Expectancy violations theory (EVT) is a theory of communication that analyzes how individuals respond to unanticipated violations of social norms and expectations. The theory was proposed by Judee K. Burgoon in the late 1970s and continued through the 1980s and 1990s as "nonverbal expectancy violations theory", based on Burgoon's research studying proxemics. Burgoon's work initially analyzed individuals' allowances and expectations of personal distance and how responses to personal distance violations were influenced by the level of liking and relationship to the violators. The theory was later changed to its current name when other researchers began to focus on violations of social behavior expectations beyond nonverbal communication.

This theory sees communication as an exchange of behaviors, where one individual's behavior can be used to violate the expectations of another. Participants in communication will perceive the exchange either positively or negatively, depending upon an existing personal relationship or how favorably the violation is perceived. Violations of expectancies cause arousal and compel the recipient to initiate a series of cognitive appraisals of the violation. The theory predicts that expectancies influence the outcome of the communication interaction as either positive or negative and predicts that positive violations increase the attraction of the violator and negative violations decrease the attraction of the violator.

Beyond proxemics and examining how people interpret violations in many given communicative contexts, EVT also makes specific predictions about individuals' reaction to given expectation violations: individuals reciprocate or match someone's unexpected behavior, and they also compensate or counteract by doing the opposite of the communicator's behavior.

Components

The EVT examines three main components in interpersonal communication situations: Expectancies, communicator reward valence, and violation valence.

Expectancy

Expectancy refers to what an individual anticipates will happen in a given situation. Expectancies are primarily based upon social norms and specific characteristics and idiosyncrasies of the communicators.

Burgoon (1978) notes that people do not view others' behaviors as random. Rather, they have various expectations of how others should think and behave. EVT proposes that observation and interaction with others leads to expectancies. The two types of expectancies noted are predictive and prescriptive. Predictive expectations are "behaviors we expect to see because they are the most typical," (Houser, 2005) and vary across cultures. They let people know what to expect based upon what typically occurs within the context of a particular environment and relationship. For example, a husband and wife may have an evening routine in which the husband always washes the dishes. If he were to ignore the dirty dishes one night, this might be seen as a predictive discrepancy. Prescriptive expectations, on the other hand, are based upon "beliefs about what behaviors should be performed" and "what is needed and desired" (Houser, 2005). If a person walks into a police department to report a crime, the person will have an expectation that the police will file a report and follow up with an investigation.

Judee Burgoon and Jerold Hale categorize existing expectations into two types based on the process of interaction: pre-interactional and interactional expectations. Pre-interactional expectations are the package of knowledge and skills a person already has before entering a conversation. For example, aggressive attitudes may not be expected if previous experience has not included dealing with similar attitudes. Interactional expectations form the abilities equipped to conduct an ongoing conversation. Proper reactions and nodding to show listening behaviors are expected in a conversation.

When the theory was first proposed, EVT identified three factors which influence a person's expectations: Interactant variables, environmental variables, and variables related to the nature of the interaction. Interactant variables are the traits of those persons involved in the communication, such as sex, attractiveness, race, culture, status, and age. Environmental variables include the amount of space available and the nature of the territory surrounding the interaction. Interaction variables include social norms, purpose of the interaction, and formality of the situation.

These factors later evolved into communicator characteristics, relational characteristics, and context. Communicator characteristics include personal features such as an individual's appearance, personality and communication style. It also includes factors such as age, sex, and ethnic background. Relational characteristics refer to factors such as similarity, familiarity, status and liking. The type of relationship one individual shares within another (e.g. romantic, business or platonic), the previous experiences shared between the individuals, and how close they are with one another are also relational characteristics that influence expectations. Context encompasses both environment and interaction characteristics. Communicator characteristics lead to distinctions between males and females in assessing the extent to which their nonverbal expressions of power and dominance effect immediacy behaviors. Immediacy cues such as conversational distance, lean, body orientation, gaze, and touch may differ between the genders as they create psychological closeness or distance between the interactants.

Behavioural expectations may also shift depending on the environment one is experiencing. For example, a visit to a church will produce different expectations than a social function. The expected violations will therefore be altered. Similarly, expectations differ based on culture. In Europe, one may expect to be greeted with three kisses on alternating cheeks, but this is not the case in the United States.

Communicator reward valence

The communicator reward valence is an evaluation one makes about the person who committed a violation of expectancy. Em Griffin summarizes the concept behind communicator reward valence as "the sum of positive and negative attributes brought to the encounter plus the potential to reward or punish in the future". The social exchange theory explains that individuals seek to reward some and seek to avoid punishing others. When one individual interacts with another, Burgoon believes he or she will assess the "positive and negative attributes that person brings to the encounter". If the person has the ability to reward or punish the receiver in the future, then the person has a positive reward valence. Rewards simply refer to the person's ability to provide a want or need. It can be represented by several features, such as communicators with high social class, reputation, knowledge, positive emotional support, physical attractiveness, and so on. The term 'communicator reward valence' is used to describe the results of this assessment. For example, people will feel encouraged during conversation when the listener is nodding, making eye contact, and responding actively. Conversely, if the listener is avoiding eye contact, yawning, and texting, it is implied they have no interest in the interaction and the speaker may feel violated. The deviation of expectations does not always yield negative results, which depends on the degree of reward held by the reward communicator. An action might be viewed as positive by a high-reward communicator, as the same action might be seen as negative by a lower-reward communicator.

