduation to join the Navy as civilian employees.

The Army also began recruiting women code breakers around this time. Army officials met with representatives from women's colleges at the Mayflower Hotel in hopes of recruiting their top students before the Navy was able to do so, and in May of 1942, the female civilian code breakers, were accepted into the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps, and thus into Military Service .

Due to the nature of secrecy of the female code-breakers of World War II and the "loose lips sink ships" propaganda and mentality during that time, a significant amount of their work and recruitment process remains a mystery, and without an existing record of a roster of all of the Code Girls, it is almost impossible to track down all of these individuals and get all of the details of their recruitment experience.

Code-breaking

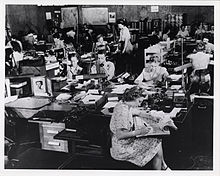

The code girls worked in many branches of the armed services, including: U.S. Army, U.S. Navy, U.S. Coastguard, U.S. Air Force, U.S. Marine Corps, etc. The first recruits reported to Navy headquarters in Washington, D.C. which quickly became crowded. Nearly 10,000 women were recruited from across the country to work. By 1943, the Navy expanded its operations by commandeering the original location of Mount Vernon College for Women for use as the Naval Communications Annex.

The Army also quickly outgrew its Washington, D.C. office and added a second location at Arlington Hall Junior College for Women. By 1945, 70 percent of the Army's code-breaking team was female.

Among their duties, the women operated code-breaking machines, analyzed and broke enemy codes, built libraries of resources on enemy operations, intercepted radio signals, and tested the security of American codes. During their preparation, code girls were trained by the government in top-secret coding classes. In these classes, women learned cryptography, making codes, and cryptanalysis, breaking codes. The work they did in the Navy was highly classified—the punishment for sharing their work being punishable by death.

During each month of 1944, code breakers intercepted about 30,000 Japanese Navy water-transport messages which led to the sinking of nearly all Japanese supply ships heading to the Philippines or South Pacific. Prior to D-Day, they shared false information and radio messages to intentionally mislead the Germans about the Allied Forces' landing location.

A major accomplishment by female cryptographers was breaking the Purple Cipher. An intricate and improved version of the German Enigma Machine was created by the Japanese government—dubbed the "Purple" Enigma. The complexity of this machine was revolutionary, but code girl, Genevieve Grotjan, along with her team broke the Japanese codes. The result of their work allowed the U.S. naval forces to plan and execute the Battle of Midway, ultimately changing the course of the Pacific Theater of World War II.

When asked publicly about their highly sensitive work, the women were told to reply that they 'sharpened pencils and emptied wastebaskets'. Reportedly, their cover story was never challenged.

Gender Inequality

Female cryptographers in World War II faced many discriminatory challenges in the work force. These recruited women acquiring adept skills in math, science, and foreign languages, were to remain dutiful and patriotic with no expectation of public credit for their concealed intelligence work. Many people (mainly men) considered women better suited for code-breaking work. Inferring the oppressive belief that women were greater equipped for dull work and thus assigned work requiring close attention to details rather than challenging genius commissions. That was considered men's work at the time. Due to these injustices women struck back, but this led to the public believing women were gossipers and complainers. However society believed women were also less problematic with drinking and bragging. In terms of sexual behavior, women were seen less of a security risk than men.

In public, the women were authorized to keep their jobs confidential, and substitute their work as secretaries or did menial jobs, completing tasks such as sharpening pencils and taking out the trash. If a stranger were to show suspicious interest about their work, some groups would use certain signals in bars to alert the other women. For example if a group member ordered a Vodka Collins then the Code Girls knew to dismiss themselves to the restroom and flee the area. Other women improvised their answers and strategically sat on the laps of commanding officers and soldiers. As young American women it was effortless to convince curious strangers that they did menial work or existed only as a plaything for the men they worked with.

For more than 70 years women in this generation did not expect nor receive recognition for achievement in public life. Their efforts were completely hidden and only mentioned in passing, with no historical record, interviews, or first-person memoirs afterwards. Now their story is being told in various sources such as the articles and books of Liza Mundy, “including the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, and other archival repositories along with declassification requests and interviews with living code breakers” Years later some Code Girls feel reluctant to reveal certain information outside of the Code-breaking compound.

After World War II

The Code Girls of World War II laid out important foundations and pioneered the work that would become part of modern-day cybersecurity and communication agencies. They created pathways to clandestine eavesdropping operations, and after the end of the war, the Navy and Army secret cryptography operations were merged to create what it is now known as the National Security Agency.

Many of the women were kicked out of the Military and pushed out of the technological workforce after the war ended, as the deployed soldiers returned from war and settled back into their previous jobs- with only a few continuing to work for the National Security agency and other roles within the military. These women were all sworn to secrecy and their work and contributions went silent for years, which led to many of their accomplishments to be forgotten or claimed by their male counterparts.

