| Corinth Canal | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Isthmus of Corinth |

| Country | Greece |

| Coordinates | 37°56′05″N 22°59′02″E / 37.93472°N 22.98389°E / 37.93472; 22.98389 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 6.34 km (3.94 miles) |

| Maximum boat beam | 24.6 m (81 ft) |

| Maximum boat draft | 7.3 m (24 ft) |

| Maximum boat air draft | 52 m (171 ft) |

| Locks | 0 |

| Status | Open (reopened in June 1, 2023 after being closed since January 2021) |

| Navigation authority | Corinth Canal S.A (A.E.DI.K) |

| History | |

| Principal engineer | István Türr and Béla Gerster |

| Construction began | 67 AD (first attempt) 1881 (final attempt) |

| Date of first use | 25 July 1893 |

| Date completed | 25 July 1893 |

The Corinth Canal (Greek: Διώρυγα της Κορίνθου, romanized: Dioryga tis Korinthou) is an artificial canal in Greece that connects the Gulf of Corinth in the Ionian Sea with the Saronic Gulf in the Aegean Sea. It cuts through the narrow Isthmus of Corinth and separates the Peloponnese from the Greek mainland, making the peninsula an island. The canal was dug through the Isthmus at sea level and has no locks. It is 6.4 kilometres (4 miles) in length and only 24.6 metres (80.7 feet) wide at sea level, making it impassable for many modern ships. It is currently of little economic importance and is mainly a tourist attraction.

The Corinth canal concept originated with Periander of Corinth in the 7th century BC. Daunted by its enormity, he chose to implement the Diolkos, a land trackway for transporting ships, instead. Construction of a canal finally began under Roman Emperor Nero in 67 AD, using Jewish prisoners captured during the First Jewish–Roman War. However, the project ceased shortly after his death. In subsequent centuries, the idea intrigued figures like Herodes Atticus in the second century and, following their conquest of the Peloponnese in 1687, the Venetians. Despite their interest, neither of them undertook the construction.

Construction finally recommenced in 1881 but was hampered by geological and financial problems that bankrupted the original builders. It was completed in 1893, but, due to the canal's narrowness, navigational problems, and periodic closures to repair landslides from its steep walls, it failed to attract the level of traffic expected by its operators.

History

Ancient attempts

Several rulers of antiquity dreamed of digging a cutting through the isthmus. The first to propose such an undertaking was the tyrant Periander in the 7th century BC. The project was abandoned and Periander instead constructed a simpler and less costly overland portage road, named the Diolkos or stone carriageway, along which ships could be towed from one side of the isthmus to the other. Periander's change of heart is attributed variously to the great expense of the project, a lack of labour or a fear that a canal would have robbed Corinth of its dominant role as an entrepôt for goods. Remnants of the Diolkos still exist next to the modern canal.

The Diadoch Demetrius Poliorcetes (336–283 BC) planned to construct a canal as a means to improve his communication lines, but dropped the plan after his surveyors, miscalculating the levels of the adjacent seas, feared heavy floods.

The philosopher Apollonius of Tyana prophesied that anyone who proposed to dig a Corinthian canal would be met with illness. Three Roman rulers considered the idea but all suffered violent deaths; the historians Plutarch and Suetonius both wrote that the Roman dictator Julius Caesar considered digging a canal through the isthmus but was assassinated before he could begin the project. Caligula, the third Roman Emperor, commissioned a study in 40 AD from Egyptian experts who claimed incorrectly that the Corinthian Gulf was higher than the Saronic Gulf. As a result, they concluded, if a canal were dug the island of Aegina would be inundated. Caligula's interest in the idea got no further as he too was assassinated before making any progress.

The emperor Nero was the first to attempt to construct the canal, personally breaking the ground with a pickaxe and removing the first basket-load of soil in 67 AD, but the project was abandoned when he died shortly afterwards. The Roman workforce, consisting of 6,000 Judean prisoners of war, started digging 40-to-50-metre-wide (130 to 160 ft) trenches from both sides, while a third group at the ridge drilled deep shafts for probing the quality of the rock (which were reused in 1881 for the same purpose). According to Suetonius, the canal was dug to a distance of four stades – approximately 700 metres (2,300 ft) – or about a tenth of the total distance across the isthmus. A memorial of the attempt in the form of a relief of Hercules was left by Nero's workers and can still be seen in the canal cutting today. Other than this, as the modern canal follows the same course as Nero's, no remains have survived.

