Mathematical proof

The Routh array is a tabular method permitting one to establish the stability of a system using only the coefficients of the characteristic polynomial. Central to the field of control systems design, the Routh–Hurwitz theorem and Routh array emerge by using the Euclidean algorithm and Sturm's theorem in evaluating Cauchy indices.

The Cauchy index

Given the system:

Assuming no roots of  lie on the imaginary axis, and letting

lie on the imaginary axis, and letting

= The number of roots of

= The number of roots of  with negative real parts, and

with negative real parts, and = The number of roots of

= The number of roots of  with positive real parts

with positive real parts

then we have

Expressing  in polar form, we have

in polar form, we have

where

and

from (2) note that

where

Now if the i root of  has a positive real part, then (using the notation y=(RE,IM))

has a positive real part, then (using the notation y=(RE,IM))

and

and

Similarly, if the i root of  has a negative real part,

has a negative real part,

and

and

From (9) to (11) we find that  when the i root of

when the i root of  has a positive real part, and from (12) to (14) we find that

has a positive real part, and from (12) to (14) we find that  when the i root of

when the i root of  has a negative real part. Thus,

has a negative real part. Thus,

So, if we define

then we have the relationship

and combining (3) and (17) gives us

and

and

Therefore, given an equation of  of degree

of degree  we need only evaluate this function

we need only evaluate this function  to determine

to determine  , the number of roots with negative real parts and

, the number of roots with negative real parts and  , the number of roots with positive real parts.

, the number of roots with positive real parts.

|

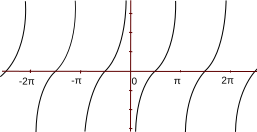

| Figure 1

|

versus versus

|

In accordance with (6) and Figure 1, the graph of  vs

vs  , varying

, varying  over an interval (a,b) where

over an interval (a,b) where  and

and  are integer multiples of

are integer multiples of  , this variation causing the function

, this variation causing the function  to have increased by

to have increased by  , indicates that in the course of travelling from point a to point b,

, indicates that in the course of travelling from point a to point b,  has "jumped" from

has "jumped" from  to

to  one more time than it has jumped from

one more time than it has jumped from  to

to  . Similarly, if we vary

. Similarly, if we vary  over an interval (a,b) this variation causing

over an interval (a,b) this variation causing  to have decreased by

to have decreased by  , where again

, where again  is a multiple of

is a multiple of  at both

at both  and

and  , implies that

, implies that  has jumped from

has jumped from  to

to  one more time than it has jumped from

one more time than it has jumped from  to

to  as

as  was varied over the said interval.

was varied over the said interval.

Thus,  is

is  times the difference between the number of points at which

times the difference between the number of points at which  jumps from

jumps from  to

to  and the number of points at which

and the number of points at which  jumps from

jumps from  to

to  as

as  ranges over the interval

ranges over the interval  provided that at

provided that at  ,

,  is defined.

is defined.

|

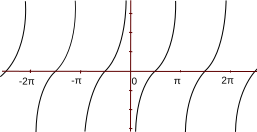

| Figure 2

|

versus versus

|

In the case where the starting point is on an incongruity (i.e.  , i = 0, 1, 2, ...) the ending point will be on an incongruity as well, by equation (17) (since

, i = 0, 1, 2, ...) the ending point will be on an incongruity as well, by equation (17) (since  is an integer and

is an integer and  is an integer,

is an integer,  will be an integer). In this case, we can achieve this same index (difference in positive and negative jumps) by shifting the axes of the tangent function by

will be an integer). In this case, we can achieve this same index (difference in positive and negative jumps) by shifting the axes of the tangent function by  , through adding

, through adding  to

to  . Thus, our index is now fully defined for any combination of coefficients in

. Thus, our index is now fully defined for any combination of coefficients in  by evaluating

by evaluating  over the interval (a,b) =

over the interval (a,b) =  when our starting (and thus ending) point is not an incongruity, and by evaluating

when our starting (and thus ending) point is not an incongruity, and by evaluating

over said interval when our starting point is at an incongruity.

This difference,  , of negative and positive jumping incongruities encountered while traversing

, of negative and positive jumping incongruities encountered while traversing  from

from  to

to  is called the Cauchy Index of the tangent of the phase angle, the phase angle being

is called the Cauchy Index of the tangent of the phase angle, the phase angle being  or

or  , depending as

, depending as  is an integer multiple of

is an integer multiple of  or not.

or not.

