| Part of a series on |

| Power engineering |

|---|

| Electric power conversion |

| Electric power infrastructure |

| Electric power systems components |

A power inverter, inverter, or invertor is a power electronic device or circuitry that changes direct current (DC) to alternating current (AC). The resulting AC frequency obtained depends on the particular device employed. Inverters do the opposite of rectifiers which were originally large electromechanical devices converting AC to DC.

The input voltage, output voltage and frequency, and overall power handling depend on the design of the specific device or circuitry. The inverter does not produce any power; the power is provided by the DC source.

A power inverter can be entirely electronic or maybe a combination of mechanical effects (such as a rotary apparatus) and electronic circuitry. Static inverters do not use moving parts in the conversion process.

Power inverters are primarily used in electrical power applications where high currents and voltages are present; circuits that perform the same function for electronic signals, which usually have very low currents and voltages, are called oscillators. Circuits that perform the opposite function, converting AC to DC, are called rectifiers.

Input and output

Input voltage

A typical power inverter device or circuit requires a stable DC power source capable of supplying enough current for the intended power demands of the system. The input voltage depends on the design and purpose of the inverter. Examples include:

- 12 V DC, for smaller consumer and commercial inverters that typically run from a rechargeable 12 V lead acid battery or automotive electrical outlet.

- 24, 36, and 48 V DC, which are common standards for home energy systems.

- 200 to 400 V DC, when power is from photovoltaic solar panels.

- 300 to 450 V DC, when power is from electric vehicle battery packs in vehicle-to-grid systems.

- Hundreds of thousands of volts, where the inverter is part of a high-voltage direct current power transmission system.

Output waveform

An inverter may produce a square wave, sine wave, modified sine wave, pulsed sine wave, or near-sine pulse-width modulated wave (PWM) depending on circuit design. Common types of inverters produce square waves or quasi-square waves. One measure of the purity of a sine wave is the total harmonic distortion (THD). Technical standards for commercial power distribution grids require less than 3% THD in the wave shape at the customer's point of connection. IEEE Standard 519 recommends less than 5% THD for systems connecting to a power grid.

There are two basic designs for producing household plug-in voltage from a lower-voltage DC source, the first of which uses a switching boost converter to produce a higher-voltage DC and then converts to AC. The second method converts DC to AC at battery level and uses a line-frequency transformer to create the output voltage.

Square wave

A 50% duty cycle square wave is one of the simplest waveforms an inverter design can produce, but adds ~48.3% THD to its fundamental sine wave. Thus, a square wave output can produce undesired "humming" noises when connected to audio equipment and is better suited to low-sensitivity applications such as lighting and heating.

Sine wave

A power inverter device that produces a multiple step sinusoidal AC waveform is referred to as a sine wave inverter. To more clearly distinguish the inverters with outputs of much less distortion than the modified sine wave (three-step) inverter designs, the manufacturers often use the phrase pure sine wave inverter. Almost all consumer grade inverters that are sold as a "pure sine wave inverter" do not produce a smooth sine wave output at all, just a less choppy output than the square wave (two-step) and modified sine wave (three-step) inverters. However, this is not critical for most electronics as they deal with the output quite well.

Where power inverter devices substitute for standard line power, a sine wave output is desirable because many electrical products are engineered to work best with a sine wave AC power source. The standard electric utility provides a sine wave, typically with minor imperfections but sometimes with significant distortion.

Sine wave inverters with more than three steps in the wave output are more complex and have significantly higher cost than a modified sine wave, with only three steps, or square wave (one step) types of the same power handling. Switched-mode power supply (SMPS) devices, such as personal computers or DVD players, function on modified sine wave power. AC motors directly operated on non-sinusoidal power may produce extra heat, may have different speed-torque characteristics, or may produce more audible noise than when running on sinusoidal power.

Modified sine wave

The modified sine wave is the sum of two square waves, one of which is delayed one-quarter of the period with respect to the other. The result is a repeated voltage step sequence of zero, peak positive, zero, peak negative, and again zero. The resultant voltage waveform better approximates the shape of a sinusoidal voltage waveform than a single square wave. Most inexpensive consumer power inverters produce a modified sine wave rather than a pure sine wave.

