A text editor is a type of computer program that edits plain text. An example of such program is "notepad" software (e.g. Windows Notepad). Text editors are provided with operating systems and software development packages, and can be used to change files such as configuration files, documentation files and programming language source code.

Plain text and rich text

Main articles: Plain text and Rich textThere are important differences between plain text (created and edited by text editors) and rich text (such as that created by word processors or desktop publishing software).

Plain text exclusively consists of character representation. Each character is represented by a fixed-length sequence of one, two, or four bytes, or as a variable-length sequence of one to four bytes, in accordance to specific character encoding conventions, such as ASCII, ISO/IEC 2022, Shift JIS, UTF-8, or UTF-16. These conventions define many printable characters, but also non-printing characters that control the flow of the text, such as space, line break, and page break. Plain text contains no other information about the text itself, not even the character encoding convention employed. Plain text is stored in text files, although text files do not exclusively store plain text. Since the early days of computers, plain text was (once by necessity and now by convention) generally displayed using a monospace font, such that horizontal alignment and columnar formatting were sometimes done using whitespace characters.

Rich text, on the other hand, may contain metadata, character formatting data (e.g. typeface, size, weight and style), paragraph formatting data (e.g. indentation, alignment, letter and word distribution, and space between lines or other paragraphs), and page specification data (e.g. size, margin and reading direction). Rich text can be very complex. Rich text can be saved in binary format (e.g. DOC), text files adhering to a markup language (e.g. RTF or HTML), or in a hybrid form of both (e.g. Office Open XML).

Text editors are intended to open and save text files containing either plain text or anything that can be interpreted as plain text, including the markup for rich text or the markup for something else (e.g. SVG).

History

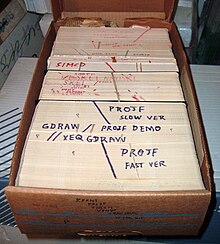

Before text editors existed, computer text was punched into cards with keypunch machines. Physical boxes of these thin cardboard cards were then inserted into a card reader. Magnetic tape, drum and disk card image files created from such card decks often had no line-separation characters at all, and assumed fixed-length 80- or 90-character records. An alternative to cards was Punched tape. It could be created by some teleprinters (such as the Teletype), which used special characters to indicate ends of records. Some early operating systems included batch text editors, either integrated with language processors or as separate utility programs; one early example was the ability to edit SQUOZE source files for SCAT in the SHARE Operating System.

The first interactive text editors were "line editors" oriented to teleprinter- or typewriter-style terminals without displays. Commands (often a single keystroke) effected edits to a file at an imaginary insertion point called the "cursor". Edits were verified by typing a command to print a small section of the file, and periodically by printing the entire file. In some line editors, the cursor could be moved by commands that specified the line number in the file, text strings (context) for which to search, and eventually regular expressions. Line editors were major improvements over keypunching. Some line editors could be used by keypunch; editing commands could be taken from a deck of cards and applied to a specified file. Some common line editors supported a "verify" mode in which change commands displayed the altered lines.

When computer terminals with video screens became available, screen-based text editors (sometimes called just "screen editors") became common. One of the earliest full-screen editors was O26, which was written for the operator console of the CDC 6000 series computers in 1967. Another early full-screen editor was vi. Written in the 1970s, it is still a standard editor on Unix and Linux operating systems. Also written in the 1970s was the UCSD Pascal Screen Oriented Editor, which was optimized both for indented source code and general text. Emacs, one of the first free and open-source software projects, is another early full-screen or real-time editor, one that was ported to many systems. The 1977 Commodore PET was the first mass-market computer to feature a full-screen editor. A full-screen editor's ease-of-use and speed (compared to the line-based editors) motivated many early purchases of video terminals.

The core data structure in a text editor is the one that manages the string (sequence of characters) or list of records that represents the current state of the file being edited. While the former could be stored in a single long consecutive array of characters, the desire for text editors that could more quickly insert text, delete text, and undo/redo previous edits led to the development of more complicated sequence data structures. A typical text editor uses a gap buffer, a linked list of lines (as in PaperClip), a piece table, or a rope, as its sequence data structure.

Types of text editors

Some text editors are small and simple, while others offer broad and complex functions. For example, Unix and Unix-like operating systems have the pico editor (or a variant), but many also include the vi and Emacs editors. Microsoft Windows systems come with the simple Notepad, though many people—especially programmers—prefer other editors with more features. Under Apple Macintosh's classic Mac OS there was the native TeachText later replaced by SimpleText in 1994, which was replaced in Mac OS X by TextEdit, which combines features of a text editor with those typical of a word processor such as rulers, margins and multiple font selection. These features are not available simultaneously, but must be switched by user command, or through the program automatically determining the file type.

Most word processors can read and write files in plain text format, allowing them to open files saved from text editors. Saving these files from a word processor, however, requires ensuring the file is written in plain text format, and that any text encoding or BOM settings will not obscure the file for its intended use. Non-WYSIWYG word processors, such as WordStar, are more easily pressed into service as text editors, and in fact were commonly used as such during the 1980s. The default file format of these word processors often resembles a markup language, with the basic format being plain text and visual formatting achieved using non-printing control characters or escape sequences. Later word processors like Microsoft Word store their files in a binary format and are almost never used to edit plain text files.

Some text editors can edit unusually large files such as log files or an entire database placed in a single file. Simpler text editors may just read files into the computer's main memory. With larger files, this may be a slow process, and the entire file may not fit. Some text editors do not let the user start editing until this read-in is complete. Editing performance also often suffers in nonspecialized editors, with the editor taking seconds or even minutes to respond to keystrokes or navigation commands. Specialized editors have optimizations such as only storing the visible portion of large files in memory, improving editing performance.

Some editors are programmable, meaning, e.g., they can be customized for specific uses. With a programmable editor it is easy to automate repetitive tasks or, add new functionality or even implement a new application within the framework of the editor. One common motive for customizing is to make a text editor use the commands of another text editor with which the user is more familiar, or to duplicate missing functionality the user has come to depend on. Software developers often use editor customizations tailored to the programming language or development environment they are working in. The programmability of some text editors is limited to enhancing the core editing functionality of the program, but Emacs can be extended far beyond editing text files—for web browsing, reading email, online chat, managing files or playing games and is often thought of as a Lisp execution environment with a Text User Interface. Emacs can even be programmed to emulate Vi, its rival in the traditional editor wars of Unix culture.

An important group of programmable editors uses REXX as a scripting language. These "orthodox editors" contain a "command line" into which commands and macros can be typed and text lines into which line commands and macros can be typed. Most such editors are derivatives of ISPF/PDF EDIT or of XEDIT, IBM's flagship editor for VM/SP through z/VM. Among them are THE, KEDIT, X2, Uni-edit, and SEDIT.

A text editor written or customized for a specific use can determine what the user is editing and assist the user, often by completing programming terms and showing tooltips with relevant documentation. Many text editors for software developers include source code syntax highlighting and automatic indentation to make programs easier to read and write. Programming editors often let the user select the name of an include file, function or variable, then jump to its definition. Some also allow for easy navigation back to the original section of code by storing the initial cursor location or by displaying the requested definition in a popup window or temporary buffer. Some editors implement this ability themselves, but often an auxiliary utility like ctags is used to locate the definitions.

Typical features

- Find and replace – Text editors provide extensive facilities for searching and replacing strings of text, either individually, or groups of files in opened tabs or a selected folder. Advanced editors can use regular expressions to search and edit text or code. Additional features may include optional case sensitivity, a history of search terms for quick recall and autocompletion, and listing multiple results in one place.

- Cut, copy, and paste – most text editors provide methods to duplicate and move text within the file, or between files.

- Ability to handle UTF-8 encoded text.

- Text formatting – Text editors often provide basic visual formatting features like line wrap, auto-indentation, bullet list formatting using ASCII characters, comment formatting, syntax highlighting and so on. These are typically only for display and do not insert formatting codes into the file itself.

- Undo and redo – As with word processors, text editors provide a way to undo and redo the last edit, or more. Often—especially with older text editors—there is only one level of edit history remembered and successively issuing the undo command will only "toggle" the last change. Modern or more complex editors usually provide a multiple-level history such that issuing the undo command repeatedly will revert the document to successively older edits. A separate redo command will cycle the edits "forward" toward the most recent changes. The number of changes remembered depends upon the editor and is often configurable by the user.

- Ability to jump to a specified line number.

Advanced features

- Macro or procedure definition: to define new commands or features as combinations of prior commands or other macros, perhaps with passed parameters, or with nesting of macros.

- Profiles to retain options set by the user between editing session.

- Profile macros with names specified in, e.g., environment, profile, executed automatically at the beginning of an edit session or when opening a new file.

- Multi-file editing: the ability to edit multiple files during an edit-session, perhaps remembering the current-line cursor of each file, to insert repeated text into each file, copy or move text among files, compare files side-by-side (perhaps with a tiled multiple-document interface), etc.

- Multi-view editors: the ability to display multiple views of the same file, with independent cursor tracking, synchronizing changes among the windows but providing the same facilities as are available for independent files.

- Collapse/expand, also called folding: the ability to temporarily exclude sections of the text from view. This may either be based on a range of line numbers or on some syntactic element, e.g., excluding everything between a BEGIN; and the matching END;.

- Column-based editing; the ability to alter or insert data at a particular column, or to shift data to specific columns.

- Data transformation – Reading or merging the contents of another text file into the file currently being edited. Some text editors provide a way to insert the output of a command issued to the operating system's shell. Also, a case-shifting feature could translate to lowercase or uppercase.

- Filtering – Some advanced text editors allow the editor to send all or sections of the file being edited to another utility and read the result back into the file in place of the lines being "filtered". This, for example, is useful for sorting a series of lines alphabetically or numerically, doing mathematical computations, indenting source code, and so on.

- Syntax highlighting – contextually highlights source code, markup languages, config files and other text that appears in an organized or predictable format. Editors generally allow users to customize the colors or styles used for each language element. Some text editors also allow users to install and use themes to change the look and feel of the editor's entire user interface.

- Syntax-oriented editors - some editors have support for the syntax of one or more languages, and allow operations in terms of syntactical unit, e.g., insert a new WHEN clause in a SELECT statement.

- Extensibility - a text editor intended for use by programmers must provide some plugin mechanism, or be scriptable, so a programmer can customize the editor with features needed to manage individual software projects, customize functionality or key bindings for specific programming languages or version control systems, or conform to specific coding styles.

- Cursor navigation may vary across text editors. For example, pressing End twice may navigate to the end of a wrapped line after one press navigated to the end of an on-screen row of text. Block-oriented terminals typically have dedicated cursor movement keys, as do keyboards on personal computers.

- Command line - some editors, e.g., ISPF, XEDIT, have a dedicated field on the screen for entering commands as opposed to text. Depending on the editor, the user may have to use cursor keys to switch between the command and text fields or the editor may interpret, e.g., specific function keys , as requests to switch.

- Line commands, also known as prefix commands or sequence commands - Some editors treat a file as an array of text lines with associated line numbers or sequence numbers, and have a distinct line number field for each text field. A line command is a string that the user types into a line number field and that the editor recognizes as a command operating on that specific line or block of lines, e.g., LC to translate a line to lower case, ))3 to shift a block right three columns. Some editors also support line macros, also known as prefix macros or sequence macros. Despite the name prefix command, some editors allow the sequence field to appear after the text field.

- Text editors, especially source-code editors, often default to using a monospace font that clearly distinguishes between similar characters (homoglyphs) such as the colon and the semicolon.

Specialized editors

Some editors include special features and extra functions, for instance,

- Source code editors are text editors with additional functionality to facilitate the production of source code. These often feature user-programmable syntax highlighting and code navigation functions as well as coding tools or keyboard macros similar to an HTML editor.

- Folding editors. This subclass includes so-called "orthodox editors" that are derivatives of Xedit. Editors that implement folding without programing-specific features are usually called outliners (see below).

- Outliners. Also called tree-based editors, because they combine a hierarchical outline tree view with a text editor. Folding (see above) can be considered a specialized form of outlining.

- IDEs (integrated development environments) are designed to manage and streamline large programming projects. They are usually only used for programming as they contain many features unnecessary for simple text editing.

- World Wide Web authors are offered a variety of HTML editors dedicated to the task of creating web pages. These include: Dreamweaver, KompoZer and E Text Editor. Many offer the option of viewing a work in progress on a built-in HTML rendering engine or standard web browser. However, most web development is done in a dynamic programming language such as Ruby or PHP using a source code editor or IDE. The HTML delivered by all but the simplest static web sites is stored as individual template files that are assembled by the software controlling the site and do not compose a complete HTML document.

- Mathematicians, physicists, and computer scientists often produce articles and books using TeX or LaTeX in plain text files. Such documents are often produced by a standard text editor, but some people use specialized TeX editors.

- Collaborative editors allow multiple users to work on the same document simultaneously from remote locations over a network. The changes made by individual users are tracked and merged into the document automatically to eliminate the possibility of conflicting edits. These editors also typically include an online chat component for discussion among editors.