The Routh criterion

To derive Routh's criterion, first we'll use a different notation to differentiate between the even and odd terms of  :

:

Now we have:

Therefore, if  is even,

is even,

and if  is odd:

is odd:

Now observe that if  is an odd integer, then by (3)

is an odd integer, then by (3)  is odd. If

is odd. If  is an odd integer, then

is an odd integer, then  is odd as well. Similarly, this same argument shows that when

is odd as well. Similarly, this same argument shows that when  is even,

is even,  will be even. Equation (15) shows that if

will be even. Equation (15) shows that if  is even,

is even,  is an integer multiple of

is an integer multiple of  . Therefore,

. Therefore,  is defined for

is defined for  even, and is thus the proper index to use when n is even, and similarly

even, and is thus the proper index to use when n is even, and similarly  is defined for

is defined for  odd, making it the proper index in this latter case.

odd, making it the proper index in this latter case.

Thus, from (6) and (23), for  even:

even:

and from (19) and (24), for  odd:

odd:

Lo and behold we are evaluating the same Cauchy index for both:

Sturm's theorem

Sturm gives us a method for evaluating  . His theorem states as follows:

. His theorem states as follows:

Given a sequence of polynomials  where:

where:

1) If  then

then  ,

,  , and

, and

2)  for

for

and we define  as the number of changes of sign in the sequence

as the number of changes of sign in the sequence  for a fixed value of

for a fixed value of  , then:

, then:

A sequence satisfying these requirements is obtained using the Euclidean algorithm, which is as follows:

Starting with  and

and  , and denoting the remainder of

, and denoting the remainder of  by

by  and similarly denoting the remainder of

and similarly denoting the remainder of  by

by  , and so on, we obtain the relationships:

, and so on, we obtain the relationships:

or in general

where the last non-zero remainder,  will therefore be the highest common factor of

will therefore be the highest common factor of  . It can be observed that the sequence so constructed will satisfy the conditions of Sturm's theorem, and thus an algorithm for determining the stated index has been developed.

. It can be observed that the sequence so constructed will satisfy the conditions of Sturm's theorem, and thus an algorithm for determining the stated index has been developed.

It is in applying Sturm's theorem (28) to (29), through the use of the Euclidean algorithm above that the Routh matrix is formed.

We get

and identifying the coefficients of this remainder by  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and so forth, makes our formed remainder

, and so forth, makes our formed remainder

where

Continuing with the Euclidean algorithm on these new coefficients gives us

where we again denote the coefficients of the remainder  by

by  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

making our formed remainder

,

making our formed remainder

and giving us

The rows of the Routh array are determined exactly by this algorithm when applied to the coefficients of (20). An observation worthy of note is that in the regular case the polynomials  and

and  have as the highest common factor

have as the highest common factor  and thus there will be

and thus there will be  polynomials in the chain

polynomials in the chain  .

.

Note now, that in determining the signs of the members of the sequence of polynomials  that at

that at  the dominating power of

the dominating power of  will be the first term of each of these polynomials, and thus only these coefficients corresponding to the highest powers of

will be the first term of each of these polynomials, and thus only these coefficients corresponding to the highest powers of  in

in  , and

, and  , which are

, which are  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , ... determine the signs of

, ... determine the signs of  ,

,  , ...,

, ...,  at

at  .

.

So we get  that is,

that is,  is the number of changes of sign in the sequence

is the number of changes of sign in the sequence  ,

,  ,

,  , ... which is the number of sign changes in the sequence

, ... which is the number of sign changes in the sequence  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , ... and

, ... and  ; that is

; that is  is the number of changes of sign in the sequence

is the number of changes of sign in the sequence  ,

,  ,

,  , ... which is the number of sign changes in the sequence

, ... which is the number of sign changes in the sequence  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , ...

, ...

Since our chain  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , ... will have

, ... will have  members it is clear that

members it is clear that  since within

since within  if going from

if going from  to

to  a sign change has not occurred, within

a sign change has not occurred, within

going from

going from  to

to  one has, and likewise for all

one has, and likewise for all  transitions (there will be no terms equal to zero) giving us

transitions (there will be no terms equal to zero) giving us  total sign changes.

total sign changes.

As  and

and  , and from (18)

, and from (18)  , we have that

, we have that  and have derived Routh's theorem -

and have derived Routh's theorem -

The number of roots of a real polynomial  which lie in the right half plane

which lie in the right half plane  is equal to the number of changes of sign in the first column of the Routh scheme.

is equal to the number of changes of sign in the first column of the Routh scheme.

