| Diamond | |

|---|---|

A natural diamond crystal A natural diamond crystal | |

| General | |

| Category | Native minerals |

| Formula (repeating unit) | C |

| IMA symbol | Dia |

| Strunz classification | 1.CB.10a |

| Dana classification | 1.3.6.1 |

| Crystal system | Cubic |

| Crystal class | Hexoctahedral (m3m) H-M symbol: (4/m 3 2/m) |

| Space group | Fd3m (No. 227) |

| Structure | |

| Jmol (3D) | Interactive image |

| Identification | |

| Formula mass | 12.01 g/mol |

| Color | Typically yellow, brown, or gray to colorless. Less often blue, green, black, translucent white, pink, violet, orange, purple, and red. |

| Crystal habit | Octahedral |

| Twinning | Spinel law common (yielding "macle") |

| Cleavage | 111 (perfect in four directions) |

| Fracture | Irregular/Uneven |

| Mohs scale hardness | 10 (defining mineral) |

| Luster | Adamantine |

| Streak | Colorless |

| Diaphaneity | Transparent to subtransparent to translucent |

| Specific gravity | 3.52±0.01 |

| Density | 3.5–3.53 g/cm 3500–3530 kg/m |

| Polish luster | Adamantine |

| Optical properties | Isotropic |

| Refractive index | 2.418 (at 500 nm) |

| Birefringence | None |

| Pleochroism | None |

| Dispersion | 0.044 |

| Melting point | Pressure dependent |

| References | |

Diamond is a solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Diamond as a form of carbon is tasteless, odourless, strong, brittle solid, colourless in pure form, a poor conductor of electricity, and insoluble in water. Another solid form of carbon known as graphite is the chemically stable form of carbon at room temperature and pressure, but diamond is metastable and converts to it at a negligible rate under those conditions. Diamond has the highest hardness and thermal conductivity of any natural material, properties that are used in major industrial applications such as cutting and polishing tools. They are also the reason that diamond anvil cells can subject materials to pressures found deep in the Earth.

Because the arrangement of atoms in diamond is extremely rigid, few types of impurity can contaminate it (two exceptions are boron and nitrogen). Small numbers of defects or impurities (about one per million of lattice atoms) can color a diamond blue (boron), yellow (nitrogen), brown (defects), green (radiation exposure), purple, pink, orange, or red. Diamond also has a very high refractive index and a relatively high optical dispersion.

Most natural diamonds have ages between 1 billion and 3.5 billion years. Most were formed at depths between 150 and 250 kilometres (93 and 155 mi) in the Earth's mantle, although a few have come from as deep as 800 kilometres (500 mi). Under high pressure and temperature, carbon-containing fluids dissolved various minerals and replaced them with diamonds. Much more recently (hundreds to tens of million years ago), they were carried to the surface in volcanic eruptions and deposited in igneous rocks known as kimberlites and lamproites.

Synthetic diamonds can be grown from high-purity carbon under high pressures and temperatures or from hydrocarbon gases by chemical vapor deposition (CVD). Natural and synthetic diamonds are most commonly distinguished using optical techniques or thermal conductivity measurements.

Properties

Main article: Material properties of diamondDiamond is a solid form of pure carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal. Solid carbon comes in different forms known as allotropes depending on the type of chemical bond. The two most common allotropes of pure carbon are diamond and graphite. In graphite, the bonds are sp orbital hybrids and the atoms form in planes, with each bound to three nearest neighbors, 120 degrees apart. In diamond, they are sp and the atoms form tetrahedra, with each bound to four nearest neighbors. Tetrahedra are rigid, the bonds are strong, and, of all known substances, diamond has the greatest number of atoms per unit volume, which is why it is both the hardest and the least compressible. It also has a high density, ranging from 3150 to 3530 kilograms per cubic metre (over three times the density of water) in natural diamonds and 3520 kg/m in pure diamond. In graphite, the bonds between nearest neighbors are even stronger, but the bonds between parallel adjacent planes are weak, so the planes easily slip past each other. Thus, graphite is much softer than diamond. However, the stronger bonds make graphite less flammable.

Diamonds have been adopted for many uses because of the material's exceptional physical characteristics. It has the highest thermal conductivity and the highest sound velocity. It has low adhesion and friction, and its coefficient of thermal expansion is extremely low. Its optical transparency extends from the far infrared to the deep ultraviolet and it has high optical dispersion. It also has high electrical resistance. It is chemically inert, not reacting with most corrosive substances, and has excellent biological compatibility.

Thermodynamics

The equilibrium pressure and temperature conditions for a transition between graphite and diamond are well established theoretically and experimentally. The equilibrium pressure varies linearly with temperature, between 1.7 GPa at 0 K and 12 GPa at 5000 K (the diamond/graphite/liquid triple point). However, the phases have a wide region about this line where they can coexist. At standard temperature and pressure, 20 °C (293 K) and 1 standard atmosphere (0.10 MPa), the stable phase of carbon is graphite, but diamond is metastable and its rate of conversion to graphite is negligible. However, at temperatures above about 4500 K, diamond rapidly converts to graphite. Rapid conversion of graphite to diamond requires pressures well above the equilibrium line: at 2000 K, a pressure of 35 GPa is needed.

Above the graphite–diamond–liquid carbon triple point, the melting point of diamond increases slowly with increasing pressure; but at pressures of hundreds of GPa, it decreases. At high pressures, silicon and germanium have a BC8 body-centered cubic crystal structure, and a similar structure is predicted for carbon at high pressures. At 0 K, the transition is predicted to occur at 1100 GPa.

Results published in an article in the scientific journal Nature Physics in 2010 suggest that, at ultra-high pressures and temperatures (about 10 million atmospheres or 1 TPa and 50,000 °C), diamond melts into a metallic fluid. The extreme conditions required for this to occur are present in the ice giants Neptune and Uranus. Both planets are made up of approximately 10 percent carbon and could hypothetically contain oceans of liquid carbon. Since large quantities of metallic fluid can affect the magnetic field, this could serve as an explanation as to why the geographic and magnetic poles of the two planets are unaligned.

Crystal structure

See also: Crystallographic defects in diamond

The most common crystal structure of diamond is called diamond cubic. It is formed of unit cells (see the figure) stacked together. Although there are 18 atoms in the figure, each corner atom is shared by eight unit cells and each atom in the center of a face is shared by two, so there are a total of eight atoms per unit cell. The length of each side of the unit cell is denoted by a and is 3.567 angstroms.

The nearest neighbor distance in the diamond lattice is 1.732a/4 where a is the lattice constant, usually given in Angstrøms as a = 3.567 Å, which is 0.3567 nm.

A diamond cubic lattice can be thought of as two interpenetrating face-centered cubic lattices with one displaced by 1⁄4 of the diagonal along a cubic cell, or as one lattice with two atoms associated with each lattice point. Viewed from a <1 1 1> crystallographic direction, it is formed of layers stacked in a repeating ABCABC ... pattern. Diamonds can also form an ABAB ... structure, which is known as hexagonal diamond or lonsdaleite, but this is far less common and is formed under different conditions from cubic carbon.

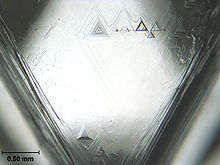

Crystal habit

Diamonds occur most often as euhedral or rounded octahedra and twinned octahedra known as macles. As diamond's crystal structure has a cubic arrangement of the atoms, they have many facets that belong to a cube, octahedron, rhombicosidodecahedron, tetrakis hexahedron, or disdyakis dodecahedron. The crystals can have rounded-off and unexpressive edges and can be elongated. Diamonds (especially those with rounded crystal faces) are commonly found coated in nyf, an opaque gum-like skin.

Some diamonds contain opaque fibers. They are referred to as opaque if the fibers grow from a clear substrate or fibrous if they occupy the entire crystal. Their colors range from yellow to green or gray, sometimes with cloud-like white to gray impurities. Their most common shape is cuboidal, but they can also form octahedra, dodecahedra, macles, or combined shapes. The structure is the result of numerous impurities with sizes between 1 and 5 microns. These diamonds probably formed in kimberlite magma and sampled the volatiles.

Diamonds can also form polycrystalline aggregates. There have been attempts to classify them into groups with names such as boart, ballas, stewartite, and framesite, but there is no widely accepted set of criteria. Carbonado, a type in which the diamond grains were sintered (fused without melting by the application of heat and pressure), is black in color and tougher than single crystal diamond. It has never been observed in a volcanic rock. There are many theories for its origin, including formation in a star, but no consensus.

