Cuncos, Juncos or Cunches is a poorly known subgroup of Huilliche people native to coastal areas of southern Chile and the nearby inland. Mostly a historic term, Cuncos are chiefly known for their long-running conflict with the Spanish during the colonial era of Chilean history.

Cuncos cultivated maize, potatoes and quinoa and raised chilihueques. Their economy was complemented by travels during spring and summer to the coast where they gathered shellfish and hunted sea lions. They were said to live in large rukas.

Cuncos were organized in small local chiefdoms forming a complex system intermarried families or clans with local allegiance.

Ethnicity and identity

The details of the identity of the Cuncos is not fully clear. José Bengoa defines "Cunco" as a category of indigenous Mapuche-Huilliche people in southern Chile used by the Spanish in colonial times. The Spanish referred to them as indios cuncos. Eugenio Alcamán cautions that the term "Cunco" in Spanish documents may not correspond to an ethnic group since they were defined, like other denominations for indigenous groups, chiefly on the basis of the territory they inhabited.

Ximena Urbina stresses that the differences between the southern Mapuche groups are poorly known but that their customs and language appear to have been the same. The Cuncos, she claims, are ethnically and culturally significantly more distant from the Araucanian Mapuche than neighboring (non-Cunco) Huilliches. Urbina also notes that the core group of the Cuncos distinguished themselves from the nearby Huilliches of the plains and the southern Cuncos of Maullín and Chiloé Archipelago by their staunch resistance to Spanish rule. That the Cuncos were a distinct group is also shown, according to Urbina, by the fact that the colonial Spanish also considered them the most barbarian of the southern Mapuche groups and that the Cuncos and (non-Cunco) Huilliche considered themselves different.

Territory

Further information: Futahuillimapu

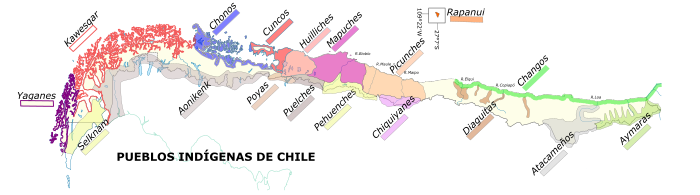

Jesuit Andrés Febrés mentions the Cuncos as inhabiting the area between Valdivia and Chiloé. Tapping on Febrés work Lorenzo Hervás y Panduro writes that Cuncos inhabit the mainland north of Chiloé Archipelago as far north as to limit with "Araucanian barbarians" (Mapuche from Araucanía). Hervás y Panduro list them as one of three "Chilean barbarians" groups inhabiting the territory between latitudes 36° S and 41° S, the other being the Araucanians and Huilliche. The Cuncos lived in the Chilean Coast Range and its foothills. Proper Huilliches lived east of them in the flatlands of the Central Valley. There are differing views on the southern extent of the Cunco lands, some accounts mention the Maullín River as the limit while other say the Cuncos inhabited the land all the way to the middle of Chiloé Island. A theory postulated by chronicler José Pérez García holds the Cuncos settled in Chiloé Island in Pre-Hispanic times as consequence of a push from more northern Huilliches who in turn were being displaced by Mapuches. The indigenous inhabitants of the northern half of Chiloé Island, of Mapuche culture, are variously referred as Cunco, Huilliche or Veliche.

The lands of the Cunco were described in colonial sources as rainy and rich in swamps, rivers, streams with thick forests with stout and tall trees. Flat and cleared terrain was scarce and local roads very narrow and of poor quality.

The Cuncos should not be confused with Cuncos from the locality of Cunco further north.

Language

Lorenzo Hervás y Panduro mention the language of cuncos as an accent or dialect similar to "Chiloense", the language of the indigenous people of Chiloé Archipelago, asserting the languages of Huilliches, Cuncos, Pehuenches and Araucanians (Mapuche) were mutually intelligible.

Conflict with the Spanish

Ever since the Destruction of Osorno the Cuncos had bad relations with the Spanish settlements of Calbuco and Carelmapu formed by exiles from Osorno and loyalist Indians. Indeed, the area between Reloncaví Sound and Maipué River was depopulated as a consequence of this conflict that not only included warfare but slave raiding too.

On March 21, 1651, Spanish ship San José aimed to the newly re-established Spanish city of Valdivia was pushed by storms into coasts inhabited by the Cuncos south of Valdivia. There the ship ran aground and while most of the crew managed to survive the wreck nearby Cuncos killed them and took possession of the valuable cargo. The Spanish made fruitless efforts to recover anything left in wreck. Two punitive expeditions were assembled one started in Valdivia advancing south and the other in Carelmapu advancing north. The expedition from Valdivia turned into a failure as Mapuches who were expected to aid the Spanish as Indian auxiliaries according to the Parliament of Boroa did not support the Spanish expedition. While away from Valdivia hostile local Mapuches killed twelve Spanish. The expedition from Valdivia soon ran out of supplies and decided to return to Valdivia without having confronted the Cuncos. The expedition from Carelmapu was more successful reaching the site of abandoned city of Osorno. Here the Spanish were approached by Huilliches who gave them three caciques who were allegedly involved in the looting and murder of the wrecked Spanish. Governor of Chile Antonio de Acuña Cabrera planned a new Spanish punitive expedition against the Cuncos but was dissuaded by Jesuits who warned him that any large military assault would endanger the accords of the Parliament of Boroa.

