| Dragon Dance | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 舞龍 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 舞龙 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 弄龍 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

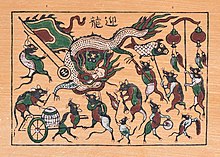

Dragon dance (simplified Chinese: 舞龙; traditional Chinese: 舞龍; pinyin: wǔ lóng; Jyutping: mou5 lung4) is a form of traditional dance and performance in Chinese culture. Like the lion dance, it is most often seen during festive celebrations. The dance is performed by a team of experienced dancers who manipulate a long flexible giant puppet of a dragon using poles positioned at regular intervals along the length of the dragon. The dance team simulates the imagined movements of this mythological creature in a sinuous, undulating manner.

The dragon dance is often performed during Chinese New Year. The Chinese dragon is a symbol of China's culture, and it is believed to bring good luck to people, therefore the longer the dragon is in the dance, the more luck it will bring to the community. The dragons are believed to possess qualities that include great power, dignity, fertility, wisdom and auspiciousness. The appearance of a dragon is both fearsome and bold but it has a benevolent disposition, and it was an emblem to represent imperial authority. The movements in a performance traditionally symbolize the power and dignity of the dragon.

History

During the Han dynasty, different forms of the dragon dance were described in ancient texts. Rain dance performed at times of drought may involve the use of figures of dragon as Chinese dragon was associated with rain in ancient China, for example the dragon Yinglong was considered a rain deity, and the Shenlong had the power to determine how much wind and rain to bring. According to the Han dynasty text Luxuriant Dew of the Spring and Autumn Annals by Dong Zhongshu, as part of a ritual to appeal for rain, clay figures of the dragons were made and children or adults may then perform a dance. The number of dragons, their length and color, as well as the performers may vary according to the time of year. Other dances involving dragons may be found in a popular form of entertainment during the Han dynasty, the baixi (百戲) variety shows, where performers called "mime people" (象人) dressed up as various creatures such as beasts, fish and dragons. In his Lyric Essay on Western Capital (西京賦) Zhang Heng recorded various performances such as performers who dressed as a green dragon playing a flute, and a fish-dragon act where fish transformed into a dragon. A version of the fish-dragon dance called "fish-dragon extending" (魚龍曼延) was also performed at the Han court to entertain foreign guests – in this dance a mythical beast of Shenli (舍利之獸) transforms into flounder, then to a dragon. These ancient dances however do not resemble modern Dragon Dance in their descriptions, and depictions of dragon dance in Han dynasty stone relief engravings suggest that the props used may also be cumbersome, unlike modern Dragon Dance where light-weight dragons are manipulated by performers.

The dragon acts of the Han dynasty were also mentioned in the Tang and Song dynasty. Figures similar to the dragon lantern (龍燈) used during Lantern Festival were described in the Song dynasty work Dreams of Splendor of the Eastern Capital, where figures of dragon mounted for display were constructed out of grass and cloth and inside which numerous candle lights may be placed. Such dragon lanterns may also be carried and paraded by performers in the street during the Lantern festival at nighttime. A wide variety of dragon dances have developed in various regions in China, for example, the Fenghua Cloth Dragon (奉化布龙) from Zhejiang was made with bamboo frame and covered with cloth, and is said to have been developed in the 1200s. A form of dragon dance from Tongliang County (铜梁龙舞), which originated as snake totem worship, began during the Ming dynasty and became popular in the Qing dynasty. In the modern era, the government of People's Republic of China adapted and promoted various traditional folk dances, which contributed to the popularity of the current form of the dragon dance now found widely in China as well as Chinese communities around the world.

Aside from the popular form of dragon dance, other regional dragon dances include one from Zhanjiang, Guangdong province whereby the body of the dragon is formed entirely of a human chain of dozens to hundreds of performers, and in Pujiang County, Zhejiang Province, the body of the dragon is formed using wooden stools. The number of different dragon dances has been put at over 700.