Impact and accomplishments

Additionally to the Army’s code breaking operation, there was an African American group unit (implemented by Eleanor Roosevelt) that helped with the enciphered communications of certain companies, and to get better insight of who was collaborating with dictators such as Mitsubishi and Hitler. Women such as Agnes Meyer Driscoll, aided in unraveling the Japanese navy fleet codes during the 1920s and 1930s.

Another significant cryptanalyst named Elizabeth Smith Friedman was the first to discover the US government’s codebreaking bureau in 1916, where she worked for Riverbank at an unconventional Illinois estate. During prohibition, she deciphered the codes of which businesses were smuggling alcoholic beverages, also known as rum running. In September 1940, due to Genevieve Grotjan’s key expertise, the Allies were able to get information on the Japanese diplomats’ communications throughout World War II. Her decrypting assisted in monitoring the enciphering machines used by Hiroshi Oshima, Japanese Ambassador to Nazi Germany, who was close to Adolf Hitler and other Nazi political and military leaders. He got much detailed information from the Nazis, and was given access to their military installations - which he transmitted to Japan, not realizing that the Americans were reading his transmissions which were a major source of information.

The navy and army were all competing for the women’s skills after recognizing all of their efforts made in the World War. Specifically, Ada Comstock urged for the Navy to train the undergraduates in cryptanalysis, realizing how the country lacked a demand of educated women after the surprise attack at Pearl Harbor. More women were being enlisted in the workforce, especially to the WAAC recruiting station, where they needed to pass background checks to be in the code breaking service. At Arlington Hall (which became the headquarters of the United States Army Signal Intelligence Service), Ann Caracristi went against master Japanese cryptanalysts and solved many message addresses which helped the military intelligence locate many of the Japanese troops. Japanese ships were sunk as a result of the messages given to Dot Braden and other women who deciphered naval codes along the major oceans.

The Japanese fleet code called JN-25 was used by these women who created the cryptoanalytic assembly line, and aided in shooting down Isoroku Yamamoto's plane. All of the machines that targeted and attacked the German Enigma ciphers were managed by women, additionally they tracked the locations of Allied convoys and U-boats. In order to destroy the German naval Enigma ciphers, women assisted in building one hundred "bombe" machines in a classified building located in the National Cash Register Company. JAH, which was an all purpose code that contained important material such as speeches, orders and memos was handled by Virginia Dare Aderholdt. She was able to know when Japan evacuated from southern China and track all of Naotake Sato's endeavors.

Notable WW II era women cryptologists

Notable women who contributed to the U.S. cryptologic effort during the World War II era include:

- Virginia Dare Aderholdt – decrypted the Japanese surrender message

- Ann Z. Caracristi – later became deputy director of the National Security Agency, its highest civilian leadership position

- Margaret Crosby – worked as a cryptographer for the OSS' Greek Desk

- Agnes Meyer Driscoll – broke the Japanese M-1 cipher machine

- Genevieve Grotjan Feinstein – found the crucial break in the Japanese Purple cipher

- Elizebeth Smith Friedman – helped convict rum runners during Prohibition and thwarted Nazi agents in South America in WW II

- Helen Nibouar – helped develop the SIGABA cipher machine

- Joan Clarke – helped break the Enigma code along with Alan Turing.

References

- ^ "World War II Code Girls: What's in a Name?". National Archives. March 20, 2020. Retrieved November 19, 2022.

- ^ Mundy, Liza (2017). Code girls : the untold story of the American women code breakers of World War II. New York. ISBN 978-0-316-35253-6. OCLC 972386321.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Interview with Liza Mundy". The National WWII Museum | New Orleans. February 29, 2020. Retrieved November 8, 2022.

- ^ "She was a World War II Codebreaker | Arts & Sciences". www.bu.edu. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ Mundy, Liza (October 10, 2017). "The Secret History of the Female Code Breakers Who Helped Defeat the Nazis". POLITICO Magazine. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- Taylor, Lisa (February 26, 2018). "Sharpened Pencils and Sharper Minds: World War II Women Code Breakers | Folklife Today". blogs.loc.gov. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- Showalter, Elaine (October 6, 2017). "The brilliance of the women code breakers of World War II". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Today in Security History: Breaking the Purple Cipher". www.asisonline.org. Retrieved November 19, 2022.

- Magazine, Smithsonian; Wei-Haas, Maya. "How the American Women Codebreakers of WWII Helped Win the War". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

External links

- World War II Code Girls: What’s in a Name? - National Archives

- Interview, Navy cryptographer - Frances Lynd Scott Collection, (AFC/2001/001/48208), Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress

- Interview, Army cryptographer - E. Jean P. Perdue Brownlee Collection, (AFC/2001/001/09220), Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress

- "Code Girls" Reunion, Library of Congress