If the waveform is chosen to have its peak voltage values for half of the cycle time, the peak voltage to RMS voltage ratio is the same as for a sine wave. The DC bus voltage may be actively regulated, or the "on" and "off" times can be modified to maintain the same RMS value output up to the DC bus voltage to compensate for DC bus voltage variations. By changing the pulse width, the harmonic spectrum can be changed. The lowest THD for a three-step modified sine wave is 30% when the pulses are at 130 degrees width of each electrical cycle. This is slightly lower than for a square wave.

The ratio of on to off time can be adjusted to vary the RMS voltage while maintaining a constant frequency with a technique called pulse-width modulation (PWM). The generated gate pulses are given to each switch in accordance with the developed pattern to obtain the desired output. The harmonic spectrum in the output depends on the width of the pulses and the modulation frequency. It can be shown that the minimum distortion of a three-level waveform is reached when the pulses extend over 130 degrees of the waveform, but the resulting voltage will still have about 30% THD, higher than commercial standards for grid-connected power sources. When operating induction motors, voltage harmonics are usually not of concern; however, harmonic distortion in the current waveform introduces additional heating and can produce pulsating torques.

Numerous items of electric equipment will operate quite well on modified sine wave power inverter devices, especially loads that are resistive in nature such as traditional incandescent light bulbs. Items with a switched-mode power supply operate almost entirely without problems, but if the item has a mains transformer, this can overheat depending on how marginally it is rated.

However, the load may operate less efficiently owing to the harmonics associated with a modified sine wave and produce a humming noise during operation. This also affects the efficiency of the system as a whole, since the manufacturer's nominal conversion efficiency does not account for harmonics. Therefore, pure sine wave inverters may provide significantly higher efficiency than modified sine wave inverters.

Most AC motors will run on MSW inverters with an efficiency reduction of about 20% owing to the harmonic content. However, they may be quite noisy. A series LC filter tuned to the fundamental frequency may help.

A common modified sine wave inverter topology found in consumer power inverters is as follows: An onboard microcontroller rapidly switches on and off power MOSFETs at high frequency like ~50 kHz. The MOSFETs directly pull from a low voltage DC source (such as a battery). This signal then goes through step-up transformers (generally many smaller transformers are placed in parallel to reduce the overall size of the inverter) to produce a higher voltage signal. The output of the step-up transformers then gets filtered by capacitors to produce a high voltage DC supply. Finally, this DC supply is pulsed with additional power MOSFETs by the microcontroller to produce the final modified sine wave signal.

More complex inverters use more than two voltages to form a multiple-stepped approximation to a sine wave. These can further reduce voltage and current harmonics and THD compared to an inverter using only alternating positive and negative pulses; but such inverters require additional switching components, increasing cost.

Near sine wave PWM

Some inverters use PWM to create a waveform that can be low pass filtered to re-create the sine wave. These only require one DC supply, in the manner of the MSN designs, but the switching takes place at a far faster rate, typically many kHz, so that the varying width of the pulses can be smoothed to create the sine wave. If a microprocessor is used to generate the switching timing, the harmonic content and efficiency can be closely controlled.

Output frequency

The AC output frequency of a power inverter device is usually the same as standard power line frequency, 50 or 60 hertz. The exception is in designs for motor driving, where a variable frequency results in a variable speed control.

Also, if the output of the device or circuit is to be further conditioned (for example stepped up) then the frequency may be much higher for good transformer efficiency.

Output voltage

The AC output voltage of a power inverter is often regulated to be the same as the grid line voltage, typically 120 or 240 VAC at the distribution level, even when there are changes in the load that the inverter is driving. This allows the inverter to power numerous devices designed for standard line power.

Some inverters also allow selectable or continuously variable output voltages.

Output power

A power inverter will often have an overall power rating expressed in watts or kilowatts. This describes the power that will be available to the device the inverter is driving and, indirectly, the power that will be needed from the DC source. Smaller popular consumer and commercial devices designed to mimic line power typically range from 150 to 3000 watts.

Not all inverter applications are solely or primarily concerned with power delivery; in some cases the frequency and or waveform properties are used by the follow-on circuit or device.

Batteries

The runtime of an inverter powered by batteries is dependent on the battery power and the amount of power being drawn from the inverter at a given time. As the amount of equipment using the inverter increases, the runtime will decrease. In order to prolong the runtime of an inverter, additional batteries can be added to the inverter.

