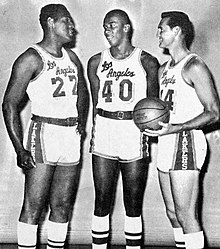

Baylor with the Los Angeles Lakers in 1969 Baylor with the Los Angeles Lakers in 1969 | |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Born | (1934-09-16)September 16, 1934 Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Died | March 22, 2021(2021-03-22) (aged 86) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Listed height | 6 ft 5 in (1.96 m) |

| Listed weight | 225 lb (102 kg) |

| Career information | |

| High school | |

| College |

|

| NBA draft | 1958: 1st round, 1st overall pick |

| Selected by the Minneapolis Lakers | |

| Playing career | 1958–1971 |

| Position | Small forward |

| Number | 22 |

| Coaching career | 1974–1979 |

| Career history | |

| As player: | |

| 1958–1971 | Minneapolis / Los Angeles Lakers |

| As coach: | |

| 1974–1976 | New Orleans Jazz (assistant) |

| 1974 | New Orleans Jazz (interim) |

| 1976–1979 | New Orleans Jazz |

| Career highlights and awards | |

As player:

As executive: | |

| Career statistics | |

| Points | 23,149 (27.4 ppg) |

| Rebounds | 11,463 (13.5 rpg) |

| Assists | 3,650 (4.3 apg) |

| Stats at NBA.com | |

| Stats at Basketball Reference | |

| Basketball Hall of Fame | |

| Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame | |

Elgin Gay Baylor (/ˈɛldʒɪn/ EL-jin; September 16, 1934 – March 22, 2021) was an American professional basketball player, coach, and executive. He played 14 seasons as a forward in the National Basketball Association (NBA) for the Minneapolis/Los Angeles Lakers. Baylor was a gifted shooter, a strong rebounder, and an accomplished passer, who was best known for his trademark hanging jump shot. The No. 1 draft pick in 1958, NBA Rookie of the Year in 1959, 11-time NBA All-Star, and a 10-time member of the All-NBA first team, Baylor is regarded as one of the game's all-time greatest players. In 1977, Baylor was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. In 1996, Baylor was named as one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History. In October 2021, Baylor was again honored as one of the league's greatest players of all time by being named to the NBA's 75th Anniversary Team. Baylor is the leader for most career rebounds in Lakers franchise history with 11,463.

Baylor spent 22 years as general manager of the Los Angeles Clippers, having managed the team for the majority of the Donald Sterling ownership period. He won the NBA Executive of the Year Award in 2006. Two years later, the Clippers relieved him of his executive duties shortly before the 2008–09 season began. In 1974, he volunteered to play a mixed doubles exhibition tennis match with Tracy Austin against Lawrence McCutcheon and Lea Antonopolis in Clarement, California, for a sold-out crowd.

His popularity led to appearances on the television series Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In in 1968; the Jackson 5's first TV special in 1971; a Buck Rogers in the 25th Century episode "Olympiad"; and an episode of The White Shadow titled "If Your Number's Up, Get Down".

Early life

Elgin "Rabbit" Baylor was born in Washington, D.C., on September 16, 1934, the son of Uzziel (Lewis) and John Wesley Baylor. He began playing basketball when he was 14. Although he grew up near a D.C. city recreation center, African Americans were banned from using the facilities, and Baylor had limited access to basketball courts growing up. He had two basketball-playing brothers, Sal and Kermit. After stints at Southwest Boys Club and Brown Jr. High, Baylor was a three-time All-City player in high school.

Baylor played his first two years of high school basketball at Phelps Vocational High School in the 1951 and 1952 seasons. At the time, public schools in Washington, D.C., were segregated, so he only played against other black high school teams. There, Baylor set his first area scoring record of 44 points, versus Cardozo H.S. During his two All-City years at Phelps, he averaged 18.5 and 27.6 points per season. He did not perform well academically and dropped out of school (1952–53) to work in a furniture store and play basketball in the local recreational leagues.

