This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Education in Germany is primarily the responsibility of individual German states (Länder), with the federal government only playing a minor role.

While kindergarten (nursery school) is optional, formal education is compulsory for all children ages 6 to 15. Students can complete three types of school leaving qualifications, ranging from the more vocational Hauptschulabschluss and Mittlere Reife over to the more academic Abitur. The latter permits students to apply to study at university level. A bachelor's degree is commonly followed up with a master's degree, with 45% of all undergraduates proceeding to postgraduate studies within 1.5 years of graduating. While rules vary (see → § Tuition fees) from Land (state) to Land, German public universities generally don't charge tuition fees.

Germany is well-known internationally for its vocational training model, the Ausbildung (apprenticeship), with about 50 per cent of all school leavers entering vocational training.

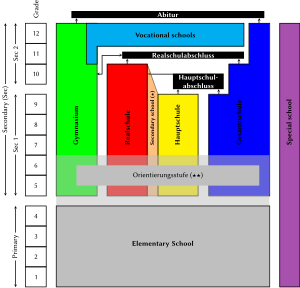

Secondary school forms

Germany's secondary education is separated into two parts, lower and upper. Germany's Lower-secondary education provides individuals with "basic general education", and gets them ready to enter upper-secondary education, which in turn usually allows vocational training. It's common to find mistranslations that say that this education is professional, while it is more accurately described as vocational. The German secondary education is then partitioned into five subtypes of schools: Gymnasium, Realschule, Hauptschule, Gesamtschule and Sonderschule.

One, the Gymnasium, is designed to prepare pupils for higher education and finishes with the final examination, Abitur, after grade 12 or 13. From 2005 to 2018 a school reform known as G8 provided the Abitur in 8 school years. The reform failed due to high demands on learning levels for the children and were turned to G9 in 2019. Only a few Gymnasiums stay with the G8 model. Children usually attend Gymnasium from 10 to 18 years.

The Realschule has a range of emphasis for intermediate pupils and finishes with the final examination Mittlere Reife, after grade 10; the Hauptschule prepares pupils for vocational education and finishes with the final examination Hauptschulabschluss, after grade 9 and the Realschulabschluss after grade 10. There are two types of grade 10: one is the higher level called type 10b and the lower level is called type 10a; only the higher-level type 10b can lead to the Realschule and this finishes with the final examination Mittlere Reife after grade 10b. This new path of achieving the Realschulabschluss at a vocationally oriented secondary school was changed by the statutory school regulations in 1981—with a one-year qualifying period. During the one-year qualifying period of the change to the new regulations, pupils could continue with class 10 to fulfil the statutory period of education. After 1982, the new path was compulsory, as explained above.

A less common secondary school alternative is the so-called Gesamtschule, i.e. comprehensive school. There are two main types of Gesamtschule, namely integriert (≈integrated) or kooperativ (≈collaborative ).

There are also Förder- or Sonderschulen, schools for students with special educational needs. One in 21 pupils attends a Förderschule. Nevertheless, the Förder- or Sonderschulen can also lead, in special circumstances, to a Hauptschulabschluss of both type 10a or type 10b, the latter of which is the Realschulabschluss. The amount of extracurricular activity is determined individually by each school and varies greatly. With the 2015 school reform the German government has tried to push more of those pupils into other schools, which is known as Inklusion. A special system of apprenticeship called Duale Ausbildung (the dual education system) allows pupils in vocational courses to do in-service training in a company as well as at a state school.

Students in Germany scored above the OECD average in reading (498 score points), mathematics (500) and science (503) in PISA 2018. Average reading performance in 2018 returned to levels that were last observed in 2009, reversing most gains up to 2012. In science, mean performance was below 2006 levels; while in mathematics PISA 2018 results lay significantly below those of the 2012 study. The Human Rights Measurement Initiative finds that Germany is achieving 75.4% of what should be possible for the right to education, at their level of income.

History

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (March 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Prussian

Main article: Prussian education systemHistorically, Lutheranism had a strong influence on German culture, including its education. Martin Luther advocated compulsory schooling so that all people would independently be able to read and interpret the Bible. This concept became a model for schools throughout Germany. German public schools generally have religious education provided by the churches in cooperation with the state ever since.

During the 18th century, the Kingdom of Prussia was among the first countries in the world to introduce free and generally compulsory primary education, consisting of an eight-year course of basic education,Volksschule. It provided not only the skills needed in an early industrialized world (reading, writing, and arithmetic) but also a strict education in ethics, duty, discipline and obedience. Children of affluent parents often went on to attend preparatory private schools for an additional four years, but the general population had virtually no access to secondary education and universities.

In 1810, during the Napoleonic Wars, Prussia introduced state certification requirements for teachers, which significantly raised the standard of teaching. The final examination, Abitur, was introduced in 1788, implemented in all Prussian secondary schools by 1812 and extended to all of Germany in 1871. The state also established teacher training colleges for prospective teachers in the common or elementary grades.

German Empire

When the German Empire was formed in 1871, the school system became more centralized. In 1872, Prussia recognized the first separate secondary schools for females. As learned professions demanded well-educated young people, more secondary schools were established, and the state claimed the sole right to set standards and to supervise the newly established schools.

Four different types of secondary schools developed:

- A nine-year classical Gymnasium (including study of Latin and Classical Greek or Hebrew, plus one modern language);

- A nine-year Realgymnasium (focusing on Latin, modern languages, science and mathematics);

- A nine-year Oberrealschule (focusing on modern languages, science and mathematics).

- A six-year Realschule (without university entrance qualification, but with the option of becoming a trainee in one of the modern industrial, office or technical jobs); and

By the turn of the 20th century, the four types of schools had achieved equal rank and privilege, although they did not have equal prestige.

Weimar Republic

After 1919, the Weimar Republic established a free, universal four-year elementary school (Grundschule). Most pupils continued at these schools for another four-year course. Those who were able to pay a small fee went on to a Mittelschule that provided a more challenging curriculum for an additional one or two years. Upon passing a rigorous entrance exam after year four, pupils could also enter one of the four types of secondary school.

Nazi Germany

See also: Nazi universityDuring the Nazi era (1933–1945), though the curriculum was reshaped to teach the beliefs of the regime, the basic structure of the education system remained unchanged.

East Germany

Main article: Education in East Germany| This section needs expansion with: Information on denazification policies for parity with subsequent FRG subsection. You can help by adding to it. (June 2023) |

The German Democratic Republic (East Germany) started its own standardized education system in the 1960s. The East German equivalent of both primary and secondary schools was the Polytechnic Secondary School (Polytechnische Oberschule), which all students attended for 10 years, from the ages of 6 to 16. At the end of the 10th year, an exit examination was set. Depending upon the results, a pupil could choose to come out of education or undertake an apprenticeship for an additional two years, followed by an Abitur. Those who performed very well and displayed loyalty to the ruling party could change to the Erweiterte Oberschule (extended high school), where they could take their Abitur examinations after 12 school years. Although this system was abolished in the early 1990s after reunification, it continues to influence school life in the eastern German states.

West Germany

After World War II, the Allied powers (Soviet Union, France, United Kingdom, and the U.S.) ensured that Nazi ideology was eliminated from the curriculum. They installed educational systems in their respective occupation zones that reflected their own ideas. When West Germany gained partial independence in 1949, its new constitution (Grundgesetz) granted educational autonomy to the state (Länder) governments. This led to widely varying school systems, often making it difficult for children to continue schooling whilst moving between states.

