| This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (December 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In constraint satisfaction, local consistency conditions are properties of constraint satisfaction problems related to the consistency of subsets of variables or constraints. They can be used to reduce the search space and make the problem easier to solve. Various kinds of local consistency conditions are leveraged, including node consistency, arc consistency, and path consistency.

Every local consistency condition can be enforced by a transformation that changes the problem without changing its solutions; such a transformation is called constraint propagation. Constraint propagation works by reducing domains of variables, strengthening constraints, or creating new constraints. This leads to a reduction of the search space, making the problem easier to solve by some algorithms. Constraint propagation can also be used as an unsatisfiability checker, incomplete in general but complete in some particular cases.

Local consistency conditions can be grouped into various classes. The original local consistency conditions require that every consistent partial assignment (of a particular kind) can be consistently extended to another variable. Directional consistency only requires this condition to be satisfied when the other variable is greater than the ones in the assignment, according to a given order. Relational consistency includes extensions to more than one variable, but this extension is only required to satisfy a given constraint or set of constraints.

Assumptions

In this article, a constraint satisfaction problem is defined as a set of variables, a set of domains, and a set of constraints. Variables and domains are associated: the domain of a variable contains all values the variable can take. A constraint is composed of a sequence of variables, called its scope, and a set of their evaluations, which are the evaluations satisfying the constraint.

The constraint satisfaction problems referred to in this article are assumed to be in a special form. A problem is in normalized form, respectively regular form, if every sequence of variables is the scope of at most one constraint or exactly one constraint. The assumption of regularity done only for binary constraints leads to the standardized form. These conditions can always be enforced by combining all constraints over a sequence of variables into a single one and/or adding a constraint that is satisfied by all values of a sequence of variables.

In the figures used in this article, the lack of links between two variables indicate that either no constraint or a constraint satisfied by all values exists between these two variables.

Local consistency

The "standard" local consistency conditions all require that all consistent partial evaluations can be extended to another variable in such a way that the resulting assignment is consistent. A partial evaluation is consistent if it satisfies all constraints whose scope is a subset of the assigned variables.

Node consistency

Node consistency requires that every unary constraint on a variable is satisfied by all values in the domain of the variable, and vice versa. This condition can be trivially enforced by reducing the domain of each variable to the values that satisfy all unary constraints on that variable. As a result, unary constraints can be neglected and assumed incorporated into the domains.

For example, given a variable with a domain of and a constraint , node consistency would restrict the domain to and the constraint could then be discarded. This pre-processing step simplifies later stages.

Arc consistency

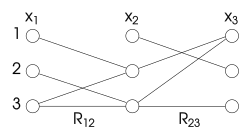

A variable of a constraint satisfaction problem is arc consistent with another one if each of its admissible values are consistent with some admissible value of the second variable. Formally, a variable is arc consistent with another variable if, for every value in the domain of there exists a value in the domain of such that satisfies the binary constraint between and . A problem is arc consistent if every variable is arc consistent with every other one.

For example, consider the constraint where the variables range over the domain 1 to 3. Because can never be 3, there is no arc from 3 to a value in so it is safe to remove. Likewise, can never be 1, so there is no arc, therefore it can be removed.

Arc consistency can also be defined relative to a specific binary constraint: a binary constraint is arc consistent if every value of one variable has a value of the second variable such that they satisfy the constraint. This definition of arc consistency is similar to the above, but is given specific to a constraint. This difference is especially relevant for non-normalized problems, where the above definition would consider all constraints between two variables while this one considers only a specific one.

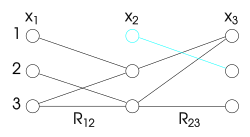

If a variable is not arc consistent with another one, it can be made so by removing some values from its domain. This is the form of constraint propagation that enforces arc consistency: it removes, from the domain of the variable, every value that does not correspond to a value of the other variable. This transformation maintains the problem solutions, as the removed values are in no solution anyway.