Mechanical

Hardness

Diamond is the hardest material on the qualitative Mohs scale. To conduct the quantitative Vickers hardness test, samples of materials are struck with a pyramid of standardized dimensions using a known force – a diamond crystal is used for the pyramid to permit a wide range of materials to be tested. From the size of the resulting indentation, a Vickers hardness value for the material can be determined. Diamond's great hardness relative to other materials has been known since antiquity, and is the source of its name. This does not mean that it is infinitely hard, indestructible, or unscratchable. Indeed, diamonds can be scratched by other diamonds and worn down over time even by softer materials, such as vinyl phonograph records.

Diamond hardness depends on its purity, crystalline perfection, and orientation: hardness is higher for flawless, pure crystals oriented to the <111> direction (along the longest diagonal of the cubic diamond lattice). Therefore, whereas it might be possible to scratch some diamonds with other materials, such as boron nitride, the hardest diamonds can only be scratched by other diamonds and nanocrystalline diamond aggregates.

The hardness of diamond contributes to its suitability as a gemstone. Because it can only be scratched by other diamonds, it maintains its polish extremely well. Unlike many other gems, it is well-suited to daily wear because of its resistance to scratching—perhaps contributing to its popularity as the preferred gem in engagement or wedding rings, which are often worn every day.

The hardest natural diamonds mostly originate from the Copeton and Bingara fields located in the New England area in New South Wales, Australia. These diamonds are generally small, perfect to semiperfect octahedra, and are used to polish other diamonds. Their hardness is associated with the crystal growth form, which is single-stage crystal growth. Most other diamonds show more evidence of multiple growth stages, which produce inclusions, flaws, and defect planes in the crystal lattice, all of which affect their hardness. It is possible to treat regular diamonds under a combination of high pressure and high temperature to produce diamonds that are harder than the diamonds used in hardness gauges.

Diamonds cut glass, but this does not positively identify a diamond because other materials, such as quartz, also lie above glass on the Mohs scale and can also cut it. Diamonds can scratch other diamonds, but this can result in damage to one or both stones. Hardness tests are infrequently used in practical gemology because of their potentially destructive nature. The extreme hardness and high value of diamond means that gems are typically polished slowly, using painstaking traditional techniques and greater attention to detail than is the case with most other gemstones; these tend to result in extremely flat, highly polished facets with exceptionally sharp facet edges. Diamonds also possess an extremely high refractive index and fairly high dispersion. Taken together, these factors affect the overall appearance of a polished diamond and most diamantaires still rely upon skilled use of a loupe (magnifying glass) to identify diamonds "by eye".

Toughness

Somewhat related to hardness is another mechanical property toughness, which is a material's ability to resist breakage from forceful impact. The toughness of natural diamond has been measured as 50–65 MPa·m. This value is good compared to other ceramic materials, but poor compared to most engineering materials such as engineering alloys, which typically exhibit toughness over 80 MPa·m. As with any material, the macroscopic geometry of a diamond contributes to its resistance to breakage. Diamond has a cleavage plane and is therefore more fragile in some orientations than others. Diamond cutters use this attribute to cleave some stones before faceting them. "Impact toughness" is one of the main indexes to measure the quality of synthetic industrial diamonds.

Yield strength

Diamond has compressive yield strength of 130–140 GPa. This exceptionally high value, along with the hardness and transparency of diamond, are the reasons that diamond anvil cells are the main tool for high pressure experiments. These anvils have reached pressures of 600 GPa. Much higher pressures may be possible with nanocrystalline diamonds.

Elasticity and tensile strength

Usually, attempting to deform bulk diamond crystal by tension or bending results in brittle fracture. However, when single crystalline diamond is in the form of micro/nanoscale wires or needles (~100–300 nanometers in diameter, micrometers long), they can be elastically stretched by as much as 9–10 percent tensile strain without failure, with a maximum local tensile stress of about 89–98 GPa, very close to the theoretical limit for this material.

Electrical conductivity

Other specialized applications also exist or are being developed, including use as semiconductors: some blue diamonds are natural semiconductors, in contrast to most diamonds, which are excellent electrical insulators. The conductivity and blue color originate from boron impurity. Boron substitutes for carbon atoms in the diamond lattice, donating a hole into the valence band.

Substantial conductivity is commonly observed in nominally undoped diamond grown by chemical vapor deposition. This conductivity is associated with hydrogen-related species adsorbed at the surface, and it can be removed by annealing or other surface treatments.

Thin needles of diamond can be made to vary their electronic band gap from the normal 5.6 eV to near zero by selective mechanical deformation.

High-purity diamond wafers 5 cm in diameter exhibit perfect resistance in one direction and perfect conductance in the other, creating the possibility of using them for quantum data storage. The material contains only 3 parts per million of nitrogen. The diamond was grown on a stepped substrate, which eliminated cracking.

Surface property

Diamonds are naturally lipophilic and hydrophobic, which means the diamonds' surface cannot be wet by water, but can be easily wet and stuck by oil. This property can be utilized to extract diamonds using oil when making synthetic diamonds. However, when diamond surfaces are chemically modified with certain ions, they are expected to become so hydrophilic that they can stabilize multiple layers of water ice at human body temperature.

The surface of diamonds is partially oxidized. The oxidized surface can be reduced by heat treatment under hydrogen flow. That is to say, this heat treatment partially removes oxygen-containing functional groups. But diamonds (spC) are unstable against high temperature (above about 400 °C (752 °F)) under atmospheric pressure. The structure gradually changes into spC above this temperature. Thus, diamonds should be reduced below this temperature.

Chemical stability

At room temperature, diamonds do not react with any chemical reagents including strong acids and bases.

In an atmosphere of pure oxygen, diamond has an ignition point that ranges from 690 °C (1,274 °F) to 840 °C (1,540 °F); smaller crystals tend to burn more easily. It increases in temperature from red to white heat and burns with a pale blue flame, and continues to burn after the source of heat is removed. By contrast, in air the combustion will cease as soon as the heat is removed because the oxygen is diluted with nitrogen. A clear, flawless, transparent diamond is completely converted to carbon dioxide; any impurities will be left as ash. Heat generated from cutting a diamond will not ignite the diamond, and neither will a cigarette lighter, but house fires and blow torches are hot enough. Jewelers must be careful when molding the metal in a diamond ring.

Diamond powder of an appropriate grain size (around 50 microns) burns with a shower of sparks after ignition from a flame. Consequently, pyrotechnic compositions based on synthetic diamond powder can be prepared. The resulting sparks are of the usual red-orange color, comparable to charcoal, but show a very linear trajectory which is explained by their high density. Diamond also reacts with fluorine gas above about 700 °C (1,292 °F).

Color

Main article: Diamond color

Diamond has a wide band gap of 5.5 eV corresponding to the deep ultraviolet wavelength of 225 nanometers. This means that pure diamond should transmit visible light and appear as a clear colorless crystal. Colors in diamond originate from lattice defects and impurities. The diamond crystal lattice is exceptionally strong, and only atoms of nitrogen, boron, and hydrogen can be introduced into diamond during the growth at significant concentrations (up to atomic percents). Transition metals nickel and cobalt, which are commonly used for growth of synthetic diamond by high-pressure high-temperature techniques, have been detected in diamond as individual atoms; the maximum concentration is 0.01% for nickel and even less for cobalt. Virtually any element can be introduced to diamond by ion implantation.

Nitrogen is by far the most common impurity found in gem diamonds and is responsible for the yellow and brown color in diamonds. Boron is responsible for the blue color. Color in diamond has two additional sources: irradiation (usually by alpha particles), that causes the color in green diamonds, and plastic deformation of the diamond crystal lattice. Plastic deformation is the cause of color in some brown and perhaps pink and red diamonds. In order of increasing rarity, yellow diamond is followed by brown, colorless, then by blue, green, black, pink, orange, purple, and red. "Black", or carbonado, diamonds are not truly black, but rather contain numerous dark inclusions that give the gems their dark appearance. Colored diamonds contain impurities or structural defects that cause the coloration, while pure or nearly pure diamonds are transparent and colorless. Most diamond impurities replace a carbon atom in the crystal lattice, known as a carbon flaw. The most common impurity, nitrogen, causes a slight to intense yellow coloration depending upon the type and concentration of nitrogen present. The Gemological Institute of America (GIA) classifies low saturation yellow and brown diamonds as diamonds in the normal color range, and applies a grading scale from "D" (colorless) to "Z" (light yellow). Yellow diamonds of high color saturation or a different color, such as pink or blue, are called fancy colored diamonds and fall under a different grading scale.