Baylor reappeared for the 1954 season as a senior playing for the recently opened all-black Spingarn High School. The 6 ft 5 in (1.96 m), 225 lb (102 kg) senior was named first-team Washington All-Metropolitan, and was the first African-American player named to that team. Baylor also won the SSA's Livingstone Trophy as the area's best basketball player for 1954. He finished with a 36.1 average for his eight Interhigh Division II league games.

On February 3, 1954, in a game against his old Phelps team, Baylor scored 31 in the first half. Playing with four fouls the entire second half, Baylor scored 32 more points to establish a new DC-area record with 63 points. This broke the point record of 52 that Western's Jim Wexler had set the year before when he broke Baylor's previous record of 44. However, because Wexler was white and Baylor was black, Baylor's record did not receive the same press coverage from the media, including the Washington Post, as Wexler's.

College career

Despite his success as a high school basketball player, no major college recruited Baylor because at the time, college scouts did not recruit at black high schools. While some colleges were willing to accept Baylor, he did not qualify academically. A friend of Baylor's who attended the College of Idaho helped arrange a football scholarship for Baylor for the 1954–55 academic year. Baylor never played football for the school, however; instead, he was accepted to the college's basketball team without having to try out. He outperformed the other players on the team that season, averaging over 31 points and 20 rebounds per game.

After the season, the College of Idaho dismissed its head basketball coach and restricted the scholarships. A Seattle car dealer interested Baylor in Seattle University, and Baylor sat out a year to play for Westside Ford, an Amateur Athletic Union team in Seattle, while establishing eligibility at Seattle. The Minneapolis Lakers drafted him in the 14th round of the 1956 NBA draft, but Baylor opted to stay in school instead.

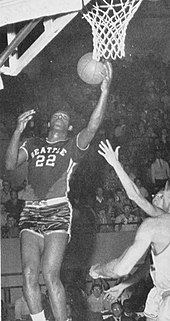

During the 1956–57 season, Baylor averaged 29.7 points per game and 20.3 rebounds per game for Seattle. The next season, Baylor averaged 32.5 points per game and led the Seattle University Chieftains (now known as the Redhawks) to the NCAA championship game, Seattle's only trip to the Final Four, falling to the Kentucky Wildcats. Following his junior season, Baylor was drafted again by the Minneapolis Lakers, with the No. 1 pick in the 1958 NBA draft, and this time he opted to leave school to join them for the 1958–59 NBA season.

Over three collegiate seasons, one at College of Idaho and two at Seattle, Baylor averaged 31.3 points per game and 19.5 rebounds per game. He led the NCAA in rebounds during the 1956–57 season.

Professional career

Minneapolis / Los Angeles Lakers (1958–1971)

Rookie of the Year (1958–1959)

The Minneapolis Lakers used the No. 1 overall pick in the 1958 NBA draft to select Baylor, then convinced him to skip his senior year at SU and instead join the pro ranks. The team had been unsuccessful since the retirement of its star center George Mikan in 1954. The year prior to Baylor's arrival, the team finished 19–53 – the worst record in the league – with a squad that was slow, bulky and aging. It had no permanent home arena to play in, was losing popularity, and in financial trouble. Owner Bob Short, who was ready to sell the team, believed Baylor's star athletic talents and all-around game could save the franchise. Short told the Los Angeles Times in a 1971 interview: "If he had turned me down then, I would have been out of business. The club would have gone bankrupt." Baylor signed with the Lakers for $20,000 per year (equivalent to $210,000 in 2023), a large sum in the NBA at the time. According to basketball historian James Fisher, by virtue of his exceptional skills and his central role in the team's business plan, Baylor became the NBA's first franchise player.

Baylor immediately exceeded expectations and ultimately saved the Lakers franchise. As a rookie in 1958–59, Baylor finished fourth in the league in scoring (24.9 points per game), third in rebounding (15.0 rebounds per game), and eighth in assists (4.1 assists per game). He scored 55 points in a single game, then the third-highest mark in league history behind Joe Fulks' 63 and Mikan's 61.

On January 16, 1959, Baylor refused to play in a road game in Charleston, West Virginia, after the hotel the team booked denied lodging to the team's three black players. When a teammate tried to convince Baylor to play in the game, Baylor said, "I'm a human being, I'm not an animal put in a cage and let out for the show."

Baylor won the NBA Rookie of the Year Award and led the Lakers to the NBA finals, where they lost to the Boston Celtics in the first four-game sweep in finals history, kicking off the greatest rivalry in NBA history.

Peak years (1959–1965)

In 1960, the Lakers moved from Minnesota to Los Angeles, drafted Jerry West to play point guard, and hired Fred Schaus who was also the coach during West's college career. The duo of Baylor and West, joined in 1968 by center Wilt Chamberlain, led the Lakers to success in the Western Division throughout the 1960s.

From the 1960–61 to the 1962–63 seasons, Baylor averaged 34.8, 38.3, and 34.0 points per game, respectively. On November 15 of the 1960–61 season, Baylor set an NBA scoring record when he scored 71 points in a victory against the New York Knicks, while also grabbing 25 rebounds. In doing so, Baylor became the first NBA player to score more than 70 points in a game, breaking his own NBA record of 64 points that he had set the previous November. Baylor held the record until 1962, when Chamberlain scored 100 points.

Baylor, a United States Army Reservist, was called to active duty during the 1961–62 season, and being stationed at Fort Lewis in Washington, he could play for the Lakers only when on a weekend pass. He was unable to practice with the team before or during the season, and had to fly coach across the country on weekends to join the team at whichever arena they were appearing. Despite playing only 48 games that season, he still managed to score over 1,800 points, averaging 38.3 points (the highest average in NBA history by any player other than Chamberlain), 18.6 rebounds, and 4.6 assists per game. Later that season, in a Game Five NBA Finals victory against the Boston Celtics, Baylor set the still-standing NBA record for points in an NBA Finals game with 61. Basketball historian James Fisher described Baylor's performance that season as: "Not bad for a part-time job." Baylor later said he "kind of enjoyed that season."

Knee injury and later seasons (1965–1971)

Baylor suffered a severe knee injury during the opening game of the 1965 Western Division playoffs, which required surgery and left him unable to play in the remainder of the playoffs. Although he scored more than 24 points in each of the next four seasons despite his injury, the limitations of knee surgery at the time and the lack of meaningful rehab left him with nagging knee problems, ultimately resulting in surgery on both knees, which impaired his playing ability for the rest of his career.

Baylor played just two games in 1970–71 before rupturing his Achilles tendon, and finally retired nine games into the subsequent 1971–72 season because of his nagging injuries. Baylor told the press that he could no longer play at the highest level of the sport and wanted to free up room on the Lakers' roster for other players.

In 14 seasons as the Lakers' forward, Baylor helped lead the team to the NBA Finals eight times, but the team lost each time. As a result of his retirement at the beginning of the season, Baylor missed two historic achievements: the Lakers' first game afterwards began an NBA record 33-game win streak, after which they won the 1972 championship.

Coaching career

In 1974, Baylor was hired to be an assistant coach and later the head coach for the New Orleans Jazz, but had a lackluster 86–135 record and was fired following the 1978–79 season, shortly before the team moved to Salt Lake City, Utah.

Executive career

In 1986, Baylor was hired by the Los Angeles Clippers as the team's vice president of basketball operations. He was selected as the NBA Executive of the Year in 2006. During his tenure, the Clippers managed only two winning seasons and amassed a win–loss record of 607–1153. They made the playoffs only four times, and won only one playoff series. He stayed in that capacity for 22 years until October 2008.

Later life and death

In 2009 Baylor filed an employment discrimination lawsuit against the Clippers, team owner Donald Sterling, team president Andy Roeser, and the NBA. He alleged that he was underpaid during his tenure with the team and then fired because of his age and race. Baylor later dropped the racial discrimination claims in the suit. In 2011, a jury decided in the Clippers' favor on Baylor's remaining claims, finding Baylor's termination was based on the team's poor performance. However, Baylor felt vindicated when Sterling was banned for life from the NBA in 2014 after recordings of him making racist comments were publicized by the press.