Formula to calculate inverter battery capacity:

Battery Capacity (Ah) = Total Load (In Watts) × Usage Time (in hours) / Input Voltage (V)

When attempting to add more batteries to an inverter, there are two basic options for installation:

- Series configuration

- If the goal is to increase the overall input voltage to the inverter, one can daisy chain batteries in a series configuration. In a series configuration, if a single battery dies, the other batteries will not be able to power the load.

- Parallel configuration

- If the goal is to increase capacity and prolong the runtime of the inverter, batteries can be connected in parallel. This increases the overall ampere hour (Ah) rating of the battery set. If a single battery is discharged though, the other batteries will then discharge through it. This can lead to rapid discharge of the entire pack, or even an overcurrent and possible fire. To avoid this, large paralleled batteries may be connected via diodes or intelligent monitoring with automatic switching to isolate an under-voltage battery from the others.

Applications

DC power source usage

An inverter converts the DC electricity from sources such as batteries or fuel cells to AC electricity. The electricity can be at any required voltage; in particular it can operate AC equipment designed for mains operation, or rectified to produce DC at any desired voltage.

Uninterruptible power supplies

An uninterruptible power supply (UPS) uses batteries and an inverter to supply AC power when mains power is not available. When mains power is restored, a rectifier supplies DC power to recharge the batteries.

Electric motor speed control

Inverter circuits designed to produce a variable output voltage range are often used within motor speed controllers. The DC power for the inverter section can be derived from a normal AC wall outlet or some other source. Control and feedback circuitry is used to adjust the final output of the inverter section which will ultimately determine the speed of the motor operating under its mechanical load. Motor speed control needs are numerous and include things like: industrial motor driven equipment, electric vehicles, rail transport systems, and power tools. (See related: variable-frequency drive) Switching states are developed for positive, negative, and zero voltages as per the patterns given in the switching Table 1. The generated gate pulses are given to each switch in accordance with the developed pattern and thus the output is obtained.

In refrigeration compressors

An inverter can be used to control the speed of the compressor motor to drive variable refrigerant flow in a refrigeration or air conditioning system to regulate system performance. Such installations are known as inverter compressors. Traditional methods of refrigeration regulation use single-speed compressors switched on and off periodically; inverter-equipped systems have a variable-frequency drive that controls the speed of the motor and thus the compressor and cooling output. The variable-frequency AC from the inverter drives a brushless or induction motor, the speed of which is proportional to the frequency of the AC it is fed, so the compressor can be run at variable speeds—eliminating compressor stop-start cycles increases efficiency. A microcontroller typically monitors the temperature in the space to be cooled, and adjusts the speed of the compressor to maintain the desired temperature. The additional electronics and system hardware add cost to the equipment, but can result in substantial savings in operating costs. The first inverter air conditioners were released by Toshiba in 1981, in Japan.

Power grid

Grid-tied inverters are designed to feed into the electric power distribution system. They transfer synchronously with the line and have as little harmonic content as possible. They also need a means of detecting the presence of utility power for safety reasons, so as not to continue to dangerously feed power to the grid during a power outage.

Synchronverters are inverters that are designed to simulate a rotating generator, and can be used to help stabilize grids. They can be designed to react faster than normal generators to changes in grid frequency, and can give conventional generators a chance to respond to very sudden changes in demand or production.

Large inverters, rated at several hundred megawatts, are used to deliver power from high-voltage direct current transmission systems to alternating current distribution systems.

Solar

A solar inverter is a balance of system (BOS) component of a photovoltaic system and can be used for both grid-connected and off-grid (standalone) systems. Solar inverters have special functions adapted for use with photovoltaic arrays, including maximum power point tracking and anti-islanding protection.

Solar micro-inverters differ from conventional inverters, as an individual micro-inverter is attached to each solar panel. This can improve the overall efficiency of the system. The output from several micro-inverters is then combined and often fed to the electrical grid.

In other applications, a conventional inverter can be combined with a battery bank maintained by a solar charge controller. This combination of components is often referred to as a solar generator.

Solar inverters are also used in spacecraft photovoltaic systems.

