Pharmaceutical compound

Skeletal formula of dopamine Skeletal formula of dopamine | |

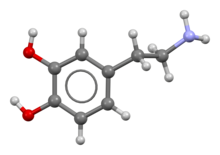

Ball-and-stick model of the dopamine molecule as found in solution. In the solid state, dopamine adopts a zwitterionic form. Ball-and-stick model of the dopamine molecule as found in solution. In the solid state, dopamine adopts a zwitterionic form. | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names |

|

| Physiological data | |

| Source tissues | Substantia nigra; ventral tegmental area; many others |

| Target tissues | System-wide |

| Receptors | D1, D2, D3, D4, D5, TAAR1 |

| Agonists | Direct: apomorphine, bromocriptine Indirect: cocaine, amphetamine, methylphenidate |

| Antagonists | Neuroleptics, metoclopramide, domperidone |

| Precursor | Phenylalanine, tyrosine, and L-DOPA |

| Biosynthesis | DOPA decarboxylase |

| Metabolism | MAO, COMT |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.101 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C8H11NO2 |

| Molar mass | 153.181 g·mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Dopamine (DA, a contraction of 3,4-dihydroxyphenethylamine) is a neuromodulatory molecule that plays several important roles in cells. It is an organic chemical of the catecholamine and phenethylamine families. Dopamine constitutes about 80% of the catecholamine content in the brain. It is an amine synthesized by removing a carboxyl group from a molecule of its precursor chemical, L-DOPA, which is synthesized in the brain and kidneys. Dopamine is also synthesized in plants and most animals. In the brain, dopamine functions as a neurotransmitter—a chemical released by neurons (nerve cells) to send signals to other nerve cells. Neurotransmitters are synthesized in specific regions of the brain but affect many regions systemically. The brain includes several distinct dopamine pathways, one of which plays a major role in the motivational component of reward-motivated behavior. The anticipation of most types of rewards increases the level of dopamine in the brain, and many addictive drugs increase dopamine release or block its reuptake into neurons following release. Other brain dopamine pathways are involved in motor control and in controlling the release of various hormones. These pathways and cell groups form a dopamine system which is neuromodulatory.

In popular culture and media, dopamine is often portrayed as the main chemical of pleasure, but the current opinion in pharmacology is that dopamine instead confers motivational salience; in other words, dopamine signals the perceived motivational prominence (i.e., the desirability or aversiveness) of an outcome, which in turn propels the organism's behavior toward or away from achieving that outcome.

Outside the central nervous system, dopamine functions primarily as a local paracrine messenger. In blood vessels, it inhibits norepinephrine release and acts as a vasodilator; in the kidneys, it increases sodium excretion and urine output; in the pancreas, it reduces insulin production; in the digestive system, it reduces gastrointestinal motility and protects intestinal mucosa; and in the immune system, it reduces the activity of lymphocytes. With the exception of the blood vessels, dopamine in each of these peripheral systems is synthesized locally and exerts its effects near the cells that release it.

Several important diseases of the nervous system are associated with dysfunctions of the dopamine system, and some of the key medications used to treat them work by altering the effects of dopamine. Parkinson's disease, a degenerative condition causing tremor and motor impairment, is caused by a loss of dopamine-secreting neurons in an area of the midbrain called the substantia nigra. Its metabolic precursor L-DOPA can be manufactured; Levodopa, a pure form of L-DOPA, is the most widely used treatment for Parkinson's. There is evidence that schizophrenia involves altered levels of dopamine activity, and most antipsychotic drugs used to treat this are dopamine antagonists which reduce dopamine activity. Similar dopamine antagonist drugs are also some of the most effective anti-nausea agents. Restless legs syndrome and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are associated with decreased dopamine activity. Dopaminergic stimulants can be addictive in high doses, but some are used at lower doses to treat ADHD. Dopamine itself is available as a manufactured medication for intravenous injection. It is useful in the treatment of severe heart failure or cardiogenic shock. In newborn babies it may be used for hypotension and septic shock.

Structure

A dopamine molecule consists of a catechol structure (a benzene ring with two hydroxyl side groups) with one amine group attached via an ethyl chain. As such, dopamine is the simplest possible catecholamine, a family that also includes the neurotransmitters norepinephrine and epinephrine. The presence of a benzene ring with this amine attachment makes it a substituted phenethylamine, a family that includes numerous psychoactive drugs.

Like most amines, dopamine is an organic base. As a base, it is generally protonated in acidic environments (in an acid-base reaction). The protonated form is highly water-soluble and relatively stable, but can become oxidized if exposed to oxygen or other oxidants. In basic environments, dopamine is not protonated. In this free base form, it is less water-soluble and also more highly reactive. Because of the increased stability and water-solubility of the protonated form, dopamine is supplied for chemical or pharmaceutical use as dopamine hydrochloride—that is, the hydrochloride salt that is created when dopamine is combined with hydrochloric acid. In dry form, dopamine hydrochloride is a fine powder which is white to yellow in color.

Dopamine structure

Dopamine structure Phenethylamine structure

Phenethylamine structure Catechol structure

Catechol structure

Biochemistry

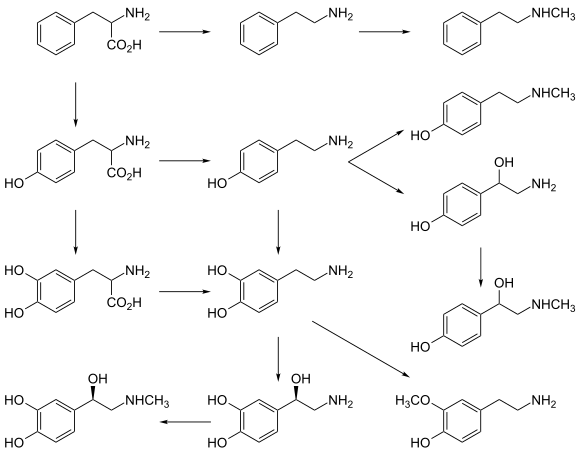

Biosynthetic pathways for catecholamines and trace amines in the human brain

L-Phenylalanine

L-Tyrosine

L-DOPA

Epinephrine

Phenethylamine

p-Tyramine

Dopamine

Norepinephrine

N-Methylphenethylamine

N-Methyltyramine

p-Octopamine

Synephrine

3-Methoxytyramine

AADC

AADC

AADC

primary

L-Phenylalanine

L-Tyrosine

L-DOPA

Epinephrine

Phenethylamine

p-Tyramine

Dopamine

Norepinephrine

N-Methylphenethylamine

N-Methyltyramine

p-Octopamine

Synephrine

3-Methoxytyramine

AADC

AADC

AADC

primarypathway PNMT PNMT PNMT PNMT AAAH AAAH brain CYP2D6 minor pathway COMT DBH DBH |

Synthesis

Dopamine is synthesized in a restricted set of cell types, mainly neurons and cells in the medulla of the adrenal glands. The primary and minor metabolic pathways respectively are:

- Primary: L-Phenylalanine → L-Tyrosine → L-DOPA → Dopamine

- Minor: L-Phenylalanine → L-Tyrosine → p-Tyramine → Dopamine

- Minor: L-Phenylalanine → m-Tyrosine → m-Tyramine → Dopamine

The direct precursor of dopamine, L-DOPA, can be synthesized indirectly from the essential amino acid phenylalanine or directly from the non-essential amino acid tyrosine. These amino acids are found in nearly every protein and so are readily available in food, with tyrosine being the most common. Although dopamine is also found in many types of food, it is incapable of crossing the blood–brain barrier that surrounds and protects the brain. It must therefore be synthesized inside the brain to perform its neuronal activity.

L-Phenylalanine is converted into L-tyrosine by the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase, with molecular oxygen (O2) and tetrahydrobiopterin as cofactors. L-Tyrosine is converted into L-DOPA by the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase, with tetrahydrobiopterin, O2, and iron (Fe) as cofactors. L-DOPA is converted into dopamine by the enzyme aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (also known as DOPA decarboxylase), with pyridoxal phosphate as the cofactor.

Dopamine itself is used as precursor in the synthesis of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine and epinephrine. Dopamine is converted into norepinephrine by the enzyme dopamine β-hydroxylase, with O2 and L-ascorbic acid as cofactors. Norepinephrine is converted into epinephrine by the enzyme phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase with S-adenosyl-L-methionine as the cofactor.

Some of the cofactors also require their own synthesis. Deficiency in any required amino acid or cofactor can impair the synthesis of dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine.