Baylor died in a Los Angeles hospital of natural causes on March 22, 2021, aged 86. He is interred in the Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Hollywood Hills. He was surrounded by his wife Elaine and their daughter Krystle; two children from a previous marriage, Alan and Alison; and a sister, Gladys.

Player profile

Baylor was known as an all-around player, excelling at defense, offense, rebounding, and passing. At 6'5", 225lbs, he was short for a forward even for the time period in which he played, but he had the strength to "muscle through" defenders, and the finesse and creativity to maneuver around them, including to rebound missed shots and score second chance points.

Baylor was known for his superior leaping abilities that allowed him to score by staying in the air longer than defenders; Bill Russell called him "the godfather of hang time." He invented "moves" to deceive defenders, involving changing hands or changing direction, even mid-air.

Baylor's offensive repertoire included a running bank shot and a left-handed hook shot, though he was right-handed. He had an on-court facial twitch that he used as a head fake. Baylor credited his success to a talent for jumping and the creativity to spontaneously react to the defense.

Legacy

Since the beginning of his NBA career, Baylor has been considered one of the best basketball players in the world, and his reputation as one of the greatest in history has endured. Before Baylor joined the NBA in 1958, the league's play was methodical but mechanical, dominated by set jump shots and running hook shots. Baylor introduced a creative and acrobatic playing style that would later be emulated by other NBA superstars such as Julius Erving and Michael Jordan. Bill Simmons wrote, "Along with Russell, Elgin turned a horizontal game into a vertical one." Baylor's skill was esteemed by his contemporaries: Oscar Robertson wrote Baylor "was the first and original high flier"; Bill Sharman said Baylor was "the greatest cornerman who ever played pro basketball"; Tom Heinsohn said, "Baylor as forward beats out Bird, Julius Erving and everybody else".

Baylor was the last of the great undersized forwards in a league where many guards are now his size or bigger. He finished his playing days with 23,149 points, 3,650 assists and 11,463 rebounds over 846 games. His signature running bank shot, which he was able to release quickly and effectively over taller players, led him to numerous NBA scoring records, several of which still stand.

The 71 points Baylor scored on November 15, 1960, was a record at the time; it was also a team record that would not be surpassed until Kobe Bryant scored 81 points against the Toronto Raptors in January 2006. The 61 points he scored in Game 5 of the NBA Finals in 1962 is still an NBA Finals record. Over his career, he averaged 27.4 points and 4.3 assists per game. An underrated rebounder, Baylor averaged 13.5 rebounds per game during his career, including a remarkable 19.8 rebounds per game during the 1960–61 season—a season average exceeded by only five other players in NBA history, all of whom were 6 ft 8 in (2.03 m) or taller.

A 10-time All-NBA First Team selection and 11-time NBA All-Star, Baylor was elected to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1977. He was named to the NBA 35th Anniversary All-Time Team in 1980, the NBA 50th Anniversary All-Time Team in 1996 and the NBA 75th Anniversary Team in 2021. in 2009, SLAM Magazine ranked him number 11 among its Top 50 NBA players of all time. In 2022, to commemorate the NBA's 75th Anniversary The Athletic ranked their top 75 players of all time, and named Baylor as the 23rd greatest player in NBA history. He is often listed as the greatest NBA player never to win a championship, although the Lakers did give Baylor a championship ring for his contributions at the start of the 1971–72 season.

Fifty-one years after Baylor left Seattle University, they named its basketball court in honor of him on November 19, 2009. The Redhawks now play on the Elgin Baylor Court in Seattle's KeyArena. The Redhawks also host the annual Elgin Baylor Classic. In June 2017, The College of Idaho had Baylor as one of the inaugural inductees into the school's Hall of Fame.

The first biography of Baylor was written by Slam Online contributor Bijan C. Bayne in 2015, and published by Rowman and Littlefield.

On April 6, 2018, a statue of Baylor, designed by Gary Tillery and Omri Amrany, was unveiled at the Staples Center prior to a Lakers game against the Minnesota Timberwolves.