The Greek philosopher and Roman senator Herodes Atticus is known to have considered digging a canal in the 2nd century AD, but did not get a project under way. The Venetians also considered it in 1687 after their conquest of the Peloponnese but likewise did not initiate any work on the ground.

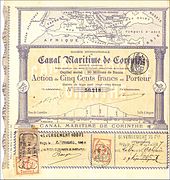

Construction of the modern canal

The idea of a canal was revived after Greece gained formal independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1830. The Greek statesman Ioannis Kapodistrias asked a French engineer to assess the feasibility of the project but had to abandon it when its cost was assessed at 40 million gold francs—far too expensive for the newly independent country. Fresh impetus was given by the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, and, the following year, the government of Prime Minister Thrasyvoulos Zaimis passed a law authorizing the construction of a Corinth canal. French entrepreneurs were put in charge but, following the bankruptcy of the French company that had attempted to dig the Panama Canal, French banks refused to lend money, and the company went bankrupt as well. A fresh concession was granted to the Société Internationale du Canal Maritime de Corinthe in 1881, which was commissioned to construct the canal and operate it for the next 99 years. Construction was formally inaugurated on 23 April 1882 in the presence of King George I of Greece.

The company's initial capital was 30,000,000 francs (US$6.0 million in the money of the day), but after eight years of work, it ran out of money, and a bid to issue 60,000 bonds of 500 francs each flopped when less than half of the bonds were sold. The company's head, István Türr, went bankrupt, as did the company itself and a bank that had agreed to raise additional funds for the project. Construction resumed in 1890, when the project was transferred to a Greek company, and was completed on 25 July 1893 after eleven years' work.

After completion

The canal experienced financial and operational difficulties after completion. The narrowness of the canal makes navigation difficult. Its high walls funnel wind along its length, and the different times of the tides in the two gulfs cause strong tidal currents in the channel. For these reasons, many ship operators were unwilling to use the canal, and traffic was far below predictions. Annual traffic of just under 4 million net tons had been anticipated, but by 1906 traffic had reached only half a million net tons annually. By 1913, the total had risen to 1.5 million net tons, but the disruption caused by World War I resulted in a major decline in traffic.

Another persistent problem was the heavily faulted nature of the sedimentary rock, in an active seismic zone, through which the canal is cut. The canal's high limestone walls have been persistently unstable from the start. Although it was formally opened in July 1893 it was not opened to navigation until the following November, due to landslides. It was soon found that the wake from ships passing through the canal undermined the walls, causing further landslides. This required further expense in building retaining walls along the water's edge for more than half of the length of the canal, using 165,000 cubic metres of masonry. Between 1893 and 1940, it was closed for a total of four years for maintenance to stabilise the walls. In 1923 alone, 41,000 cubic metres of material fell into the canal, which took two years to clear out.

Serious damage was caused to the canal during World War II. On 26 April 1941, during the Battle of Greece between defending Allied troops and the invading forces of Nazi Germany, German parachutists and glider troops attempted to capture the main bridge over the canal. The bridge was defended by British and Anzac forces and had been wired for demolition. The Germans surprised the defenders with a glider-borne assault in the early morning of 26 April and captured the bridge, but the British set off the charges and destroyed the structure. Other authors maintain that German pioneers cut the detonation wires, and a lucky hit by British artillery triggered the explosion, or that they were set off by a rifle shot from one of the British sappers. The bridge was replaced by a combined rail/road bridge built in 25 days by the IV Ferrovieri Battalion of the Royal Italian Army's Ferrovieri Engineer Regiment. Following the Axis occupation of Greece the Allies made several attempts to block the canal but without success.

