In the mathematical field of numerical analysis, De Casteljau's algorithm is a recursive method to evaluate polynomials in Bernstein form or Bézier curves, named after its inventor Paul de Casteljau. De Casteljau's algorithm can also be used to split a single Bézier curve into two Bézier curves at an arbitrary parameter value.

The algorithm is numerically stable when compared to direct evaluation of polynomials. The computational complexity of this algorithm is , where d is the number of dimensions, and n is the number of control points. There exist faster alternatives.

Definition

A Bézier curve (of degree , with control points ) can be written in Bernstein form as follows where is a Bernstein basis polynomial The curve at point can be evaluated with the recurrence relation

Then, the evaluation of at point can be evaluated in operations. The result is given by

Moreover, the Bézier curve can be split at point into two curves with respective control points:

Geometric interpretation

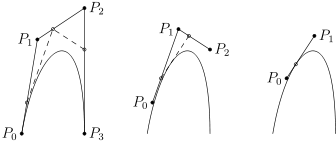

The geometric interpretation of De Casteljau's algorithm is straightforward.

- Consider a Bézier curve with control points . Connecting the consecutive points we create the control polygon of the curve.

- Subdivide now each line segment of this polygon with the ratio and connect the points you get. This way you arrive at the new polygon having one fewer segment.

- Repeat the process until you arrive at the single point – this is the point of the curve corresponding to the parameter .

The following picture shows this process for a cubic Bézier curve:

Note that the intermediate points that were constructed are in fact the control points for two new Bézier curves, both exactly coincident with the old one. This algorithm not only evaluates the curve at , but splits the curve into two pieces at , and provides the equations of the two sub-curves in Bézier form.

The interpretation given above is valid for a nonrational Bézier curve. To evaluate a rational Bézier curve in , we may project the point into ; for example, a curve in three dimensions may have its control points and weights projected to the weighted control points . The algorithm then proceeds as usual, interpolating in . The resulting four-dimensional points may be projected back into three-space with a perspective divide.

In general, operations on a rational curve (or surface) are equivalent to operations on a nonrational curve in a projective space. This representation as the "weighted control points" and weights is often convenient when evaluating rational curves.

Notation

When doing the calculation by hand it is useful to write down the coefficients in a triangle scheme as When choosing a point t0 to evaluate a Bernstein polynomial we can use the two diagonals of the triangle scheme to construct a division of the polynomial into and

Bézier curve

When evaluating a Bézier curve of degree n in 3-dimensional space with n + 1 control points Pi with we split the Bézier curve into three separate equations which we evaluate individually using De Casteljau's algorithm.

Example

We want to evaluate the Bernstein polynomial of degree 2 with the Bernstein coefficients at the point t0.

We start the recursion with and with the second iteration the recursion stops with which is the expected Bernstein polynomial of degree 2.

Implementations

Here are example implementations of De Casteljau's algorithm in various programming languages.

Haskell

deCasteljau :: Double -> -> (Double, Double)

deCasteljau t = b

deCasteljau t coefs = deCasteljau t reduced

where

reduced = zipWith (lerpP t) coefs (tail coefs)

lerpP t (x0, y0) (x1, y1) = (lerp t x0 x1, lerp t y0 y1)

lerp t a b = t * b + (1 - t) * a

Python

def de_casteljau(t: float, coefs: list) -> float:

"""De Casteljau's algorithm."""

beta = coefs.copy() # values in this list are overridden

n = len(beta)

for j in range(1, n):

for k in range(n - j):

beta = beta * (1 - t) + beta * t

return beta

Java

public double deCasteljau(double t, double coefficients) {

double beta = coefficients;

int n = beta.length;

for (int i = 1; i < n; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < (n - i); j++) {

beta = beta * (1 - t) + beta * t;

}

}

return beta;

}

Code Example in JavaScript

The following JavaScript function applies De Casteljau's algorithm to an array of control points or poles as originally named by De Casteljau to reduce them one by one until reaching a point in the curve for a given t between 0 for the first point of the curve and 1 for the last one

function crlPtReduceDeCasteljau(points, t) {

let retArr = ;

while (points.length > 1) {

let midpoints = ;

for (let i = 0; i+1 < points.length; ++i) {

let ax = points;

let ay = points;

let bx = points;

let by = points;