Degradation

Dopamine is broken down into inactive metabolites by a set of enzymes—monoamine oxidase (MAO), catechol-O-methyl transferase (COMT), and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), acting in sequence. Both isoforms of monoamine oxidase, MAO-A and MAO-B, effectively metabolize dopamine. Different breakdown pathways exist but the main end-product is homovanillic acid (HVA), which has no known biological activity. From the bloodstream, homovanillic acid is filtered out by the kidneys and then excreted in the urine. The two primary metabolic routes that convert dopamine into HVA are:

- Dopamine → DOPAL → DOPAC → HVA – catalyzed by MAO, ALDH, and COMT respectively

- Dopamine → 3-Methoxytyramine → HVA – catalyzed by COMT and MAO+ALDH respectively

In clinical research on schizophrenia, measurements of homovanillic acid in plasma have been used to estimate levels of dopamine activity in the brain. A difficulty in this approach however, is separating the high level of plasma homovanillic acid contributed by the metabolism of norepinephrine.

Although dopamine is normally broken down by an oxidoreductase enzyme, it is also susceptible to oxidation by direct reaction with oxygen, yielding quinones plus various free radicals as products. The rate of oxidation can be increased by the presence of ferric iron or other factors. Quinones and free radicals produced by autoxidation of dopamine can poison cells, and there is evidence that this mechanism may contribute to the cell loss that occurs in Parkinson's disease and other conditions.

Functions

Cellular effects

Main articles: Dopamine receptor and TAAR1| Family | Receptor | Gene | Type | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1-like | D1 | DRD1 | Gs-coupled. | Increase intracellular levels of cAMP by activating adenylate cyclase. |

| D5 | DRD5 | |||

| D2-like | D2 | DRD2 | Gi-coupled. | Decrease intracellular levels of cAMP by inhibiting adenylate cyclase. |

| D3 | DRD3 | |||

| D4 | DRD4 | |||

| TAAR | TAAR1 | TAAR1 | Gs-coupled. Gq-coupled. |

Increase intracellular levels of cAMP and intracellular calcium concentration. |

Dopamine exerts its effects by binding to and activating cell surface receptors. In humans, dopamine has a high binding affinity at dopamine receptors and human trace amine-associated receptor 1 (hTAAR1). In mammals, five subtypes of dopamine receptors have been identified, labeled from D1 to D5. All of them function as metabotropic, G protein-coupled receptors, meaning that they exert their effects via a complex second messenger system. These receptors can be divided into two families, known as D1-like and D2-like. For receptors located on neurons in the nervous system, the ultimate effect of D1-like activation (D1 and D5) can be excitation (via opening of sodium channels) or inhibition (via opening of potassium channels); the ultimate effect of D2-like activation (D2, D3, and D4) is usually inhibition of the target neuron. Consequently, it is incorrect to describe dopamine itself as either excitatory or inhibitory: its effect on a target neuron depends on which types of receptors are present on the membrane of that neuron and on the internal responses of that neuron to the second messenger cAMP. D1 receptors are the most numerous dopamine receptors in the human nervous system; D2 receptors are next; D3, D4, and D5 receptors are present at significantly lower levels.

Storage, release, and reuptake

TH: tyrosine hydroxylase

DOPA: L-DOPA

DAT: dopamine transporter

DDC: DOPA decarboxylase

VMAT: vesicular monoamine transporter 2

MAO: Monoamine oxidase

COMT: Catechol-O-methyl transferase

HVA: Homovanillic acid

Inside the brain, dopamine functions as a neurotransmitter and neuromodulator, and is controlled by a set of mechanisms common to all monoamine neurotransmitters. After synthesis, dopamine is transported from the cytosol into secretory vesicles, including synaptic vesicles, small and large dense core vesicles by a solute carrier—a vesicular monoamine transporter, VMAT2. Dopamine is stored in these vesicles until it is ejected into the synaptic cleft. In most cases, the release of dopamine occurs through a process called exocytosis which is caused by action potentials, but it can also be caused by the activity of an intracellular trace amine-associated receptor, TAAR1. TAAR1 is a high-affinity receptor for dopamine, trace amines, and certain substituted amphetamines that is located along membranes in the intracellular milieu of the presynaptic cell; activation of the receptor can regulate dopamine signaling by inducing dopamine reuptake inhibition and efflux as well as by inhibiting neuronal firing through a diverse set of mechanisms.

Once in the synapse, dopamine binds to and activates dopamine receptors. These can be postsynaptic dopamine receptors, which are located on dendrites (the postsynaptic neuron), or presynaptic autoreceptors (e.g., the D2sh and presynaptic D3 receptors), which are located on the membrane of an axon terminal (the presynaptic neuron). After the postsynaptic neuron elicits an action potential, dopamine molecules quickly become unbound from their receptors. They are then absorbed back into the presynaptic cell, via reuptake mediated either by the dopamine transporter or by the plasma membrane monoamine transporter. Once back in the cytosol, dopamine can either be broken down by a monoamine oxidase or repackaged into vesicles by VMAT2, making it available for future release.

In the brain the level of extracellular dopamine is modulated by two mechanisms: phasic and tonic transmission. Phasic dopamine release, like most neurotransmitter release in the nervous system, is driven directly by action potentials in the dopamine-containing cells. Tonic dopamine transmission occurs when small amounts of dopamine are released without being preceded by presynaptic action potentials. Tonic transmission is regulated by a variety of factors, including the activity of other neurons and neurotransmitter reuptake.

Central nervous system

Main articles: Dopaminergic cell groups and Dopaminergic pathways See also: Hypothalamic–pituitary–prolactin axis

Inside the brain, dopamine plays important roles in executive functions, motor control, motivation, arousal, reinforcement, and reward, as well as lower-level functions including lactation, sexual gratification, and nausea. The dopaminergic cell groups and pathways make up the dopamine system which is neuromodulatory.

Dopaminergic neurons (dopamine-producing nerve cells) are comparatively few in number—a total of around 400,000 in the human brain—and their cell bodies are confined in groups to a few relatively small brain areas. However their axons project to many other brain areas, and they exert powerful effects on their targets. These dopaminergic cell groups were first mapped in 1964 by Annica Dahlström and Kjell Fuxe, who assigned them labels starting with the letter "A" (for "aminergic"). In their scheme, areas A1 through A7 contain the neurotransmitter norepinephrine, whereas A8 through A14 contain dopamine. The dopaminergic areas they identified are the substantia nigra (groups 8 and 9); the ventral tegmental area (group 10); the posterior hypothalamus (group 11); the arcuate nucleus (group 12); the zona incerta (group 13) and the periventricular nucleus (group 14).

The substantia nigra is a small midbrain area that forms a component of the basal ganglia. This has two parts—an input area called the pars reticulata and an output area called the pars compacta. The dopaminergic neurons are found mainly in the pars compacta (cell group A8) and nearby (group A9). In humans, the projection of dopaminergic neurons from the substantia nigra pars compacta to the dorsal striatum, termed the nigrostriatal pathway, plays a significant role in the control of motor function and in learning new motor skills. These neurons are especially vulnerable to damage, and when a large number of them die, the result is a parkinsonian syndrome.

The ventral tegmental area (VTA) is another midbrain area. The most prominent group of VTA dopaminergic neurons projects to the prefrontal cortex via the mesocortical pathway and another smaller group projects to the nucleus accumbens via the mesolimbic pathway. Together, these two pathways are collectively termed the mesocorticolimbic projection. The VTA also sends dopaminergic projections to the amygdala, cingulate gyrus, hippocampus, and olfactory bulb. Mesocorticolimbic neurons play a central role in reward and other aspects of motivation. Accumulating literature shows that dopamine also plays a crucial role in aversive learning through its effects on a number of brain regions.

The posterior hypothalamus has dopamine neurons that project to the spinal cord, but their function is not well established. There is some evidence that pathology in this area plays a role in restless legs syndrome, a condition in which people have difficulty sleeping due to an overwhelming compulsion to constantly move parts of the body, especially the legs.

The arcuate nucleus and the periventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus have dopamine neurons that form an important projection—the tuberoinfundibular pathway which goes to the pituitary gland, where it influences the secretion of the hormone prolactin. Dopamine is the primary neuroendocrine inhibitor of the secretion of prolactin from the anterior pituitary gland. Dopamine produced by neurons in the arcuate nucleus is secreted into the hypophyseal portal system of the median eminence, which supplies the pituitary gland. The prolactin cells that produce prolactin, in the absence of dopamine, secrete prolactin continuously; dopamine inhibits this secretion.