Multi-state agreements ensure that basic requirements are universally met by all state school systems. Thus, all children are required to attend one type of school (five or six days a week) from the age of 6 to the age of 16. A pupil may change schools in the case of exceptionally good (or exceptionally poor) ability. Graduation certificates from one state are recognized by all the other states. Qualified teachers are able to apply for posts in any of the states.

Federal Republic of Germany

Since the 1990s, a few changes have been taking place in many schools:

- Introduction of bilingual education in some subjects

- Experimentation with different styles of teaching

- Equipping all schools with computers and Internet access

- Creation of local school philosophy and teaching goals (Schulprogramm), to be evaluated regularly

- Reduction of Gymnasium school years (Abitur after grade 12) and introduction of afternoon periods as in many other western countries (turned down in 2019)

In 2000 after much public debate about Germany's perceived low international ranking in Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), there has been a trend towards a less ideological discussion on how to develop schools. These are some of the new trends:

- Establishing federal standards on quality of teaching

- More practical orientation in teacher training

- Transfer of some responsibility from the Ministry of Education to local school

Further outcomes:

- Bilingual education now requires mandatory English lessons in Grundschule

- The educational act (Bildungspakt) in 2019 is designed to increase the use of the internet and computers in schools.

Overview

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (March 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In Germany, education is the responsibility of the states (Länder) and part of their constitutional sovereignty (Kulturhoheit der Länder). Teachers are employed by the Ministry of Education for the state and usually have a job for life after a certain period (verbeamtet). This practice depends on the state and is currently changing. A parents' council is elected to voice the parents' views to the school's administration. Each class elects one or two Klassensprecher (class presidents; if two are elected usually one is male and the other female), who meet several times a year as the Schülerrat (students' council).

A team of school presidents is also elected by the pupils each year, whose main purpose is organizing school parties, sports tournaments and the like for their fellow students. The local town is responsible for the school building and employs the janitorial and secretarial staff. For an average school of 600 – 800 students, there may be two janitors and one secretary. School administration is the responsibility of the teachers, who receive a reduction in their teaching hours if they participate.

Church and state are separated in Germany. Compulsory school prayers and compulsory attendance at religious services at state schools are against the constitution.

Literacy

Over 99% of Germans aged 15 and above are estimated to be able to read and write.

Preschool

German preschool is known as a Kindergarten (plural Kindergärten) or Kita, short for Kindertagesstätte (meaning "children's daycare center"). Children between the ages of 2 and 6 attend Kindergärten, which are not part of the school system. They are often run by city or town administrations, churches, or registered societies, many of which follow a certain educational approach as represented, e.g., by Montessori or Reggio Emilia or Berliner Bildungsprogramm. Forest kindergartens are well established. Attending a Kindergarten is neither mandatory nor free of charge, but can be partly or wholly funded, depending on the local authority and the income of the parents. All caretakers in Kita or Kindergarten must have a three-year qualified education, or be under special supervision during training.

Kindergärten can be open from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m. or longer and may also house a Kinderkrippe, meaning crèche, for children between the ages of eight weeks and three years, and possibly an afternoon Hort (often associated with a primary school) for school-age children aged 6 to 10 who spend the time after their lessons there. Alongside nurseries, there are day-care nurses (called Tagesmutter, plural Tagesmütter—the formal, gender-neutral form is Tagespflegeperson(en)) working independently from any pre-school institution in individual homes and looking after only three to five children typically up to three years of age. These nurses are supported and supervised by local authorities.

The term Vorschule, meaning 'pre-school', is used both for educational efforts in Kindergärten and for a mandatory class that is usually connected to a primary school. Both systems are handled differently in each German state. The Schulkindergarten is a type of Vorschule.

During the German Empire, children were able to pass directly into secondary education after attending a privately run, fee-based Vorschule which then was another sort of primary school. The Weimar Constitution banned these, feeling them to be an unjustified privilege, and the Basic Law still contains the constitutional rule (Art. 7 Sect. VI) that: Pre-schools shall remain abolished.

Homeschooling

Main article: Homeschooling international status and statistics § GermanyHomeschooling is – between Schulpflicht (compulsory schooling) beginning with elementary school to 18 years – illegal in Germany. The illegality has to do with the prioritization of children's rights over the rights of parents: children have the right to the company of other children and adults who are not their parents. For similar reasons, parents cannot opt their children out of sexual education classes because the state considers a child's right to information to be more important than a parent's desire to withhold it.

Primary education

Parents looking for a suitable school for their child have a wide choice of elementary schools:

- State school. State schools do not charge tuition fees. The majority of pupils attend state schools in their neighbourhood. Schools in affluent areas tend to be better than those in deprived areas. Once children reach school age, many middle-class and working-class families move away from deprived areas.

- or, alternatively

- Waldorf school (2,006 schools in 2007) (covers grades from 1–13)

- Montessori method school (272)

- Freie Alternativschule (free alternative school) (85)

- Protestant (63) or Catholic (114) parochial schools

The entry year can vary between 5 and 7, while stepping back or skipping a grade is also possible.

Secondary education

See also: Education in Berlin and Education in Hamburg| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (March 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

After children complete their primary education (at 10 years of age/grade 4, 12 year of age in Berlin and Brandenburg), there are four options for secondary schooling:

- Gymnasium (Germany) until grade 12 or 13 (with Abitur as exit exam, qualifying for university).

- Realschule until grade 10 or 11 (with Mittlere Reife (or Realschulabschluss) as exit exam); students can then attend Berufsfachschule (full-time vocational schools) or Fachoberschule for 2-3 years, which combines vocational school and an apprenticeship. In some regions there is Regionalschule, which is a combination of Realschule and Hauptschule. Pupils study for either 9 years, to obtain a qualification similar to the Hauptschulabschluss, or 10 years, to get the Mittlere Reife.

- Hauptschule until grade 9, with an exam called the Hauptschulabschluss, to conclude. Afterwards, students can attend vocational schools.

- Gesamtschule, which is a combination of the above, for 5-8 years, with a different qualification for different durations: 5 years for the Hauptschulabschluss; if a student opts for the longer 8 year program, they can take the gymnasium abitur exam, qualifying for university.

After passing through any of the above schools, pupils can start a career with an apprenticeship in a Berufsschule ( vocational school). And the passing system is different from other countries. German secondary schools follow points system (punkte). Berufsschule is normally attended twice a week during a two, three, or three-and-a-half-year apprenticeship; the other days are spent working at a company. This is intended to provide a knowledge of theory and practice. The company is obliged to accept the apprentice on its apprenticeship scheme. After this, the apprentice is registered on a list at the Industrie- und Handelskammer (IHK) (chamber of industry and commerce). During the apprenticeship, the apprentice is a part-time salaried employee of the company. After passing the Berufsschule and the exit exams of the IHK, a certificate is awarded and the young person is ready for a career up to a low management level. In some areas, the schemes teach certain skills that are a legal requirement (special positions in a bank, legal assistants).