And for the stable case where  then

then  by which we have Routh's famous criterion:

by which we have Routh's famous criterion:

In order for all the roots of the polynomial  to have negative real parts, it is necessary and sufficient that all of the elements in the first column of the Routh scheme be different from zero and of the same sign.

to have negative real parts, it is necessary and sufficient that all of the elements in the first column of the Routh scheme be different from zero and of the same sign.

References

- Hurwitz, A., "On the Conditions under which an Equation has only Roots with Negative Real Parts", Rpt. in Selected Papers on Mathematical Trends in Control Theory, Ed. R. T. Ballman et al. New York: Dover 1964

- Routh, E. J., A Treatise on the Stability of a Given State of Motion. London: Macmillan, 1877. Rpt. in Stability of Motion, Ed. A. T. Fuller. London: Taylor & Francis, 1975

- Felix Gantmacher (J.L. Brenner translator) (1959) Applications of the Theory of Matrices, pp 177–80, New York: Interscience.

Categories:

lie on the imaginary axis, and letting

lie on the imaginary axis, and letting

= The number of roots of

= The number of roots of  = The number of roots of

= The number of roots of

in polar form, we have

in polar form, we have

when the i root of

when the i root of  when the i root of

when the i root of

and

and

we need only evaluate this function

we need only evaluate this function  to determine

to determine  versus

versus

over an interval (a,b) where

over an interval (a,b) where  and

and  are integer multiples of

are integer multiples of  , this variation causing the function

, this variation causing the function  to have increased by

to have increased by  to

to  one more time than it has jumped from

one more time than it has jumped from  and

and  , implies that

, implies that  has jumped from

has jumped from  is

is  jumps from

jumps from  provided that at

provided that at  ,

,  is defined.

is defined.

versus

versus  , i = 0, 1, 2, ...) the ending point will be on an incongruity as well, by equation (17) (since

, i = 0, 1, 2, ...) the ending point will be on an incongruity as well, by equation (17) (since  , through adding

, through adding  over the interval (a,b) =

over the interval (a,b) =  when our starting (and thus ending) point is not an incongruity, and by evaluating

when our starting (and thus ending) point is not an incongruity, and by evaluating

to

to  is called the Cauchy Index of the tangent of the phase angle, the phase angle being

is called the Cauchy Index of the tangent of the phase angle, the phase angle being  , depending as

, depending as  is an integer multiple of

is an integer multiple of

is odd. If

is odd. If  is odd as well. Similarly, this same argument shows that when

is odd as well. Similarly, this same argument shows that when  is defined for

is defined for

. His theorem states as follows:

. His theorem states as follows:

where:

where:

then

then  ,

,  , and

, and

for

for

as the number of changes of sign in the sequence

as the number of changes of sign in the sequence

and

and  , and denoting the remainder of

, and denoting the remainder of  by

by  and similarly denoting the remainder of

and similarly denoting the remainder of  by

by  , and so on, we obtain the relationships:

, and so on, we obtain the relationships:

will therefore be the highest common factor of

will therefore be the highest common factor of  . It can be observed that the sequence so constructed will satisfy the conditions of Sturm's theorem, and thus an algorithm for determining the stated index has been developed.

. It can be observed that the sequence so constructed will satisfy the conditions of Sturm's theorem, and thus an algorithm for determining the stated index has been developed.

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and so forth, makes our formed remainder

, and so forth, makes our formed remainder

by

by  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

making our formed remainder

,

making our formed remainder

and

and  have as the highest common factor

have as the highest common factor  and thus there will be

and thus there will be  the dominating power of

the dominating power of  will be the first term of each of these polynomials, and thus only these coefficients corresponding to the highest powers of

will be the first term of each of these polynomials, and thus only these coefficients corresponding to the highest powers of  , and

, and  ,

,  ,

,  that is,

that is,  is the number of changes of sign in the sequence

is the number of changes of sign in the sequence  ,

,  ,

,  , ... which is the number of sign changes in the sequence

, ... which is the number of sign changes in the sequence  ; that is

; that is  is the number of changes of sign in the sequence

is the number of changes of sign in the sequence  ,

,  ,

,  , ... which is the number of sign changes in the sequence

, ... which is the number of sign changes in the sequence  ,

,  , ...

, ...

since within

since within  if going from

if going from  going from

going from  and

and  , and from (18)

, and from (18)  , we have that

, we have that  and have derived Routh's theorem -

and have derived Routh's theorem -

which lie in the right half plane

which lie in the right half plane  is equal to the number of changes of sign in the first column of the Routh scheme.

is equal to the number of changes of sign in the first column of the Routh scheme.

then

then  by which we have Routh's famous criterion:

by which we have Routh's famous criterion: