| 大辛庄 | |

| |

| Location | Daxinzhuang, Licheng, Jinan, Shandong, China |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 36°42′40.5″N 117°6′23.4″E / 36.711250°N 117.106500°E / 36.711250; 117.106500 |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 1300 BCE |

| Abandoned | c. 1100 BCE |

| Periods | |

| Site notes | |

| Discovered | 1935 |

| Excavation dates | 1935, 1955, 1984, 2002 |

| Daxinzhuang | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 大辛莊遺址 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 大辛庄遗址 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Daxinzhuang is a Chinese archaeological site located near Daxinzhuang village in Licheng, Jinan, Shandong. Although early occupation in the vicinity has been dated to the Neolithic Longshan (c. 3000 – c. 1900 BCE) and Yueshi culture (c. 1900 – c. 1500 BCE), the site became an urban center during the late Erligang (early 13th century BCE), corresponding to a period of political and military expansion from the heartland of Henan into Shandong. Daxinzhuang became the type site of the Daxinzhuang type, a material culture type shared by other settlements along the Ji River.

It continued to grow during the Anyang period, and became one of the largest Shang settlements outside of the Central Plains. Strategically located along major transportation routes between Henan and Shandong, Daxinzhuang was likely a trade hub for marine goods collected at Bohai Bay, such as pearls, shells, and salt, alongside other resources such as metal and grain. Pottery recovered from the site shows significant influence from the native Yueshi culture, but was gradually assimilated by the beginning of the Anyang period. Also found at the site were a number of oracle bones, including inscribed examples showing a regional variety of the oracle bone script, the earliest known form of Chinese characters.

The settlement was rediscovered in 1933 by Cheeloo University professor Fredrick S. Drake during surveys along the adjacent Qingdao–Jinan railway, and subject to four research reports over the following decade. Shandong University conducted various surveys and test excavations from the 1950s to 1980s. A 1955 test excavation discovered the first Erligang artifacts discovered in Shandong. Larger excavations were conducted in 1984, alongside a regional survey beginning in 2002, which noted later Zhou and Han occupation of the area.

Archaeology

Fredrick S. Drake, a professor at Cheeloo University in Jinan, discovered the Daxinzhuang site in 1935, following archaeological surveys along the Qingdao–Jinan railway. He recorded various features in a series of four research reports published in 1939 and 1940, noting Shang bronzes, bone artifacts, stone tools, and pottery.

Shandong University and the Shandong Provincial Committee of Cultural Resource Management conducted a series of surveys and small-scale excavations at Daxinzhuang from the 1950s to 1980s. A 1955 test excavation found artifacts identified with the Erligang culture (c. 1500 – c. 1400 BCE), the first Erligang artifacts in Shandong. In 1984, a team comprising Shandong University, Jinan Museum, and the Shandong Provincial Institute of Antiquity and Archaeology excavated a variety of structural foundations, graves, wells, a well containing a number of human skulls, and over a hundred oracle bone fragments. A timespan stretching over the late Erligang and Anyang periods was established by Zou Heng (邹衡) in 1964, based off the stylistic attributes of collected ceramics. Periodization was refined over the course of the 1990s with increased stratigraphic data as well as analyses of li tripods and oracle bones from the site. A large scale regional survey begun in 2002 identified limited earlier occupation at the site, dating to the Longshan (c. 3000 – c. 1900 BCE) and Yueshi culture (c. 1900 – c. 1500 BCE), alongside later use during the Zhou and Han dynasties. The following year, a large assemblage of bone tools totaling 218 artifacts was recovered, the largest found at the site.

Site

The Daxinzhuang site is located in a farming field adjacent to the Qingdao–Jinan railway, south of the modern village of Daxinzhuang in Licheng, Jinan. It sits on the southern slopes of the Taiyi Range foothills, slightly under 3 kilometers south of the Xiaoqing River. A number of seasonal streams, draining into the Xiaoqing, run through the area; one of these was dammed by early 20th century railway construction, creating the Xiezigou (蝎子沟; 'Scorpion ditch') which runs through much of the site. Erosion and sediment buildup from farming has filled and widened the Xiezigou, exposing Shang-era sherds and creating a channel about one meter deep, 500 meters long, and 120 meters wide at its thickest. No notable surface fields such as mounds distinguish the site from the surrounding farmland.

History

Daxinzhuang is the type site of a cluster of contemporary sites labeled the Daxinzhuang type, situated along the Ji River valley in northwestern Shandong. Daxinzhuang, alongside Qianzhangda (前掌大) and its associated sites to the south (along the Xue River [zh] in Tengzhou) are the earliest known outposts of the Erligang in Shandong.

The identification of the Erligang with the early Shang dynasty or a centralized state polity remains an active debate in Chinese archaeology. Archaeologists and historians in China generally associate the Erligang as a centralized state corresponding to the Shang dynasty, although critics instead view the culture as loose networks and confederations of local polities. Daxinzhuang may have been an administrative and military outpost, or the result of Erligang's cultural shift eastward. Historian Yuan Guangkuo (袁广阔) described the site as a second-tier settlement of the Erligang, similar to other cities serving as auxiliary capitals or military centers.

The period of eastward expansion began in the 13th century BCE, including into areas occupied by the Yueshi culture. This eastward growth also corresponded to increased political instability and decentralization in the Erligang heartland of Henan. However, Erligang expansion did not proceed further into Shandong beyond Daxinzhuang, possibly due to military resistance from the Dongyi of the Yueshi culture.

