Davis et al. v. The St. Louis Housing Authority is a landmark class-action lawsuit filed in 1952 in Saint Louis, Missouri to challenge explicit racial discrimination in public housing. The decision enjoined the Saint Louis Housing Authority from refusing to rent certain units to qualified African Americans. The case was heard in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri.

Before Davis

The St. Louis Housing Authority is a municipal corporation in St. Louis, Missouri. The Authority is federally funded by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The Authority is tasked, in part, with renting public housing units to qualifying applicants.

Previous to Davis, it was the policy of the Authority to maintain separate facilities for white and black public housing residents. The Court in Davis found that it was the Authority's policy to limit the Clinton Peabody Terrace and John J. Cochran Project to white residents. Similarly, the Court found that the Carr Square Village facilities were limited to black residents.

In the early 1950s, a shortage of units for black residents led some black applicants to apply for admission to buildings reserved for white residents. The Court in Davis found that the plaintiffs were "in desperate need of decent, safe and sanitary housing." Finally the Court found that the St. Louis Housing Authority repeatedly denied black applicants housing where the only units left were in buildings reserved for white residents.

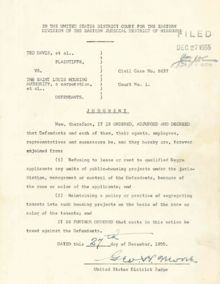

Davis Decision

In the Davis case, Federal Judge Moore found the St. Louis Housing Authority's policy of racial segregation unconstitutional. Judge Moore's order permanently prohibited ("forever enjoined") the Authority from discriminating against qualified housing applicants based on their race. Further, the Authority was prohibited from maintaining policies of racial segregation in their housing units.

Legacy of Davis

Davis is one of the landmark cases that brought an end to public policies of racial segregation and the "separate but equal" doctrine in the United States. Professor of Law Joseph B. Robison wrote in a 1961 volume of the Western Reserve Law Review that, following the Civil War and up to the 1950s, policies of housing discrimination "flourished with almost no legal restraint." Further, due to the "separate but equal" doctrine, Robison notes that cases challenging the constitutionality of these policies were initially unsuccessful in the courts. Finally, Robison notes that the Fifth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments were integral in litigation challenging racial segregation in areas such as housing and education.

An amicus curiae brief on behalf of the plaintiffs in Davis argued that the St. Louis Housing Authority's policies were unconstitutional under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The brief was filed by the Mound City Bar Association of St. Louis and the Kappa Sigma chapter of Phi Beta Sigma fraternity.

Legal Representation in Davis

Davis was a class action lawsuit brought by a group of African American residents of St. Louis, Missouri, all of whom were eligible for public housing through the St. Louis Housing Authority. Plaintiffs in Davis were represented by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), with Frankie Muse Freeman serving as the lead attorney. Freeman went on to a celebrated career as a civil rights attorney.

Defendants in Davis were the City of St. Louis, the St. Louis Housing Authority, and Raymond R. Tucker (Mayor of St. Louis). In addition, state officials involved in the administration of public housing were included as defendants: Arthur A. Blumeyer, Eugene Farrell, Louis C. Justi, Rev. John E. Nance, and Charles L. Farris.

References

- ^ U.S. District Court for the Eastern (St. Louis) Division of the Eastern District of Missouri. 2/28/1887- (1938–1992). Ted Davis, et. al. v. St. Louis Housing Authority. Series: Civil Case Files, 1938 - 1992.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Wright, John A. Sr. (September 18, 2012). African Americans in Downtown St. Louis. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781439614655.

- "Civil Liberties Docket - Vol. I, No. 3 - February, 1956". sunsite.berkeley.edu. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ "The St. Louis Housing Authority". Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- "Civil Liberties Docket - Vol. I, No. 3 - February, 1956". sunsite.berkeley.edu. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ Robison, Joseph B. (1961). "Housing--The Northern Civil Rights Frontier". Western Reserve Law Review. 13 (1): 101–127 – via Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons.

- "NAACP | NAACP Names Frankie Muse Freeman 96th Spingarn Medalist". NAACP. March 22, 2011. Archived from the original on July 6, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- "Civil Rights Pioneer: Frankie Muse Freeman". www.americanbar.org. Retrieved May 31, 2020.