Constraint propagation can make the whole problem arc consistent by repeating this removal for all pairs of variables. This process might have to consider a given pair of variables more than once. Indeed, removing values from the domain of a variable may cause other variables to become no longer arc consistent with it. For example, if is arc consistent with but the algorithm reduces the domain of , arc consistency of with does not hold any longer, and has to be enforced again.

A simplistic algorithm would cycle over the pairs of variables, enforcing arc consistency, repeating the cycle until no domains change for a whole cycle. The AC-3 algorithm improves over this algorithm by ignoring constraints that have not been modified since they were last analyzed. In particular, it works on a set of constraints that initially contains all constraints; at each step, it takes a constraint and enforces arc consistency; if this operation may have produced a violation of arc consistency over another constraint, it places that constraint back in the set of constraints to analyze. This way, once arc consistency is enforced on a constraint, this constraint is not considered again unless the domain of one of its variables is changed.

Path consistency (k-consistency)

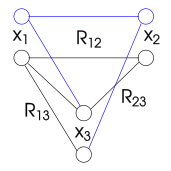

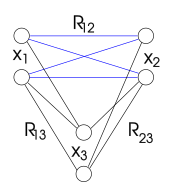

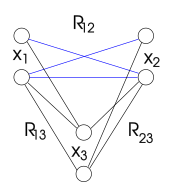

Path consistency is a property similar to arc consistency, but considers pairs of variables instead of only one. A pair of variables is path-consistent with a third variable if each consistent evaluation of the pair can be extended to the other variable in such a way that all binary constraints are satisfied. Formally, and are path consistent with if, for every pair of values that satisfies the binary constraint between and , there exists a value in the domain of such that and satisfy the constraint between and and between and , respectively.

The form of constraint propagation that enforces path consistency works by removing some satisfying assignment from a constraint. Indeed, path consistency can be enforced by removing from a binary constraint all evaluations that cannot be extended to another variable. As for arc consistency, this removal might have to consider a binary constraint more than once. As for arc consistency, the resulting problem has the same solutions of the original one, as the removed values are in no solution.

The form of constraint propagation that enforces path consistency might introduce new constraints. When two variables are not related by a binary constraint, they are virtually related by the constraint allowing any pair of values. However, some pair of values might be removed by constraint propagation. The resulting constraint is no longer satisfied by all pairs of values. Therefore, it is no longer a virtual, trivial constraint.

The name "path consistency" derives from the original definition, which involved a pair of variables and a path between them, rather than a pair and a single variable. While the two definitions are different for a single pair of variables, they are equivalent when referring to the whole problem.

Generalizations

Arc and path consistency can be generalized to non-binary constraints using tuples of variables instead of a single one or a pair. A tuple of variables is -consistent with another variable if every consistent evaluation of the variables can be extended with a value of the other variable while preserving consistency. This definition extends to whole problems in the obvious way. Strong -consistency is -consistency for all .

The particular case of 2-consistency coincides with arc consistency (all problems are assumed node-consistent in this article). On the other hand, 3-consistency coincides with path consistency only if all constraints are binary, because path consistency does not involve ternary constraints while 3-consistency does.

Another way of generalizing arc consistency is hyper-arc consistency or generalized arc consistency, which requires extendibility of a single variable in order to satisfy a constraint. Namely, a variable is hyper-arc consistent with a constraint if every value of the variable can be extended to the other variables of the constraint in such a way the constraint is satisfied.

Consistency and satisfiability

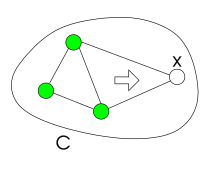

Constraint propagation (enforcing a form of local consistency) might produce an empty domain or an unsatisfiable constraint. In this case, the problem has no solution. The converse is not true in general: an inconsistent instance may be arc consistent or path consistent while having no empty domain or unsatisfiable constraint.

Indeed, local consistency is only relative to the consistency of groups of variables. For example, arc consistency guarantees that every consistent evaluation of a variable can be consistently extended to another variable. However, when a single value of a variable is extended to two other variables, there is no guarantee that these two values are consistent with each other. For example, may be consistent with and with , but these two evaluations may not be consistent with each other.