Bronzes produced by the Daxinzhuang type are similar to those from Zhengzhou. Ceramics of the subculture are divided into two types, stylistically associated with the Erligang and Yueshi respectively; the latter type became less differentiated over time and ceased to exist as a distinct style during the Anyang period. Due to its proximity to the Ji River, the settlement sat along a major trade route to northern Shandong, procuring grain and metal for the heartland, alongside exotic goods such as pearls and shells.

Daxinzhuang grew as the Erligang transitioned into the Late Shang. Although major Shang cities such as Anyang were over ten times larger, the settlement became one of the largest outside of the Central Plain. The Late Shang period saw the emergence of extensive saltworks along Bohai Bay. Daxinzhuang, due to its advantageous position along the Ji River, likely connected the salt trade to the heartland. This advantageous location also facilitated Shang political control of Eastern Shandong.

Artifacts

Large numbers of bone tools have been recovered from the Daxinzhuang site. These were the result of small-scale, formalized craftsmanship, distinct from the informally produced tools of Guandimiao or the mass-produced tools of Anyang. Small amounts of bone crafts such as hair pins were imported from Anyang, but production in the settlement was largely self-sufficient.

Oracle bones and writing

Alongside Zhengzhou, Zhouyuan, and Anyang, Daxinzhuang is one of four primary sites where Shang-era oracle bones—the first attested examples of written Chinese—have been discovered. While the vast majority of inscriptions have been found within the temple and palace at Anyang, there is considerable evidence for Daxinzhuang having a local variety of the Shang script and its own tradition of literacy.

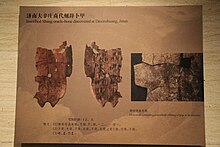

In March 2003, a turtle plastron was found at Daxinzhuang featuring inscriptions in a regional variant of the oracle bone script, likely dating to the Yinxu II or early Yinxu III subperiods (c. 12th century BCE). Like other examples, bones were subject to pyromancy— early forms of Chinese characters were carved into them to ask questions, and answers were interpreted from the cracks formed upon exposing the bones to fire. Initially divided into seven fragments, four of the Daxinzhuang pieces were reconnected by archaeologist Fang Hui (方辉). Analysis of finds at the site since then support the notion that some direct form of Shang royal influence extended as far east as Daxinzhuang, as the inscriptions seem to have been created in a similar context as those in Anyang, which suggests communication between local populations of diviners and scribes. Some aspects of Daxinzhuang inscriptions are unique to the site, including the preparation of materials, the layout of characters on the bones, and occurrence of certain vocabulary and sentence structures.

References

Citations

- ^ Li 2008, p. 70.

- ^ Shandong 2004, p. 29.

- Li 2008, p. 71.

- Li 2008, pp. 72–76.

- ^ Li 2008, p. 76.

- ^ Wang et al. 2022, pp. 2–3.

- Li 2008, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Liu & Chen 2003, pp. 114–115.

- Liu & Chen 2012, pp. 284–285, 363.

- Fang 2013, pp. 474–475.

- ^ Fang 2013, p. 478.

- Yuan 2013, pp. 324–328.

- ^ Liu & Chen 2012, pp. 284–285.

- Liu & Chen 2003, pp. 363–364.

- Wang et al. 2022, pp. 17–18.

- Takashima 2011, pp. 141–143.

- Takashima 2011, p. 171.

- Takashima 2011, pp. 160.

- Thorp 2006, p. 125.

- Takashima 2011, pp. 161–162, 170.

- Takashima 2011, pp. 164–167.

Bibliography

- Li, Min (2008). Conquest, Concord, and Consumption: Becoming Shang in Eastern China (Ph.D thesis). University of Michigan. hdl:2027.42/60866.

- Liu, Li; Chen, Xingcan (2003). State Formation in Early China. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-715-63224-6.

- ———; ——— (2012). The Archaeology of China: From the Late Paleolithic to the Early Bronze Age. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139015301. ISBN 978-0-521-64310-8.

- "Inscribed Oracle Bones of the Shang Period Unearthed from the Daxinzhuang Site in Jinan City". Chinese Archaeology. 4 (1). Oriental Archaeology Research Center, Shandong University; Jinan Municipal Institute of Archaeology. 2004. doi:10.1515/CHAR.2004.4.1.29.

- Takashima, Ken-ichi (2011). "Literacy to the South and the East of Anyang in Shang China: Zhengzhou and Daxinzhuang". In Li, Feng; Branner, David Prager (eds.). Writing and Literacy in Early China: Studies from the Columbia Early China Seminar. Seattle: University of Washington Press. pp. 141–172. ISBN 978-0-295-80450-7. JSTOR j.ctvcwng4z.11.

- Thorp, Robert L. (2006). China in the Early Bronze Age: Shang Civilization. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-812-20361-5. JSTOR j.ctt3fhxmw.

- Underhill, Anne P., ed. (2013). A Companion to Chinese Archaeology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9781118325698. ISBN 978-1-118-32578-0.

- Fang, Hui. "The Eastern Territories of the Shang and Western Zhou: Military Expansion and Cultural Assimilation". In Underhill (2013), pp. 473–493.

- Yuan, Guangkuo. "The Discovery and Study of the Early Shang Culture". In Underhill (2013), pp. 323–342.

- Wang, H.; Campbell, R.; Fang, H.; Hou, Y.; Li, Z. (2022). "Small-scale bone working in a complex economy: The Daxinzhuang worked bone assemblage". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 66. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2022.101411.

External links

- Exhibition of Cultural Relics, Shandong University Museum, including several objects from Daxinzhuang.