Some special areas provide different paths. After attending any of the above schools and gaining a leaving certificate like Hauptschulabschluss, Mittlere Reife (or Realschulabschuss, from a Realschule) or Abitur from a Gymnasium or a Gesamtschule, school leavers can start a career with an apprenticeship at a Berufsschule ( vocational school). Here the student is registered with certain bodies, e.g. associations such as the German Bar Association (Deutsche Rechtsanwaltskammer, GBA) (board of directors). During the apprenticeship, the young person is a part-time salaried employee of the institution, bank, physician or attorney's office. After leaving the Berufsfachschule and passing the exit examinations set by the German Bar Association or other relevant associations, the apprentice receives a certificate and is ready for a career at all levels except in positions which require a specific higher degree, such as a doctorate. In some areas, the apprenticeship scheme teaches skills that are required by law, including certain positions in a bank or those as legal assistants. The 16 states have exclusive responsibility in the field of education and professional education. The federal parliament and the federal government can influence the educational system only by financial aid to the states. There are many different school systems, but in each state the starting point is always the Grundschule (elementary school) for a period of four years; or six years in the case of Berlin and Brandenburg.

| 1970 | 1982 | 1991 | 2000 | |

| Hauptschulabschluss | 87.7% | 79.3% | 66.5% | 54.9% |

| Realschulabschluss | 10.9% | 17.7% | 27% | 34.1% |

| Abitur | 1.4% | 3% | 6.5% | 11% |

Grades 5 and 6 form an orientation or testing phase (Orientierungs- or Erprobungsstufe) during which students, their parents and teachers decide which of the above-mentioned paths the students should follow. In all states except Berlin and Brandenburg, this orientation phase is embedded into the program of the secondary schools. The decision for a secondary school influences the student's future, but during this phase changes can be made more easily. In practice this rarely comes to bear because teachers are afraid of sending pupils to more academic schools whereas parents are afraid of sending their children to less academic schools. In Berlin and Brandenburg, the orientation is embedded into that of the elementary schools. Teachers give a so-called educational (path) recommendation (Bildungs(gang)empfehlung) based on scholastic achievements in the main subjects (mathematics, German, natural sciences, foreign language) and classroom behavior with details and legal implications differing from state to state: in some German states, those wishing to apply to a Gymnasium or Realschule require such a recommendation stating that the student is likely to make a successful transition to that type of school; in other cases anyone may apply. In Berlin 30% – 35% of Gymnasium places are allocated by lottery. A student's performance at primary school is immaterial. While the entry year is depending on the last year in the Grundschule stepping back or skipping a grade is possible between 7th and 10th grade and only stepping back between 5th and 6th grade (so called Erprobungsstufe, meaning testing grade) and 11th and 12th grade.

The eastern states Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia combine Hauptschule and Realschule into Sekundarschule, Mittelschule and Regelschule respectively. All German states have Gymnasium as one possibility for the more able children, and all states—except Saxony—have some Gesamtschulen, but in different forms. The states of Berlin and Hamburg have only two types of schools: comprehensive schools and Gymnasium.

Learning a foreign language is compulsory throughout Germany in secondary schools and English is one of the more popular choices. Students at certain Gymnasium are required to learn Latin as their first foreign language and choose a second foreign language. The list of available foreign languages as well as the hours of compulsory foreign language lessons differ from state to state, but the more common choices besides Latin are English, French, Spanish, and ancient Greek. Many schools also offer voluntary study groups for the purpose of learning other languages. At which stage students begin learning a foreign language differs from state to state and is tailored to the cultural and socio-economical dynamics of each state. In some states, foreign language education starts in Grundschule (primary school). For example, in North Rhine-Westphalia and Lower Saxony, English starts in the third year of elementary school. Baden-Württemberg starts with English or French in the first year. The Saarland, which borders France, begins with French in the third year of primary school and French is taught in high school as the main foreign language.

It may cause problems in terms of education for families that plan to move from one German state to another as there are partially completely different curricula for nearly every subject.

Realschule students gain the chance to take their Abitur at a Gymnasium with a good degree in the Realschulabschluss. Stepping up is always provided by the school system. Adults who did not achieve a Realschulabschluss or Abitur, or reached its equivalent, have the option of attending evening classes at an Abendgymnasium or Abendrealschule.

School organization

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (March 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

A few organizational central points are listed below. It should however be noted that due to the decentralized nature of the education system there are many more additional differences across the 16 states of Germany.

- Every state has its own school system.

- Each age group of students (born roughly in the same year) forms one or more grades or classes (Klassen) per school which remain the same for elementary school (years 1 to 4 or 6), orientation school (if there are orientation schools in the state), orientation phase (at Gymnasium years 5 to 6), and secondary school (years 5 or 7 to 10 in Realschulen and Hauptschulen; years 5 or 7 to 10 (differences between states) in Gymnasien) respectively. Changes are possible, though, when there is a choice of subjects, e.g. additional languages; Then classes will be split (and newly merged) either temporarily or permanently for this particular subject.

- Students usually sit at tables, not desks (usually two at one table), sometimes arranged in a semicircle or another geometric or functional shape. During exams in classrooms, the tables are sometimes arranged in columns with one pupil per table (if permitted by the room's capacities) to prevent cheating; at many schools, this is only the case for some exams in the two final years of school, i.e. some of the exams counting for the final grade on the high school diploma.

- There is usually no school uniform or dress code. Many private schools have a simplified dress code, for instance, such as "no shorts, no sandals, no clothes with holes". Some schools are testing school uniforms, but those are not as formal as seen in the UK. They mostly consist of a normal sweater/shirt and jeans of a certain color, sometimes with the school's symbol on it. It is however a common custom to design graduation class shirts in Gymnasium, Realschule and Hauptschule.

- School usually starts between 7.30 a.m. and 8:15 a.m. and can finish as early as 12; instruction in lower classes almost always ends before lunch. In higher grades, however, afternoon lessons are very common and periods may have longer gaps without teacher supervision between them. Usually, afternoon classes are not offered every day and/or continuously until early evening, leaving students with large parts of their afternoons free of school; some all-day schools (Ganztagsschulen), however, offer classes or mainly-supervised activities throughout the afternoons to offer supervision for the students rather than increasing teaching hours. Afternoon lessons can continue until 6 o'clock.

- Depending on school, there are breaks of 5 to 20 minutes after each period. There is no lunch break as school usually finishes before 1:30 for junior school. However, at schools with Nachmittagsunterricht (afternoon classes) ending after 1:30, there may be a lunch break of 45 to 90 minutes, though many schools lack any special break in general. Some schools have regular breaks of 5 minutes between every lesson and have additional 10 or 15-minute breaks after the second and fourth lesson.

- In German state schools lessons have a length of exactly 45 minutes. Each subject is usually taught for two to three periods every week (main subjects like mathematics, German or foreign languages are taught for four to six periods) and usually no more than two periods consecutively. The beginning of every period and, usually, break is announced with an audible signal such as a bell.

- Exams (which are always supervised) are usually essay-based, rather than multiple choice. As of 11th grade, exams usually consist of no more than three separate exercises. While most exams in the first grades of secondary schools usually span no more than 90 minutes, exams in 10th to 12th grade may span four periods or more (without breaks).

- At every type of school, pupils study one foreign language (in most cases English) for at least five years. The study of languages is, however, far more rigorous and literature-oriented in Gymnasium. In Gymnasium, students can choose from a wider range of languages (mostly English, French, Russian—mostly in east German Bundesländer—or Latin) as the first language in 5th grade, and a second mandatory language in 7th grade. Some types of Gymnasium also require an additional third language (such as Spanish, Italian, Russian, Latin or Ancient Greek) or an alternative subject (usually based on one or two other subjects, e.g. British politics (English and politics), dietetics (biology) or media studies (arts and German) in 9th or 11th grade. Gymnasiums normally offer further subjects starting at 11th grade, with some schools offering a fourth foreign language.