The indios cuncos were the subject of Juan de Salazar's failed slave raid in 1654 that ended in a Spanish defeat at the Battle of Río Bueno. This battle served as catalyst for the devastating Mapuche uprising of 1655.

Albeit the Cuncos had occasional conflicts with the Spanish from Valdivia as in the 1650s and 1750s, over-all relations towards the Spanish of Calbuco, Carelmapu and Chiloé were more hostile. Indeed, the Spanish in Valdivia were able to slowly advance their positions by trade and land purchases in the second half of the 18th century. Eventually Spanish domains reached all the way from Valdivia to Bueno River. Amidst a period of renewed conflict in 1770 the Spanish destroyed a road the Cuncos had built from Punta Galera to Corral to attack the Spanish. Following a devastating raid of Tomás de Figueroa through Futahuillimapu in 1792, Cunco apo ülmen Paylapan (Paill’apangi) sent messengers (wesrkin) to participate in negotiations with the Spanish at the Parliament of Las Canoas.

Notes

- A misspelling according to Lorenzo Hervás y Panduro.

- As recorded in Ernesto Wilhelm de Moesbach's 1944 book Voz de Arauco.

- Huilliches themselves are a southern subgroup of the Mapuche macro-ethnicity.

- About this region Febrés adds: "which we hope to subdue soon".

- Archaeologist and ethnographer Ricardo E. Latcham built upon on this notion and held this invasion happened in the 13th century and that as consequence of it native Chono migrated south to Guaitecas Archipelago from Chiloé Archipelago.

References

- ^ Hervás y Panduro 1800, p. 127.

- de Moesbach, Ernesto Wilhelm (2016) . Voz de Arauco (in Spanish). Santiago: Ceibo. p. 56. ISBN 978-956-359-051-7.

- ^ Alcamán 1997, p. 32.

- ^ Urbina 2009, p. 44.

- Alcamán 1997, p. 47.

- ^ Bengoa 2000, p. 122.

- Alcamán 1997, p. 29.

- Urbina 2009, p. 34.

- Febrés 1765, p. 465.

- ^ Hervás y Panduro 1800, p. 128.

- ^ Alcamán 1997, p. 33.

- Cárdenas et al. 1991, p. 34

- "Poblaciones costeras de Chile: marcadores genéticos en cuatro localidades". Revista médica de Chile. 126 (7). 1998. doi:10.4067/S0034-98871998000700002.

- ^ Alcamán 1997, p. 30.

- ^ Barros Arana 2000, p. 340.

- ^ Barros Arana 2000, p. 341.

- ^ Barros Arana 2000, p. 342.

- Barros Arana 2000, p. 343.

- Barros Arana 2000, p. 346.

- Barros Arana 2000, p. 347.

- Barros Arana 2000, p. 359.

- ^ Couyoumdjian, Juan Ricardo (2009). "Reseña de "La frontera de arriba en Chile colonial. Interacción hispano-indígena en el territorio entre Valdivia y Chiloé e imaginario de sus bordes geográficos, 1600-1800" de MARÍA XIMENA URBINA CARRASCO" (PDF). Historia. I (42): 281–283. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- Illanes Oliva, M. Angélica (2014). "La cuarta frontera. El caso del territorio valdiviano (Chile, XVII–XIX)". Atenea. 509: 227–243. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- Guarda Geywitz, Fernando (1953). Historia de Valdivia (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: Imprenta Cultura. p. 155.

- Rumian Cisterna, Salvador (2020-09-17). Gallito Catrilef: Colonialismo y defensa de la tierra en San Juan de la Costa a mediados del siglo XX (M.Sc. thesis) (in Spanish). University of Los Lagos.

Bibliography

- Alcamán, Eugenio (1997). "Los mapuche-huilliche del Futahuillimapu septentrional: Expansión colonial, guerras internas y alianzas políticas (1750–1792)" (PDF). Revista de Historia Indígena (in Spanish) (2): 29–76. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-28.

- Barros Arana, Diego. "Capítulo XIV". Historia general de Chile (in Spanish). Vol. Tomo cuarto (Digital edition based on the second edition of 2000 ed.). Alicante: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes.

- Bengoa, José (2000). Historia del pueblo mapuche: Siglos XIX y XX (in Spanish) (Seventh ed.). LOM Ediciones. p. 122. ISBN 978-956-282-232-9.

- Cárdenas A., Renato; Montiel Vera, Dante; Grace Hall, Catherine (1991). Los chono y los veliche de Chiloé (PDF) (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: Olimpho.

- Febrés, Andrés (1765). Arte de la lengua general del Reyno de Chile, con un diálogo chileno-hispano muy curioso : a que se añade la doctrina christiana, esto es, rezo, catecismo, coplas, confesionario, y pláticas, lo más en lengua chilena y castellana : y por fin un vocabulario hispano-chileno, y un calepino chileno-hispano mas copioso (in Spanish). Lima. p. 465.

- Hervás y Panduro, Lorenzo (1800). Catálogo de las lenguas de las naciones conocidas, y numeracion, division, y clases de estas sugún la diversidad de sus idiomas y dialectos (in Spanish). Madrid.

- Urbina Carrasco, Ximena (2009). La Frontera de arriba en Chile Colonial: Interacción hispano-indígena en el territorio entre Valdivia y Chiloé e imaginario de sus bordes geográficos, 1600–1800 (in Spanish). Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso. ISBN 978-956-17-0433-6.