NBA career statistics

| GP | Games played | GS | Games started | MPG | Minutes per game |

| FG% | Field goal percentage | 3P% | 3-point field goal percentage | FT% | Free throw percentage |

| RPG | Rebounds per game | APG | Assists per game | SPG | Steals per game |

| BPG | Blocks per game | PPG | Points per game | Bold | Career high |

| * | Led the league |

| Year | Team | GP | MPG | FG% | FT% | RPG | APG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1958–59 | Minneapolis | 70 | 40.8 | .408 | .777 | 15.0 | 4.1 | 24.9 |

| 1959–60 | Minneapolis | 70 | 41.0 | .424 | .732 | 16.4 | 3.5 | 29.6 |

| 1960–61 | L.A. Lakers | 73 | 42.9 | .430 | .783 | 19.8 | 5.1 | 34.8 |

| 1961–62 | L.A. Lakers | 48 | 44.4 | .428 | .754 | 18.6 | 4.6 | 38.3 |

| 1962–63 | L.A. Lakers | 80* | 42.1 | .453 | .837 | 14.3 | 4.8 | 34.0 |

| 1963–64 | L.A. Lakers | 78 | 40.6 | .425 | .804 | 12.0 | 4.4 | 25.4 |

| 1964–65 | L.A. Lakers | 74 | 41.3 | .401 | .792 | 12.8 | 3.8 | 27.1 |

| 1965–66 | L.A. Lakers | 65 | 30.4 | .401 | .739 | 9.6 | 3.4 | 16.6 |

| 1966–67 | L.A. Lakers | 70 | 38.7 | .429 | .813 | 12.8 | 3.1 | 26.6 |

| 1967–68 | L.A. Lakers | 77 | 39.3 | .443 | .786 | 12.2 | 4.6 | 26.0 |

| 1968–69 | L.A. Lakers | 76 | 40.3 | .447 | .743 | 10.6 | 5.4 | 24.8 |

| 1969–70 | L.A. Lakers | 54 | 41.0 | .486 | .773 | 10.4 | 5.4 | 24.0 |

| 1970–71 | L.A. Lakers | 2 | 28.5 | .421 | .667 | 5.5 | 1.0 | 10.0 |

| 1971–72 | L.A. Lakers | 9 | 26.6 | .433 | .815 | 6.3 | 2.0 | 11.8 |

| Career | 846 | 40.0 | .431 | .780 | 13.5 | 4.3 | 27.4 | |

| All-Star | 11 | 29.2 | .427 | .796 | 9.0 | 3.5 | 19.8 | |

Source:

| Year | Team | GP | MPG | FG% | FT% | RPG | APG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1959 | Minneapolis | 13 | 42.8 | .403 | .770 | 12.0 | 3.3 | 25.5 |

| 1960 | Minneapolis | 9 | 45.3 | .474 | .840 | 14.1 | 3.4 | 33.4 |

| 1961 | L.A. Lakers | 12 | 45.0 | .470 | .824 | 15.3 | 4.6 | 38.1 |

| 1962 | L.A. Lakers | 13 | 43.9 | .438 | .774 | 17.7 | 3.6 | 38.6 |

| 1963 | L.A. Lakers | 13 | 43.2 | .442 | .825 | 13.6 | 4.5 | 32.6 |

| 1964 | L.A. Lakers | 5 | 44.2 | .378 | .775 | 11.6 | 5.6 | 24.2 |

| 1965 | L.A. Lakers | 1 | 5.0 | .000 | – | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| 1966 | L.A. Lakers | 14 | 41.9 | .442 | .810 | 14.1 | 3.7 | 26.8 |

| 1967 | L.A. Lakers | 3 | 40.3 | .368 | .750 | 13.0 | 3.0 | 23.7 |

| 1968 | L.A. Lakers | 15 | 42.2 | .468 | .679 | 14.5 | 4.0 | 28.5 |

| 1969 | L.A. Lakers | 18 | 35.6 | .385 | .630 | 9.2 | 4.1 | 15.4 |

| 1970 | L.A. Lakers | 18 | 37.1 | .466 | .741 | 9.6 | 4.6 | 18.7 |

| Career | 134 | 41.1 | .439 | .769 | 12.9 | 4.0 | 27.0 | |

Source:

Head coaching record

| Regular season | G | Games coached | W | Games won | L | Games lost | W–L % | Win–loss % |

| Playoffs | PG | Playoff games | PW | Playoff wins | PL | Playoff losses | PW–L % | Playoff win–loss % |

| Team | Year | G | W | L | W–L% | Finish | PG | PW | PL | PW–L% | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Orleans | 1974–75 | 1 | 0 | 1 | .000 | (interim) | – | – | – | – | – |

| New Orleans | 1976–77 | 56 | 21 | 35 | .375 | 5th in central | – | – | – | – | Missed Playoffs |

| New Orleans | 1977–78 | 82 | 39 | 43 | .476 | 5th in central | – | – | – | – | Missed Playoffs |

| New Orleans | 1978–79 | 82 | 26 | 56 | .317 | 6th in central | – | – | – | – | Missed Playoffs |

| Career | 221 | 86 | 135 | .389 | – | – | – | – |

Source:

See also

- List of NBA career scoring leaders

- List of NBA career rebounding leaders

- List of NBA career free throw scoring leaders

- List of NBA career triple-double leaders

- List of NBA career playoff scoring leaders

- List of NBA career playoff rebounding leaders

- List of NBA career playoff free throw scoring leaders

- List of NBA career playoff triple-double leaders

- List of NBA single-game scoring leaders

- List of NBA single-game playoff scoring leaders

- List of NBA rookie single-season scoring leaders

- List of NCAA Division I men's basketball season rebounding leaders

- List of NCAA Division I men's basketball career rebounding leaders

- List of NCAA Division I men's basketball players with 30 or more rebounds in a game

- List of NCAA Division I men's basketball players with 2000 points and 1000 rebounds

- List of NCAA Division I men's basketball players with 60 or more points in a game

References

- "Elgin Baylor: Complete Bio". nba.com. Retrieved February 3, 2008.

- "Hall of Famers". Basketball Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on February 15, 2011. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- "NBA at 50: Top 50 Players". NBA.com. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- NBA 75th Anniversary Team

- "Clippers players shocked Baylor is out". Ocregister.com. October 8, 2008. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ Fisher, James (2016) . "Elgin Baylor: The First Modern Professional Basketball Player". In Hoffmann, Frank; Batchelor, Robert P.; Manning, Martin J. (eds.). Basketball in America: From the Playgrounds to Jordan's Game and Beyond. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315043869. ISBN 978-1-315-04386-9.

- ^ Smith, Harrison (March 22, 2021). "Elgin Baylor, highflying Hall of Famer for the Los Angeles Lakers, dies at 86". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- Bayne, Bijan C. (August 13, 2015). Elgin Baylor: The Man Who Changed Basketball. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442245716.

- ^ Schwartz, Larry. "Before Michael, there was Elgin". espn.com. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- ^ McKenna, Dave (July 2, 1999). "Elgin Baylor, Absentee Legend". Washington City Paper. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- Schilling, Dave (April 6, 2018). "Kobe Before Kobe, LeBron Before LeBron: Elgin Baylor Finally Gets His Due". Bleacher Report. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ Bayne, Bijan (August 13, 2015). Elgin Baylor The Man Who Changed Basketball. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 2–6. ISBN 9781442245716. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ Goldstein, Richard (March 22, 2021). "Elgin Baylor, Acrobatic Hall of Famer in N.B.A., Dies at 86". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- NBA Register: 1986–87 Edition. The Sporting News Publishing Company. 1986. p. 287. ISBN 9780892042272.

- "Los Angeles Lakers star and former LA Clippers exec Elgin Baylor dies at 86". ESPN. March 22, 2021. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ "#22 ELGIN BAYLOR". NBA.com. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- NBA Register: 1986–87 Edition. The Sporting News Publishing Company. 1986. p. 289. ISBN 9780892042272.

- Knoblauch, A., "Greatest sports figures in L.A. history, No. 17: Elgin Baylor", Los Angeles Times, October 14, 2011.

- ^ "Lakers legend and Hall of Famer Elgin Baylor dead at 86". NBA. March 22, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2022.