However, constraint propagation can be used to prove satisfiability in some cases. A set of binary constraints that is arc consistent and has no empty domain can be inconsistent only if the network of constraints contains cycles. Indeed, if the constraints are binary and form an acyclic graph, values can always be propagated across constraints: for every value of a variable, all variables in a constraint with it have a value satisfying that constraint. As a result, a solution can be found by iteratively choosing an unassigned variable and recursively propagating across constraints. This algorithm never tries to assign a value to a variable that is already assigned, as that would imply the existence of cycles in the network of constraints.

A similar condition holds for path consistency. The special cases in which satisfiability can be established by enforcing arc consistency and path consistency are the following ones.

- enforcing arc consistency establishes satisfiability of problems made of binary constraints with no cycles (a tree of binary constraints);

- enforcing path consistency establishes satisfiability for binary constraints (possibly with cycles) with binary domains;

- enforcing strong consistency establishes satisfiability of problems containing variables.

Special cases

Some definitions or results about relative consistency hold only in special cases.

When the domains are composed of integers, bound consistency can be defined. This form of consistency is based on the consistency of the extreme values of the domains, that is, the minimum and maximum values a variable can take.

When constraints are algebraic or Boolean, arc consistency is equivalent to adding new constraint or syntactically modifying an old one, and this can be done by suitably composing constraints.

Specialized constraints

Some kinds of constraints are commonly used. For example, the constraint that some variables are all different are often used. Efficient specialized algorithms for enforcing arc consistency on such constraints exist.

The constraint enforcing a number of variables to be different is usually written or alldifferent(). This constraint is equivalent to the non-equality of all pairs of different variables, that is, for every . When the domain of a variable is reduced to a single value, this value can be removed from all other domains by constraint propagation when enforcing arc consistency. The use of the specialized constraint allows for exploiting properties that do not hold for individual binary disequalities.

A first property is that the total number of elements in the domains of all variables must be at least the number of variables. More precisely, after arc consistency is enforced, the number of unassigned variables must not exceed the number of values in the union of their domains. Otherwise, the constraint cannot be satisfied. This condition can be checked easily on a constraint in the alldifferent form, but does not correspond to arc consistency of the network of disequalities. A second property of the single alldifferent constraint is that hyper-arc consistency can be efficiently checked using a bipartite matching algorithm. In particular, a graph is built with variables and values as the two sets of nodes, and a specialized bipartite graph matching algorithm is run on it to check the existence of such a matching.

A different kind of constraint that is commonly used is the cumulative one. It was introduced for problems of scheduling and placement. As an example, cumulative(, , , L) can be used to formalize the condition in which there are m activities, each one with starting time si, duration di and using an amount ri of a resource. The constraint states that the total available amount of resources is L. Specialized constraint propagation techniques for cumulative constraints exists; different techniques are used depending on which variable domains are already reduced to a single value.

A third specialized constraint that is used in constraint logic programming is the element one. In constraint logic programming, lists are allowed as values of variables. A constraint element(I, L, X) is satisfied if L is a list and X is the I-th element of this list. Specialized constraint propagation rules for these constraints exist. As an example, if L and I are reduced to a single-value domain, a unique value for X can be determined. More generally, impossible values of X can be inferred from the domain of and vice versa.

Directional consistency

Directional consistency is the variant of arc, path, and -consistency tailored for being used by an algorithm that assigns values to variables following a given order of variables. They are similar to their non-directional counterparts, but only require that a consistent assignment to some variables can be consistently extended to another variable that is greater than them according to the order.

Directional arc and path consistency

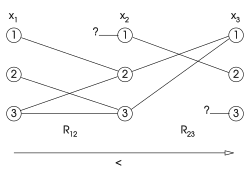

If an algorithm evaluates variables in the order , consistency is only useful when it guarantees that values of lower-index variables are all consistent with values of higher-index ones.

When choosing a value for a variable, values that are inconsistent with all values of an unassigned variable can be neglected. Indeed, even if these values are all consistent with the current partial evaluation, the algorithm will later fail to find a consistent value for the unassigned variable. On the other hand, enforcing consistency with variables that are already evaluated is not necessary: if the algorithm chooses a value that is inconsistent with the current partial evaluation, inconsistency is detected anyway.