Induction heating

Inverters convert low frequency main AC power to higher frequency for use in induction heating. To do this, AC power is first rectified to provide DC power. The inverter then changes the DC power to high frequency AC power. Due to the reduction in the number of DC sources employed, the structure becomes more reliable and the output voltage has higher resolution due to an increase in the number of steps so that the reference sinusoidal voltage can be better achieved. This configuration has recently become very popular in AC power supply and adjustable speed drive applications. This new inverter can avoid extra clamping diodes or voltage balancing capacitors.

There are three kinds of level shifted modulation techniques, namely:

- Phase opposition disposition (POD)

- Alternative phase opposition disposition (APOD)

- Phase disposition (PD)

HVDC power transmission

With HVDC power transmission, AC power is rectified and high voltage DC power is transmitted to another location. At the receiving location, an inverter in a HVDC converter station converts the power back into AC. The inverter must be synchronized with grid frequency and phase and minimize harmonic generation.

Electroshock weapons

Electroshock weapons and tasers have a DC/AC inverter to generate several tens of thousands of V AC out of a small 9 V DC battery. First the 9 V DC is converted to 400–2000 V AC with a compact high frequency transformer, which is then rectified and temporarily stored in a high voltage capacitor until a pre-set threshold voltage is reached. When the threshold (set by way of an airgap or TRIAC) is reached, the capacitor dumps its entire load into a pulse transformer which then steps it up to its final output voltage of 20–60 kV. A variant of the principle is also used in electronic flash and bug zappers, though they rely on a capacitor-based voltage multiplier to achieve their high voltage.

Miscellaneous

Typical applications for power inverters include:

- Portable consumer devices that allow the user to connect a battery, or set of batteries, to the device to produce AC power to run various electrical items such as lights, televisions, kitchen appliances, and power tools.

- Use in power generation systems such as electric utility companies or solar generating systems to convert DC power to AC power.

- Use within any larger electronic system where an engineering need exists for deriving an AC source from a DC source. For example, a DC-powered electronic device may contain a small inverter to power an electroluminescent or fluorescent backlight, which requires high-frequency AC,

- Utility frequency conversion - if a user in (say) a 50 Hz country needs a 60 Hz supply to power equipment that is frequency-specific, such as a small motor or some electronics, it is possible to convert the frequency by running an inverter with a 60 Hz output from a DC source such as a 12V power supply running from the 50 Hz mains.

Circuit description

Basic design

In one simple inverter circuit, DC power is connected to a transformer through the center tap of the primary winding. A relay switch is rapidly switched back and forth to allow current to flow back to the DC source following two alternate paths through one end of the primary winding and then the other. The alternation of the direction of current in the primary winding of the transformer produces alternating current (AC) in the secondary circuit.

The electromechanical version of the switching device includes two stationary contacts and a spring supported moving contact. The spring holds the movable contact against one of the stationary contacts and an electromagnet pulls the movable contact to the opposite stationary contact. The current in the electromagnet is interrupted by the action of the switch so that the switch continually switches rapidly back and forth. This type of electromechanical inverter switch, called a vibrator or buzzer, was once used in vacuum tube automobile radios. A similar mechanism has been used in door bells, buzzers, and tattoo machines.

As they became available with adequate power ratings, transistors, and various other types of semiconductor switches have been incorporated into inverter circuit designs. Certain ratings, especially for large systems (many kilowatts) use thyristors (SCR). SCRs provide large power handling capability in a semiconductor device, and can readily be controlled over a variable firing range.

The switch in the simple inverter described above, when not coupled to an output transformer, produces a square voltage waveform due to its simple off and on nature as opposed to the sinusoidal waveform that is the usual waveform of an AC power supply. Using Fourier analysis, periodic waveforms are represented as the sum of an infinite series of sine waves. The sine wave that has the same frequency as the original waveform is called the fundamental component. The other sine waves, called harmonics, that are included in the series have frequencies that are integral multiples of the fundamental frequency.

Fourier analysis can be used to calculate the total harmonic distortion (THD). The total harmonic distortion (THD) is the square root of the sum of the squares of the harmonic voltages divided by the fundamental voltage:

Advanced designs

There are many different power circuit topologies and control strategies used in inverter designs. Different design approaches address various issues that may be more or less important depending on the way that the inverter is intended to be used. For example, an electric motor in a car that is moving can turn into a source of energy and can, with the right inverter topology (full H-bridge) charge the car battery when decelerating or braking. In a similar manner, the right topology (full H-bridge) can invert the roles of "source" and "load", that is, if for example the voltage is higher on the AC "load" side (by adding a solar inverter, similar to a gen-set, but solid state), energy can flow back into the DC "source" or battery.