The zona incerta, grouped between the arcuate and periventricular nuclei, projects to several areas of the hypothalamus, and participates in the control of gonadotropin-releasing hormone, which is necessary to activate the development of the male and female reproductive systems, following puberty.

An additional group of dopamine-secreting neurons is found in the retina of the eye. These neurons are amacrine cells, meaning that they have no axons. They release dopamine into the extracellular medium, and are specifically active during daylight hours, becoming silent at night. This retinal dopamine acts to enhance the activity of cone cells in the retina while suppressing rod cells—the result is to increase sensitivity to color and contrast during bright light conditions, at the cost of reduced sensitivity when the light is dim.

Basal ganglia

The largest and most important sources of dopamine in the vertebrate brain are the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area. Both structures are components of the midbrain, closely related to each other and functionally similar in many respects. The largest component of the basal ganglia is the striatum. The substantia nigra sends a dopaminergic projection to the dorsal striatum, while the ventral tegmental area sends a similar type of dopaminergic projection to the ventral striatum.

Progress in understanding the functions of the basal ganglia has been slow. The most popular hypotheses, broadly stated, propose that the basal ganglia play a central role in action selection. The action selection theory in its simplest form proposes that when a person or animal is in a situation where several behaviors are possible, activity in the basal ganglia determines which of them is executed, by releasing that response from inhibition while continuing to inhibit other motor systems that if activated would generate competing behaviors. Thus the basal ganglia, in this concept, are responsible for initiating behaviors, but not for determining the details of how they are carried out. In other words, they essentially form a decision-making system.

The basal ganglia can be divided into several sectors, and each is involved in controlling particular types of actions. The ventral sector of the basal ganglia (containing the ventral striatum and ventral tegmental area) operates at the highest level of the hierarchy, selecting actions at the whole-organism level. The dorsal sectors (containing the dorsal striatum and substantia nigra) operate at lower levels, selecting the specific muscles and movements that are used to implement a given behavior pattern.

Dopamine contributes to the action selection process in at least two important ways. First, it sets the "threshold" for initiating actions. The higher the level of dopamine activity, the lower the impetus required to evoke a given behavior. As a consequence, high levels of dopamine lead to high levels of motor activity and impulsive behavior; low levels of dopamine lead to torpor and slowed reactions. Parkinson's disease, in which dopamine levels in the substantia nigra circuit are greatly reduced, is characterized by stiffness and difficulty initiating movement—however, when people with the disease are confronted with strong stimuli such as a serious threat, their reactions can be as vigorous as those of a healthy person. In the opposite direction, drugs that increase dopamine release, such as cocaine or amphetamine, can produce heightened levels of activity, including, at the extreme, psychomotor agitation and stereotyped movements.

The second important effect of dopamine is as a "teaching" signal. When an action is followed by an increase in dopamine activity, the basal ganglia circuit is altered in a way that makes the same response easier to evoke when similar situations arise in the future. This is a form of operant conditioning, in which dopamine plays the role of a reward signal.

Reward

In the language used to discuss the reward system, reward is the attractive and motivational property of a stimulus that induces appetitive behavior (also known as approach behavior) and consummatory behavior. A rewarding stimulus is one that can induce the organism to approach it and choose to consume it. Pleasure, learning (e.g., classical and operant conditioning), and approach behavior are the three main functions of reward. As an aspect of reward, pleasure provides a definition of reward; however, while all pleasurable stimuli are rewarding, not all rewarding stimuli are pleasurable (e.g., extrinsic rewards like money). The motivational or desirable aspect of rewarding stimuli is reflected by the approach behavior that they induce, whereas the pleasure from intrinsic rewards results from consuming them after acquiring them. A neuropsychological model which distinguishes these two components of an intrinsically rewarding stimulus is the incentive salience model, where "wanting" or desire (less commonly, "seeking") corresponds to appetitive or approach behavior while "liking" or pleasure corresponds to consummatory behavior. In human drug addicts, "wanting" becomes dissociated with "liking" as the desire to use an addictive drug increases, while the pleasure obtained from consuming it decreases due to drug tolerance.

Within the brain, dopamine functions partly as a global reward signal. An initial dopamine response to a rewarding stimulus encodes information about the salience, value, and context of a reward. In the context of reward-related learning, dopamine also functions as a reward prediction error signal, that is, the degree to which the value of a reward is unexpected. According to this hypothesis proposed by Montague, Dayan, and Sejnowski, rewards that are expected do not produce a second phasic dopamine response in certain dopaminergic cells, but rewards that are unexpected, or greater than expected, produce a short-lasting increase in synaptic dopamine, whereas the omission of an expected reward actually causes dopamine release to drop below its background level. The "prediction error" hypothesis has drawn particular interest from computational neuroscientists, because an influential computational-learning method known as temporal difference learning makes heavy use of a signal that encodes prediction error. This confluence of theory and data has led to a fertile interaction between neuroscientists and computer scientists interested in machine learning.

Evidence from microelectrode recordings from the brains of animals shows that dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and substantia nigra are strongly activated by a wide variety of rewarding events. These reward-responsive dopamine neurons in the VTA and substantia nigra are crucial for reward-related cognition and serve as the central component of the reward system. The function of dopamine varies in each axonal projection from the VTA and substantia nigra; for example, the VTA–nucleus accumbens shell projection assigns incentive salience ("want") to rewarding stimuli and its associated cues, the VTA–prefrontal cortex projection updates the value of different goals in accordance with their incentive salience, the VTA–amygdala and VTA–hippocampus projections mediate the consolidation of reward-related memories, and both the VTA–nucleus accumbens core and substantia nigra–dorsal striatum pathways are involved in learning motor responses that facilitate the acquisition of rewarding stimuli. Some activity within the VTA dopaminergic projections appears to be associated with reward prediction as well.

Pleasure

While dopamine has a central role in causing "wanting," associated with the appetitive or approach behavioral responses to rewarding stimuli, detailed studies have shown that dopamine cannot simply be equated with hedonic "liking" or pleasure, as reflected in the consummatory behavioral response. Dopamine neurotransmission is involved in some but not all aspects of pleasure-related cognition, since pleasure centers have been identified both within the dopamine system (i.e., nucleus accumbens shell) and outside the dopamine system (i.e., ventral pallidum and parabrachial nucleus). For example, direct electrical stimulation of dopamine pathways, using electrodes implanted in the brain, is experienced as pleasurable, and many types of animals are willing to work to obtain it. Antipsychotic drugs reduce dopamine levels and tend to cause anhedonia, a diminished ability to experience pleasure. Many types of pleasurable experiences—such as sexual intercourse, eating, and playing video games—increase dopamine release. All addictive drugs directly or indirectly affect dopamine neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens; these drugs increase drug "wanting", leading to compulsive drug use, when repeatedly taken in high doses, presumably through the sensitization of incentive-salience. Drugs that increase synaptic dopamine concentrations include psychostimulants such as methamphetamine and cocaine. These produce increases in "wanting" behaviors, but do not greatly alter expressions of pleasure or change levels of satiation. However, opiate drugs such as heroin and morphine produce increases in expressions of "liking" and "wanting" behaviors. Moreover, animals in which the ventral tegmental dopamine system has been rendered inactive do not seek food, and will starve to death if left to themselves, but if food is placed in their mouths they will consume it and show expressions indicative of pleasure.

A clinical study from January 2019 that assessed the effect of a dopamine precursor (levodopa), dopamine antagonist (risperidone), and a placebo on reward responses to music – including the degree of pleasure experienced during musical chills, as measured by changes in electrodermal activity as well as subjective ratings – found that the manipulation of dopamine neurotransmission bidirectionally regulates pleasure cognition (specifically, the hedonic impact of music) in human subjects. This research demonstrated that increased dopamine neurotransmission acts as a sine qua non condition for pleasurable hedonic reactions to music in humans.

A study published in Nature in 1998 found evidence that playing video games releases dopamine in the human striatum. This dopamine is associated with learning, behavior reinforcement, attention, and sensorimotor integration. Researchers used positron emission tomography scans and C-labelled raclopride to track dopamine levels in the brain during goal-directed motor tasks and found that dopamine release was positively correlated with task performance and was greatest in the ventral striatum. This was the first study to demonstrate the behavioral conditions under which dopamine is released in humans. It highlights the ability of positron emission tomography to detect neurotransmitter fluxes during changes in behavior. According to research, potentially problematic video game use is related to personality traits such as low self-esteem and low self-efficacy, anxiety, aggression, and clinical symptoms of depression and anxiety disorders. Additionally, the reasons individuals play video games vary and may include coping, socialization, and personal satisfaction. The DSM-5 defines Internet Gaming Disorder as a mental disorder closely related to Gambling Disorder. This has been supported by some researchers but has also caused controversy.