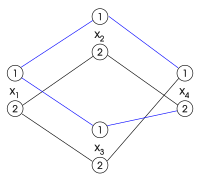

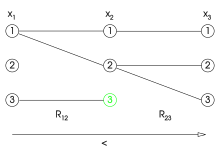

Assuming that the order of evaluation of the variables is , a constraint satisfaction problem is directionally arc consistent if every variable is arc consistent with any other variable such that . Directional path consistency is similar, but two variables have to be path consistent with only if . Strong directional path consistency means both directional path consistency and directional arc consistency. Similar definitions can be given for the other forms of consistency.

Constraint propagation for arc and path consistency

Constraint propagation enforcing directional arc consistency iterates over variables from the last to the first, enforcing at each step the arc consistency of every variable of lower index with it. If the order of the variables is , this algorithm iterates over variables from to ; for variable , it enforces arc consistency of every variable of index lower than with .

Directional path consistency and strong directional path consistency can be enforced by algorithms similar to the one for arc consistency. They process variables from to ; for every variable two variables with are considered, and path consistency of them with is enforced. No operation is required if the problem contains no constraint on and or no constraint between and . However, even if there is no constraint between and , a trivial one is assumed. If constraint propagation reduces its set of satisfying assignments, it effectively create a new non-trivial constraint. Constraint propagation enforcing strong directional path consistency is similar, but also enforces arc consistency.

Directional consistency and satisfiability

Directional consistency guarantees that partial solutions satisfying a constraint can be consistently extended to another variable of higher index. However, it does not guarantee that the extensions to different variables are consistent with each other. For example, a partial solution may be consistently extended to variable or to variable , but yet these two extensions are not consistent with each other.

There are two cases in which this does not happen, and directional consistency guarantees satisfiability if no domain is empty and no constraint is unsatisfiable.

The first case is that of a binary constraint problem with an ordering of the variables that makes the ordered graph of constraint having width 1. Such an ordering exists if and only if the graph of constraints is a tree. If this is the case, the width of the graph bounds the maximal number of lower (according to the ordering) nodes a node is joined to. Directional arc consistency guarantees that every consistent assignment to a variable can be extended to higher nodes, and width 1 guarantees that a node is not joined to more than one lower node. As a result, once the lower variable is assigned, its value can be consistently extended to every higher variable it is joined with. This extension cannot later lead to inconsistency. Indeed, no other lower variable is joined to that higher variable, as the graph has width 1.

As a result, if a constraint problem has width 1 with respect to an ordering of its variables (which implies that its corresponding graph is a tree) and the problem is directionally arc consistent with respect to the same ordering, a solution (if any) can be found by iteratively assigning variables according to the ordering.

The second case in which directional consistency guarantees satisfiability if no domain is empty and no constraint is unsatisfiable is that of binary constraint problems whose graph has induced width 2, using strong directional path consistency. Indeed, this form of consistency guarantees that every assignment to a variable or a pair of variables can be extended to a higher variable, and width 2 guarantees that this variable is not joined to another pair of lower variables.

The reason why the induced width is considered instead of the width is that enforcing directional path consistency may add constraints. Indeed, if two variables are not in the same constraint but are in a constraint with a higher variable, some pairs of their values may violate path consistency. Removing such pairs creates a new constraint. As a result, constraint propagation may produce a problem whose graph has more edges than the original one. However, all these edges are necessarily in the induced graph, as they are all between two parents of the same node. Width 2 guarantees that every consistent partial evaluation can be extended to a solution, but this width is relative to the generated graph. As a result, induced width being 2 is required for strong directional path consistency to guarantee the existence of solutions.

Directional i-consistency

Directional -consistency is the guarantee that every consistent assignment to variables can be consistently extended to another variable that is higher in the order. Strong directional -consistency is defined in a similar way, but all groups of at most variables are considered. If a problem is strongly directionally -consistent and has width less than and has no empty domain or unsatisfiable constraint, it has solutions.