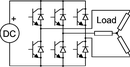

Based on the basic H-bridge topology, there are two different fundamental control strategies called basic frequency-variable bridge converter and PWM control. Here, in the left image of H-bridge circuit, the top left switch is named as "S1", and others are named as "S2, S3, S4" in counterclockwise order.

For the basic frequency-variable bridge converter, the switches can be operated at the same frequency as the AC in the electric grid. However, it is the rate at which the switches open and close that determines the AC frequency. When S1 and S4 are on and the other two are off, the load is provided with positive voltage and vice versa. We could control the on-off states of the switches to adjust the AC magnitude and phase. We could also control the switches to eliminate certain harmonics. This includes controlling the switches to create notches, or 0-state regions, in the output waveform or adding the outputs of two or more converters in parallel that are phase shifted in respect to one another.

Another method that can be used is PWM. Unlike the basic frequency-variable bridge converter, in the PWM controlling strategy, only two switches S3, S4 can operate at the frequency of the AC side or at any low frequency. The other two would switch much faster (typically 100 kHz) to create square voltages of the same magnitude but for different time duration, which behaves like a voltage with changing magnitude in a larger time-scale.

These two strategies create different harmonics. For the first one, through Fourier Analysis, the magnitude of harmonics would be 4/(pi*k) (k is the order of harmonics). So the majority of the harmonics energy is concentrated in the lower order harmonics. Meanwhile, for the PWM strategy, the energy of the harmonics lie in higher-frequencies because of the fast switching. Their different characteristics of harmonics leads to different THD and harmonics elimination requirements. Similar to "THD", the conception "waveform quality" represents the level of distortion caused by harmonics. The waveform quality of AC produced directly by H-bridge mentioned above would be not as good as we want.

The issue of waveform quality can be addressed in many ways. Capacitors and inductors can be used to filter the waveform. If the design includes a transformer, filtering can be applied to the primary or the secondary side of the transformer or to both sides. Low-pass filters are applied to allow the fundamental component of the waveform to pass to the output while limiting the passage of the harmonic components. If the inverter is designed to provide power at a fixed frequency, a resonant filter can be used. For an adjustable frequency inverter, the filter must be tuned to a frequency that is above the maximum fundamental frequency.

Since most loads contain inductance, feedback rectifiers or antiparallel diodes are often connected across each semiconductor switch to provide a path for the peak inductive load current when the switch is turned off. The antiparallel diodes are somewhat similar to the freewheeling diodes used in AC/DC converter circuits.

| Waveform | Signal transitions per period |

Harmonics eliminated |

Harmonics amplified |

System description |

THD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2 | 2-level square wave |

~45% | ||

|

4 | 3, 9, 27, ... | 3-level modified sine wave |

>23.8% | |

|

8 | 5-level modified sine wave |

>6.5% | ||

|

10 | 3, 5, 9, 27 | 7, 11, ... | 2-level very slow PWM |

|

|

12 | 3, 5, 9, 27 | 7, 11, ... | 3-level very slow PWM |

Fourier analysis reveals that a waveform, like a square wave, that is anti-symmetrical about the 180 degree point contains only odd harmonics, the 3rd, 5th, 7th, etc. Waveforms that have steps of certain widths and heights can attenuate certain lower harmonics at the expense of amplifying higher harmonics. For example, by inserting a zero-voltage step between the positive and negative sections of the square-wave, all of the harmonics that are divisible by three (3rd, 9th, etc.) can be eliminated. That leaves only the 5th, 7th, 11th, 13th, etc. The required width of the steps is one third of the period for each of the positive and negative steps and one sixth of the period for each of the zero-voltage steps.

Changing the square wave as described above is an example of pulse-width modulation. Modulating, or regulating the width of a square-wave pulse is often used as a method of regulating or adjusting an inverter's output voltage. When voltage control is not required, a fixed pulse width can be selected to reduce or eliminate selected harmonics. Harmonic elimination techniques are generally applied to the lowest harmonics because filtering is much more practical at high frequencies, where the filter components can be much smaller and less expensive. Multiple pulse-width or carrier based PWM control schemes produce waveforms that are composed of many narrow pulses. The frequency represented by the number of narrow pulses per second is called the switching frequency or carrier frequency. These control schemes are often used in variable-frequency motor control inverters because they allow a wide range of output voltage and frequency adjustment while also improving the quality of the waveform.