// a * (1-t) + b * t = a + (b - a) * t

midpoints.push([

ax + (bx - ax) * t,

ay + (by - ay) * t,

]);

}

retArr.push (midpoints)

points = midpoints;

}

return retArr;

}

For example,

var poles = , , , ]

crlPtReduceDeCasteljau (poles, .5)

returns the array

, , , ],

, , ],

, ],

],

]

Which points and segments joining them are plotted below

See also

- Bézier curves

- De Boor's algorithm

- Horner scheme to evaluate polynomials in monomial form

- Clenshaw algorithm to evaluate polynomials in Chebyshev form

References

- Delgado, J.; Mainar, E.; Peña, J. M. (2023-10-01). "On the accuracy of de Casteljau-type algorithms and Bernstein representations". Computer Aided Geometric Design. 106: 102243. doi:10.1016/j.cagd.2023.102243. ISSN 0167-8396.

- Woźny, Paweł; Chudy, Filip (2020-01-01). "Linear-time geometric algorithm for evaluating Bézier curves". Computer-Aided Design. 118: 102760. arXiv:1803.06843. doi:10.1016/j.cad.2019.102760. ISSN 0010-4485.

- Fuda, Chiara; Ramanantoanina, Andriamahenina; Hormann, Kai (2024). "A comprehensive comparison of algorithms for evaluating rational Bézier curves". Dolomites Research Notes on Approximation. 17 (9/2024): 56–78. doi:10.14658/PUPJ-DRNA-2024-3-9. ISSN 2035-6803.

- Farin, Gerald E.; Hansford, Dianne (2000). The Essentials of CAGD. Natick, MA: A.K. Peters. ISBN 978-1-56881-123-9.

External links

- Piecewise linear approximation of Bézier curves – description of De Casteljau's algorithm, including a criterion to determine when to stop the recursion

- Bézier Curves and Picasso — Description and illustration of De Casteljau's algorithm applied to cubic Bézier curves.

- de Casteljau's algorithm - Implementation help and interactive demonstration of the algorithm.

, where d is the number of dimensions, and n is the number of control points. There exist faster alternatives.

, where d is the number of dimensions, and n is the number of control points. There exist faster alternatives.

(of degree

(of degree  , with control points

, with control points  ) can be written in Bernstein form as follows

) can be written in Bernstein form as follows

where

where  is a

is a  The curve at point

The curve at point  can be evaluated with the

can be evaluated with the

operations. The result

operations. The result  is given by

is given by

. Connecting the consecutive points we create the control polygon of the curve.

. Connecting the consecutive points we create the control polygon of the curve. and connect the points you get. This way you arrive at the new polygon having one fewer segment.

and connect the points you get. This way you arrive at the new polygon having one fewer segment. .

.

, we may project the point into

, we may project the point into  ; for example, a curve in three dimensions may have its control points

; for example, a curve in three dimensions may have its control points  and weights

and weights  projected to the weighted control points

projected to the weighted control points  . The algorithm then proceeds as usual, interpolating in

. The algorithm then proceeds as usual, interpolating in  . The resulting four-dimensional points may be projected back into three-space with a

. The resulting four-dimensional points may be projected back into three-space with a  When choosing a point t0 to evaluate a Bernstein polynomial we can use the two diagonals of the triangle scheme to construct a division of the polynomial

When choosing a point t0 to evaluate a Bernstein polynomial we can use the two diagonals of the triangle scheme to construct a division of the polynomial

into

into

and

and

with

with

we split the Bézier curve into three separate equations

we split the Bézier curve into three separate equations

which we evaluate individually using De Casteljau's algorithm.

which we evaluate individually using De Casteljau's algorithm.

at the point t0.

at the point t0.

and with the second iteration the recursion stops with

and with the second iteration the recursion stops with

which is the expected Bernstein polynomial of degree 2.

which is the expected Bernstein polynomial of degree 2.