In 2008, the Wittelsbach Diamond, a 35.56-carat (7.112 g) blue diamond once belonging to the King of Spain, fetched over US$24 million at a Christie's auction. In May 2009, a 7.03-carat (1.406 g) blue diamond fetched the highest price per carat ever paid for a diamond when it was sold at auction for 10.5 million Swiss francs (6.97 million euros, or US$9.5 million at the time). That record was, however, beaten the same year: a 5-carat (1.0 g) vivid pink diamond was sold for US$10.8 million in Hong Kong on December 1, 2009.

Clarity

Clarity is one of the 4C's (color, clarity, cut and carat weight) that helps in identifying the quality of diamonds. The Gemological Institute of America (GIA) developed 11 clarity scales to decide the quality of a diamond for its sale value. The GIA clarity scale spans from Flawless (FL) to included (I) having internally flawless (IF), very, very slightly included (VVS), very slightly included (VS) and slightly included (SI) in between. Impurities in natural diamonds are due to the presence of natural minerals and oxides. The clarity scale grades the diamond based on the color, size, location of impurity and quantity of clarity visible under 10x magnification. Inclusions in diamond can be extracted by optical methods. The process is to take pre-enhancement images, identifying the inclusion removal part and finally removing the diamond facets and noises.

Fluorescence

Between 25% and 35% of natural diamonds exhibit some degree of fluorescence when examined under invisible long-wave ultraviolet light or higher energy radiation sources such as X-rays and lasers. Incandescent lighting will not cause a diamond to fluoresce. Diamonds can fluoresce in a variety of colors including blue (most common), orange, yellow, white, green and very rarely red and purple. Although the causes are not well understood, variations in the atomic structure, such as the number of nitrogen atoms present are thought to contribute to the phenomenon.

Thermal conductivity

Diamonds can be identified by their high thermal conductivity (900–2320 W·m·K). Their high refractive index is also indicative, but other materials have similar refractivity.

Geology

Diamonds are extremely rare, with concentrations of at most parts per billion in source rock. Before the 20th century, most diamonds were found in alluvial deposits. Loose diamonds are also found along existing and ancient shorelines, where they tend to accumulate because of their size and density. Rarely, they have been found in glacial till (notably in Wisconsin and Indiana), but these deposits are not of commercial quality. These types of deposit were derived from localized igneous intrusions through weathering and transport by wind or water.

Most diamonds come from the Earth's mantle, and most of this section discusses those diamonds. However, there are other sources. Some blocks of the crust, or terranes, have been buried deep enough as the crust thickened so they experienced ultra-high-pressure metamorphism. These have evenly distributed microdiamonds that show no sign of transport by magma. In addition, when meteorites strike the ground, the shock wave can produce high enough temperatures and pressures for microdiamonds and nanodiamonds to form. Impact-type microdiamonds can be used as an indicator of ancient impact craters. Popigai impact structure in Russia may have the world's largest diamond deposit, estimated at trillions of carats, and formed by an asteroid impact.

A common misconception is that diamonds form from highly compressed coal. Coal is formed from buried prehistoric plants, and most diamonds that have been dated are far older than the first land plants. It is possible that diamonds can form from coal in subduction zones, but diamonds formed in this way are rare, and the carbon source is more likely carbonate rocks and organic carbon in sediments, rather than coal.

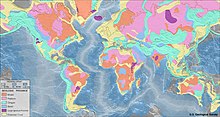

Surface distribution

Diamonds are far from evenly distributed over the Earth. A rule of thumb known as Clifford's rule states that they are almost always found in kimberlites on the oldest part of cratons, the stable cores of continents with typical ages of 2.5 billion years or more. However, there are exceptions. The Argyle diamond mine in Australia, the largest producer of diamonds by weight in the world, is located in a mobile belt, also known as an orogenic belt, a weaker zone surrounding the central craton that has undergone compressional tectonics. Instead of kimberlite, the host rock is lamproite. Lamproites with diamonds that are not economically viable are also found in the United States, India, and Australia. In addition, diamonds in the Wawa belt of the Superior province in Canada and microdiamonds in the island arc of Japan are found in a type of rock called lamprophyre.

Kimberlites can be found in narrow (1 to 4 meters) dikes and sills, and in pipes with diameters that range from about 75 m to 1.5 km. Fresh rock is dark bluish green to greenish gray, but after exposure rapidly turns brown and crumbles. It is hybrid rock with a chaotic mixture of small minerals and rock fragments (clasts) up to the size of watermelons. They are a mixture of xenocrysts and xenoliths (minerals and rocks carried up from the lower crust and mantle), pieces of surface rock, altered minerals such as serpentine, and new minerals that crystallized during the eruption. The texture varies with depth. The composition forms a continuum with carbonatites, but the latter have too much oxygen for carbon to exist in a pure form. Instead, it is locked up in the mineral calcite (CaCO

3).

All three of the diamond-bearing rocks (kimberlite, lamproite and lamprophyre) lack certain minerals (melilite and kalsilite) that are incompatible with diamond formation. In kimberlite, olivine is large and conspicuous, while lamproite has Ti-phlogopite and lamprophyre has biotite and amphibole. They are all derived from magma types that erupt rapidly from small amounts of melt, are rich in volatiles and magnesium oxide, and are less oxidizing than more common mantle melts such as basalt. These characteristics allow the melts to carry diamonds to the surface before they dissolve.

Exploration

Kimberlite pipes can be difficult to find. They weather quickly (within a few years after exposure) and tend to have lower topographic relief than surrounding rock. If they are visible in outcrops, the diamonds are never visible because they are so rare. In any case, kimberlites are often covered with vegetation, sediments, soils, or lakes. In modern searches, geophysical methods such as aeromagnetic surveys, electrical resistivity, and gravimetry, help identify promising regions to explore. This is aided by isotopic dating and modeling of the geological history. Then surveyors must go to the area and collect samples, looking for kimberlite fragments or indicator minerals. The latter have compositions that reflect the conditions where diamonds form, such as extreme melt depletion or high pressures in eclogites. However, indicator minerals can be misleading; a better approach is geothermobarometry, where the compositions of minerals are analyzed as if they were in equilibrium with mantle minerals.

Finding kimberlites requires persistence, and only a small fraction contain diamonds that are commercially viable. The only major discoveries since about 1980 have been in Canada. Since existing mines have lifetimes of as little as 25 years, there could be a shortage of new natural diamonds in the future.

Ages

Diamonds are dated by analyzing inclusions using the decay of radioactive isotopes. Depending on the elemental abundances, one can look at the decay of rubidium to strontium, samarium to neodymium, uranium to lead, argon-40 to argon-39, or rhenium to osmium. Those found in kimberlites have ages ranging from 1 to 3.5 billion years, and there can be multiple ages in the same kimberlite, indicating multiple episodes of diamond formation. The kimberlites themselves are much younger. Most of them have ages between tens of millions and 300 million years old, although there are some older exceptions (Argyle, Premier and Wawa). Thus, the kimberlites formed independently of the diamonds and served only to transport them to the surface. Kimberlites are also much younger than the cratons they have erupted through. The reason for the lack of older kimberlites is unknown, but it suggests there was some change in mantle chemistry or tectonics. No kimberlite has erupted in human history.

Origin in mantle

Most gem-quality diamonds come from depths of 150–250 km in the lithosphere. Such depths occur below cratons in mantle keels, the thickest part of the lithosphere. These regions have high enough pressure and temperature to allow diamonds to form and they are not convecting, so diamonds can be stored for billions of years until a kimberlite eruption samples them.

Host rocks in a mantle keel include harzburgite and lherzolite, two type of peridotite. The most dominant rock type in the upper mantle, peridotite is an igneous rock consisting mostly of the minerals olivine and pyroxene; it is low in silica and high in magnesium. However, diamonds in peridotite rarely survive the trip to the surface. Another common source that does keep diamonds intact is eclogite, a metamorphic rock that typically forms from basalt as an oceanic plate plunges into the mantle at a subduction zone.

A smaller fraction of diamonds (about 150 have been studied) come from depths of 330–660 km, a region that includes the transition zone. They formed in eclogite but are distinguished from diamonds of shallower origin by inclusions of majorite (a form of garnet with excess silicon). A similar proportion of diamonds comes from the lower mantle at depths between 660 and 800 km.

