Bandwidth is the difference between the upper and lower frequencies in a continuous band of frequencies. It is typically measured in unit of hertz (symbol Hz).

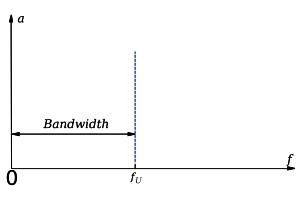

It may refer more specifically to two subcategories: Passband bandwidth is the difference between the upper and lower cutoff frequencies of, for example, a band-pass filter, a communication channel, or a signal spectrum. Baseband bandwidth is equal to the upper cutoff frequency of a low-pass filter or baseband signal, which includes a zero frequency.

Bandwidth in hertz is a central concept in many fields, including electronics, information theory, digital communications, radio communications, signal processing, and spectroscopy and is one of the determinants of the capacity of a given communication channel.

A key characteristic of bandwidth is that any band of a given width can carry the same amount of information, regardless of where that band is located in the frequency spectrum. For example, a 3 kHz band can carry a telephone conversation whether that band is at baseband (as in a POTS telephone line) or modulated to some higher frequency. However, wide bandwidths are easier to obtain and process at higher frequencies because the § Fractional bandwidth is smaller.

Overview

Bandwidth is a key concept in many telecommunications applications. In radio communications, for example, bandwidth is the frequency range occupied by a modulated carrier signal. An FM radio receiver's tuner spans a limited range of frequencies. A government agency (such as the Federal Communications Commission in the United States) may apportion the regionally available bandwidth to broadcast license holders so that their signals do not mutually interfere. In this context, bandwidth is also known as channel spacing.

For other applications, there are other definitions. One definition of bandwidth, for a system, could be the range of frequencies over which the system produces a specified level of performance. A less strict and more practically useful definition will refer to the frequencies beyond which performance is degraded. In the case of frequency response, degradation could, for example, mean more than 3 dB below the maximum value or it could mean below a certain absolute value. As with any definition of the width of a function, many definitions are suitable for different purposes.

In the context of, for example, the sampling theorem and Nyquist sampling rate, bandwidth typically refers to baseband bandwidth. In the context of Nyquist symbol rate or Shannon-Hartley channel capacity for communication systems it refers to passband bandwidth.

The Rayleigh bandwidth of a simple radar pulse is defined as the inverse of its duration. For example, a one-microsecond pulse has a Rayleigh bandwidth of one megahertz.

The essential bandwidth is defined as the portion of a signal spectrum in the frequency domain which contains most of the energy of the signal.

x dB bandwidth

In some contexts, the signal bandwidth in hertz refers to the frequency range in which the signal's spectral density (in W/Hz or V/Hz) is nonzero or above a small threshold value. The threshold value is often defined relative to the maximum value, and is most commonly the 3 dB point, that is the point where the spectral density is half its maximum value (or the spectral amplitude, in or , is 70.7% of its maximum). This figure, with a lower threshold value, can be used in calculations of the lowest sampling rate that will satisfy the sampling theorem.

The bandwidth is also used to denote system bandwidth, for example in filter or communication channel systems. To say that a system has a certain bandwidth means that the system can process signals with that range of frequencies, or that the system reduces the bandwidth of a white noise input to that bandwidth.

The 3 dB bandwidth of an electronic filter or communication channel is the part of the system's frequency response that lies within 3 dB of the response at its peak, which, in the passband filter case, is typically at or near its center frequency, and in the low-pass filter is at or near its cutoff frequency. If the maximum gain is 0 dB, the 3 dB bandwidth is the frequency range where attenuation is less than 3 dB. 3 dB attenuation is also where power is half its maximum. This same half-power gain convention is also used in spectral width, and more generally for the extent of functions as full width at half maximum (FWHM).