In October 1944, as German forces retreated from Greece, the canal was put out of action by German "scorched earth" operations. German forces used explosives to trigger landslides to block the canal, destroyed the bridges and dumped locomotives, bridge wreckage and other infrastructure into the canal to hinder repairs. The United States Army Corps of Engineers began to clear the canal in November 1947 and reopened it for shallow-draft traffic by 7 July 1948, and for all traffic by that September.

Modern use

Because the canal is difficult to navigate for large vessels, it is mostly used by smaller recreational boats. A notable exception occurred on 9 October 2019, when the cruise ship MS Braemar became the widest and longest ship to transit the canal.

The canal closed at the beginning of 2021 after a landslide. It re-opened in June 2022 until October 2022. After further safety measures, the canal reopened on June 1, 2023.

Layout

The canal consists of a single channel 8 metres (26 ft) deep, excavated at sea level (thus requiring no locks), measuring 6,343 metres (20,810 ft) long by 24.6 metres (81 ft) wide at sea level and 21.3 metres (70 ft) wide at the bottom. The rock walls, which rise 90 metres (300 ft) above sea level, are at a near-vertical 80° angle. The canal is crossed by a railway line, a road and a motorway at a height of about 45 metres (148 ft). In 1988, submersible bridges were installed at sea level at each end of the canal, by the eastern harbour of Isthmia and the western harbour of Poseidonia, providing two additional crossings for road traffic.

Although the canal saves the 700-kilometre (430 mi) journey around the Peloponnese, it is too narrow for modern ocean freighters, as it can accommodate ships only of a width up to 17.6 metres (58 ft) and draft up to 7.3 metres (24 ft). In October 2019, with over 900 passengers on board, a 22.5 metres (74 ft) wide and 195 metres (640 ft) long Fred. Olsen Cruise Lines cruise ship successfully traversed the canal to set a new record for longest ship to pass through the canal. Ships can pass through the canal only one convoy at a time on a one-way system. Larger ships have to be towed by tugs. The canal is currently used mainly by tourist ships; around 11,000 ships per year travel through the waterway.

-

Aerial photograph of the Corinth Canal area (2011)

Aerial photograph of the Corinth Canal area (2011)

-

A submersible bridge at the entrance to the Corinth Canal

A submersible bridge at the entrance to the Corinth Canal

See also

References

- Facaros, Dana; Theodorou, Linda (1 May 2003). Greece. New Holland Publishers. p. 172. ISBN 978-1-86011-898-2. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ "The Canal: Specifications". Corinth Canal S.A (A.E.DI.K). Archived from the original on 8 August 2024. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ Clarke, Michael (4 September 2024). "Corinth Canal". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- "New Video Shows Corinth Canal – Greece's Suez – After Landslide". 31 May 2021.

- "PM visits closed Corinth Canal to inspect repair plan | eKathimerini.com". www.ekathimerini.com. 17 April 2021.

- "The Company: Our Vision". Corinth Canal S.A (A.E.DI.K). Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ Raepsaet, G. & Tolley, M.: "Le Diolkos de l’Isthme à Corinthe: son tracé, son fonctionnement", Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique, Vol. 117 (1993), pp. 233–261 (256)

- ^ Werner, Walter: "The largest ship trackway in ancient times: the Diolkos of the Isthmus of Corinth, Greece, and early attempts to build a canal", The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, Vol. 26, No. 2 (1997), pp. 98–119

- ^ Suetonius. "C. Suetonius Tranquillus, Nero, chapter 19". www.Perseus.Tufts.edu. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ^ Gerster, Béla, "L'Isthme de Corinthe: tentatives de percement dans l'antiquité", Bulletin de correspondance hellénique (1884), Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 225–232 (in French)

- ^ Wiseman, James (1978). The land of the ancient Corinthians. P. Åström. p. 50. ISBN 978-91-85058-78-5.

- ^ Setton, Kenneth Meyer (1991). Venice, Austria, and the Turks in the Seventeenth Century. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. p. 344. ISBN 0-87169-192-2.