Multilevel inverters provide another approach to harmonic cancellation. Multilevel inverters provide an output waveform that exhibits multiple steps at several voltage levels. For example, it is possible to produce a more sinusoidal wave by having split-rail direct current inputs at two voltages, or positive and negative inputs with a central ground. By connecting the inverter output terminals in sequence between the positive rail and ground, the positive rail and the negative rail, the ground rail and the negative rail, then both to the ground rail, a stepped waveform is generated at the inverter output. This is an example of a three-level inverter: the two voltages and ground.

More on achieving a sine wave

Resonant inverters produce sine waves with LC circuits to remove the harmonics from a simple square wave. Typically there are several series- and parallel-resonant LC circuits, each tuned to a different harmonic of the power line frequency. This simplifies the electronics, but the inductors and capacitors tend to be large and heavy. Its high efficiency makes this approach popular in large uninterruptible power supplies in data centers that run the inverter continuously in an "online" mode to avoid any switchover transient when power is lost. (See related: Resonant inverter)

A closely related approach uses a ferroresonant transformer, also known as a constant-voltage transformer, to remove harmonics and to store enough energy to sustain the load for a few AC cycles. This property makes them useful in standby power supplies to eliminate the switchover transient that otherwise occurs during a power failure while the normally idle inverter starts and the mechanical relays are switching to its output.

Enhanced quantization

A proposal suggested in Power Electronics magazine utilizes two voltages as an improvement over the common commercialized technology, which can only apply DC bus voltage in either direction or turn it off. The proposal adds intermediate voltages to the common design. Each cycle sees the following sequence of delivered voltages: v1, v2, v1, 0, −v1, −v2, −v1, 0.

Three-phase inverters

Three-phase inverters are used for variable-frequency drive applications and for high power applications such as HVDC power transmission. A basic three-phase inverter consists of three single-phase inverter switches each connected to one of the three load terminals. For the most basic control scheme, the operation of the three switches is coordinated so that one switch operates at each 60 degree point of the fundamental output waveform. This creates a line-to-line output waveform that has six steps. The six-step waveform has a zero-voltage step between the positive and negative sections of the square-wave such that the harmonics that are multiples of three are eliminated as described above. When carrier-based PWM techniques are applied to six-step waveforms, the basic overall shape, or envelope, of the waveform is retained so that the 3rd harmonic and its multiples are cancelled.

To construct inverters with higher power ratings, two six-step three-phase inverters can be connected in parallel for a higher current rating or in series for a higher voltage rating. In either case, the output waveforms are phase shifted to obtain a 12-step waveform. If additional inverters are combined, an 18-step inverter is obtained with three inverters etc. Although inverters are usually combined for the purpose of achieving increased voltage or current ratings, the quality of the waveform is improved as well.

Size

Compared to other household electric devices, inverters are large in size and volume. In 2014, Google together with IEEE started an open competition named Little Box Challenge, with a prize money of $1,000,000, to build a (much) smaller power inverter.

History

Early inverters

From the late nineteenth century through the middle of the twentieth century, DC-to-AC power conversion was accomplished using rotary converters or motor-generator sets (M-G sets). In the early twentieth century, vacuum tubes and gas-filled tubes began to be used as switches in inverter circuits. The most widely used type of tube was the thyratron.

The origins of electromechanical inverters explain the source of the term inverter. Early AC-to-DC converters used an induction or synchronous AC motor direct-connected to a generator (dynamo) so that the generator's commutator reversed its connections at exactly the right moments to produce DC. A later development is the synchronous converter, in which the motor and generator windings are combined into one armature, with slip rings at one end and a commutator at the other and only one field frame. The result with either is AC-in, DC-out. With an M-G set, the DC can be considered to be separately generated from the AC; with a synchronous converter, in a certain sense it can be considered to be "mechanically rectified AC". Given the right auxiliary and control equipment, an M-G set or rotary converter can be "run backwards", converting DC to AC. Hence an inverter is an inverted converter.