Diamond is thermodynamically stable at high pressures and temperatures, with the phase transition from graphite occurring at greater temperatures as the pressure increases. Thus, underneath continents it becomes stable at temperatures of 950 degrees Celsius and pressures of 4.5 gigapascals, corresponding to depths of 150 kilometers or greater. In subduction zones, which are colder, it becomes stable at temperatures of 800 °C and pressures of 3.5 gigapascals. At depths greater than 240 km, iron–nickel metal phases are present and carbon is likely to be either dissolved in them or in the form of carbides. Thus, the deeper origin of some diamonds may reflect unusual growth environments.

In 2018 the first known natural samples of a phase of ice called Ice VII were found as inclusions in diamond samples. The inclusions formed at depths between 400 and 800 km, straddling the upper and lower mantle, and provide evidence for water-rich fluid at these depths.

Carbon sources

The mantle has roughly one billion gigatonnes of carbon (for comparison, the atmosphere-ocean system has about 44,000 gigatonnes). Carbon has two stable isotopes, C and C, in a ratio of approximately 99:1 by mass. This ratio has a wide range in meteorites, which implies that it also varied a lot in the early Earth. It can also be altered by surface processes like photosynthesis. The fraction is generally compared to a standard sample using a ratio δC expressed in parts per thousand. Common rocks from the mantle such as basalts, carbonatites, and kimberlites have ratios between −8 and −2. On the surface, organic sediments have an average of −25 while carbonates have an average of 0.

Populations of diamonds from different sources have distributions of δC that vary markedly. Peridotitic diamonds are mostly within the typical mantle range; eclogitic diamonds have values from −40 to +3, although the peak of the distribution is in the mantle range. This variability implies that they are not formed from carbon that is primordial (having resided in the mantle since the Earth formed). Instead, they are the result of tectonic processes, although (given the ages of diamonds) not necessarily the same tectonic processes that act in the present.

Formation and growth

Diamonds in the mantle form through a metasomatic process where a C–O–H–N–S fluid or melt dissolves minerals in a rock and replaces them with new minerals. (The vague term C–O–H–N–S is commonly used because the exact composition is not known.) Diamonds form from this fluid either by reduction of oxidized carbon (e.g., CO2 or CO3) or oxidation of a reduced phase such as methane.

Using probes such as polarized light, photoluminescence, and cathodoluminescence, a series of growth zones can be identified in diamonds. The characteristic pattern in diamonds from the lithosphere involves a nearly concentric series of zones with very thin oscillations in luminescence and alternating episodes where the carbon is resorbed by the fluid and then grown again. Diamonds from below the lithosphere have a more irregular, almost polycrystalline texture, reflecting the higher temperatures and pressures as well as the transport of the diamonds by convection.

Transport to the surface

Geological evidence supports a model in which kimberlite magma rises at 4–20 meters per second, creating an upward path by hydraulic fracturing of the rock. As the pressure decreases, a vapor phase exsolves from the magma, and this helps to keep the magma fluid. At the surface, the initial eruption explodes out through fissures at high speeds (over 200 m/s (450 mph)). Then, at lower pressures, the rock is eroded, forming a pipe and producing fragmented rock (breccia). As the eruption wanes, there is pyroclastic phase and then metamorphism and hydration produces serpentinites.

Double diamonds

In rare cases, diamonds have been found that contain a cavity within which is a second diamond. The first double diamond, the Matryoshka, was found by Alrosa in Yakutia, Russia, in 2019. Another one was found in the Ellendale Diamond Field in Western Australia in 2021.

In space

Main article: Extraterrestrial diamondsAlthough diamonds on Earth are rare, they are very common in space. In meteorites, about three percent of the carbon is in the form of nanodiamonds, having diameters of a few nanometers. Sufficiently small diamonds can form in the cold of space because their lower surface energy makes them more stable than graphite. The isotopic signatures of some nanodiamonds indicate they were formed outside the Solar System in stars.

High pressure experiments predict that large quantities of diamonds condense from methane into a "diamond rain" on the ice giant planets Uranus and Neptune. Some extrasolar planets may be almost entirely composed of diamond.

Diamonds may exist in carbon-rich stars, particularly white dwarfs. One theory for the origin of carbonado, the toughest form of diamond, is that it originated in a white dwarf or supernova. Diamonds formed in stars may have been the first minerals.

Industry

See also: Diamonds as an investment, List of countries by diamond production, and Clean Diamond Trade Act

The most familiar uses of diamonds today are as gemstones used for adornment, and as industrial abrasives for cutting hard materials. The markets for gem-grade and industrial-grade diamonds value diamonds differently.

Gem-grade diamonds

Main article: Diamond (gemstone)The dispersion of white light into spectral colors is the primary gemological characteristic of gem diamonds. In the 20th century, experts in gemology developed methods of grading diamonds and other gemstones based on the characteristics most important to their value as a gem. Four characteristics, known informally as the four Cs, are now commonly used as the basic descriptors of diamonds: these are its mass in carats (a carat being equal to 0.2 grams), cut (quality of the cut is graded according to proportions, symmetry and polish), color (how close to white or colorless; for fancy diamonds how intense is its hue), and clarity (how free is it from inclusions). A large, flawless diamond is known as a paragon.

A large trade in gem-grade diamonds exists. Although most gem-grade diamonds are sold newly polished, there is a well-established market for resale of polished diamonds (e.g. pawnbroking, auctions, second-hand jewelry stores, diamantaires, bourses, etc.). One hallmark of the trade in gem-quality diamonds is its remarkable concentration: wholesale trade and diamond cutting is limited to just a few locations; in 2003, 92% of the world's diamonds were cut and polished in Surat, India. Other important centers of diamond cutting and trading are the Antwerp diamond district in Belgium, where the International Gemological Institute is based, London, the Diamond District in New York City, the Diamond Exchange District in Tel Aviv and Amsterdam. One contributory factor is the geological nature of diamond deposits: several large primary kimberlite-pipe mines each account for significant portions of market share (such as the Jwaneng mine in Botswana, which is a single large-pit mine that can produce between 12,500,000 and 15,000,000 carats (2,500 and 3,000 kg) of diamonds per year). Secondary alluvial diamond deposits, on the other hand, tend to be fragmented amongst many different operators because they can be dispersed over many hundreds of square kilometers (e.g., alluvial deposits in Brazil).

The production and distribution of diamonds is largely consolidated in the hands of a few key players, and concentrated in traditional diamond trading centers, the most important being Antwerp, where 80% of all rough diamonds, 50% of all cut diamonds and more than 50% of all rough, cut and industrial diamonds combined are handled. This makes Antwerp a de facto "world diamond capital". The city of Antwerp also hosts the Antwerpsche Diamantkring, created in 1929 to become the first and biggest diamond bourse dedicated to rough diamonds. Another important diamond center is New York City, where almost 80% of the world's diamonds are sold, including auction sales.

The De Beers company, as the world's largest diamond mining company, holds a dominant position in the industry, and has done so since soon after its founding in 1888 by the British businessman Cecil Rhodes. De Beers is currently the world's largest operator of diamond production facilities (mines) and distribution channels for gem-quality diamonds. The Diamond Trading Company (DTC) is a subsidiary of De Beers and markets rough diamonds from De Beers-operated mines. De Beers and its subsidiaries own mines that produce some 40% of annual world diamond production. For most of the 20th century over 80% of the world's rough diamonds passed through De Beers, but by 2001–2009 the figure had decreased to around 45%, and by 2013 the company's market share had further decreased to around 38% in value terms and even less by volume. De Beers sold off the vast majority of its diamond stockpile in the late 1990s – early 2000s and the remainder largely represents working stock (diamonds that are being sorted before sale). This was well documented in the press but remains little known to the general public.

As a part of reducing its influence, De Beers withdrew from purchasing diamonds on the open market in 1999 and ceased, at the end of 2008, purchasing Russian diamonds mined by the largest Russian diamond company Alrosa. As of January 2011, De Beers states that it only sells diamonds from the following four countries: Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and Canada. Alrosa had to suspend their sales in October 2008 due to the global energy crisis, but the company reported that it had resumed selling rough diamonds on the open market by October 2009. Apart from Alrosa, other important diamond mining companies include BHP, which is the world's largest mining company; Rio Tinto, the owner of the Argyle (100%), Diavik (60%), and Murowa (78%) diamond mines; and Petra Diamonds, the owner of several major diamond mines in Africa.