- Verdelis, Nikolaos: "Le diolkos de L'Isthme", Bulletin de correspondance hellénique [fr], Vol. 81 (1957), pp. 526–529 (526)

- Cook, R. M.: "Archaic Greek Trade: Three Conjectures 1. The Diolkos", Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 99 (1979), pp. 152–155 (152)

- Drijvers, J.W.: "Strabo VIII 2,1 (C335): Porthmeia and the Diolkos", Mnemosyne, Vol. 45 (1992), pp. 75–76 (75)

- Lewis, M. J. T., "Railways in the Greek and Roman world" Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, in Guy, A. / Rees, J. (eds), Early Railways. A Selection of Papers from the First International Early Railways Conference (2001), pp. 8–19 (11)

- Verdelis, Nikolaos: "Le diolkos de L'Isthme", Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique (1957, 1958, 1960, 1961, 1963)

- Raepsaet, G. & Tolley, M.: "Le Diolkos de l’Isthme à Corinthe: son tracé, son fonctionnement", Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique, Vol. 117 (1993), pp. 233–261

- "Plutarch • Life of Caesar". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- Suetonius, "Lives of the Caesars: Julius Caesar", 44.3

- Facaros, Dana; Theodorou, Linda (2008). Peloponnese & Athens. New Holland Publishers. pp. 155–156. ISBN 978-1-86011-396-3.

- Arafat, K. W. (2004). Pausanias' Greece: Ancient Artists and Roman Rulers. Cambridge University Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-521-60418-5.

- ^ "The Countdown". Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ^ Johnson, Emory Richard (1920). Principles of Ocean Transportation. New York: D. Appleton. pp. 99–102.

- "Geology and Ancient Culture Along the Corinth Canal Archived 17 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine"

- "Corinth Canal". Johnson's Universal Cyclopedia: A New Edition, Vol. 7, p. 484. A.J. Johnson & Co., 1895

- "Corinth Canal History: 1923 A.C. — Nowadays". Archived from the original on 17 November 2007.

- ^ "CHAPTER 19 — The Corinth Canal | NZETC". nzetc.victoria.ac.nz. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- Mrazek, James (2011). Airborne Combat: Axis and Allied Glider Operations in World War II. Stackpole Books. pp. 49–55. ISBN 978-0-8117-0808-1.

- "108 Blau, George E. (1986) [1953]. The German Campaigns in the Balkans (Spring 1941) (Reissue ed.). Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 104-4.". Archived from the original on 27 January 2010. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- Absprung über dem Isthmus, Hans Rechenberg, in: Wir kämpften auf dem Balkan: VIII Fliegerkorps. Dr. Güntz-Druck, Dresden. 1941.

- Franzosi, Pier Giorgio (1991). L'Arma del Genio. Rome: Esercito Italiano – Rivista Militare. p. 224. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- Alexiades, Platon (2015). Target Corinth Canal 1940 - 1944: Mike Cumberlege and the attempts to block the Corinth Canal (1. publ. in Great Britain ed.). Barsnley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-4738-2756-1.

- Robert P. Grathwol; Donita M. Moorhus (2010). Bricks, Sand, and Marble: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Construction in the Mediterranean and Middle East, 1947–1991 (PDF). Government Printing Office. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-16-081738-0.

- Woodyatt, Amy (12 October 2019). "Huge cruise ship squeezes through Greek canal to claim record". CNN Travel. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- "Press Release: Information on Corinth Canal's transit suspension due to landslide | Α.Ε.ΔΙ.Κ." Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- "Corinth Canal reopens for traffic on June 1". 19 May 2023.

- "Greece Reopens Corinth Canal for the Tourist Season".

- "Corinth Canal". Aedik.gr. Archived from the original on 6 September 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- "Corinth Canal". Earth Observatory. NASA. 13 April 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- Carydis, Panayotis G.; Tilford, Norman R.; Brandow, Gregg E.; Jirsa, James O. (1982). The Central Greece earthquakes of February–March 1981. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. p. 79.

- ^ Goette, Hans Rupprecht (2001). Athens, Attica, and the Megarid: An Archaeological Guide. Routledge. p. 322.

- Bowman, Carol L. (February 2014). "The Corinth Canal". International Travel News. p. 12.

External links

- Official website

- Corinth Canal on Google Maps

- YouTube video of MS Braemar cruising the Corinth Canal