- A number of schools once had a Raucherecke (smokers' corner), a small area of the schoolyard where students over the age of eighteen are permitted to smoke on their breaks. Those special areas were banned in the states of Berlin, Hessen, and Hamburg, Brandenburg at the beginning of the 2005–06 school year. (Bavaria, Schleswig-Holstein, Lower Saxony 2006–07)). Schools in these states prohibit smoking for students and teachers and offences at school will be punished. All other states in Germany introduced similar laws in the aftermath of EU regulations on smoking.

- As state schools are public, smoking is universally prohibited inside the buildings. Smoking teachers are generally asked not to smoke while at or near school.

- Students over 14 years are permitted to leave the school compound during breaks at some schools. Teachers or school personnel tend to prevent younger students from leaving early and strangers from entering the compound without permission.

- Tidying up the classroom and schoolyard is often the task of the students themselves. Unless a group of volunteering students, individuals are being picked sequentially.

- Many schools have AGs or Arbeitsgemeinschaften (clubs) for afternoon activities such as sports, music or acting, but participation is not necessarily common. Some schools also have student volunteer mediators trained to resolve conflicts between their classmates or younger students.

- Few schools have actual sports teams that compete with other schools. Even if the school has a sports team, students are not necessarily very aware of it.

- While student newspapers used to be very common until the late 20th century, with new issues often produced every couple of months, many of them are now very short-lived, usually vanishing when the class graduates. Student newspapers are often financed mostly by advertisements.

- Schools don't often have their own radio stations or TV channels; larger universities often have a local student-run radio station.

- Although most German schools and state universities do not have classrooms equipped with a computer for each student, schools usually have at least one or two computer rooms and most universities offer a limited number of rooms with computers on every desk. State school computers are usually maintained by the same exclusive contractor in the entire city and updated slowly. Internet access is often provided by phone companies free of charge.

- At the end of their schooling, students usually undergo a cumulative written and oral examination (Abitur in Gymnasien or Abschlussprüfung in Realschulen and Hauptschulen). Students leaving Gymnasium after 9th grade have the Hauptschule leaving examination and after 10th grade they have the Mittlere Reife (leaving examination of the Realschule, also called Mittlerer Schulabschluss).

- After 10th grade Gymnasium students may leave school for at least one year of job education if they do not wish to continue. Realschule and Hauptschule students who have passed their Abschlussprüfung may decide to continue schooling at a Gymnasium, but are sometimes required to take additional courses to catch up.

- Corporal punishment was banned in 1949 in East Germany and in 1973 in West Germany.

- Fourth grade (or sixth, depending on the state) is often quite stressful for students of lower performance and their families. Many feel tremendous pressure when trying to achieve placement in Gymnasium, or at least when attempting to avoid placement in Hauptschule. Germany is unique compared to other western countries in its early segregation of students based on academic achievement.

School year

The school year starts after the summer break (different from state to state, usually end/mid of August) and is divided into two terms. There are typically 12 weeks of holidays in addition to public holidays. Exact dates differ between states, but there are generally six weeks of summer and two weeks of Christmas holiday. The other holiday periods occur in spring (during the period around Easter Sunday) and autumn (during the former harvest, where farmers used to need their children for field work). In some states schools can also schedule two or three special days off per term.

Timetables

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (March 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Students have about 30–40 periods of 45 minutes each per week (depending on year and state), but secondary schools in particular have switched to 90-minute lessons (Block) which count as two 'traditional' lessons. To manage classes that are taught three or five lessons per week there are two common ways. At some schools with 90-minute periods there is still one 45-minute lesson each day, mostly between the first two blocks; at other schools those subjects are taught in weekly or term rotations. There are about 12 compulsory subjects: up to three foreign languages (the first is often begun in primary school, the second one in 6th or 7th grade, and the third somewhere between 7th and 11th grade), physics, biology, chemistry, civics/social/political studies, history, geography (starting between 5th and 7th grade), mathematics, music, visual arts, German, physical education, and religious education/ethics (to be taken from primary school on). The range of offered afternoon activities is different from school to school; however, most German schools offer choirs or orchestras, and sometimes sports, theater or languages. Many of these are offered as semi-scholastic AGs (Arbeitsgemeinschaften—literally "working groups"), which are noted in students' reports but not officially graded. Other common extracurricular activities are organized as private clubs, which are very popular in Germany.

| Time | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 08.00–08.45 | English | Physics | Biology | Physics | Greek |

| 08.45–09.30 | History | English | Chemistry | Mathematics | Chemistry |

| 09.30–09.40 | Break | ||||

| 09.40–10.25 | Latin | Greek | Mathematics | Latin | Economics |

| 10.25–11.10 | German | Geography | Religious studies | Greek | German |

| 11.10–11.30 | Break | ||||

| 11.30–12.15 | Music | Mathematics | Geography | German | Biology |

| 12.15–13.00 | Religious studies | Civic education | Economics | English | Latin |

| 13.00–14.00 | Break | ||||

| 14.00–14.45 | Arts | Intensive course | |||

| 14.45–15.30 | Intensive course | Greek | |||

| 15.30–16.15 | PE | ||||

| 16.15–17.00 | PE | ||||

There are three blocks of lessons, with each lesson taking 45 minutes. After each block, there is a break of 15–20 minutes, including after the sixth lesson (the number of lessons changes from year to year, so it is possible that one could be in school until 16.00). Nebenfächer (minor fields of study) are taught twice a week; Hauptfächer (major subjects) are taught three times.

In grades 11–13, 11–12, or 12–13 (depending on the school system), each student majors in two or three subjects (Leistungskurse), in which there are usually five lessons per week. The other subjects (Grundkurse) are usually taught three periods per week.

| Time | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 08.00–08.45 | English | Religious studies | French | Physics | German |

| 08.50–09.35 | English | Religious studies | French | Physics | German |

| 09.55–10.40 | German | Geography/Social Studies (taught in English) |

Mathematics | Geography/Social Studies (taught in English) |

Mathematics |

| 10.45–11.30 | German | Geography/Social Studies (taught in English) |

Mathematics | Geography/Social Studies (taught in English) |

Mathematics |

| 11.50–12.35 | Physics | Politics-Economy | History | English | French |

| 12.40–13.25 | Physics | Politics-Economy | History | English | French |

| 13.40–14.25 | Arts | "Seminarfach"+ | History | PE (different sports offered as courses) | |

| 14.30–15.15 | Arts | "Seminarfach"+ | History | PE (different sports offered as courses) |

+ Seminarfach is a compulsory class in which each student is prepared to turn in his/her own research paper at the end of the semester. The class is aimed at training students' scientific research skills that will later be necessary in university.

There are significant differences between the 16 states' alternatives to this basic template, such as Waldorfschulen or other private schools. Adults can also go back to evening school and take the Abitur exam.

Public and private schools

In 2006, six percent of German children attended private schools.

In Germany, Article 7, Paragraph 4 of the Grundgesetz, the constitution of Germany, guarantees the right to establish private schools. This article belongs to the first part of the German basic law, which defines civil and human rights. A right which is guaranteed in this part of the Grundgesetz can only be suspended in a state of emergency if the respective article specifically states this possibility. That is not the case with this article. It is also not possible to abolish these rights. This unusual protection of private schools was implemented to protect them from a second Gleichschaltung or similar event in the future.