In electronic filter design, a filter specification may require that within the filter passband, the gain is nominally 0 dB with a small variation, for example within the ±1 dB interval. In the stopband(s), the required attenuation in decibels is above a certain level, for example >100 dB. In a transition band the gain is not specified. In this case, the filter bandwidth corresponds to the passband width, which in this example is the 1 dB-bandwidth. If the filter shows amplitude ripple within the passband, the x dB point refers to the point where the gain is x dB below the nominal passband gain rather than x dB below the maximum gain.

In signal processing and control theory the bandwidth is the frequency at which the closed-loop system gain drops 3 dB below peak.

In communication systems, in calculations of the Shannon–Hartley channel capacity, bandwidth refers to the 3 dB-bandwidth. In calculations of the maximum symbol rate, the Nyquist sampling rate, and maximum bit rate according to the Hartley's law, the bandwidth refers to the frequency range within which the gain is non-zero.

The fact that in equivalent baseband models of communication systems, the signal spectrum consists of both negative and positive frequencies, can lead to confusion about bandwidth since they are sometimes referred to only by the positive half, and one will occasionally see expressions such as , where is the total bandwidth (i.e. the maximum passband bandwidth of the carrier-modulated RF signal and the minimum passband bandwidth of the physical passband channel), and is the positive bandwidth (the baseband bandwidth of the equivalent channel model). For instance, the baseband model of the signal would require a low-pass filter with cutoff frequency of at least to stay intact, and the physical passband channel would require a passband filter of at least to stay intact.

Relative bandwidth

See also: Antenna (radio) § Bandwidth, and Antenna measurement § BandwidthThe absolute bandwidth is not always the most appropriate or useful measure of bandwidth. For instance, in the field of antennas the difficulty of constructing an antenna to meet a specified absolute bandwidth is easier at a higher frequency than at a lower frequency. For this reason, bandwidth is often quoted relative to the frequency of operation which gives a better indication of the structure and sophistication needed for the circuit or device under consideration.

There are two different measures of relative bandwidth in common use: fractional bandwidth () and ratio bandwidth (). In the following, the absolute bandwidth is defined as follows, where and are the upper and lower frequency limits respectively of the band in question.

Fractional bandwidth

Fractional bandwidth is defined as the absolute bandwidth divided by the center frequency (),

The center frequency is usually defined as the arithmetic mean of the upper and lower frequencies so that, and

However, the center frequency is sometimes defined as the geometric mean of the upper and lower frequencies, and

While the geometric mean is more rarely used than the arithmetic mean (and the latter can be assumed if not stated explicitly) the former is considered more mathematically rigorous. It more properly reflects the logarithmic relationship of fractional bandwidth with increasing frequency. For narrowband applications, there is only marginal difference between the two definitions. The geometric mean version is inconsequentially larger. For wideband applications they diverge substantially with the arithmetic mean version approaching 2 in the limit and the geometric mean version approaching infinity.

Fractional bandwidth is sometimes expressed as a percentage of the center frequency (percent bandwidth, ),

Ratio bandwidth

Ratio bandwidth is defined as the ratio of the upper and lower limits of the band,

Ratio bandwidth may be notated as . The relationship between ratio bandwidth and fractional bandwidth is given by, and

Percent bandwidth is a less meaningful measure in wideband applications. A percent bandwidth of 100% corresponds to a ratio bandwidth of 3:1. All higher ratios up to infinity are compressed into the range 100–200%.

Ratio bandwidth is often expressed in octaves (i.e., as a frequency level) for wideband applications. An octave is a frequency ratio of 2:1 leading to this expression for the number of octaves,

Noise equivalent bandwidth

The noise equivalent bandwidth (or equivalent noise bandwidth (enbw)) of a system of frequency response is the bandwidth of an ideal filter with rectangular frequency response centered on the system's central frequency that produces the same average power outgoing when both systems are excited with a white noise source. The value of the noise equivalent bandwidth depends on the ideal filter reference gain used. Typically, this gain equals at its center frequency, but it can also equal the peak value of .

The noise equivalent bandwidth can be calculated in the frequency domain using or in the time domain by exploiting the Parseval's theorem with the system impulse response . If is a lowpass system with zero central frequency and the filter reference gain is referred to this frequency, then:

The same expression can be applied to bandpass systems by substituting the equivalent baseband frequency response for .

The noise equivalent bandwidth is widely used to simplify the analysis of telecommunication systems in the presence of noise.

Photonics

In photonics, the term bandwidth carries a variety of meanings:

- the bandwidth of the output of some light source, e.g., an ASE source or a laser; the bandwidth of ultrashort optical pulses can be particularly large

- the width of the frequency range that can be transmitted by some element, e.g. an optical fiber

- the gain bandwidth of an optical amplifier

- the width of the range of some other phenomenon, e.g., a reflection, the phase matching of a nonlinear process, or some resonance

- the maximum modulation frequency (or range of modulation frequencies) of an optical modulator

- the range of frequencies in which some measurement apparatus (e.g., a power meter) can operate

- the data rate (e.g., in Gbit/s) achieved in an optical communication system; see bandwidth (computing).

A related concept is the spectral linewidth of the radiation emitted by excited atoms.

See also

Notes

- The information capacity of a channel depends on noise level as well as bandwidth – see Shannon–Hartley theorem. Equal bandwidths can carry equal information only when subject to equal signal-to-noise ratios.

References

- Jeffrey A. Nanzer, Microwave and Millimeter-wave Remote Sensing for Security Applications, pp. 268-269, Artech House, 2012 ISBN 1608071723.

- Sundararajan, D. (4 March 2009). A Practical Approach to Signals and Systems. John Wiley & Sons. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-470-82354-5.

- Van Valkenburg, M. E. (1974). Network Analysis (3rd ed.). Prentice-Hall. pp. 383–384. ISBN 0-13-611095-9. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- Stutzman, Warren L.; Theiele, Gary A. (1998). Antenna Theory and Design (2nd ed.). New York. ISBN 0-471-02590-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Hans G. Schantz, The Art and Science of Ultrawideband Antennas, p. 75, Artech House, 2015 ISBN 1608079562

- Jeruchim, M. C.; Balaban, P.; Shanmugan, K. S. (2000). Simulation of Communication Systems. Modeling, Methodology, and Techniques (2nd ed.). Kluwer Academic. ISBN 0-306-46267-2.

or

or  , is 70.7% of its maximum). This figure, with a lower threshold value, can be used in calculations of the lowest sampling rate that will satisfy the

, is 70.7% of its maximum). This figure, with a lower threshold value, can be used in calculations of the lowest sampling rate that will satisfy the  , where

, where  is the total bandwidth (i.e. the maximum passband bandwidth of the carrier-modulated RF signal and the minimum passband bandwidth of the physical passband channel), and

is the total bandwidth (i.e. the maximum passband bandwidth of the carrier-modulated RF signal and the minimum passband bandwidth of the physical passband channel), and  is the positive bandwidth (the baseband bandwidth of the equivalent channel model). For instance, the baseband model of the signal would require a

is the positive bandwidth (the baseband bandwidth of the equivalent channel model). For instance, the baseband model of the signal would require a  ) and ratio bandwidth (

) and ratio bandwidth ( ). In the following, the absolute bandwidth is defined as follows,

). In the following, the absolute bandwidth is defined as follows,

where

where  and

and  are the upper and lower frequency limits respectively of the band in question.

are the upper and lower frequency limits respectively of the band in question.

),

),

and

and

and

and

),

),

. The relationship between ratio bandwidth and fractional bandwidth is given by,

. The relationship between ratio bandwidth and fractional bandwidth is given by,

and

and

of the system with frequency response

of the system with frequency response  .

. at its center frequency, but it can also equal the peak value of

at its center frequency, but it can also equal the peak value of  . If

. If