- ^ McCallum, Jack (2018). "The Terrific Tandem of West and Baylor". Golden Days: West's Lakers, Steph's Warriors, and the California Dreamers Who Reinvented Basketball. Random House. ISBN 978-0-399-17909-9.

- "How many NBA Finals sweeps have there been?". June 3, 2018.

- "Clippers' Baylor named executive of year". ESPN. May 17, 2006. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ Liz, Roscher (March 22, 2021). "Elgin Baylor, legendary Hall of Famer and Lakers star, dies at 86". Yahoo Sports. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- Abrams, Jonathan (March 26, 2009). "Elgin Baylor and His Lawsuit Against the Clippers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- Elgin Baylor Sues Los Angeles Clippers for Employment Discrimination ESPN.com, February 11, 2009.

- Lance Pugmire (March 4, 2011). "Elgin Baylor drops racial discrimination claim in suit against L.A. Clippers". Articles.latimes.com. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- Lance Pugmire, "Elgin Baylor's lawsuit rejected by Los Angeles County jury", Los Angeles Times, March 30, 2011.

- Dimitrije Curcic (May 14, 2019). "67 Years of Height Evolution in the NBA - In-depth Research". runrepeat.com. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- Trivic, Filip (April 7, 2020). "Elgin's 38-19-5 more implausible than Wilt's 50 a game or Oscar's triple-double". Basketball Network. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- "NBA All-Time Rebounds Leaders: Career Per Game Average in the Regular Season". Land of Basketball. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- "NBA 75: At No. 23, Elgin Baylor used his strength and grace to create magic above the rim".

- "The 10 Greatest NBA Players With No Championship Jewelry". Dimemag.com. May 18, 2011. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- Barry Petchesky (May 29, 2013). "The Greatest NBA Player To Never Win A Title Is Auctioning Off His Championship Ring. (What?)". Deadspin.com. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- "Wisch: Top 5 Players To Never Win An NBA Title « CBS Chicago". Chicago.cbslocal.com. June 14, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- Rains, B.J. (June 2, 2017). "NBA Hall of Famer Elgin Baylor returns to Caldwell for induction to College of Idaho Hall of Fame". Idaho Press. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- Nelson, Murry (Spring 2016). "Elgin Baylor: The Man Who Changed Basketball by Bijan C. Bayne (review)". Journal of Sport History. 43 (1): 110–111. doi:10.5406/jsporthistory.43.1.110. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- Oram, Bill (April 6, 2018). "Elgin Baylor 'humbled' as Lakers unveil statue outside Staples Center". OC Register. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ "Elgin Baylor Stats". Basketball-Reference.com. Sports Reference. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- "Elgin Baylor Coaching Record". Basketball-Reference.com. Sports Reference. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

External links

- Career statistics from NBA.com

and Basketball Reference

and Basketball Reference - NBA.com bio

- Elgin Baylor at the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame

- Elgin Baylor at IMDb

- Elgin Baylor at Find a Grave

- 1934 births

- 2021 deaths

- 20th-century African-American sportsmen

- 21st-century African-American sportsmen

- African-American basketball coaches

- African-American sports executives and administrators

- African-American United States Army personnel

- All-American college men's basketball players

- Amateur Athletic Union men's basketball players

- American men's basketball coaches

- American men's basketball players

- American military sports players

- American sports executives and administrators

- Basketball coaches from Washington, D.C.

- Basketball players from Washington, D.C.

- Burials at Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Hollywood Hills)

- College basketball announcers in the United States

- College of Idaho Coyotes men's basketball players

- First overall NBA draft picks

- Los Angeles Clippers executives

- Los Angeles Lakers players

- Military personnel from Washington, D.C.

- Minneapolis Lakers draft picks

- Minneapolis Lakers players

- Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame inductees

- NBA All-Stars

- NBA broadcasters

- NBA championship–winning players

- NBA general managers

- NBA players with retired numbers

- New Orleans Jazz assistant coaches

- New Orleans Jazz head coaches

- Seattle Redhawks men's basketball players

- Small forwards

- United States Army reservists

- United States Army soldiers