Outside the central nervous system

Dopamine does not cross the blood–brain barrier, so its synthesis and functions in peripheral areas are to a large degree independent of its synthesis and functions in the brain. A substantial amount of dopamine circulates in the bloodstream, but its functions there are not entirely clear. Dopamine is found in blood plasma at levels comparable to those of epinephrine, but in humans, over 95% of the dopamine in the plasma is in the form of dopamine sulfate, a conjugate produced by the enzyme sulfotransferase 1A3/1A4 acting on free dopamine. The bulk of this dopamine sulfate is produced in the mesenteric organs. The production of dopamine sulfate is thought to be a mechanism for detoxifying dopamine that is ingested as food or produced by the digestive process—levels in the plasma typically rise more than fifty-fold after a meal. Dopamine sulfate has no known biological functions and is excreted in urine.

The relatively small quantity of unconjugated dopamine in the bloodstream may be produced by the sympathetic nervous system, the digestive system, or possibly other organs. It may act on dopamine receptors in peripheral tissues, or be metabolized, or be converted to norepinephrine by the enzyme dopamine beta hydroxylase, which is released into the bloodstream by the adrenal medulla. Some dopamine receptors are located in the walls of arteries, where they act as a vasodilator and an inhibitor of norepinephrine release from postganglionic sympathetic nerves terminals (dopamine can inhibit norepinephrine release by acting on presynaptic dopamine receptors, and also on presynaptic α-1 receptors, like norepinephrine itself). These responses might be activated by dopamine released from the carotid body under conditions of low oxygen, but whether arterial dopamine receptors perform other biologically useful functions is not known.

Beyond its role in modulating blood flow, there are several peripheral systems in which dopamine circulates within a limited area and performs an exocrine or paracrine function. The peripheral systems in which dopamine plays an important role include the immune system, the kidneys and the pancreas.

Immune system

In the immune system dopamine acts upon receptors present on immune cells, especially lymphocytes. Dopamine can also affect immune cells in the spleen, bone marrow, and circulatory system. In addition, dopamine can be synthesized and released by immune cells themselves. The main effect of dopamine on lymphocytes is to reduce their activation level. The functional significance of this system is unclear, but it affords a possible route for interactions between the nervous system and immune system, and may be relevant to some autoimmune disorders.

Kidneys

The renal dopaminergic system is located in the cells of the nephron in the kidney, where all subtypes of dopamine receptors are present. Dopamine is also synthesized there, by tubule cells, and discharged into the tubular fluid. Its actions include increasing the blood supply to the kidneys, increasing the glomerular filtration rate, and increasing the excretion of sodium in the urine. Hence, defects in renal dopamine function can lead to reduced sodium excretion and consequently result in the development of high blood pressure. There is strong evidence that faults in the production of dopamine or in the receptors can result in a number of pathologies including oxidative stress, edema, and either genetic or essential hypertension. Oxidative stress can itself cause hypertension. Defects in the system can also be caused by genetic factors or high blood pressure.

Pancreas

In the pancreas the role of dopamine is somewhat complex. The pancreas consists of two parts, an exocrine and an endocrine component. The exocrine part synthesizes and secretes digestive enzymes and other substances, including dopamine, into the small intestine. The function of this secreted dopamine after it enters the small intestine is not clearly established—the possibilities include protecting the intestinal mucosa from damage and reducing gastrointestinal motility (the rate at which content moves through the digestive system).

The pancreatic islets make up the endocrine part of the pancreas, and synthesize and secrete hormones including insulin into the bloodstream. There is evidence that the beta cells in the islets that synthesize insulin contain dopamine receptors, and that dopamine acts to reduce the amount of insulin they release. The source of their dopamine input is not clearly established—it may come from dopamine that circulates in the bloodstream and derives from the sympathetic nervous system, or it may be synthesized locally by other types of pancreatic cells.

Medical uses

Main article: Dopamine (medication)

Dopamine as a manufactured medication is sold under the trade names Intropin, Dopastat, and Revimine, among others. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines. It is most commonly used as a stimulant drug in the treatment of severe low blood pressure, slow heart rate, and cardiac arrest. It is especially important in treating these in newborn infants. It is given intravenously. Since the half-life of dopamine in plasma is very short—approximately one minute in adults, two minutes in newborn infants and up to five minutes in preterm infants—it is usually given in a continuous intravenous drip rather than a single injection.

Its effects, depending on dosage, include an increase in sodium excretion by the kidneys, an increase in urine output, an increase in heart rate, and an increase in blood pressure. At low doses it acts through the sympathetic nervous system to increase heart muscle contraction force and heart rate, thereby increasing cardiac output and blood pressure. Higher doses also cause vasoconstriction that further increases blood pressure. Older literature also describes very low doses thought to improve kidney function without other consequences, but recent reviews have concluded that doses at such low levels are not effective and may sometimes be harmful. While some effects result from stimulation of dopamine receptors, the prominent cardiovascular effects result from dopamine acting at α1, β1, and β2 adrenergic receptors.

Side effects of dopamine include negative effects on kidney function and irregular heartbeats. The LD50, or lethal dose which is expected to prove fatal in 50% of the population, has been found to be: 59 mg/kg (mouse; administered intravenously); 95 mg/kg (mouse; administered intraperitoneally); 163 mg/kg (rat; administered intraperitoneally); 79 mg/kg (dog; administered intravenously).

Disease, disorders, and pharmacology

See also: List of dopaminergic drugsThe dopamine system plays a central role in several significant medical conditions, including Parkinson's disease, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, Tourette syndrome, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and addiction. Aside from dopamine itself, there are many other important drugs that act on dopamine systems in various parts of the brain or body. Some are used for medical or recreational purposes, but neurochemists have also developed a variety of research drugs, some of which bind with high affinity to specific types of dopamine receptors and either agonize or antagonize their effects, and many that affect other aspects of dopamine physiology, including dopamine transporter inhibitors, VMAT inhibitors, and enzyme inhibitors.

Aging brain

Main article: Aging brainA number of studies have reported an age-related decline in dopamine synthesis and dopamine receptor density (i.e., the number of receptors) in the brain. This decline has been shown to occur in the striatum and extrastriatal regions. Decreases in the D1, D2, and D3 receptors are well documented. The reduction of dopamine with aging is thought to be responsible for many neurological symptoms that increase in frequency with age, such as decreased arm swing and increased rigidity. Changes in dopamine levels may also cause age-related changes in cognitive flexibility.

Multiple sclerosis

Studies reported that dopamine imbalance influences the fatigue in multiple sclerosis. In patients with multiple sclerosis, dopamine inhibits production of IL-17 and IFN-γ by peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease is an age-related disorder characterized by movement disorders such as stiffness of the body, slowing of movement, and trembling of limbs when they are not in use. In advanced stages it progresses to dementia and eventually death. The main symptoms are caused by the loss of dopamine-secreting cells in the substantia nigra. These dopamine cells are especially vulnerable to damage, and a variety of insults, including encephalitis (as depicted in the book and movie Awakenings), repeated sports-related concussions, and some forms of chemical poisoning such as MPTP, can lead to substantial cell loss, producing a parkinsonian syndrome that is similar in its main features to Parkinson's disease. Most cases of Parkinson's disease, however, are idiopathic, meaning that the cause of cell death cannot be identified.

The most widely used treatment for parkinsonism is administration of L-DOPA, the metabolic precursor for dopamine. L-DOPA is converted to dopamine in the brain and various parts of the body by the enzyme DOPA decarboxylase. L-DOPA is used rather than dopamine itself because, unlike dopamine, it is capable of crossing the blood–brain barrier. It is often co-administered with an enzyme inhibitor of peripheral decarboxylation such as carbidopa or benserazide, to reduce the amount converted to dopamine in the periphery and thereby increase the amount of L-DOPA that enters the brain. When L-DOPA is administered regularly over a long time period, a variety of unpleasant side effects such as dyskinesia often begin to appear; even so, it is considered the best available long-term treatment option for most cases of Parkinson's disease.

L-DOPA treatment cannot restore the dopamine cells that have been lost, but it causes the remaining cells to produce more dopamine, thereby compensating for the loss to at least some degree. In advanced stages the treatment begins to fail because the cell loss is so severe that the remaining ones cannot produce enough dopamine regardless of L-DOPA levels. Other drugs that enhance dopamine function, such as bromocriptine and pergolide, are also sometimes used to treat Parkinsonism, but in most cases L-DOPA appears to give the best trade-off between positive effects and negative side-effects.