Every problem can be made strongly directionally -consistent, but this operation may increase the width of its corresponding graphs. The constraint propagation procedure that enforces directional consistency is similar to that used for directional arc consistency and path consistency. The variables are considered in turn, from the last to the first according to the order. For variable , the algorithm considers every group of variables that have index lower than and are in a constraint with . Consistency of these variables with is checked and possibly enforced by removing satisfying assignments from the constraint among all these variables (if any, or creating a new one otherwise).

This procedure generates a strongly directional -consistent instance. However, it may also add new constraints to the instance. As a result, even if the width of the original problem is , the width of the resulting instance may be greater. If this is the case, directional strong consistency does not imply satisfiability even if no domain is empty and no constraint is unsatisfiable.

However, constraint propagation only adds constraints to variables that are lower than the one it is currently considering. As a result, no constraint over a variable is modified or added once the algorithm has dealt with this variable. Instead of considering a fixed , one can modify it to the number of parents of each considered variable (the parents of a variable are the variables of index lower than the variable and that are in a constraint with the variable). This corresponds to considering all parents of a given variables at each step. In other words, for each variable from the last to the first, all its parents are included in a new constraint that limits their values to the ones that are consistent with . Since this algorithm can be seen as a modification of the previous one with a value that is changed to the number of parents of each node, it is called adaptive consistency.

This algorithm enforces strongly directional -consistency with equal to the induced width of the problem. The resulting instance is satisfiable if and only if no domain or constraint is made empty. If this is the case, a solution can be easily found by iteratively setting an unassigned variable to an arbitrary value, and propagating this partial evaluation to other variables. This algorithm is not always polynomial-time, as the number of constraints introduced by enforcing strong directional consistency may produce an exponential increase of size. The problem is however solvable in polynomial time if the enforcing strong directional consistency does not superpolynomially enlarge the instance. As a result, if an instance has induced width bounded by a constant, it can be solved in polynomial time.

Bucket elimination

Bucket elimination is a satisfiability algorithm. It can be defined as a reformulation of adaptive consistency. Its definitions uses buckets, which are containers for constraint, each variable having an associated bucket. A constraint always belongs to the bucket of its highest variable.

The bucket elimination algorithm proceeds from the highest to the lowest variable in turn. At each step, the constraints in the buckets of this variable are considered. By definition, these constraints only involve variables that are lower than . The algorithm modifies the constraint between these lower variables (if any, otherwise it creates a new one). In particular, it enforces their values to be extendible to consistently with the constraints in the bucket of . This new constraint, if any, is then placed in the appropriate bucket. Since this constraint only involves variables that are lower than , it is added to a bucket of a variable that is lower than .

This algorithm is equivalent to enforcing adaptive consistency. Since they both enforce consistency of a variable with all its parents, and since no new constraint is added after a variable is considered, what results is an instance that can be solved without backtracking.

Since the graph of the instance they produce is a subgraph of the induced graph, if the induced width is bounded by a constant the generated instance is of size polynomial in the size of the original instance. As a result, if the induced width of an instance is bounded by a constant, solving it can be done in polynomial time by the two algorithms.

Relational consistency

While the previous definitions of consistency are all about consistency of assignments, relational consistency involves satisfaction of a given constraint or set of constraints only. More precisely, relational consistency implies that every consistent partial assignment can be extended in such a way that a given constraint or set of constraints is satisfied. Formally, a constraint on variables is relational arc consistent with one of its variables if every consistent assignment to can be extended to in such a way is satisfied. The difference between "regular" consistency and relational arc consistency is that the latter only requires the extended assignment to satisfy a given constraint, while the former requires it to satisfy all relevant constraints.

This definition can be extended to more than one constraint and more than one variable. In particular, relational path consistency is similar to relational arc consistency, but two constraints are used in place of one. Two constraints are relational path consistent with a variable if every consistent assignment to all their variables but the considered one can be extended in such a way the two constraints are satisfied.