Ersatzschulen are ordinary primary or secondary schools which are run by private individuals, private organizations or religious groups. These schools offer the same types of diplomas as in public schools. However, Ersatzschulen, like their state-run counterparts, are subjected to basic government standards, such as minimum required qualifications for teachers and pay grades. An Ersatzschule must have at least the same academic standards as those of a state school and Article 7, Paragraph 4 of the Grundgesetz forbids the segregation of pupils based on socioeconomic status (the so-called Sonderungsverbot). Therefore, most Ersatzschulen have very low tuition fees compared to those in most other Western European countries; scholarships are also often available. However, it is not possible to finance these schools with such low tuition fees: accordingly all German Ersatzschulen are subsidised with public funds.

Some students attend private schools through welfare subsidies. This is often the case if a student is considered to be a child at risk, such as students who have learning disabilities, special needs or come from dysfunctional home environments.

After factoring in parents' socioeconomic status, children who attend private schools are not as able as those at state schools. At the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) for example, after considering socioeconomic class, students at private schools underperformed those at state schools. One has, however, to be careful interpreting that data: it may be that such students do not underperform because they attend a private school, but that they attend a private school because they underperform. Some private Realschulen and Gymnasien have lower entry requirements than public Realschulen and Gymnasien.

Special schools

Most German children with disabilities attend a school called Förderschule or Sonderschule (special school) that serves only such children. There are several types of special schools in Germany such as:

- Sonderschule für Lernbehinderte—a special school serving children who have learning difficulties

- Schule mit dem Förderschwerpunkt Geistige Entwicklung—a special school serving children who have very severe learning difficulties

- Förderschule Schwerpunkt emotionale und soziale Entwicklung—a special school serving children who have special emotional needs

Only one in 21 German children attends such a special school. Teachers at those schools are qualified professionals who have specialized in special-needs education while at university. Special schools often have a very favourable student-teacher ratio and facilities compared with other schools. Special schools have been criticized. It is argued that special education separates and discriminates against those who are disabled or different. Some special-needs children do not attend special schools, but are mainstreamed into a Hauptschule or Gesamtschule (comprehensive school) and/or, in rare cases, into a Realschule or even a Gymnasium.

Elite schools

There are very few specialist schools for gifted children. As German schools do not IQ-test children, most intellectually gifted children remain unaware that they fall into this category. The German psychologist, Detlef H. Rost, carried out a pioneer long-term study on gifted children called the Marburger Hochbegabtenprojekt. In 1987/1988 he tested 7000 third graders on a test based on the German version of the Cattell Culture Fair III test. Those who scored at least two standard deviations above the mean were categorised as gifted. A total of 151 gifted subjects participated in the study alongside 136 controls. All participants in the study were tested blind with the result that they did not discover whether they were gifted or not. The study revealed that the gifted children did very well in school. The vast majority later attended a Gymnasium and achieved good grades. However, 15 percent, were classified as underachievers because they attended a Realschule (two cases) or a Hauptschule (one case), had repeated a grade (four cases) or had grades that put them in the lower half of their class (the rest of cases). The report also concluded that most gifted persons had high self-esteem and good psychological health. Rost said that he was not in favour of special schools for the gifted. Gifted children seemed to be served well by Germany's existing school system.

International schools

As of January 2015 the International Schools Consultancy (ISC) listed Germany as having 164 international schools. ISC defines an 'international school' in the following terms: "ISC includes an international school if the school delivers a curriculum to any combination of pre-school, primary or secondary students, wholly or partly in English outside an English-speaking country, or if a school in a country where English is one of the official languages, offers an English-medium curriculum other than the country's national curriculum and is international in its orientation." This definition is used by publications including The Economist. In 1971 the first International Baccalaureate World School was authorized in Germany. Today 70 schools offer one or more of the IB programmes including two who offer the new IB Career-related Programme.

International comparisons

The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), coordinated by the OECD, assesses the skills of 15-year-olds in OECD countries and a number of partner countries. The assessment in the year 2000 demonstrated serious weaknesses in German pupils' performance. In the test of 41 countries, Germany ranked 21st in reading and 20th in both mathematics and the natural sciences, prompting calls for reform. Major newspapers ran special sections on the PISA results, which were also discussed extensively on radio and television. In response, Germany's states formulated a number of specific initiatives addressing the perceived problems behind Germany's poor performance.

By 2006, German schoolchildren had improved their position compared to previous years, being ranked (statistically) significantly above average (rank 13) in science skills and statistically not significantly above or below average in mathematical skills (rank 20) and reading skills (rank 18). In 2012, Germany achieved above average results in all three areas of reading, mathematics, and natural sciences. This declined in the 2018 report.

The PISA Examination also found big differences in achievement between students attending different types of German schools. The socio-economic gradient was very high in Germany, the students' performance there being more dependent on socio-economic factors than in most other countries.

| Performance on PISA 2003 (points earned) by school attended and social class | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| type school | social class "very low" | social class "low" | social class "high" | social class "very high" |

| Hauptschule | 400 | 429 | 436 | 450 |

| Gesamtschule | 438 | 469 | 489 | 515 |

| Realschule | 482 | 504 | 528 | 526 |

| Gymnasium | 578 | 581 | 587 | 602 |

| PISA 2003 – Der Bildungsstand der Jugendlichen in Deutschland – Ergebnisse des 2. internationalen Vergleiches. | ||||

Some German teachers' representatives and a number of scientists disputed the PISA findings. They claimed, amongst other things, that the questions had been ill-translated, that the samples drawn in some countries were not representative, that German students (most of whom had never done a multiple choice tests in their lives before) were disadvantaged by the multiple choice questions, that the PISA questions had no curricular validity and that PISA was "in fact an IQ-test", which according to them showed that dysgenic fertility was taking place in Germany. Additionally, the OECD was criticized for following its own agenda of a strictly economically utilitarian education policy—as opposed to humanist education policy following the German ideal of Bildung—and for trying to establish an educational testing industry without democratic legitimation.

Apprenticeship

Germany has high standards for the education of craftspeople. Historically very few people attended college. In the 1950s for example, 80 percent had only Volksschule ("primary school") education of 6 or 7 years. Only 5 percent of youths entered college at this time and still fewer graduated. In the 1960s, six percent of youths entered college. In 1961 there were still 8,000 cities in which no children received secondary education. However, this does not mean that Germany was a country of uneducated people. In fact, many of those who did not receive secondary education were highly skilled craftspeople and members of the upper middle class. Even though more people attend college today, a craftsperson is still highly valued in German society.

Historically (prior to the 20th century) the relationship between a master craftsman and his apprentice was paternalistic. Apprentices were often very young when entrusted to a master craftsman by their parents. It was seen as the master's responsibility not only to teach the craft, but also to instill the virtues of a good craftsman. He was supposed to teach honour, loyalty, fair-mindedness, courtesy and compassion for the poor. He was also supposed to offer spiritual guidance, to ensure his apprentices fulfilled their religious duties and to teach them to "honour the Lord" (Jesus Christ) with their lives. The master craftsman who failed to do this would lose his reputation and would accordingly be dishonoured – a very bad fate in those days. The apprenticeship ended with the so-called Freisprechung (exculpation). The master announced in front of the trade heading that the apprentice had been virtuous and God-loving. The young person now had the right to call himself a Geselle (journeyman). He had two options: either to work for a master or to become a master himself. Working for another master had several disadvantages. One was that, in many cases, the journeyman who was not a master was not allowed to marry and found a family. Because the church disapproved of sex outside of marriage, he was obliged to become a master if he did not want to spend his life celibate. Accordingly, many of the so-called Geselle decided to go on a journey in order to become a master. This was called Waltz or Journeyman years.

In those days, the crafts were called the "virtuous crafts" and the virtuousness of the craftspersons was greatly respected. For example, according to one source, a person should be greeted from "the bricklayer craftspersons in the town, who live in respectability, die in respectability, who strive for respectability and who apply respectability to their actions." In those days, the concept of the "virtuous crafts" stood in contrast to the concept of "academic freedom" as Brüdermann and Jost noticed.

Nowadays, the education of craftspersons has changed – in particular self-esteem and the concept of respectability. Yet even today, a craftsperson does sometimes refer to the "craftsperson's codex of virtues" and the crafts sometimes may be referred to as the "virtuous crafts" and a craftsperson who gives a blessing at a roofing ceremony may, in many cases, remind of the "virtues of the crafts I am part of". Certain virtues are also ascribed to certain crafts. For example, a person might be called "always on time like a bricklayer" to describe punctuality. On the other hand, "virtue" and "respectability", which in the past had been the center of the life of any craftsperson became less and less important for such education. Today, a young person who wants to start an apprenticeship must first find an Ausbilder: this may be a master craftsperson, a master in the industrial sector (Industriemeister) or someone else with proof of suitable qualifications in the training of apprentices. The Ausbilder must also provide proof of no criminal record and proof of respectability. The Ausbilder has to be at least 24 years of age. The Ausbilder has several duties, such as teaching the craft and the techniques, and instilling character and social skills. In some cases, the Ausbilder must also provide board and lodging. Agreement is reached on these points before the apprenticeship begins. The apprentice will also receive payment for his work. According to §17 Berufsbildungsgesetz, a first year apprentice will be paid less than someone who has been an apprentice for longer. An Ausbilder who provides board and lodging may set this off against the payment made. In the past, many of those who applied for an apprenticeship had only primary school education. Nowadays, only those with secondary school education apply for apprenticeships because secondary school attendance has become compulsory. In some trades, it has even become difficult for those holding the Hauptschulabschluss to find an apprenticeship because more and more pupils leave school with the Realschulabschluss or Abitur. The apprenticeship takes three years. During that time, the apprentice is trained by the Ausbilder and also attends a vocational school. This is called the German model or dual education system (Duale Ausbildung).

Tertiary education

See also: Academic ranks in Germany and List of universities in Germany

Germany's universities are recognised internationally; in the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) for 2008, six of the top 100 universities in the world are in Germany, and 18 of the top 200. Germany ranks third in the QS World University Rankings 2011.

Most German universities are public institutions, charging fees of only around €60–500 per semester for each student, usually to cover expenses associated with the university cafeterias and (usually mandatory) public transport tickets. Thus, academic education is open to most citizens and studying is very common in Germany. The dual education system combines both practical and theoretical education but does not lead to academic degrees. It is more popular in Germany than anywhere else in the world and is a role model for other countries.

The oldest universities of Germany are also among the oldest and best regarded in the world, with Heidelberg University being the oldest (established in 1386 and in continuous operation since then). It is followed by Cologne University (1388), Leipzig University (1409), Rostock University (1419), Greifswald University (1456), Freiburg University (1457), LMU Munich (1472) and the University of Tübingen (1477).

While German universities have a strong focus on research, a large part of it is also done outside of universities in independent institutes that are embedded in academic clusters, such as within the Max Planck, Fraunhofer, Leibniz and Helmholtz institutes. This German peculiarity of "outsourcing" research leads to a competition for funds between universities and research institutes and may negatively affect academic rankings.

Figures for Germany are roughly:

- 1,000,000 new students at all schools put together for one year

- 400,000 Abitur graduations

- 30,000 doctoral dissertations per year

- 1000 habilitations per year (the traditional way to qualify as a professor, but typically postdoc or junior professorship is the preferred career path nowadays, which are not accounted for in this number)

Types of universities

The German tertiary education system distinguishes between two types of institutions: The term Universität (university) is reserved for institutions which have the right to confer doctorates. Other degree-awarding higher education institutions may use the more generic term Hochschule.

In addition, non-university institutions of tertiary level exist in the German education system. The admission requirement is usually a previous education including work experience. As an example, Fachschulen for technological subjects can be cited, which are completed with a state examination (EQF level 6).

Universitäten

Only Universitäten have the right to confer doctorates and habilitations. Some universities use the term research university in international usage to emphasize their strength in research activity in addition to teaching, particularly to differentiate themselves from Fachhochschulen. A university covering the full range of scientific disciplines in contrast to more specialized universities might refer to itself as Volluniversität. Specialized universities which have the formal status of Universität include Technische Universitäten, Pädagogische Hochschulen (Universities of Education), Kunsthochschulen (Universities of Arts) and Musikhochschulen (Universities of Music). The excellence initiative has awarded eleven universities with the title University of Excellence. Professors at regular universities were traditionally required to have a doctorate as well as a habilitation. Since 2002, the junior professorship was introduced to offer a more direct path to employment as a professor for outstanding doctoral degree.

Fachhochschulen (Universities of Applied Sciences)

Main article: FachhochschuleThere is another type of university in Germany: the Fachhochschulen (Universities of Applied Sciences), which offer mostly the same degrees as Universitäten, but often concentrate on applied science (as the English name suggests) and usually have no power to award PhD-level degrees, at least not in their own right. Fachhochschulen have a more practical profile with a focus on employability. In research, they are rather geared to applied research instead of fundamental research. At a traditional university, it is important to study "why" a method is scientifically right; however, this is less important at Universities of Applied Sciences. Here the emphasis is placed on what systems and methods exist, where they come from, what their advantages and disadvantages are, how to use them in practice, when they should be used, and when not.

For professors at a Fachhochschule, at least three years of work experience are required for appointment while a habilitation is not expected. This is unlike their counterparts at traditional universities, where an academic career with research experience is necessary.

Prior to the Bologna Process, Fachhochschule graduates received a Diplom. To differentiate it from the Diplom which was conferred by Universitäten, the title is indicated starting with "Dipl." (Diplom) and ending with (FH), e.g., Dipl. Ing. (FH) Max Mustermann for a graduate engineer from a Fachhochschule. The FH Diploma is roughly equivalent to a bachelor's degree. An FH Diploma does not qualify the holder for a doctoral program directly, but in practice universities admit the best FH graduates on an individual basis after an additional entrance exam or participation in theoretical classes.

Admission

University entrance qualification

Students wishing to attend a German Universität must, as a rule, hold the Abitur or a subject-restricted qualification for university entrance (Fachgebundene Hochschulreife). For Fachhochschulen, the Abitur, the Fachgebundene Hochschulreife certification or the Fachhochschulreife certification (general or subject-restricted) is required.

Lacking these school leaving certifications, in some states potential students can qualify for university entrance if they present additional formal proof that they will be able to keep up with their fellow students. This may take the form of a test of cognitive functioning or passing the Begabtenprüfung ("aptitude test", consisting of a written and oral exam). In some cases, students who do not hold the Abitur may enter university even if they do not pass the aptitude or cognitive functioning tests if they 1) have received previous vocational training, and 2) have worked at least three years and passed the Eingangsprüfung (entrance exam). Such is the case, for example, in Hamburg.

While there are numerous ways to achieve entrance qualification to German universities, the most traditional route has always been graduation from a Gymnasium with the Abitur; however this has become less common over time. As of 2008, less than half of university freshmen in some German states had graduated from a Gymnasium. Even in Bavaria (a state with a policy of strengthening the Gymnasium) only 56 percent of freshmen had graduated from a Gymnasium. The rest were awarded the Abitur from another type of school or did not hold the Abitur certification at all.

High school diplomas received from countries outside of Germany are, in many cases, not considered equivalent to the Abitur, but rather to a Realschulabschluss and therefore do not qualify the bearer for admission to a German university. However, it is still possible for such applicants to be admitted to a German university if they fulfill additional formal criteria, such as a particular grade point average or points on a standardized admissions test. These criteria depend on the school leaving certificate of the potential student and are agreed upon by the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs. For example, holders of the US high school diploma with a combined math and verbal score of 1300 on the SAT or 29 on the ACT may qualify for university admission.

Foreign students lacking the entrance qualification can acquire a degree at a Studienkolleg, which is often recognized as an equivalent to the Abitur. The one-year course covers similar topics as the Abitur and ensures sufficient language skills to take up studies at a German university.

Admissions procedure

The process of application depends on the degree program applied for, the applicant's origin and the university entrance qualification. Generally, all programs of study follow one of three admissions procedures.

- Free admissions: Every applicant who fulfills the university entrance qualification will be admitted. This is usually practiced in subjects in which many students quit their studies, e.g., mathematics, physics or engineering. Sometimes, the number of students who fail a course can be as high as 94 percent in these programs.

- Local admission restrictions: For degree programs where only a limited number of places are available (numerus clausus, often abbreviated NC), criteria by which applications will be evaluated differ from university to university and from program to program. Commonly used criteria include the final grade of the university entrance qualification (which takes into account the grades of the final exams as well as course grades), a weighted grade point average which increases the weight of relevant school subjects, interviews, motivational letters, letters of recommendation by previous professors, essays, relevant practical experience, and subject-specific entrance exams. Such restrictions are increasingly common at German universities.

- Nationwide admission restrictions: In the subjects medicine, dentistry, veterinary medicine, and pharmacy, a nationwide numerus clausus is in place. In these subjects, applications of Germans and foreigners who are legally treated like Germans (e.g., EU citizens) are handled centrally for all universities by a public trust (Stiftung für Hochschulzulassung). The following quotas are applied in this procedure:

- 20 percent of available admission slots are admitted by the final grade of the university entrance qualification

- 20 percent of slots are granted to students who have the highest number of so-called waiting semesters in which they were not enrolled at university

- 60 percent of slots are awarded by criteria at the university's discretion. Criteria universities commonly apply are: 1) final grade of the university entrance qualification (used most often), 2) interviews, 3) essays or motivational letters, and 4) entrance exams.

- some additional slots are reserved for special cases and do not count into the previous three quotas: For example, up to 2 percent of slots can be so called hardship cases (Härtefälle), which are granted preferential admission. An applicant may be counted as a hardship case only if there are exceptional circumstances making it impossible for the applicant to wait even a single semester for a place at university, e.g., because of a progressing disease.

According to German law, universities are not permitted to discriminate against or grant preferential treatment to persons on basis of race, ethnic group, gender, social class, religion or political opinion.

Tuition fees

Public universities in Germany are funded by the federal states and do not charge tuition fees. However, all enrolled students do have to pay a semester fee (Semesterbeitrag). This fee consists of an administrative fee for the university (only in some of the states), a fee for Studentenwerk, which is a statutory student affairs organization, a fee for the university's AStA (Allgemeiner Studentenausschuss, students' government) and Studentenschaft (students' union), at many universities a fee for public transportation, and possibly more fees as decided by the university's students' parliament (e.g., for a cooperation with a local theater granting free entry for students). Summed up, the semester fee usually ranges between €150 and €350.

In 2005, the German Federal Constitutional Court ruled that a federal law prohibiting tuition fees was unconstitutional, on the grounds that education is the sole responsibility of the states. Following this ruling, seven federal states introduced tuition fees of €500 per semester in 2006 and 2007. Due to massive student protests and a citizens' initiative which collected 70,000 signatures against tuition fees, the government of Hesse was the first to reverse course before the state election in 2008; other state governments soon followed. Several parties which spoke out for tuition fees lost state elections. Bavaria in 2013 and Lower Saxony in 2014 were the last states to abolish tuition fees.

Since 1998, all German states had introduced tuition fees for long-time students (Langzeitstudiengebühren) of €500 up to €900 per semester. These fees are required for students who study substantially longer than the standard period of study (Regelstudienzeit), which is a defined number of semesters for each degree program. Even after the abolition of general tuition fees, tuition fees for long-time students remain in six states. Additionally, universities may charge tuition fees for so called non-consecutive master's degree programs, which do not build directly on a bachelor's degree, such as a Master of Business Administration.

With much controversy, the state of Baden-Württemberg has reintroduced tuition fees at public universities starting in 2017. From autumn 2017, students who are not citizens of an EU/EEA member state are expected to pay €1,500 per semester. Students who enroll for their second degree in Germany are expected to pay €650 per semester regardless of their country of origin. Although heavily criticised in Germany, the amount is considered below average in comparison with other European countries.

There are university-sponsored scholarships in Germany and a number of private and public institutions award scholarships—usually to cover living costs and books. There is a state-funded study loan programme, called BAföG (Bundesausbildungsförderungsgesetz, "Federal Education Aid Act"). It ensures that less wealthy students can receive up to €735 per month for the standard period of study if they or their parents cannot afford all of the costs involved with studying. Furthermore, students need to have a prospect of remaining in Germany to be eligible; this includes German and EU citizens, but often also long-term residents of other countries. Part (typically half) of this money is an interest-free loan that is later repaid, with the other half considered a free grant, and the amount to be repaid is capped at €10,000. Currently, around a quarter of all students in Germany receive financial support via BAföG.

For international students there are different approaches to get a full scholarship or a funding of their studies. To be able to get a scholarship a successful application is mandatory. It can be submitted upon arrival in Germany as well as after arrival. But due to the fact that many scholarships are only available to students who are already studying, the chances of an acceptance are limited for applicants from abroad. Therefore, many foreign students have to work to finance their studies.

Students

Since the end of World War II, the number of young people entering a university has more than tripled in Germany, but university attendance is still lower than that of many other European nations. This can be explained with the dual education system with its strong emphasis on apprenticeships and vocational schools. Many jobs which do require an academic degree in other countries (such as nursing) require completed vocational training instead in Germany.

The rate of university graduates varies by federal state. The number is the highest in Berlin and the lowest in Schleswig-Holstein. Similarly, the ratio of school graduates with university entrance qualification varies by state between 38% and 64%.

The organizational structure of German universities goes back to the university model introduced by Wilhelm von Humboldt in the early 19th century, which identifies the unity of teaching and research as well as academic freedom as ideals. Colleges elsewhere had previously dedicated themselves to religion and classic literature, and Germany's shift to a research-based model was an institutional innovation. This model lead to the foundation of Humboldt University of Berlin and influenced the higher education systems of numerous countries. Some critics argue that nowadays German universities have a rather unbalanced focus, more on education and less on research.