- Distraction-free editors provide a minimalistic interface with the purpose of isolating the writer from the rest of the applications and operating system, thus being able to focus on the writing without distractions from interface elements like a toolbar or notification area.

Programmable editors can usually be enhanced to perform any or all of these functions, but simpler editors focus on just one, or, like gPHPedit, are targeted at a single programming language.

See also

- List of text editors

- Comparison of text editors

- Editor war

- File viewer – does not change file, faster for very large files and can be more secure

- Hex editor – used for editing binary files

- Stream editor – used for non-interactive editing

- Structure editor – any document editor that is cognizant of the document's underlying structure

- WYSIWYG – an acronym for What You See Is What You Get

- Visual editor – computer software for editing text files using a textual or graphical user interface

Notes

- By the late 1960s editors were available that supported variable-length records.

- Originally macros were written in assembler, CLIST (TSO), CMS EXEC (VM), EXEC2 (VM/SE) or PL/I, but most users dropped CLIST, EXEC and EXEC2 once REXX was available.

- A line command is a command typed into the sequence number entry area associated with a specific line of text and whose scope is limited to that line, or, in the case of a block command, associated with the block of lines between the beginning and ending line commands. An example of the latter would be typing the command ucc (block upper case) into the entry areas of two lines; this has the same effect as typing uc (upper case) into the entry area of each line in the range.

References

- H. Albert Napier; Ollie N. Rivers; Stuart Wagner (2005). Creating a Winning E-Business. Cengage Learning. p. 330. ISBN 1111796092.

- Peter Norton; Scott H. Clark (2002). Peter Norton's New Inside the PC. Sams Publishing. p. 54. ISBN 0672322897.

- L. Gopalakrishnan; G. Padmanabhan; Sudhat Shukla (2003). Your Home PC: Making the Most of Your Personal Computer. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. p. 190. ISBN 0070473544.

- "The Best Free Text Editors for Windows, Linux, and Mac". 28 April 2012.

Every operating system comes with a default, basic text editor, but most of us install our own enhanced text editors to get more features.

- Louden, Kenneth C.; Lambert, Kenneth A. (2011-01-26). Programming Languages: Principles and Practices. Cengage Learning. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-133-38749-7.

- "UNIVAC 90-COLUMN PUNCHED 'CARD-TO-MAGNETIC TAPE CONVERTER" (PDF). UNIVAC II Data Automation System (PDF). Remington-Rand Univac Division of Sperry Rand Corporation. 1957. p. 246. Retrieved December 16, 2022.,

- Alavudeen, A.; Venkateshwaran, N. (2008-08-18). Computer Integrated Manufacturing. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. p. 180. ISBN 978-81-203-3345-1.

- Upton, Eben; Duntemann, Jeffrey; Roberts, Ralph; Mamtora, Tim; Everard, Ben (2016-08-22). Learning Computer Architecture with Raspberry Pi. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 232–234. ISBN 978-1-119-18394-5.

- "Modify and Load" (PDF). SOS Reference Manual (PDF). IBM. November 1959 . p. 05.01.01. Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- "The Open Group Base Specifications Issue 6, IEEE Std 1003.1, 2004 Edition". The IEEE and The Open Group. 2004. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- L. Bowles, Kenneth; Hollan, James (1978-07-01). "An introduction to the UCSD PASCAL system". Behavior Research Methods. 10 (4): 531–534. doi:10.3758/BF03205341.

- "Introducing the Emacs editing environment". IBM. Archived from the original on 2014-06-06. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- "Multics Emacs: The History, Design and Implementation".

Some Multics users purchased these terminals ..., using them either as "glass teletypes" or via "local editing."

- Charles Crowley. "Data Structures for Text Sequences". Section "Introduction".

- "Text Editors for Programmeres - Programming Tools".

If you open a .doc file in a text editor, you will notice that most of the file is formatting codes. Text editors, however, do not add formatting codes, which makes it easier to compile your code.

- "Vim to Emacs' Evil chaotic migration guide". juanjoalvarez.net. 19 September 2014.

- "Gitorious". Archived from the original on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- "Searching". Notepad++ User Manual. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- Philipp Acsany. "Choosing the Best Coding Font for Programming". 2023.

External links

- Orthodox Editors as a Special Class of Advanced Editors, discusses Xedit and its clones with an emphasis of folding capabilities and programmability