Typically, retired dragons are burned and not saved. The head of the oldest surviving dragon, dating back to 1878 and named Moo Lung, is preserved and on display at the Bok Kai Temple in Marysville, California. Other fragments of dragons of similar age are kept at the Sweetwater County Historical Museum in Green River, Wyoming (1893, eyes only), Gold Museum in Ballarat (1897, head only), and the Golden Dragon Museum in Bendigo (1901, the oldest complete dragon, named Loong). Bendigo's Loong was used regularly in that city's Easter parade until 1970, and occasionally has come out of storage since then to welcome newer dragons to Bendigo.

Dragon structure

The dragon is a long serpentine body formed of a number of sections on poles, with a dragon head and a tail. The dragon is assembled by joining the series of hoops on each section and attaching the ornamental head and tail pieces at the ends. Traditionally, dragons were constructed of wood, with bamboo hoops on the inside and covered with a rich fabric, however in the modern era lighter materials such as aluminium and plastics have replaced the wood and heavy material.

Dragons can range in length from as little as 2 metres (10 ft) operated by two people for small displays, around 25 to 35 metres (80 to 110 ft) for the more acrobatic models, and up to 50 to 70 metres (160 to 230 ft) for the larger parade and ceremonial styles. The size and length of a dragon depends on the human power available, financing, materials, skills and size of the field. A small organization cannot afford to run a very long dragon because it requires considerable human power, great expense and special skills.

The normal length and size of the body recommended for the dragon is 34 metres (110 ft) and is divided into nine major sections. The distance of each minor (rib-like) section is 35 cm (14 in) apart; therefore, the body has 81 rings. Many may also be up to 15 sections long, and some dragons are as long as 46 sections. Occasionally, dragons with far more sections may be constructed in Chinese communities around the world to produce the longest dragon possible, since part of the myth of the dragon is that the longer the creature, the more luck it will bring. Sun Loong in Bendigo, Australia was, at the time it was made in 1970, the longest dragon in the world measuring approximately 100 metres (330 ft) and is believed to be the longest regularly used dragon. Much longer dragons have been created for one-off events. The world record for the longest dragon is 5,605 metres (18,390 ft), set in Hong Kong on 1 October 2012.

Historically the dragon dance may be performed in a variety of ways with different types and colours of dragon. Green is sometimes selected as a main colour of the dragon, which symbolizes a great harvest. Other colours include: yellow, symbolizing the solemn empire; gold or silver, symbolizing prosperity; red, representing excitement. The dragon's scales and tail are mostly beautiful silvery and glittery to create a joyous atmosphere. As the dragon dance is not performed every day, the cloth of the dragon is removed and touched up with ultra-paint before each performance.

Performance

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The dragon dance is performed by a skilled team whose job is to bring the motionless puppet body to life. The correct combination and proper timing of the different parts of the dragon are very important to make a successful dance. Any mistakes made by even some of the performers would spoil the whole performance. To be very successful in the dance, the head of the Dragon must be able to coordinate with the body movement to match the timing of the drum. For larger ceremonial and parade style dragons, the head can weigh as much as 12 katis (14.4 kg, almost 32 lb). The dragon tail also has an important role to play as it will have to keep in time with head movements. The fifth section is considered to be the middle portion and the performers must be very alert as the body movements change from time to time. The dragon is often led by a person holding a spherical object representing a pearl.

The patterns of the dragon dance are choreographed according to the skills and experiences acquired by the performers. Some of the patterns of the dragon dance are "Cloud Cave", "Whirlpool", tai chi pattern, "threading the money", "looking for pearl", and "dragon encircling the pillar". The movement "dragon chasing the pearl" shows that the dragon is continually in the pursuit of wisdom.

The dragon moves in a wave-like pattern achieved by the co-ordinated swinging of each section in succession. Whilst this swinging constitutes the basic movement of the dragon, executing more complex formations is only limited by a team's creativity. The patterns and tricks that are performed generally involve running into spiraled formations to make the dragon body turn and twist on itself. This causes performers to jump over or through the dragon's body sections, adding to the visual display. Other advanced manoeuvres include various corkscrew-like rotating tricks and more acrobatic moves where the performers stand on each other's legs and shoulders to increase the height of the dragon's movements.