Further down the supply chain, members of The World Federation of Diamond Bourses (WFDB) act as a medium for wholesale diamond exchange, trading both polished and rough diamonds. The WFDB consists of independent diamond bourses in major cutting centers such as Tel Aviv, Antwerp, Johannesburg and other cities across the US, Europe and Asia. In 2000, the WFDB and The International Diamond Manufacturers Association established the World Diamond Council to prevent the trading of diamonds used to fund war and inhumane acts. WFDB's additional activities include sponsoring the World Diamond Congress every two years, as well as the establishment of the International Diamond Council (IDC) to oversee diamond grading.

Once purchased by Sightholders (which is a trademark term referring to the companies that have a three-year supply contract with DTC), diamonds are cut and polished in preparation for sale as gemstones ('industrial' stones are regarded as a by-product of the gemstone market; they are used for abrasives). The cutting and polishing of rough diamonds is a specialized skill that is concentrated in a limited number of locations worldwide. Traditional diamond cutting centers are Antwerp, Amsterdam, Johannesburg, New York City, and Tel Aviv. Recently, diamond cutting centers have been established in China, India, Thailand, Namibia and Botswana. Cutting centers with lower cost of labor, notably Surat in Gujarat, India, handle a larger number of smaller carat diamonds, while smaller quantities of larger or more valuable diamonds are more likely to be handled in Europe or North America. The recent expansion of this industry in India, employing low cost labor, has allowed smaller diamonds to be prepared as gems in greater quantities than was previously economically feasible.

Diamonds prepared as gemstones are sold on diamond exchanges called bourses. There are 28 registered diamond bourses in the world. Bourses are the final tightly controlled step in the diamond supply chain; wholesalers and even retailers are able to buy relatively small lots of diamonds at the bourses, after which they are prepared for final sale to the consumer. Diamonds can be sold already set in jewelry, or sold unset ("loose"). According to the Rio Tinto, in 2002 the diamonds produced and released to the market were valued at US$9 billion as rough diamonds, US$14 billion after being cut and polished, US$28 billion in wholesale diamond jewelry, and US$57 billion in retail sales.

Cutting

Main articles: Diamond cutting and Diamond cut

Mined rough diamonds are converted into gems through a multi-step process called "cutting". Diamonds are extremely hard, but also brittle and can be split up by a single blow. Therefore, diamond cutting is traditionally considered as a delicate procedure requiring skills, scientific knowledge, tools and experience. Its final goal is to produce a faceted jewel where the specific angles between the facets would optimize the diamond luster, that is dispersion of white light, whereas the number and area of facets would determine the weight of the final product. The weight reduction upon cutting is significant and can be of the order of 50%. Several possible shapes are considered, but the final decision is often determined not only by scientific, but also practical considerations. For example, the diamond might be intended for display or for wear, in a ring or a necklace, singled or surrounded by other gems of certain color and shape. Some of them may be considered as classical, such as round, pear, marquise, oval, hearts and arrows diamonds, etc. Some of them are special, produced by certain companies, for example, Phoenix, Cushion, Sole Mio diamonds, etc.

The most time-consuming part of the cutting is the preliminary analysis of the rough stone. It needs to address a large number of issues, bears much responsibility, and therefore can last years in case of unique diamonds. The following issues are considered:

- The hardness of diamond and its ability to cleave strongly depend on the crystal orientation. Therefore, the crystallographic structure of the diamond to be cut is analyzed using X-ray diffraction to choose the optimal cutting directions.

- Most diamonds contain visible non-diamond inclusions and crystal flaws. The cutter has to decide which flaws are to be removed by the cutting and which could be kept.

- Splitting a diamond with a hammer is difficult, a well-calculated, angled blow can cut the diamond, piece-by-piece, but it can also ruin the diamond itself. Alternatively, it can be cut with a diamond saw, which is a more reliable method.

After initial cutting, the diamond is shaped in numerous stages of polishing. Unlike cutting, which is a responsible but quick operation, polishing removes material by gradual erosion and is extremely time-consuming. The associated technique is well developed; it is considered as a routine and can be performed by technicians. After polishing, the diamond is reexamined for possible flaws, either remaining or induced by the process. Those flaws are concealed through various diamond enhancement techniques, such as repolishing, crack filling, or clever arrangement of the stone in the jewelry. Remaining non-diamond inclusions are removed through laser drilling and filling of the voids produced.

Marketing

Marketing has significantly affected the image of diamond as a valuable commodity.

N. W. Ayer & Son, the advertising firm retained by De Beers in the mid-20th century, succeeded in reviving the American diamond market and the firm created new markets in countries where no diamond tradition had existed before. N. W. Ayer's marketing included product placement, advertising focused on the diamond product itself rather than the De Beers brand, and associations with celebrities and royalty. Without advertising the De Beers brand, De Beers was advertising its competitors' diamond products as well, but this was not a concern as De Beers dominated the diamond market throughout the 20th century. De Beers' market share dipped temporarily to second place in the global market below Alrosa in the aftermath of the global economic crisis of 2008, down to less than 29% in terms of carats mined, rather than sold. The campaign lasted for decades but was effectively discontinued by early 2011. De Beers still advertises diamonds, but the advertising now mostly promotes its own brands, or licensed product lines, rather than completely "generic" diamond products. The campaign was perhaps best captured by the slogan "a diamond is forever". This slogan is now being used by De Beers Diamond Jewelers, a jewelry firm which is a 50/50% joint venture between the De Beers mining company and LVMH, the luxury goods conglomerate.

Brown-colored diamonds constituted a significant part of the diamond production, and were predominantly used for industrial purposes. They were seen as worthless for jewelry (not even being assessed on the diamond color scale). After the development of Argyle diamond mine in Australia in 1986, and marketing, brown diamonds have become acceptable gems. The change was mostly due to the numbers: the Argyle mine, with its 35,000,000 carats (7,000 kg) of diamonds per year, makes about one-third of global production of natural diamonds; 80% of Argyle diamonds are brown.

Industrial-grade diamonds

Industrial diamonds are valued mostly for their hardness and thermal conductivity, making many of the gemological characteristics of diamonds, such as the 4 Cs, irrelevant for most applications. Eighty percent of mined diamonds (equal to about 135,000,000 carats (27,000 kg) annually) are unsuitable for use as gemstones and are used industrially. In addition to mined diamonds, synthetic diamonds found industrial applications almost immediately after their invention in the 1950s; in 2014, 4,500,000,000 carats (900,000 kg) of synthetic diamonds were produced, 90% of which were produced in China. Approximately 90% of diamond grinding grit is currently of synthetic origin.

The boundary between gem-quality diamonds and industrial diamonds is poorly defined and partly depends on market conditions (for example, if demand for polished diamonds is high, some lower-grade stones will be polished into low-quality or small gemstones rather than being sold for industrial use). Within the category of industrial diamonds, there is a sub-category comprising the lowest-quality, mostly opaque stones, which are known as bort.

Industrial use of diamonds has historically been associated with their hardness, which makes diamond the ideal material for cutting and grinding tools. As the hardest known naturally occurring material, diamond can be used to polish, cut, or wear away any material, including other diamonds. Common industrial applications of this property include diamond-tipped drill bits and saws, and the use of diamond powder as an abrasive. Less expensive industrial-grade diamonds (bort) with more flaws and poorer color than gems, are used for such purposes. Diamond is not suitable for machining ferrous alloys at high speeds, as carbon is soluble in iron at the high temperatures created by high-speed machining, leading to greatly increased wear on diamond tools compared to alternatives.

Specialized applications include use in laboratories as containment for high-pressure experiments (see diamond anvil cell), high-performance bearings, and limited use in specialized windows. With the continuing advances being made in the production of synthetic diamonds, future applications are becoming feasible. The high thermal conductivity of diamond makes it suitable as a heat sink for integrated circuits in electronics.

Mining

See also: List of diamond mines and Exploration diamond drillingApproximately 130,000,000 carats (26,000 kg) of diamonds are mined annually, with a total value of nearly US$9 billion, and about 100,000 kg (220,000 lb) are synthesized annually.

Roughly 49% of diamonds originate from Central and Southern Africa, although significant sources of the mineral have been discovered in Canada, India, Russia, Brazil, and Australia. They are mined from kimberlite and lamproite volcanic pipes, which can bring diamond crystals, originating from deep within the Earth where high pressures and temperatures enable them to form, to the surface. The mining and distribution of natural diamonds are subjects of frequent controversy such as concerns over the sale of blood diamonds or conflict diamonds by African paramilitary groups. The diamond supply chain is controlled by a limited number of powerful businesses, and is also highly concentrated in a small number of locations around the world.