Dopaminergic medications that are used to treat Parkinson's disease are sometimes associated with the development of a dopamine dysregulation syndrome, which involves the overuse of dopaminergic medication and medication-induced compulsive engagement in natural rewards like gambling and sexual activity. The latter behaviors are similar to those observed in individuals with a behavioral addiction.

Drug addiction and psychostimulants

Main article: Addiction

Cocaine, substituted amphetamines (including methamphetamine), Adderall, methylphenidate (marketed as Ritalin or Concerta), and other psychostimulants exert their effects primarily or partly by increasing dopamine levels in the brain by a variety of mechanisms. Cocaine and methylphenidate are dopamine transporter blockers or reuptake inhibitors; they non-competitively inhibit dopamine reuptake, resulting in increased dopamine concentrations in the synaptic cleft. Like cocaine, substituted amphetamines and amphetamine also increase the concentration of dopamine in the synaptic cleft, but by different mechanisms.

The effects of psychostimulants include increases in heart rate, body temperature, and sweating; improvements in alertness, attention, and endurance; increases in pleasure produced by rewarding events; but at higher doses agitation, anxiety, or even loss of contact with reality. Drugs in this group can have a high addiction potential, due to their activating effects on the dopamine-mediated reward system in the brain. However some can also be useful, at lower doses, for treating attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and narcolepsy. An important differentiating factor is the onset and duration of action. Cocaine can take effect in seconds if it is injected or inhaled in free base form; the effects last from 5 to 90 minutes. This rapid and brief action makes its effects easily perceived and consequently gives it high addiction potential. Methylphenidate taken in pill form, in contrast, can take two hours to reach peak levels in the bloodstream, and depending on formulation the effects can last for up to 12 hours. These longer acting formulations have the benefit of reducing the potential for abuse, and improving adherence for treatment by using more convenient dosage regimens.

A variety of addictive drugs produce an increase in reward-related dopamine activity. Stimulants such as nicotine, cocaine and methamphetamine promote increased levels of dopamine which appear to be the primary factor in causing addiction. For other addictive drugs such as the opioid heroin, the increased levels of dopamine in the reward system may play only a minor role in addiction. When people addicted to stimulants go through withdrawal, they do not experience the physical suffering associated with alcohol withdrawal or withdrawal from opiates; instead they experience craving, an intense desire for the drug characterized by irritability, restlessness, and other arousal symptoms, brought about by psychological dependence.

The dopamine system plays a crucial role in several aspects of addiction. At the earliest stage, genetic differences that alter the expression of dopamine receptors in the brain can predict whether a person will find stimulants appealing or aversive. Consumption of stimulants produces increases in brain dopamine levels that last from minutes to hours. Finally, the chronic elevation in dopamine that comes with repetitive high-dose stimulant consumption triggers a wide-ranging set of structural changes in the brain that are responsible for the behavioral abnormalities which characterize an addiction. Treatment of stimulant addiction is very difficult, because even if consumption ceases, the craving that comes with psychological withdrawal does not. Even when the craving seems to be extinct, it may re-emerge when faced with stimuli that are associated with the drug, such as friends, locations and situations. Association networks in the brain are greatly interlinked.

Psychosis and antipsychotic drugs

Main article: PsychosisPsychiatrists in the early 1950s discovered that a class of drugs known as typical antipsychotics (also known as major tranquilizers), were often effective at reducing the psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia. The introduction of the first widely used antipsychotic, chlorpromazine (Thorazine), in the 1950s, led to the release of many patients with schizophrenia from institutions in the years that followed. By the 1970s researchers understood that these typical antipsychotics worked as antagonists on the D2 receptors. This realization led to the so-called dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia, which postulates that schizophrenia is largely caused by hyperactivity of brain dopamine systems. The dopamine hypothesis drew additional support from the observation that psychotic symptoms were often intensified by dopamine-enhancing stimulants such as methamphetamine, and that these drugs could also produce psychosis in healthy people if taken in large enough doses. In the following decades other atypical antipsychotics that had fewer serious side effects were developed. Many of these newer drugs do not act directly on dopamine receptors, but instead produce alterations in dopamine activity indirectly. These drugs were also used to treat other psychoses. Antipsychotic drugs have a broadly suppressive effect on most types of active behavior, and particularly reduce the delusional and agitated behavior characteristic of overt psychosis.

Later observations, however, have caused the dopamine hypothesis to lose popularity, at least in its simple original form. For one thing, patients with schizophrenia do not typically show measurably increased levels of brain dopamine activity. Even so, many psychiatrists and neuroscientists continue to believe that schizophrenia involves some sort of dopamine system dysfunction. As the "dopamine hypothesis" has evolved over time, however, the sorts of dysfunctions it postulates have tended to become increasingly subtle and complex.

Psychopharmacologist Stephen M. Stahl suggested in a review of 2018 that in many cases of psychosis, including schizophrenia, three interconnected networks based on dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate – each on its own or in various combinations – contributed to an overexcitation of dopamine D2 receptors in the ventral striatum.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Altered dopamine neurotransmission is implicated in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a condition associated with impaired cognitive control, in turn leading to problems with regulating attention (attentional control), inhibiting behaviors (inhibitory control), and forgetting things or missing details (working memory), among other problems. There are genetic links between dopamine receptors, the dopamine transporter, and ADHD, in addition to links to other neurotransmitter receptors and transporters. The most important relationship between dopamine and ADHD involves the drugs that are used to treat ADHD. Some of the most effective therapeutic agents for ADHD are psychostimulants such as methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta) and amphetamine (Evekeo, Adderall, Dexedrine), drugs that increase both dopamine and norepinephrine levels in the brain. The clinical effects of these psychostimulants in treating ADHD are mediated through the indirect activation of dopamine and norepinephrine receptors, specifically dopamine receptor D1 and adrenoceptor α2, in the prefrontal cortex.

Pain

Dopamine plays a role in pain processing in multiple levels of the central nervous system including the spinal cord, periaqueductal gray, thalamus, basal ganglia, and cingulate cortex. Decreased levels of dopamine have been associated with painful symptoms that frequently occur in Parkinson's disease. Abnormalities in dopaminergic neurotransmission also occur in several painful clinical conditions, including burning mouth syndrome, fibromyalgia, and restless legs syndrome.

Nausea

Nausea and vomiting are largely determined by activity in the area postrema in the medulla of the brainstem, in a region known as the chemoreceptor trigger zone. This area contains a large population of type D2 dopamine receptors. Consequently, drugs that activate D2 receptors have a high potential to cause nausea. This group includes some medications that are administered for Parkinson's disease, as well as other dopamine agonists such as apomorphine. In some cases, D2-receptor antagonists such as metoclopramide are useful as anti-nausea drugs.

Fear and Anxiety

Simultaneous positron emission tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), have shown that the amount of dopamine release is dependent on the strength of conditioned fear response and is linearly coupled to learning-induced activity in the amygdala. Dopamine is generally linked to reward learning, but it also plays a key role in fear learning and extinction by helping to form, store and update fear memories through its interaction with other brain regions like amygdala, ventromedial prefrontal cortex and striatum.

Comparative biology and evolution

Microorganisms

There are no reports of dopamine in archaea, but it has been detected in some types of bacteria and in the protozoan called Tetrahymena. Perhaps more importantly, there are types of bacteria that contain homologs of all the enzymes that animals use to synthesize dopamine. It has been proposed that animals derived their dopamine-synthesizing machinery from bacteria, via horizontal gene transfer that may have occurred relatively late in evolutionary time, perhaps as a result of the symbiotic incorporation of bacteria into eukaryotic cells that gave rise to mitochondria.

Animals

Dopamine is used as a neurotransmitter in most multicellular animals. In sponges there is only a single report of the presence of dopamine, with no indication of its function; however, dopamine has been reported in the nervous systems of many other radially symmetric species, including the cnidarian jellyfish, hydra and some corals. This dates the emergence of dopamine as a neurotransmitter back to the earliest appearance of the nervous system, over 500 million years ago in the Cambrian Period. Dopamine functions as a neurotransmitter in vertebrates, echinoderms, arthropods, molluscs, and several types of worm.

In every type of animal that has been examined, dopamine has been seen to modify motor behavior. In the model organism, nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, it reduces locomotion and increases food-exploratory movements; in flatworms it produces "screw-like" movements; in leeches it inhibits swimming and promotes crawling. Across a wide range of vertebrates, dopamine has an "activating" effect on behavior-switching and response selection, comparable to its effect in mammals.

Dopamine has also consistently been shown to play a role in reward learning, in all animal groups. As in all vertebrates – invertebrates such as roundworms, flatworms, molluscs and common fruit flies can all be trained to repeat an action if it is consistently followed by an increase in dopamine levels. In fruit flies, distinct elements for reward learning suggest a modular structure to the insect reward processing system that broadly parallels that in the mammalian one. For example, dopamine regulates short- and long-term learning in monkeys; in fruit flies, different groups of dopamine neurons mediate reward signals for short- and long-term memories.

It had long been believed that arthropods were an exception to this with dopamine being seen as having an adverse effect. Reward was seen to be mediated instead by octopamine, a neurotransmitter closely related to norepinephrine. More recent studies, however, have shown that dopamine does play a part in reward learning in fruit flies. It has also been found that the rewarding effect of octopamine is due to its activating a set of dopaminergic neurons not previously accessed in the research.

Plants

Many plants, including a variety of food plants, synthesize dopamine to varying degrees. The highest concentrations have been observed in bananas—the fruit pulp of red and yellow bananas contains dopamine at levels of 40 to 50 parts per million by weight. Potatoes, avocados, broccoli, and Brussels sprouts may also contain dopamine at levels of 1 part per million or more; oranges, tomatoes, spinach, beans, and other plants contain measurable concentrations less than 1 part per million. The dopamine in plants is synthesized from the amino acid tyrosine, by biochemical mechanisms similar to those that animals use. It can be metabolized in a variety of ways, producing melanin and a variety of alkaloids as byproducts. The functions of plant catecholamines have not been clearly established, but there is evidence that they play a role in the response to stressors such as bacterial infection, act as growth-promoting factors in some situations, and modify the way that sugars are metabolized. The receptors that mediate these actions have not yet been identified, nor have the intracellular mechanisms that they activate.

Dopamine consumed in food cannot act on the brain, because it cannot cross the blood–brain barrier. However, there are also a variety of plants that contain L-DOPA, the metabolic precursor of dopamine. The highest concentrations are found in the leaves and bean pods of plants of the genus Mucuna, especially in Mucuna pruriens (velvet beans), which have been used as a source for L-DOPA as a drug. Another plant containing substantial amounts of L-DOPA is Vicia faba, the plant that produces fava beans (also known as "broad beans"). The level of L-DOPA in the beans, however, is much lower than in the pod shells and other parts of the plant. The seeds of Cassia and Bauhinia trees also contain substantial amounts of L-DOPA.

In a species of marine green algae Ulvaria obscura, a major component of some algal blooms, dopamine is present in very high concentrations, estimated at 4.4% of dry weight. There is evidence that this dopamine functions as an anti-herbivore defense, reducing consumption by snails and isopods.

As a precursor for melanin

Melanins are a family of dark-pigmented substances found in a wide range of organisms. Chemically they are closely related to dopamine, and there is a type of melanin, known as dopamine-melanin, that can be synthesized by oxidation of dopamine via the enzyme tyrosinase. The melanin that darkens human skin is not of this type: it is synthesized by a pathway that uses L-DOPA as a precursor but not dopamine. However, there is substantial evidence that the neuromelanin that gives a dark color to the brain's substantia nigra is at least in part dopamine-melanin.

Dopamine-derived melanin probably appears in at least some other biological systems as well. Some of the dopamine in plants is likely to be used as a precursor for dopamine-melanin. The complex patterns that appear on butterfly wings, as well as black-and-white stripes on the bodies of insect larvae, are also thought to be caused by spatially structured accumulations of dopamine-melanin.

History and development

Main article: History of catecholamine researchDopamine was first synthesized in 1910 by George Barger and James Ewens at Wellcome Laboratories in London, England and first identified in the human brain by Katharine Montagu in 1957. It was named dopamine because it is a monoamine whose precursor in the Barger-Ewens synthesis is 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (levodopa or L-DOPA). Dopamine's function as a neurotransmitter was first recognized in 1958 by Arvid Carlsson and Nils-Åke Hillarp at the Laboratory for Chemical Pharmacology of the National Heart Institute of Sweden. Carlsson was awarded the 2000 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for showing that dopamine is not only a precursor of norepinephrine (noradrenaline) and epinephrine (adrenaline), but is also itself a neurotransmitter.

Polydopamine

Research motivated by adhesive polyphenolic proteins in mussels led to the discovery in 2007 that a wide variety of materials, if placed in a solution of dopamine at slightly basic pH, will become coated with a layer of polymerized dopamine, often referred to as polydopamine. This polymerized dopamine forms by a spontaneous oxidation reaction, and is formally a type of melanin. Furthermore, dopamine self-polymerization can be used to modulate the mechanical properties of peptide-based gels. Synthesis of polydopamine usually involves reaction of dopamine hydrochloride with Tris as a base in water. The structure of polydopamine is unknown.

Polydopamine coatings can form on objects ranging in size from nanoparticles to large surfaces. Polydopamine layers have chemical properties that have the potential to be extremely useful, and numerous studies have examined their possible applications. At the simplest level, they can be used for protection against damage by light, or to form capsules for drug delivery. At a more sophisticated level, their adhesive properties may make them useful as substrates for biosensors or other biologically active macromolecules.

See also

References

- Cruickshank L, Kennedy AR, Shankland N (2013). "CSD Entry TIRZAX: 5-(2-Ammonioethyl)-2-hydroxyphenolate, Dopamine". Cambridge Structural Database: Access Structures. Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre. doi:10.5517/cc10m9nl.

- Cruickshank L, Kennedy AR, Shankland N (2013). "Tautomeric and ionisation forms of dopamine and tyramine in the solid state". J. Mol. Struct. 1051: 132–36. Bibcode:2013JMoSt1051..132C. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2013.08.002.

- ^ "Dopamine: Biological activity". IUPHAR/BPS guide to pharmacology. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- Berridge KC (April 2007). "The debate over dopamine's role in reward: the case for incentive salience". Psychopharmacology. 191 (3): 391–431. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0578-x. PMID 17072591. S2CID 468204.

- ^ Wise RA, Robble MA (January 2020). "Dopamine and Addiction". Annual Review of Psychology. 71 (1): 79–106. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103337. PMID 31905114. S2CID 210043316.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 147–48, 366–67, 375–76. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

- Baliki MN, Mansour A, Baria AT, Huang L, Berger SE, Fields HL, et al. (October 2013). "Parceling human accumbens into putative core and shell dissociates encoding of values for reward and pain". The Journal of Neuroscience. 33 (41): 16383–93. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1731-13.2013. PMC 3792469. PMID 24107968.

- ^ Wenzel JM, Rauscher NA, Cheer JF, Oleson EB (January 2015). "A role for phasic dopamine release within the nucleus accumbens in encoding aversion: a review of the neurochemical literature". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 6 (1): 16–26. doi:10.1021/cn500255p. PMC 5820768. PMID 25491156.

Thus, fear-evoking stimuli are capable of differentially altering phasic dopamine transmission across NAcc subregions. The authors propose that the observed enhancement in NAcc shell dopamine likely reflects general motivational salience, perhaps due to relief from a CS-induced fear state when the US (foot shock) is not delivered. This reasoning is supported by a report from Budygin and colleagues showing that, in anesthetized rats, the termination of tail pinch results in augmented dopamine release in the shell.

- Puglisi-Allegra S, Ventura R (June 2012). "Prefrontal/accumbal catecholamine system processes high motivational salience". Front. Behav. Neurosci. 6: 31. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2012.00031. PMC 3384081. PMID 22754514.

- Moncrieff J (2008). The myth of the chemical cure. A critique of psychiatric drug treatment. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-230-57432-8.

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Kollins SH, Wigal TL, Newcorn JH, Telang F, et al. (September 2009). "Evaluating dopamine reward pathway in ADHD: clinical implications". JAMA. 302 (10): 1084–91. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1308. PMC 2958516. PMID 19738093.

- "Dopamine infusion" (PDF). Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ "Shock and Hypotension in the Newborn Medication: Alpha/Beta Adrenergic Agonists, Vasodilators, Inotropic agents, Volume Expanders, Antibiotics, Other". emedicine.medscape.com. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- "Dopamine". PubChem. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- "Catecholamine". Britannica. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- "Phenylethylamine". ChemicalLand21.com. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ^ Carter JE, Johnson JH, Baaske DM (1982). "Dopamine Hydrochloride". Analytical Profiles of Drug Substances. 11: 257–72. doi:10.1016/S0099-5428(08)60266-X. ISBN 978-0122608117.