Performing in a dragon dance team incorporates several elements and skills; it is something of a cross-over activity, combining the training and mentality of a sports team with the stagecraft and flair of a performing arts troupe. The basic skills are simple to learn, however to become a competent performer takes dedicated training until movements become second nature and complex formations can be achieved – which rely not only on the skill of the individual member, but on concentration by the team as a whole to move in co-operation.

A double dragon dance, rarely seen in Western exhibitions, involves two troupes of dancers intertwining the dragons. Even rarer are dances with the full array of nine dragons, since nine is a "perfect" number. Such dances involve large number of participants from various organizations, and are often only possible under the auspices of a regional or national government.

Competition

A number of dragon dance competitions have been organized around the world. In competition performances however, there are strict rules governing the specifications of the dragon body and the routine performed, and so dragons made for these events and what are mostly seen in the impressive stage shows are made for speed and agility, to be used by the performing team for maximum trick difficulty. In these dragons, the head is smaller and light enough to be whipped around, and must be a minimum of 3 kg, the body pieces are a light aluminium with cane and the majority of the hoops will be very thin PVC tubing. Performances are typically 8- to 10-minute routines with an accompanying percussion set.

In more recent times, luminous dragons whereby the dragons are painted with luminous paints that fluoresce under black light are also used in competition.

Outside China

The Chinese dragon is "perhaps the most recognized form of parade puppet". Unlike the lion dance in many Asian countries where there are numerous native versions of the dance, the dragon dance is found in other countries primarily among overseas Chinese communities. In Japan, the dragon dance (龍踊, Ja Odori or "Snake Dance" 蛇踊) is one of the main attractions in the Nagasaki Kunchi festival. The dance was originally performed by Chinese residents who settled in Nagasaki, the only port said to be open for foreign trade in Japan during the Edo period. The dragon dance has also been adapted for other local festivities by the Japanese – a golden dragon dance (金龍の舞, Kinryū no Mai) has been performed at the Sensō-ji in Tokyo since 1958. There is however a form that is unique to Japan – the Orochi (a great serpent or Japanese dragon) which may be found in a kagura performance.

In Vietnam, the dragon dance (múa rồng) may be performed during Tết, the Vietnamese Lunar New Year, as well as during Tết Trung Thu, the Vietnamese Mid-Autumn Festival. It is often referred to, collectively, as múa lân sư rồng (lion/qilin, monk, and dragon dance).

In Indonesia, the dragon dance is called liang liong.

In literature

Lawrence Ferlinghetti's poem "The Great Chinese Dragon", published in his 1961 anthology Starting from San Francisco, was inspired by the dragon dance. Gregory Stephenson says the dragon "... represents 'the force and mystery of life,' the true sight that 'sees the spiritual everywhere translucent in the material world'".

Earl Lovelace's 1979 novel The Dragon Can't Dance uses the theme of the Carnival dance to explore social change and history in the West Indies.

Arthur Ransome incorporates dragon dances in his children's book Missee Lee (1941), part of the Swallows and Amazons series, which is set in 1930s China.

See also

References

- ^ "Dragon Dance". Cultural China. Archived from the original on 2014-06-12.

- Lihui Yang, Deming An (2008). Handbook of Chinese Mythology. Oxford University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0195332636.

- Jeremy Roberts (2004). Chinese Mythology A to Z: [A Young Reader's Companion]. Facts on File. p. 31. ISBN 9780816048700.

- Lihui Yang, Deming An (2008). Handbook of Chinese Mythology. Oxford University Press. pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-0195332636.

- 《求雨》. Chinese Text Project.

- Richard Gunde (2001). Culture and Customs of China. Greenwood. p. 104. ISBN 978-0313361180.

- Faye Chunfang Fei, ed. (2002). Chinese Theories of Theater and Performance from Confucius to the Present. University of Michigan Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0472089239.

- 西京賦.

- 陈晓丹 (26 November 2013). 中国文化博览1.

- Wang Kefen (1985). The History of Chinese Dance. China Books & Periodicals. pp. 25–27. ISBN 978-0835111867.

- 宋代文化史. 知書房出版集團. 1995. p. 688. ISBN 9579086826.