Only a very small fraction of the diamond ore consists of actual diamonds. The ore is crushed, during which care is required not to destroy larger diamonds, and then sorted by density. Today, diamonds are located in the diamond-rich density fraction with the help of X-ray fluorescence, after which the final sorting steps are done by hand. Before the use of X-rays became commonplace, the separation was done with grease belts; diamonds have a stronger tendency to stick to grease than the other minerals in the ore.

Historically, diamonds were found only in alluvial deposits in Guntur and Krishna district of the Krishna River delta in Southern India. India led the world in diamond production from the time of their discovery in approximately the 9th century BC to the mid-18th century AD, but the commercial potential of these sources had been exhausted by the late 18th century and at that time India was eclipsed by Brazil where the first non-Indian diamonds were found in 1725. Currently, one of the most prominent Indian mines is located at Panna.

Diamond extraction from primary deposits (kimberlites and lamproites) started in the 1870s after the discovery of the Diamond Fields in South Africa. Production has increased over time and now an accumulated total of 4,500,000,000 carats (900,000 kg) have been mined since that date. Twenty percent of that amount has been mined in the last five years, and during the last 10 years, nine new mines have started production; four more are waiting to be opened soon. Most of these mines are located in Canada, Zimbabwe, Angola, and one in Russia.

In the U.S., diamonds have been found in Arkansas, Colorado, New Mexico, Wyoming, and Montana. In 2004, the discovery of a microscopic diamond in the U.S. led to the January 2008 bulk-sampling of kimberlite pipes in a remote part of Montana. The Crater of Diamonds State Park in Arkansas is open to the public, and is the only mine in the world where members of the public can dig for diamonds.

Today, most commercially viable diamond deposits are in Russia (mostly in Sakha Republic, for example Mir pipe and Udachnaya pipe), Botswana, Australia (Northern and Western Australia) and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In 2005, Russia produced almost one-fifth of the global diamond output, according to the British Geological Survey. Australia boasts the richest diamantiferous pipe, with production from the Argyle diamond mine reaching peak levels of 42 metric tons per year in the 1990s. There are also commercial deposits being actively mined in the Northwest Territories of Canada and Brazil. Diamond prospectors continue to search the globe for diamond-bearing kimberlite and lamproite pipes.

Political issues

Main articles: Kimberley Process, Blood diamond, and Child labour in the diamond industryIn some of the more politically unstable central African and west African countries, revolutionary groups have taken control of diamond mines, using proceeds from diamond sales to finance their operations. Diamonds sold through this process are known as conflict diamonds or blood diamonds.

In response to public concerns that their diamond purchases were contributing to war and human rights abuses in central and western Africa, the United Nations, the diamond industry and diamond-trading nations introduced the Kimberley Process in 2002. The Kimberley Process aims to ensure that conflict diamonds do not become intermixed with the diamonds not controlled by such rebel groups. This is done by requiring diamond-producing countries to provide proof that the money they make from selling the diamonds is not used to fund criminal or revolutionary activities. Although the Kimberley Process has been moderately successful in limiting the number of conflict diamonds entering the market, some still find their way in. According to the International Diamond Manufacturers Association, conflict diamonds constitute 2–3% of all diamonds traded. Two major flaws still hinder the effectiveness of the Kimberley Process: (1) the relative ease of smuggling diamonds across African borders, and (2) the violent nature of diamond mining in nations that are not in a technical state of war and whose diamonds are therefore considered "clean".

The Canadian Government has set up a body known as the Canadian Diamond Code of Conduct to help authenticate Canadian diamonds. This is a stringent tracking system of diamonds and helps protect the "conflict free" label of Canadian diamonds.

Mineral resource exploitation in general causes irreversible environmental damage, which must be weighed against the socio-economic benefits to a country.

Synthetics, simulants, and enhancements

Synthetics

Main article: Synthetic diamondSynthetic diamonds are diamonds manufactured in a laboratory, as opposed to diamonds mined from the Earth. The gemological and industrial uses of diamond have created a large demand for rough stones. This demand has been satisfied in large part by synthetic diamonds, which have been manufactured by various processes for more than half a century. However, in recent years it has become possible to produce gem-quality synthetic diamonds of significant size. It is possible to make colorless synthetic gemstones that, on a molecular level, are identical to natural stones and so visually similar that only a gemologist with special equipment can tell the difference.

The majority of commercially available synthetic diamonds are yellow and are produced by so-called high-pressure high-temperature (HPHT) processes. The yellow color is caused by nitrogen impurities. Other colors may also be reproduced such as blue, green or pink, which are a result of the addition of boron or from irradiation after synthesis.

Another popular method of growing synthetic diamond is chemical vapor deposition (CVD). The growth occurs under low pressure (below atmospheric pressure). It involves feeding a mixture of gases (typically 1 to 99 methane to hydrogen) into a chamber and splitting them into chemically active radicals in a plasma ignited by microwaves, hot filament, arc discharge, welding torch, or laser. This method is mostly used for coatings, but can also produce single crystals several millimeters in size (see picture).

As of 2010, nearly all 5,000 million carats (1,000 tonnes) of synthetic diamonds produced per year are for industrial use. Around 50% of the 133 million carats of natural diamonds mined per year end up in industrial use. Mining companies' expenses average 40 to 60 US dollars per carat for natural colorless diamonds, while synthetic manufacturers' expenses average $2,500 per carat for synthetic, gem-quality colorless diamonds. However, a purchaser is more likely to encounter a synthetic when looking for a fancy-colored diamond because only 0.01% of natural diamonds are fancy-colored, while most synthetic diamonds are colored in some way.

-

Synthetic diamonds of various colors grown by the high-pressure high-temperature technique

-

Colorless gem cut from diamond grown by chemical vapor deposition

Colorless gem cut from diamond grown by chemical vapor deposition

Simulants

Main article: Diamond simulant

A diamond simulant is a non-diamond material that is used to simulate the appearance of a diamond, and may be referred to as diamante. Cubic zirconia is the most common. The gemstone moissanite (silicon carbide) can be treated as a diamond simulant, though more costly to produce than cubic zirconia. Both are produced synthetically.

Enhancements

Main article: Diamond enhancementDiamond enhancements are specific treatments performed on natural or synthetic diamonds (usually those already cut and polished into a gem), which are designed to better the gemological characteristics of the stone in one or more ways. These include laser drilling to remove inclusions, application of sealants to fill cracks, treatments to improve a white diamond's color grade, and treatments to give fancy color to a white diamond.

Coatings are increasingly used to give a diamond simulant such as cubic zirconia a more "diamond-like" appearance. One such substance is diamond-like carbon—an amorphous carbonaceous material that has some physical properties similar to those of the diamond. Advertising suggests that such a coating would transfer some of these diamond-like properties to the coated stone, hence enhancing the diamond simulant. Techniques such as Raman spectroscopy should easily identify such a treatment.

Identification

Early diamond identification tests included a scratch test relying on the superior hardness of diamond. This test is destructive, as a diamond can scratch another diamond, and is rarely used nowadays. Instead, diamond identification relies on its superior thermal conductivity. Electronic thermal probes are widely used in the gemological centers to separate diamonds from their imitations. These probes consist of a pair of battery-powered thermistors mounted in a fine copper tip. One thermistor functions as a heating device while the other measures the temperature of the copper tip: if the stone being tested is a diamond, it will conduct the tip's thermal energy rapidly enough to produce a measurable temperature drop. This test takes about two to three seconds.

Whereas the thermal probe can separate diamonds from most of their simulants, distinguishing between various types of diamond, for example synthetic or natural, irradiated or non-irradiated, etc., requires more advanced, optical techniques. Those techniques are also used for some diamonds simulants, such as silicon carbide, which pass the thermal conductivity test. Optical techniques can distinguish between natural diamonds and synthetic diamonds. They can also identify the vast majority of treated natural diamonds. "Perfect" crystals (at the atomic lattice level) have never been found, so both natural and synthetic diamonds always possess characteristic imperfections, arising from the circumstances of their crystal growth, that allow them to be distinguished from each other.

Laboratories use techniques such as spectroscopy, microscopy, and luminescence under shortwave ultraviolet light to determine a diamond's origin. They also use specially made instruments to aid them in the identification process. Two screening instruments are the DiamondSure and the DiamondView, both produced by the DTC and marketed by the GIA.

Several methods for identifying synthetic diamonds can be performed, depending on the method of production and the color of the diamond. CVD diamonds can usually be identified by an orange fluorescence. D–J colored diamonds can be screened through the Swiss Gemmological Institute's Diamond Spotter. Stones in the D–Z color range can be examined through the DiamondSure UV/visible spectrometer, a tool developed by De Beers. Similarly, natural diamonds usually have minor imperfections and flaws, such as inclusions of foreign material, that are not seen in synthetic diamonds.