At German universities, students enroll for a specific program of study (Studiengang). During their studies, students can usually choose freely from all courses offered at the university. However, all bachelor's degree programs require a number of particular compulsory courses and all degree programs require a minimum number of credits that must be earned in the core field of the program of study. It is not uncommon to spend longer than the regular period of study (Regelstudienzeit) at university. There are no fixed classes of students who study and graduate together. Students can change universities according to their interests and the strengths of each university. Sometimes students attend multiple different universities over the course of their studies. This mobility means that at German universities there is a freedom and individuality unknown in the US, the UK, or France. Professors also choose their subjects for research and teaching freely. This academic freedom is laid down in the German constitution.

Since German universities do not offer accommodation or meals, students are expected to organize and pay for board and lodging themselves. Inexpensive places in dormitories are available from Studentenwerk, a statutory non-profit organization for student affairs. However, there are only enough places for a fraction of students. Studentenwerk also runs canteens and cafés on campus, which are similarly affordable. Other common housing options include renting a private room or apartment as well as living together with one or more roommates to form a Wohngemeinschaft (often abbreviated WG). Furthermore, many university students continue to live with their parents. One third to one half of the students works to make a little extra money, often resulting in a longer stay at university.

Degrees

Further information: Academic degree § GermanyRecently, the implementation of the Bologna Declaration introduced bachelor's and master's degrees as well as ECTS credits to the German higher education system. Previously, universities conferred Diplom and Magister degrees depending on the field of study, which usually took 4–6 years. These were the only degrees below the doctorate. In the majority of subjects, students can only study for bachelor's and master's degrees, as Diplom or Magister courses do not accept new enrollments. However, a few Diplom courses still prevail. The standard period of study is usually three years (six semesters, with 180 ECTS points) for bachelor's degrees and two years (four semesters, 120 ECTS) for master's degrees. The following Bologna degrees are common in Germany:

- Bachelor of Arts (B.A.); Master of Arts (M.A.)

- Bachelor of Science (BSc); Master of Science (MSc)

- Bachelor of Engineering (BEng); Master of Engineering (MEng)

- Bachelor of Fine Arts (B.F.A.); Master of Fine Arts (M.F.A.)

- Bachelor of Music (B.Mus.); Master of Music (M.Mus.)

In addition, there are courses leading to the Staatsexamen (state examination). These did usually not transition to bachelor's and master's degrees. For future doctors, dentists, veterinarians, pharmacists, and lawyers, the Staatsexamen is required to be allowed to work in their profession. For teachers, judges, and public prosecutors, it is the required degree for working in civil service. Students usually study at university for 4–8 years before they take the First Staatsexamen. Afterwards, they go on to work in their future jobs for one or two years (depending on subject and state), before they are able to take the Second Staatsexamen, which tests their practical abilities. While it is not an academic degree formally, the First Staatsexamen is equivalent to a master's degree and qualifies for doctoral studies. On request, some universities bestow an additional academic degree (e.g., Diplom-Jurist or Magister iuris) on students who have passed First Staatsexamen.

The highest German academic degree is the doctorate. Each doctoral degree has a particular designation in Latin (except for engineering, where the designation is in German), which signifies in which field the doctorate is conferred in. The doctorate is indicated before the name in abbreviated form, e.g., Dr. rer. nat. Max Mustermann (for a doctor in natural sciences). The prefix "Dr." is used for addressing, for example in formal letters. Outside of the academic context, however, the designation is usually dropped.

While it is not an academic degree formally, the Habilitation is a higher, post-doctoral academic qualification for teaching independently at universities. It is indicated by appending "habil." after the designation of the doctorate, e.g., Dr. rer. nat. habil. Max Mustermann. The holder of a Habilitation may work as Privatdozent.

Research

Scientific research in Germany is conducted by universities and research institutes. The raw output of scientific research from Germany consistently ranks among the world's best. The national academy of Germany is the Leopoldina Academy of Sciences. Additionally, the Union of the German Academies of Sciences and Humanities acts as an umbrella organization for eight local academies and acatech is the Academy of Science and Engineering.

Organizations funding research

- Alexander von Humboldt Foundation

- Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG)

- Federal Ministry for Economics and Technology (BMWi)

- German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), promoting international exchange of scientists and students

National libraries

- German National Library of Economics (ZWB)

- German National Library of Medicine (ZB MED)

- German National Library of Science and Technology (TIB)

Research institutes

- Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres, an association of advanced research centers in science, technology, biology and medicine

- Max Planck Society, focusing on fundamental research

- Fraunhofer Society, focusing on applied research and mission oriented research

- Leibniz Association, addressing research issues of particular interest to the society

Prizes

Every year, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft awards ten outstanding scientists working at German research institutions with the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize, Germany's most important research prize. With a maximum of €2.5 million per award it is one of the highest endowed research prizes in the world. Additionally, numerous foundations and non-profit organizations award further prizes, medals and scholarships.

Determinants of academic attainment

50 years ago the person least likely to attend a Gymnasium was a "Catholic working-class girl from the rural parts of Germany". Nowadays however the person least likely to attend a Gymnasium is a "minority youngster from the ghetto", who is "the son of immigrants"

The influence of social class on educational achievement is much greater in western Germany than it is in eastern Germany (former GDR). An analysis of PISA data on Gymnasium pupils for the year 2000 showed that, while in western Germany the child of an academic was 7.26 times as likely as that of a skilled worker to attend, in eastern Germany a child from an academic family was only 2.78 times as likely as a working-class child to attend. The reasons for this were unclear. Some people believed that immigrants were responsible, because more uneducated immigrant families lived in western than in eastern Germany. This assumption however could not be confirmed. The difference between east and west was even stronger when only ethnic German children were studied.

Social class differences in educational achievement are much more marked in Germany's big cities than they are in the rural parts of Germany. In cities with more than 300,000 inhabitants, children of academics are 14.36 times as likely as children of skilled workers to attend Gymnasium.

Gender

Educational achievement varies more in German males than it does in German females: boys are more likely to attend special education schools but also more likely to be postgraduate students; 63% of pupils attending special education programs for the academically challenged are male. Males are less likely to meet the statewide performance targets, more likely to drop out of school and more likely to be classified emotionally disturbed. 86% of the pupils receiving special training because of emotional disturbance are male. Research shows a class-effect: native middle-class males perform as well as middle-class females in terms of educational achievement but lower-class males and immigrant males lag behind lower-class females and immigrant females. A lack of male role models contributes to a low academic achievement in the case of lower-class males . On the other hand, 58% of all postgraduate students and 84% of all German college professors were male in 2010.

Socioeconomic factors

See also: Poverty in Germany, German Gymnasium: Great Equaliser or Breeding Ground of Privilege?, and Academic achievement among different groups in GermanyChildren from poor immigrant or working-class families are less likely to succeed in school than children from middle- or upper-class backgrounds. This disadvantage for the financially challenged of Germany is greater than in any other industrialized nation. However, the true reasons stretch beyond economic ones. The poor also tend to be less educated. After allowing for parental education, money does not play a major role in children's academic outcomes.

Immigrant children and youths, mostly of lower-class background, are the fastest-growing segment of the German population. So their prospects bear heavily on the well-being of the country. More than 30% of Germans aged 15 years and younger have at least one parent born abroad. In the big cities, 60% of children aged 5 years and younger have at least one parent born abroad. Immigrant children academically underperform their peers. Immigrants have tended to be less educated than native Germans.