- 東京夢華錄/卷六.

- Lihui Yang, Deming An (2008). Handbook of Chinese Mythology. Oxford University Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0195332636.

- "Dragon Dance". Confucius Institute Online. Archived from the original on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-11-03.

- Mary Ellen Snodgrass (8 August 2016). The Encyclopedia of World Folk Dance. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 80–81. ISBN 9781442257498.

- "Fenghua Cloth Dragon". Ningbo.China. 2009-07-23. Archived from the original on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-11-03.

- Luo Li (2014). Intellectual Property Protection of Traditional Cultural Expressions: Folklore in China. Springer. p. 141. ISBN 978-3319045245.

- Wang Kefen (1985). The History of Chinese Dance. China Books & Periodicals. p. 103. ISBN 978-0835111867.

- "A brief history of Zhanjiang Dragon's Dance". The Zhanjiang Travel & Tourism Portal. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2014-01-19.

- Janet Descutner (2010). Asian Dance. Chelsea House Publishing. p. 100. ISBN 978-1604134780.

- Potts, Billy (May 23, 2018). "Australia is saving a Hong Kong tradition". Zolima City. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Tom, Lawrence; Tom, Brian (2020). "5: The Marysville Dragons". Gold Country's Last Chinatown: Marysville, California. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press. pp. 68–80. ISBN 9781467143233. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Parade Dragon". Bok Kai Temple. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Chinese Dragon Eyes Selected as Finalist in Wyoming's Most Significant Artifact". Sweetwater Now. June 15, 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

The Chinese dragon eyes on display at the Sweetwater County Historical Museum in Green River have been selected as finalists in 'Wyoming's Most Significant Artifact' competition ...

- Evans, Anna (September 28, 2017). "Re-awakening the Dragon exhibit will feature array of rare Chinese artefacts". The Courier. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Ballarat Dragon". Culture Victoria. 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Cosoleto, Tara (April 19, 2019). "From Loong to Dai Gum Loong: the journey of Bendigo's Chinese dragons". Bendingo Advertiser. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Cosoleto, Tara (April 21, 2019). "Oldest imperial dragon Loong welcomes Bendigo's new dragon Dai Gum Loong". Bendingo Advertiser. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "BCA - Our Dragon Collection". Bendigochinese.org.au. Archived from the original on 2013-10-04. Retrieved 2013-08-24.

- Kevin Murray. "Bendigo's Year of the Dragon". Kitezh.com. Retrieved 2013-08-24.

- Worthington, Brett (2012-01-04). "Dragon has lived a long life". Bendigo Advertiser. Retrieved 2013-08-24.

- "Longest traditional Chinese dragon". Guinness World Records.

- Bell, Amanda (25 July 2019). "Chinese Dragon Head Stage Puppet". texancultures.utsa.edu. Texan Cultures. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- Lambeth, Cheralyn L. (2019). Introduction to Puppetry Arts. London: Routledge. p. 100. ISBN 978-1138336735.

- 蛇踊?龍踊?竜踊? その1. November 20, 2014.

- "Nagasaki Kunchi". Kids Web Japan.

- John Asano (4 October 2015). "Festivals of Japan: Nagasaki Kunchi Festival". GaijinPot.

- "Kinryu no mai (golden dragon dance)". Go Tokyo.

- "Kinryu no Mai (Golden Dragon Dance)". Ambassadors Japan. October 6, 2015.

- ""Iwami Kagura," a Traditional Autumn Festival in Shimane". Rikisha Amazing Asia. Archived from the original on 2016-08-08. Retrieved 2016-06-06.

- "Vietnamese Dragons". DragonsInn.net. 9 January 2021.

- "Ferlinghetti, Lawrence (Vol. 111) - Introduction". eNotes.com. Retrieved 2010-02-18.

- Daryl Cumber Dance (1986). Fifty Caribbean writers: a bio-bibliographical critical sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 282. ISBN 0-313-23939-8.

External links

| Chinese New Year | |

|---|---|

| Culture of China | |

| Topics | |

| Food | |

| Other | |

| Related | |

| Golden Week | |