- "Specification Sheet". www.sigmaaldrich.com. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ Broadley KJ (March 2010). "The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 125 (3): 363–375. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. PMID 19948186.

- ^ Lindemann L, Hoener MC (May 2005). "A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 26 (5): 274–281. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.007. PMID 15860375.

- ^ Wang X, Li J, Dong G, Yue J (February 2014). "The endogenous substrates of brain CYP2D". European Journal of Pharmacology. 724: 211–218. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.12.025. PMID 24374199.

- ^ Seeman P (2009). "Chapter 1: Historical overview: Introduction to the dopamine receptors". In Neve K (ed.). The Dopamine Receptors. Springer. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-1-60327-333-6.

- "EC 1.14.16.2 – Tyrosine 3-monooxygenase (Homo sapiens)". BRENDA. Technische Universität Braunschweig. July 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

Substrate: L-phenylalanine + tetrahydrobiopterin + O2

Product: L-tyrosine + 3-hydroxyphenylalanine + dihydropteridine + H2O

Organism: Homo sapiens

Reaction diagram - "EC 4.1.1.28 – Aromatic-L-amino-acid decarboxylase (Homo sapiens)". BRENDA. Technische Universität Braunschweig. July 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

Substrate: m-tyrosine

Product: m-tyramine + CO2

Organism: Homo sapiens

Reaction diagram - ^ Musacchio JM (2013). "Chapter 1: Enzymes involved in the biosynthesis and degradation of catecholamines". In Iverson L (ed.). Biochemistry of Biogenic Amines. Springer. pp. 1–35. ISBN 978-1-4684-3171-1.

- ^ The National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions, ed. (2006). "Symptomatic pharmacological therapy in Parkinson's disease". Parkinson's Disease. London: Royal College of Physicians. pp. 59–100. ISBN 978-1-86016-283-1. Archived from the original on 24 September 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ Eisenhofer G, Kopin IJ, Goldstein DS (September 2004). "Catecholamine metabolism: a contemporary view with implications for physiology and medicine". Pharmacological Reviews. 56 (3): 331–49. doi:10.1124/pr.56.3.1. PMID 15317907. S2CID 12825309.

- Zahoor I, Shafi A, Haq E (December 2018). "Pharmacological Treatment of Parkinson's Disease: Figure 1: [Metabolic pathway of dopamine synthesis...]". In Stoker TB, Greenland JC (eds.). Parkinson's Disease: Pathogenesis and Clinical Aspects . Brisbane (AU): Codon Publications.

- Amin F, Davidson M, Davis KL (1992). "Homovanillic acid measurement in clinical research: a review of methodology". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 18 (1): 123–48. doi:10.1093/schbul/18.1.123. PMID 1553492.

- Amin F, Davidson M, Kahn RS, Schmeidler J, Stern R, Knott PJ, et al. (1995). "Assessment of the central dopaminergic index of plasma HVA in schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 21 (1): 53–66. doi:10.1093/schbul/21.1.53. PMID 7770741.

- Sulzer D, Zecca L (February 2000). "Intraneuronal dopamine-quinone synthesis: a review". Neurotoxicity Research. 1 (3): 181–95. doi:10.1007/BF03033289. PMID 12835101. S2CID 21892355.

- Miyazaki I, Asanuma M (June 2008). "Dopaminergic neuron-specific oxidative stress caused by dopamine itself" (PDF). Acta Medica Okayama. 62 (3): 141–50. doi:10.18926/AMO/30942. PMID 18596830.

- ^ Grandy DK, Miller GM, Li JX (February 2016). ""TAARgeting Addiction" – The Alamo Bears Witness to Another Revolution: An Overview of the Plenary Symposium of the 2015 Behavior, Biology and Chemistry Conference". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 159: 9–16. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.014. PMC 4724540. PMID 26644139.

TAAR1 is a high-affinity receptor for METH/AMPH and DA

- ^ Romanelli RJ, Williams JT, Neve KA (2009). "Chapter 6: Dopamine receptor signalling: intracellular pathways to behavior". In Neve KA (ed.). The Dopamine Receptors. Springer. pp. 137–74. ISBN 978-1-60327-333-6.

- ^ Eiden LE, Schäfer MK, Weihe E, Schütz B (February 2004). "The vesicular amine transporter family (SLC18): amine/proton antiporters required for vesicular accumulation and regulated exocytotic secretion of monoamines and acetylcholine". Pflügers Archiv. 447 (5): 636–40. doi:10.1007/s00424-003-1100-5. PMID 12827358. S2CID 20764857.

- Westerink R (1 February 2006). "Targeting Exocytosis: Ins and Outs of the Modulation of Quantal Dopamine Release". CNS & Neurological Disorders - Drug Targets. 5 (1): 57–77. doi:10.2174/187152706784111597. ISSN 1871-5273. PMID 16613554.

- ^ Miller GM (January 2011). "The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity". Journal of Neurochemistry. 116 (2): 164–76. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. PMC 3005101. PMID 21073468.

- ^ Beaulieu JM, Gainetdinov RR (March 2011). "The physiology, signaling, and pharmacology of dopamine receptors". Pharmacological Reviews. 63 (1): 182–217. doi:10.1124/pr.110.002642. PMID 21303898. S2CID 2545878.

- Torres GE, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG (January 2003). "Plasma membrane monoamine transporters: structure, regulation and function". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 4 (1): 13–25. doi:10.1038/nrn1008. PMID 12511858. S2CID 21545649.

- ^ Rice ME, Patel JC, Cragg SJ (December 2011). "Dopamine release in the basal ganglia". Neuroscience. 198: 112–37. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.08.066. PMC 3357127. PMID 21939738.

- Schultz W (2007). "Multiple dopamine functions at different time courses". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 30: 259–88. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135722. PMID 17600522. S2CID 13503219.

- ^ Björklund A, Dunnett SB (May 2007). "Dopamine neuron systems in the brain: an update". Trends in Neurosciences. 30 (5): 194–202. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.006. PMID 17408759. S2CID 14239716.

- ^ Dahlstroem A, Fuxe K (1964). "Evidence for the existence of monoamine-containing neurons in the central nervous system. I. Demonstration of monoamines in the cell bodies of brain stem neurons". Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 232 (Suppl): 1–55. PMID 14229500.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 6: Widely Projecting Systems: Monoamines, Acetylcholine, and Orexin". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 147–48, 154–57. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

- Christine CW, Aminoff MJ (September 2004). "Clinical differentiation of parkinsonian syndromes: prognostic and therapeutic relevance". The American Journal of Medicine. 117 (6): 412–19. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.032. PMID 15380498.

- Fadok JP, Dickerson TM, Palmiter RD (September 2009). "Dopamine is necessary for cue-dependent fear conditioning". The Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (36): 11089–97. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1616-09.2009. PMC 2759996. PMID 19741115.

- Tang W, Kochubey O, Kintscher M, Schneggenburger R (April 2020). "A VTA to basal amygdala dopamine projection contributes to signal salient somatosensory events during fear learning". The Journal of Neuroscience. 40 (20): JN–RM–1796-19. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1796-19.2020. PMC 7219297. PMID 32277045.

- Jo YS, Heymann G, Zweifel LS (November 2018). "Dopamine Neurons Reflect the Uncertainty in Fear Generalization". Neuron. 100 (4): 916–925.e3. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2018.09.028. PMC 6226002. PMID 30318411.

- ^ Paulus W, Schomburg ED (June 2006). "Dopamine and the spinal cord in restless legs syndrome: does spinal cord physiology reveal a basis for augmentation?". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 10 (3): 185–96. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2006.01.004. PMID 16762808.

- ^ Ben-Jonathan N, Hnasko R (December 2001). "Dopamine as a prolactin (PRL) inhibitor". Endocrine Reviews. 22 (6): 724–63. doi:10.1210/er.22.6.724. PMID 11739329.

- ^ Witkovsky P (January 2004). "Dopamine and retinal function". Documenta Ophthalmologica. Advances in Ophthalmology. 108 (1): 17–40. doi:10.1023/B:DOOP.0000019487.88486.0a. PMID 15104164. S2CID 10354133.

- ^ Fix JD (2008). "Basal Ganglia and the Striatal Motor System". Neuroanatomy (Board Review Series) (4th ed.). Baltimore: Wulters Kluwer & Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 274–81. ISBN 978-0-7817-7245-7.

- ^ Chakravarthy VS, Joseph D, Bapi RS (September 2010). "What do the basal ganglia do? A modeling perspective". Biological Cybernetics. 103 (3): 237–53. doi:10.1007/s00422-010-0401-y. PMID 20644953. S2CID 853119.

- ^ Floresco SB (January 2015). "The nucleus accumbens: an interface between cognition, emotion, and action". Annual Review of Psychology. 66: 25–52. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115159. PMID 25251489. S2CID 28268183.

- ^ Balleine BW, Dezfouli A, Ito M, Doya K (2015). "Hierarchical control of goal-directed action in the cortical–basal ganglia network". Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 5: 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.06.001. S2CID 53148662.

- ^ Jankovic J (April 2008). "Parkinson's disease: clinical features and diagnosis". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 79 (4): 368–76. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.131045. PMID 18344392.

- Pattij T, Vanderschuren LJ (April 2008). "The neuropharmacology of impulsive behaviour". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 29 (4): 192–99. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2008.01.002. PMID 18304658.

- ^ Schultz W (July 2015). "Neuronal Reward and Decision Signals: From Theories to Data". Physiological Reviews. 95 (3): 853–951. doi:10.1152/physrev.00023.2014. PMC 4491543. PMID 26109341.

- ^ Robinson TE, Berridge KC (1993). "The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction". Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews. 18 (3): 247–91. doi:10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. hdl:2027.42/30601. PMID 8401595. S2CID 13471436.

- Wright JS, Panksepp J (2012). "An evolutionary framework to understand foraging, wanting, and desire: the neuropsychology of the SEEKING system". Neuropsychoanalysis. 14 (1): 5–39. doi:10.1080/15294145.2012.10773683. S2CID 145747459. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ Berridge KC, Robinson TE, Aldridge JW (February 2009). "Dissecting components of reward: 'liking', 'wanting', and learning". Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 9 (1): 65–73. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2008.12.014. PMC 2756052. PMID 19162544.

- Montague PR, Dayan P, Sejnowski TJ (March 1996). "A framework for mesencephalic dopamine systems based on predictive Hebbian learning". The Journal of Neuroscience. 16 (5): 1936–47. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01936.1996. PMC 6578666. PMID 8774460.

- Bromberg-Martin ES, Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O (December 2010). "Dopamine in motivational control: rewarding, aversive, and alerting". Neuron. 68 (5): 815–34. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.022. PMC 3032992. PMID 21144997.

- Yager LM, Garcia AF, Wunsch AM, Ferguson SM (August 2015). "The ins and outs of the striatum: Role in drug addiction". Neuroscience. 301: 529–41. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.06.033. PMC 4523218. PMID 26116518.

- ^ Saddoris MP, Cacciapaglia F, Wightman RM, Carelli RM (August 2015). "Differential Dopamine Release Dynamics in the Nucleus Accumbens Core and Shell Reveal Complementary Signals for Error Prediction and Incentive Motivation". The Journal of Neuroscience. 35 (33): 11572–82. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2344-15.2015. PMC 4540796. PMID 26290234.

- Berridge KC, Kringelbach ML (May 2015). "Pleasure systems in the brain". Neuron. 86 (3): 646–64. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.018. PMC 4425246. PMID 25950633.

- ^ Wise RA (1996). "Addictive drugs and brain stimulation reward". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 19: 319–40. doi:10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.001535. PMID 8833446.

- Wise RA (October 2008). "Dopamine and reward: the anhedonia hypothesis 30 years on". Neurotoxicity Research. 14 (2–3): 169–83. doi:10.1007/BF03033808. PMC 3155128. PMID 19073424.

- Arias-Carrión O, Pöppel E (2007). "Dopamine, learning and reward-seeking behavior". Acta Neurobiol Exp. 67 (4): 481–88. doi:10.55782/ane-2007-1664. PMID 18320725.

- Ikemoto S (November 2007). "Dopamine reward circuitry: two projection systems from the ventral midbrain to the nucleus accumbens-olfactory tubercle complex". Brain Research Reviews. 56 (1): 27–78. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.05.004. PMC 2134972. PMID 17574681.

- ^ Ferreri L, Mas-Herrero E, Zatorre RJ, Ripollés P, Gomez-Andres A, Alicart H, et al. (2019). "Dopamine modulates the reward experiences elicited by music". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (9): 3793–98. Bibcode:2019PNAS..116.3793F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1811878116. PMC 6397525. PMID 30670642.

Listening to pleasurable music is often accompanied by measurable bodily reactions such as goose bumps or shivers down the spine, commonly called "chills" or "frissons." ... Overall, our results straightforwardly revealed that pharmacological interventions bidirectionally modulated the reward responses elicited by music. In particular, we found that risperidone impaired participants' ability to experience musical pleasure, whereas levodopa enhanced it. ... Here, in contrast, studying responses to abstract rewards in human subjects, we show that manipulation of dopaminergic transmission affects both the pleasure (i.e., amount of time reporting chills and emotional arousal measured by EDA) and the motivational components of musical reward (money willing to spend). These findings suggest that dopaminergic signaling is a sine qua non condition not only for motivational responses, as has been shown with primary and secondary rewards, but also for hedonic reactions to music. This result supports recent findings showing that dopamine also mediates the perceived pleasantness attained by other types of abstract rewards (37) and challenges previous findings in animal models on primary rewards, such as food (42, 43).

- ^ Goupil L, Aucouturier JJ (February 2019). "Musical pleasure and musical emotions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (9): 3364–66. Bibcode:2019PNAS..116.3364G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1900369116. PMC 6397567. PMID 30770455.

In a pharmacological study published in PNAS, Ferreri et al. (1) present evidence that enhancing or inhibiting dopamine signaling using levodopa or risperidone modulates the pleasure experienced while listening to music. ... In a final salvo to establish not only the correlational but also the causal implication of dopamine in musical pleasure, the authors have turned to directly manipulating dopaminergic signaling in the striatum, first by applying excitatory and inhibitory transcranial magnetic stimulation over their participants' left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, a region known to modulate striatal function (5), and finally, in the current study, by administrating pharmaceutical agents able to alter dopamine synaptic availability (1), both of which influenced perceived pleasure, physiological measures of arousal, and the monetary value assigned to music in the predicted direction. ... While the question of the musical expression of emotion has a long history of investigation, including in PNAS (6), and the 1990s psychophysiological strand of research had already established that musical pleasure could activate the autonomic nervous system (7), the authors' demonstration of the implication of the reward system in musical emotions was taken as inaugural proof that these were veridical emotions whose study has full legitimacy to inform the neurobiology of our everyday cognitive, social, and affective functions (8). Incidentally, this line of work, culminating in the article by Ferreri et al. (1), has plausibly done more to attract research funding for the field of music sciences than any other in this community.

The evidence of Ferreri et al. (1) provides the latest support for a compelling neurobiological model in which musical pleasure arises from the interaction of ancient reward/valuation systems (striatal–limbic–paralimbic) with more phylogenetically advanced perception/predictions systems (temporofrontal). - Koepp MJ, Gunn RN, Lawrence AD, Cunningham VJ, Dagher A, Jones T, et al. (May 1998). "Evidence for striatal dopamine release during a video game". Nature. 393 (6682): 266–268. Bibcode:1998Natur.393..266K. doi:10.1038/30498. PMID 9607763. S2CID 205000565.

- von der Heiden JM, Braun B, Müller KW, Egloff B (2019). "The Association Between Video Gaming and Psychological Functioning". Frontiers in Psychology. 10: 1731. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01731. PMC 6676913. PMID 31402891.

- ^ Missale C, Nash SR, Robinson SW, Jaber M, Caron MG (January 1998). "Dopamine receptors: from structure to function" (PDF). Physiological Reviews. 78 (1): 189–225. doi:10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.189. PMID 9457173. S2CID 223462. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2019.

- ^ Buttarelli FR, Fanciulli A, Pellicano C, Pontieri FE (June 2011). "The dopaminergic system in peripheral blood lymphocytes: from physiology to pharmacology and potential applications to neuropsychiatric disorders". Current Neuropharmacology. 9 (2): 278–88. doi:10.2174/157015911795596612. PMC 3131719. PMID 22131937.

- ^ Sarkar C, Basu B, Chakroborty D, Dasgupta PS, Basu S (May 2010). "The immunoregulatory role of dopamine: an update". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 24 (4): 525–28. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2009.10.015. PMC 2856781. PMID 19896530.