For more than two constraints, relational -consistency is defined. Relational -consistency involves a set of constraints and a variable that is in the scope of all these constraints. In particular, these constraints are relational -consistent with the variable if every consistent assignment to all other variables that are in their scopes can be extended to the variable in such a way these constraints are satisfied. A problem is -relational consistent if every set of constraints is relational -consistent with every variable that is in all their scopes. Strong relational consistency is defined as above: it is the property of being relational -consistent for every .

Relational consistency can also be defined for more variables, instead of one. A set of constraints is relational -consistent if every consistent assignment to a subset of of their variables can be extended to an evaluation to all variables that satisfies all constraints. This definition does not exactly extends the above because the variables to which the evaluations are supposed to be extendible are not necessarily in all scopes of the involved constraints.

If an order of the variables is given, relational consistency can be restricted to the cases when the variables(s) the evaluation should be extendable to follow the other variables in the order. This modified condition is called directional relational consistency.

Relational consistency and satisfiability

A constraint satisfaction problem may be relationally consistent, have no empty domain or unsatisfiable constraint, and yet be unsatisfiable. There are however some cases in which this is not possible.

The first case is that of strongly relational -consistent problem when the domains contain at most elements. In this case, a consistent evaluation of variables can be always extended to a single other variable. If is such an evaluation and is the variable, there are only possible values the variable can take. If all such values are inconsistent with the evaluation, there are (non-necessarily unique) constraints that are violated by the evaluation and one of its possible values. As a result, the evaluation cannot be extended to satisfy all these -or-less constraints, violating the condition of strong relational -consistency.

The second case is related to a measure of the constraints, rather than the domains. A constraint is -tight if every evaluation to all its variables but one can be extended to satisfy the constraint either by all possible values of the other variable or by at most of its values. Problem having -tight constraints are satisfiable if and only if they are strongly relationally -consistent.

The third case is that of binary constraints that can be represented by row-convex matrices. A binary constraint can be represented by a bidimensional matrix , where is 0 or 1 depending on whether the -th value of the domain of and the -th value of the domain of satisfy the constraint. A row of this matrix is convex if the 1's it contains are consecutive (formally, if two elements are 1, all elements in between are 1 as well). A matrix is row convex if all its rows are convex.

The condition that makes strong relational path consistency equivalent to satisfiability is that of constraint satisfaction problems for which there exists an order of the variables that makes all constraint to be represented by row convex matrices. This result is based on the fact that a set of convex rows having a common element pairwise also have a globally common element. Considering an evaluation over variables, the allowed values for the -th one are given by selecting some rows from some constraints. In particular, for every variable among the ones, the row relative to its value in the matrix representing the constraint relating it with the one represents the allowed values of the latter. Since these row are convex, and they have a common element pairwise because of path consistency, they also have a shared common element, which represents a value of the last variable that is consistent with the other ones.

Uses of local consistency

All forms of local consistency can be enforced by constraint propagation, which may reduce the domains of variables and the sets of assignments satisfying a constraint and may introduce new constraints. Whenever constraint propagation produces an empty domain or an unsatisfiable constraint, the original problem is unsatisfiable. Therefore, all forms of local consistency can be used as approximations of satisfiability. More precisely, they can be used as incomplete unsatisfiability algorithms, as they can prove that a problem is unsatisfiable, but are in general unable to prove that a problem is satisfiable. Such approximated algorithms can be used by search algorithms (backtracking, backjumping, local search, etc.) as heuristics for telling whether a partial solution can be extended to satisfy all constraints without further analyzing it.

Even if constraint propagation does not produce an empty domain or an unsatisfiable constraint, it may nevertheless reduce the domains or strengthen the constraints. If this is the case, the search space of the problem is reduced, thus reducing the amount of search needed to solve the problem.

Local consistency proves satisfiability in some restricted cases (see Complexity of constraint satisfaction#Restrictions). This is the case for some special kind of problems and/or for some kinds of local consistency. For example, enforcing arc consistency on binary acyclic problems allows for telling whether the problem is satisfiable. Enforcing strong directional -consistency allows telling the satisfiability of problems that have induced width according to the same order. Adaptive directional consistency allows telling the satisfiability of an arbitrary problem.