Screening devices based on diamond type detection can be used to make a distinction between diamonds that are certainly natural and diamonds that are potentially synthetic. Those potentially synthetic diamonds require more investigation in a specialized lab. Examples of commercial screening devices are D-Screen (WTOCD / HRD Antwerp), Alpha Diamond Analyzer (Bruker / HRD Antwerp), and D-Secure (DRC Techno).

Etymology, earliest use and composition discovery

The name diamond is derived from Ancient Greek: ἀδάμας (adámas), 'proper, unalterable, unbreakable, untamed', from ἀ- (a-), 'not' + Ancient Greek: δαμάω (damáō), 'to overpower, tame'. Diamonds are thought to have been first recognized and mined in India, where significant alluvial deposits of the stone could be found many centuries ago along the rivers Penner, Krishna, and Godavari. Diamonds have been known in India for at least 3,000 years but most likely 6,000 years.

Diamonds have been treasured as gemstones since their use as religious icons in ancient India. Their usage in engraving tools also dates to early human history. The popularity of diamonds has risen since the 19th century because of increased supply, improved cutting and polishing techniques, growth in the world economy, and innovative and successful advertising campaigns.

In 1772, the French scientist Antoine Lavoisier used a lens to concentrate the rays of the sun on a diamond in an atmosphere of oxygen, and showed that the only product of the combustion was carbon dioxide, proving that diamond is composed of carbon. Later, in 1797, the English chemist Smithson Tennant repeated and expanded that experiment. By demonstrating that burning diamond and graphite releases the same amount of gas, he established the chemical equivalence of these substances.

See also

Citations

- Warr LN (2021). "IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols". Mineralogical Magazine. 85 (3): 291–320. Bibcode:2021MinM...85..291W. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.43. ISSN 0026-461X. S2CID 235729616.

- ^ "Diamond". Mindat. Archived from the original on May 6, 2009. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

- "Diamond". WebMineral. Archived from the original on January 7, 2019. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

- Delhaes P (2000). "Polymorphism of carbon". In Delhaes P (ed.). Graphite and precursors. Gordon & Breach. pp. 1–24. ISBN 978-90-5699-228-6.

- Pierson HO (2012). Handbook of carbon, graphite, diamond, and fullerenes: properties, processing, and applications. Noyes Publications. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-0-8155-1739-9.

- Angus JC (1997). "Structure and thermochemistry of diamond". In Paoletti A, Tucciarone A (eds.). The physics of diamond. IOS Press. pp. 9–30. ISBN 978-1-61499-220-2.

- ^ Rock PA (1983). Chemical Thermodynamics. University Science Books. pp. 257–260. ISBN 978-1-891389-32-0.

- Gray T (October 8, 2009). "Gone in a Flash". Popular Science. Archived from the original on March 7, 2020. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- Chen Y, Zhang L (2013). Polishing of diamond materials: mechanisms, modeling and implementation. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-1-84996-408-1.

- ^ Bundy P, Bassett WA, Weathers MS, Hemley RJ, Mao HK, Goncharov AF (1996). "The pressure-temperature phase and transformation diagram for carbon; updated through 1994". Carbon. 34 (2): 141–153. Bibcode:1996Carbo..34..141B. doi:10.1016/0008-6223(96)00170-4.

- Wang CX, Yang GW (2012). "Thermodynamic and kinetic approaches of diamond and related nanomaterials formed by laser ablation in liquid". In Yang G (ed.). Laser ablation in liquids: principles and applications in the preparation of nanomaterials. Pan Stanford. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-981-4241-52-6.

- Wang X, Scandolo S, Car R (October 2005). "Carbon phase diagram from ab initio molecular dynamics". Physical Review Letters. 95 (18): 185701. Bibcode:2005PhRvL..95r5701W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.185701. PMID 16383918.

- Correa AA, Bonev SA, Galli G (January 2006). "Carbon under extreme conditions: phase boundaries and electronic properties from first-principles theory". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (5): 1204–1208. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.1204C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0510489103. PMC 1345714. PMID 16432191.

- Bland E (January 15, 2010). "Diamond oceans possible on Uranus, Neptune". Discovery News. Archived from the original on March 11, 2012. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- Silvera I (2010). "Diamond: Molten under pressure". Nature Physics. 6 (1): 9–10. Bibcode:2010NatPh...6....9S. doi:10.1038/nphys1491. S2CID 120836330. Archived from the original on July 30, 2022. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- Rajendran V (2004). Materials science. Tata McGraw-Hill Pub. p. 2.16. ISBN 978-0-07-058369-6.

- ^ Ashcroft NW, Mermin ND (1976). Solid state physics. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-03-083993-1.

- Bandosz TJ, Biggs MJ, Gubbins KE, Hattori Y, Iiyama T, Kaneko T, Pikunic J, Thomson K (2003). "Molecular models of porous carbons". In Radovic LR (ed.). Chemistry and physics of carbon. Vol. 28. Marcel Dekker. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-0-8247-0987-7.

- Webster R, Read PG (2000). Gems: Their sources, descriptions and identification (5th ed.). Great Britain: Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7506-1674-4.

- ^ Cartigny P, Palot M, Thomassot E, Harris JW (May 30, 2014). "Diamond Formation: A Stable Isotope Perspective". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 42 (1): 699–732. Bibcode:2014AREPS..42..699C. doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-042711-105259.

- Fukura S, Nakagawa T, Kagi H (November 2005). "High spatial resolution photoluminescence and Raman spectroscopic measurements of a natural polycrystalline diamond, carbonado". Diamond and Related Materials. 14 (11–12): 1950–1954. Bibcode:2005DRM....14.1950F. doi:10.1016/j.diamond.2005.08.046.

- Mohammad G, Siddiquei MM, Abu El-Asrar AM (2006). "Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase mediates diabetes-induced retinal neuropathy". Mediators of Inflammation. 2013 (2): 510451. arXiv:physics/0608014. Bibcode:2006ApJ...653L.153G. doi:10.1086/510451. PMC 3857786. PMID 24347828. S2CID 59405368.

- "Diamonds from Outer Space: Geologists Discover Origin of Earth's Mysterious Black Diamonds". National Science Foundation. January 8, 2007. Archived from the original on December 9, 2007. Retrieved October 28, 2007.

- "Diamonds Are Indestructible, Right?". Dominion Jewelers. December 16, 2015. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- Seal M (November 25, 1958). "The abrasion of diamond". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 248 (1254): 379–393. Bibcode:1958RSPSA.248..379S. doi:10.1098/rspa.1958.0250.

- Weiler HD (April 13, 2021) . "The wear and care of records and styli". Archived from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved August 25, 2024 – via Shure Applications Engineering.

- Neves AJ, Nazaré MH (2001). Properties, Growth and Applications of Diamond. Institution of Engineering and Technology. pp. 142–147. ISBN 978-0-85296-785-0. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- Boser U (2008). "Diamonds on Demand". Smithsonian. Vol. 39, no. 3. pp. 52–59. Archived from the original on March 2, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2009.

- ^ Read PG (2005). Gemmology. Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 165–166. ISBN 978-0-7506-6449-3. Archived from the original on November 9, 2023. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ Hazen RM (1999). The diamond makers. Cambridge University Press. pp. 7–10. ISBN 978-0-521-65474-6.

- O'Donoghue M (1997). Synthetic, Imitation and Treated Gemstones. Gulf Professional. pp. 34–37. ISBN 978-0-7506-3173-0.

- Lee J, Novikov NV (2005). Innovative superhard materials and sustainable coatings for advanced manufacturing. Springer. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-8493-3512-9.

- Marinescu ID, Tönshoff HK, Inasaki I (2000). Handbook of ceramic grinding and polishing. William Andrew. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8155-1424-4.

- ^ Harlow GE (1998). The nature of diamonds. Cambridge University Press. pp. 223, 230–249. ISBN 978-0-521-62935-5.

- Eremets MI, Trojan IA, Gwaze P, Huth J, Boehler R, Blank VD (October 3, 2005). "The strength of diamond". Applied Physics Letters. 87 (14): 141902. Bibcode:2005ApPhL..87n1902E. doi:10.1063/1.2061853.

- ^ Dubrovinsky L, Dubrovinskaia N, Prakapenka VB, Abakumov AM (October 23, 2012). "Implementation of micro-ball nanodiamond anvils for high-pressure studies above 6 Mbar". Nature Communications. 3 (1): 1163. Bibcode:2012NatCo...3.1163D. doi:10.1038/ncomms2160. PMC 3493652. PMID 23093199.

- ^ Wogan T (November 2, 2012). "Improved diamond anvil cell allows higher pressures than ever before". Physics World. Nature Communications. Archived from the original on January 2, 2018. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- Dang C, Chou JP, Dai B, Chou CT, Yang Y, Fan R, et al. (January 2021). "Achieving large uniform tensile elasticity in microfabricated diamond". Science. 371 (6524): 76–78. Bibcode:2021Sci...371...76D. doi:10.1126/science.abc4174. PMID 33384375. S2CID 229935085.

- Banerjee A, Bernoulli D, Zhang H, Yuen MF, Liu J, Dong J, et al. (April 2018). "Ultralarge elastic deformation of nanoscale diamond". Science. 360 (6386): 300–302. Bibcode:2018Sci...360..300B. doi:10.1126/science.aar4165. PMID 29674589. S2CID 5047604.

- LLorca J (April 2018). "On the quest for the strongest materials". Science. 360 (6386): 264–265. arXiv:2105.05099. Bibcode:2018Sci...360..264L. doi:10.1126/science.aat5211. PMID 29674578. S2CID 4986592.

- Collins AT (1993). "The Optical and Electronic Properties of Semiconducting Diamond". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 342 (1664): 233–244. Bibcode:1993RSPTA.342..233C. doi:10.1098/rsta.1993.0017. S2CID 202574625.

- Landstrass MI, Ravi KV (1989). "Resistivity of chemical vapor deposited diamond films". Applied Physics Letters. 55 (10): 975–977. Bibcode:1989ApPhL..55..975L. doi:10.1063/1.101694.

- Zhang W, Ristein J, Ley L (October 2008). "Hydrogen-terminated diamond electrodes. II. Redox activity". Physical Review E. 78 (4 Pt 1): 041603. Bibcode:2008PhRvE..78d1603Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.78.041603. PMID 18999435.

- Shi Z, Dao M, Tsymbalov E, Shapeev A, Li J, Suresh S (October 2020). "Metallization of diamond". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (40): 24634–24639. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11724634S. doi:10.1073/pnas.2013565117. PMC 7547227. PMID 33020306.

- Irving M (April 28, 2022). "Two-inch diamond wafers could store a billion Blu-Ray's worth of data". New Atlas. Retrieved April 29, 2022.

- Wissner-Gross AD, Kaxiras E (August 2007). "Diamond stabilization of ice multilayers at human body temperature" (PDF). Physical Review E. 76 (2 Pt 1): 020501. Bibcode:2007PhRvE..76b0501W. doi:10.1103/physreve.76.020501. PMID 17929997. S2CID 44344503. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 24, 2011.

- Fujimoto A, Yamada Y, Koinuma M, Sato S (June 2016). "Origins of sp(3)C peaks in C1s X-ray Photoelectron Spectra of Carbon Materials". Analytical Chemistry. 88 (12): 6110–6114. doi:10.1021/acs.analchem.6b01327. PMID 27264720.

- Bauer M (2012). Precious Stones. Vol. 1. Dover Publications. pp. 115–117. ISBN 978-0-486-15125-0.

- "Diamond Care and Cleaning Guide". Gemological Institute of America. Archived from the original on August 1, 2019. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- Jones C (August 27, 2016). "Diamonds are Flammable! How to Safeguard Your Jewelry". DMIA. Archived from the original on August 1, 2019. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- Baird CS. "Can you light diamond on fire?". Science Questions with Surprising Answers. Archived from the original on August 1, 2019. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- Lederle F, Koch J, Hübner EG (February 21, 2019). "Colored Sparks". European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry. 2019 (7): 928–937. doi:10.1002/ejic.201801300. S2CID 104449284.

- Collins AT, Kanda H, Isoya J, Ammerlaan CA, Van Wyk JA (1998). "Correlation between optical absorption and EPR in high-pressure diamond grown from a nickel solvent catalyst". Diamond and Related Materials. 7 (2–5): 333–338. Bibcode:1998DRM.....7..333C. doi:10.1016/S0925-9635(97)00270-7.

- Zaitsev AM (2000). "Vibronic spectra of impurity-related optical centers in diamond". Physical Review B. 61 (19): 12909–12922. Bibcode:2000PhRvB..6112909Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.61.12909.

- Walker J (1979). "Optical absorption and luminescence in diamond" (PDF). Reports on Progress in Physics. 42 (10): 1605–1659. Bibcode:1979RPPh...42.1605W. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.467.443. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/42/10/001. S2CID 250857323. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 6, 2015.

- Hounsome LS, Jones R, Shaw MJ, Briddon PR, Öberg S, Briddon P, Öberg S (2006). "Origin of brown coloration in diamond". Physical Review B. 73 (12): 125203. Bibcode:2006PhRvB..73l5203H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.73.125203.

- Wise RW (2001). Secrets Of The Gem Trade, The Connoisseur's Guide To Precious Gemstones. Brunswick House Press. pp. 223–224. ISBN 978-0-9728223-8-1.

- Khan U (December 10, 2008). "Blue-grey diamond belonging to King of Spain has sold for record 16.3 GBP". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- Nebehay S (May 12, 2009). "Rare blue diamond sells for record $9.5 million". Reuters. Archived from the original on May 16, 2009. Retrieved May 13, 2009.

- Pomfret J (December 1, 2009). "Vivid pink diamond sells for record $10.8 million". Reuters. Archived from the original on December 2, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- Cowing MD (2014). "Objective ciamond clarity grading" (PDF). Journal of Gemmology. 34 (4): 316–332. doi:10.15506/JoG.2014.34.4.316. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- Wang W, Cai L (September 2019). "Inclusion extraction from diamond clarity images based on the analysis of diamond optical properties". Optics Express. 27 (19): 27242–27255. Bibcode:2019OExpr..2727242W. doi:10.1364/OE.27.027242. PMID 31674589. S2CID 203141270.

- "Fact Checking Diamond Fluorescence: 11 Myths Dispelled". GIA 4Cs. March 27, 2018. Archived from the original on March 24, 2022. Retrieved June 6, 2022.

- Wei L, Kuo PK, Thomas RL, Anthony TR, Banholzer WF (June 1993). "Thermal conductivity of isotopically modified single crystal diamond". Physical Review Letters. 70 (24): 3764–3767. Bibcode:1993PhRvL..70.3764W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.70.3764. PMID 10053956.

- ^ Erlich EI, Hausel WD (2002). Diamond deposits: origin, exploration, and history of discovery. Littleton, CO: Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration. ISBN 978-0-87335-213-0.

- ^ Shirey SB, Shigley JE (December 1, 2013). "Recent Advances in Understanding the Geology of Diamonds". Gems & Gemology. 49 (4): 188–222. doi:10.5741/GEMS.49.4.188.

- Carlson RW (2005). The Mantle and Core. Elsevier. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-08-044848-0. Archived from the original on November 9, 2023. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- Deutsch A, Masaitis VL, Langenhorst F, Grieve RA (2000). "Popigai, Siberia—well preserved giant impact structure, national treasury, and world's geological heritage". Episodes. 23 (1): 3–12. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/2000/v23i1/002.

- King H (2012). "How do diamonds form? They don't form from coal!". Geology and Earth Science News and Information. geology.com. Archived from the original on October 30, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- Pak-Harvey A (October 31, 2013). "10 common scientific misconceptions". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Pohl WL (2011). Economic Geology: Principles and Practice. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-9486-3.

- Allaby M (2013). "mobile belt". A dictionary of geology and earth sciences (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-174433-4.

- Kjarsgaard BA (2007). "Kimberlite pipe models: significance for exploration" (PDF). In Milkereit B (ed.). Proceedings of Exploration 07: Fifth Decennial International Conference on Mineral Exploration. Decennial Mineral Exploration Conferences, 2007. pp. 667–677. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 24, 2012. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ Deep Carbon Observatory (2019). Deep Carbon Observatory: A Decade of Discovery. Washington, DC. doi:10.17863/CAM.44064. Archived from the original on December 17, 2019. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Cartier K (April 2, 2018). "Diamond Impurities Reveal Water Deep Within the Mantle". Eos. 99. doi:10.1029/2018EO095949.

- Perkins S (March 8, 2018). "Pockets of water may lie deep below Earth's surface". Science. Archived from the original on March 8, 2018. Retrieved June 30, 2022.