Controlled rectifier inverters

Since early transistors were not available with sufficient voltage and current ratings for most inverter applications, it was the 1957 introduction of the thyristor or silicon-controlled rectifier (SCR) that initiated the transition to solid-state inverter circuits.

The commutation requirements of SCRs are a key consideration in SCR circuit designs. SCRs do not turn off or commutate automatically when the gate control signal is shut off. They only turn off when the forward current is reduced to below the minimum holding current, which varies with each kind of SCR, through some external process. For SCRs connected to an AC power source, commutation occurs naturally every time the polarity of the source voltage reverses. SCRs connected to a DC power source usually require a means of forced commutation that forces the current to zero when commutation is required. The least complicated SCR circuits employ natural commutation rather than forced commutation. With the addition of forced commutation circuits, SCRs have been used in the types of inverter circuits described above.

In applications where inverters transfer power from a DC power source to an AC power source, it is possible to use AC-to-DC controlled rectifier circuits operating in the inversion mode. In the inversion mode, a controlled rectifier circuit operates as a line commutated inverter. This type of operation can be used in HVDC power transmission systems and in regenerative braking operation of motor control systems.

Another type of SCR inverter circuit is the current source input (CSI) inverter. A CSI inverter is the dual of a six-step voltage source inverter. With a current-source inverter, the DC power supply is configured as a current source rather than a voltage source. The inverter SCRs are switched in a six-step sequence to direct the current to a three-phase AC load as a stepped current waveform. CSI inverter commutation methods include load commutation and parallel capacitor commutation. With both methods, the input current regulation assists the commutation. With load commutation, the load is a synchronous motor operated at a leading power factor.

As they have become available in higher voltage and current ratings, semiconductors such as transistors or IGBTs that can be turned off by means of control signals have become the preferred switching components for use in inverter circuits.

Rectifier and inverter pulse numbers

Rectifier circuits are often classified by the number of current pulses that flow to the DC side of the rectifier per cycle of AC input voltage. A single-phase half-wave rectifier is a one-pulse circuit and a single-phase full-wave rectifier is a two-pulse circuit. A three-phase half-wave rectifier is a three-pulse circuit and a three-phase full-wave rectifier is a six-pulse circuit.

With three-phase rectifiers, two or more rectifiers are sometimes connected in series or parallel to obtain higher voltage or current ratings. The rectifier inputs are supplied from special transformers that provide phase shifted outputs. This has the effect of phase multiplication. Six phases are obtained from two transformers, twelve phases from three transformers, and so on. The associated rectifier circuits are 12-pulse rectifiers, 18-pulse rectifiers, and so on...

When controlled rectifier circuits are operated in the inversion mode, they would be classified by pulse number also. Rectifier circuits that have a higher pulse number have reduced harmonic content in the AC input current and reduced ripple in the DC output voltage. In the inversion mode, circuits that have a higher pulse number have lower harmonic content in the AC output voltage waveform.

Other notes

The large switching devices for power transmission applications installed until 1970 predominantly used mercury-arc valves. Modern inverters are usually solid state (static inverters). A modern design method features components arranged in an Hbridge configuration. This design is also quite popular with smaller-scale consumer devices.

See also

- Distributed inverter architecture

- Electric power conversion

- Electronic oscillator

- Power electronics#DC/AC converters (inverters)

- Push–pull converter

- Solid-state transformer

- Space vector modulation

- Switched-mode power supply (SMPS)

- Synchronverter

- Uninterruptible power supply

- Variable-frequency drive

- Z-source inverter

References

- The Authoritative Dictionary of IEEE Standards Terms, Seventh Edition, IEEE Press, 2000,ISBN 0-7381-2601-2, page 588

- "Inverter frequently asked questions". powerstream.com. Retrieved 2020-11-13.

- How to Choose an Inverter for an Independent Energy System, 2001

- ^ The importance of total harmonic distortion, retrieved April 19, 2019

- "E project" (PDF). wpi.edu. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- Stefanos Manias, Power Electronics and Motor Drive Systems, Academic Press, 2016, ISBN 0128118148, page 288-289

- Stefanos Manias, Power Electronics and Motor Drive Systems, Academic Press, 2016, ISBN 0128118148 page 288

- Barnes, Malcolm (2003). Practical variable speed drives and power electronics. Oxford: Newnes. p. 97. ISBN 978-0080473918.

- "Inverter Basics and Selecting the Right Model - Northern Arizona Wind & Sun". windsun.com. Archived from the original on 2013-03-30. Retrieved 2011-08-16.

- Runtime of Power Inverter by batteries Retrieved 2024-3-13

- "Inverter Battery Capacity Calculator & Easy To Follow Formula". InverterBatteries.in. 2020-03-15. Retrieved 2020-07-22.

- "New and Cool: Variable Refrigerant Flow Systems". AIArchitect. American Institute of Architects. 2009-04-10. Retrieved 2013-08-06.

- "Toshiba Science Museum: World's First Residential Inverter Air Conditioner". toshiba-mirai-kagakukan.jp.

- Du, Ruoyang; Robertson, Paul (2017). "Cost Effective Grid-Connected Inverter for a Micro Combined Heat and Power System" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics. 64 (7): 5360–5367. doi:10.1109/TIE.2017.2677340. ISSN 0278-0046. S2CID 1042325.

- Mark (2019-11-27). "What is a Solar Generator & How Does it Work?". Modern Survivalists. Retrieved 2019-12-30.

- Unruh, Roland (Oct 2020). "Evaluation of MMCs for High-Power Low-Voltage DC-Applications in Combination with the Module LLC-Design". 22nd European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications (EPE'20 ECCE Europe). pp. 1–10. doi:10.23919/EPE20ECCEEurope43536.2020.9215687. ISBN 978-9-0758-1536-8. S2CID 222223518.

- Kassakian, John G. (1991). Principles of Power Electronics. Addison-Wesley. pp. 169–193. ISBN 978-0201096897.

- ^ Hahn, James H (August 2006). "Modified Sine-Wave Inverter Enhanced". Electronic Design.

- "MIT open-courseware, Power Electronics, Spring 2007". mit.edu.

- Rodriguez, Jose; et al. (August 2002). "Multilevel Inverters: A Survey of Topologies, Controls, and Applications". IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics. 49 (4): 724–738. doi:10.1109/TIE.2002.801052. hdl:10533/173647.

- "The Little Box Challenge, an open competition to build a smaller power inverter". Archived from the original on 2014-07-23. Retrieved 2014-07-23.

- Owen, Edward L. (January–February 1996). "Origins of the Inverter". IEEE Industry Applications Magazine: History Department. 2 (1): 64–66. doi:10.1109/2943.476602.

- D. R. Grafham; J. C. Hey, eds. (1972). SCR Manual (Fifth ed.). Syracuse, N.Y. USA: General Electric. pp. 236–239.

- Bailu Xiao; Faete Filho; Leon M. Tolbert (2011). "Single-Phase Cascaded H-Bridge Multilevel Inverter with Nonactive Power Compensation for Grid-Connected Photovoltaic Generators" (PDF). web.eecs.utk.edu. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- Andreas Moglestue (2013). "From mercury arc to hybrid breaker: 100 years in power electronics" (PDF). ABB Review. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-03-27. Retrieved 2024-01-10.

Further reading

- Bedford, B. D.; Hoft, R. G.; et al. (1964). Principles of Inverter Circuits. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-471-06134-2.

- Mazda, F. F. (1973). Thyristor Control. New York: Halsted Press Div. of John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-58116-2.

- Ulrich Nicolai, Tobias Reimann, Jürgen Petzoldt, Josef Lutz: Application Handbook: IGBT and MOSFET Power Modules, 1. Edition, ISLE Verlag, 1998, ISBN 3-932633-24-5 PDF-Version

- Application Manual: Power Semiconductors, Arendt Wintrich, Ulrich Nicolai, Werner Tursky, Tobias Reimann. SEMIKRON International GmbH. 2011. ISBN 978-3-938843-66-6.

External links

- Three-level PWM Floating H-bridge Sinewave Power Inverter for High-voltage and High-efficiency Applications, Vratislav MICHAL, September 2015 IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics 1(6):885–8993 DOI:10.1109/TPEL.2015.2477246 (example of a three-level PWM single-phase full-bridge power inverter design)

| Electric machines | |

|---|---|

| |

| Components and accessories | |

| Generators | |

| Motors | |

| Motor controllers | |

| History, education, recreational use | |

| Experimental, futuristic | |

| Related topics | |

| People | |