See also

External links

- Constraint Propagation - Dissertation by Guido Tack giving a good survey of theory and implementation issues

References

- Régin, Jean-Charles (July 1994). "A filtering algorithm for constraints of difference in CSPs" (PDF). Proceedings of the AAAI Conference. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- Lecoutre, Christophe (2009). Constraint Networks: Techniques and Algorithms. ISTE/Wiley. ISBN 978-1-84821-106-3

- Dechter, Rina (2003). Constraint processing. Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN 1-55860-890-7

- Apt, Krzysztof (2003). Principles of constraint programming. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82583-0

- Marriott, Kim; Peter J. Stuckey (1998). Programming with constraints: An introduction. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-13341-5

with a domain of

with a domain of  and a constraint

and a constraint  , node consistency would restrict the domain to

, node consistency would restrict the domain to  and the constraint could then be discarded. This pre-processing step simplifies later stages.

and the constraint could then be discarded. This pre-processing step simplifies later stages.

is arc consistent with

is arc consistent with  but not with

but not with  , as the value

, as the value  is not compatible with any value for

is not compatible with any value for  is arc consistent with another variable

is arc consistent with another variable  if, for every value

if, for every value  in the domain of

in the domain of  in the domain of

in the domain of  satisfies the binary constraint between

satisfies the binary constraint between  where the variables range over the domain 1 to 3. Because

where the variables range over the domain 1 to 3. Because  can never be 3, there is no arc from 3 to a value in

can never be 3, there is no arc from 3 to a value in  so it is safe to remove. Likewise,

so it is safe to remove. Likewise,  if, for every pair of values

if, for every pair of values  in the domain of

in the domain of  and

and  satisfy the constraint between

satisfy the constraint between  variables is

variables is  -consistent with another variable if every consistent evaluation of the

-consistent with another variable if every consistent evaluation of the  -consistency for all

-consistency for all  .

.

may be consistent with

may be consistent with  , but these two evaluations may not be consistent with each other.

, but these two evaluations may not be consistent with each other.

consistency establishes satisfiability of problems containing

consistency establishes satisfiability of problems containing  or

or  for every

for every  . When the domain of a variable is reduced to a single value, this value can be removed from all other domains by constraint propagation when enforcing arc consistency. The use of the specialized constraint allows for exploiting properties that do not hold for individual binary

. When the domain of a variable is reduced to a single value, this value can be removed from all other domains by constraint propagation when enforcing arc consistency. The use of the specialized constraint allows for exploiting properties that do not hold for individual binary  and vice versa.

and vice versa.

, consistency is only useful when it guarantees that values of lower-index variables are all consistent with values of higher-index ones.

, consistency is only useful when it guarantees that values of lower-index variables are all consistent with values of higher-index ones.

. Directional path consistency is similar, but two variables

. Directional path consistency is similar, but two variables  have to be path consistent with

have to be path consistent with  only if

only if  . Strong directional path consistency means both directional path consistency and directional arc consistency. Similar definitions can be given for the other forms of consistency.

. Strong directional path consistency means both directional path consistency and directional arc consistency. Similar definitions can be given for the other forms of consistency.

to

to

does not correspond to any value of

does not correspond to any value of  does not correspond to any value of

does not correspond to any value of  are removed.

are removed.

and are in a constraint with

and are in a constraint with  on variables

on variables  is relational arc consistent with one of its variables

is relational arc consistent with one of its variables  can be extended to

can be extended to  -consistency is defined. Relational

-consistency is defined. Relational  .

.

-consistent if every consistent assignment to a subset of

-consistent if every consistent assignment to a subset of  is such an evaluation and

is such an evaluation and  is the variable, there are only

is the variable, there are only  -consistent.

-consistent.

, where

, where  is 0 or 1 depending on whether the

is 0 or 1 depending on whether the  -th one are given by selecting some rows from some constraints. In particular, for every variable among the

-th one are given by selecting some rows from some constraints. In particular, for every variable among the