When examining the context, relationship, and communicator's characteristics in a given encounter, individuals will arrive at an expectation for how that person should behave. Changing even one of these expectancy variables may lead to a different expectation. For example, in different cultures, directly looking into a speaker's eyes, especially in a personal conversation, can represent distinct meanings.

Violation valence

Behavior violations arouse and distract, calling attention to the qualities of the violator and the relationship between the interactants. A key component of EVT is the notion of violation valence, or the association the receiver places on the behavior violation. A violatee's response to an expectancy violation can be positive or negative, and is dependent on two conditions: positive or negative interpretation of the behavior and the nature (rewardingness) of the violator. The nature of the violator is evaluated through many categories – attractiveness, prestige, ability to provide resources, or associated relationship. For instance, a violation of one's personal distance might have more positive valence if committed by a wealthy, powerful, physically appealing member of the opposite sex than a filthy, poor, homeless person with foul breath. The evaluation of the violation is based upon the relationship between the particular behavior and the valence of the actor. A person's preinteractional expectancies, especially personal attributes, may cause a perceiver to evaluate the communication behavior of a target differently in terms of assigning positive and negative valenced expectancies.

Another perspective of violation valence is that the perceived positive or negative value assigned to a breach of expectations is inconsequential of who the violator is. This perspective places much greater weight on the act of the breach itself than the violator.

Arousal

Expectancy violations refer to actions which are noticeably discrepant from an expectancy and are classified as outside the range of expectancy. The term 'arousal value' is used to describe the consequences of deviations from expectations. When individuals' expectations are violated, their interests or attentions are aroused.

When arousal occurs, one's interest or attention to the deviation increases, resulting in less attention paid to the message and more attention to the source of the arousal. There are two kinds of arousals. Cognitive arousal is an idea that people will be mentally aware of the violation. Physical occurs when people have body actions and behaviors in response to the deviations from their expectations. For example, when one experiences physical arousal, he or she chooses to move out of the physical space, keep the distance with other conversationalists, or stretch his or her body. Beth Le Poire and Judee Burgoon research to examine physical arousal in conversation. The result shows that after participants report their cognitive arousal, physically speaking, their heart rate decreases and pulse volume increase.

Threat threshold

The occurrence of arousal is aligned with threats. Burgoon introduced the term "threat threshold" to explain that people have different levels of tolerance about distant violations. The threat threshold is high when people feel good even if they keep a very close distance with the violator, whereas people with low threat threshold will be sensitive and uncomfortable about the closeness of distance with the violator.

Theoretical assumptions and viewpoints

Propositions

After assessing expectancy, violation valence, and communicator reward valence of a given situation, it becomes possible to make rather specific predictions about whether the individual who perceived the violation will reciprocate or compensate the behavior in question. Guerrero and Burgoon noticed that predictable patterns develop when considering reward valence and violation valence together. Specifically, if the violation valence is perceived as positive and the communicator reward valence is also perceived as positive, the theory predicts individuals will reciprocate the positive behavior. Similarly, if one perceives the violation valence as negative and the communicator reward valence as negative, the theory again predicts that one will reciprocate the negative behavior. Thus, if a disliked coworker is grouchy and unpleasant, people will likely reciprocate and be unpleasant in return.

Conversely, if one perceives a negative violation valence but views the communicator reward valence as positive, it is likely that the person will compensate for his or her partner's negative behavior. For example, imagine a supervisor appears sullen and throws a stack of papers in front of an employee. Rather than grunt back, EVT predicts that the employee will compensate for the boss's negativity, perhaps by asking if everything is okay. More difficult to predict, however, is the situation in which a person who is viewed unfavorably violates another with positive behavior. In this situation, the receiver may reciprocate, giving the person the "benefit of the doubt".

The assumptions discussed thus far can be summarized into six major propositions posited by EVT:

- People develop expectations about verbal and nonverbal communication behavior from other people.

- Violations of these expectations cause arousal and distraction, further leading the receiver to shift his or her attention to the other, the relationship, and the meaning of the violation.

- Communicator reward valence determines the interpretation of ambiguous communication.

- Communicator reward valence determines how the behavior is evaluated.

- Violation valences are determined by three factors:

- The evaluation of the behavior

- Whether or not the behavior is more or less favorable than the expectation. A positive violation occurs when the behavior is more favorable than the expectation. A negative violation occurs when the behavior is less favorable.

- The magnitude of the violation.

- Positive violations produce more favorable outcomes than behavior that matches expectations, and negative violations produce more unfavorable outcomes than behavior that matches expectations.

Needs for personal space and affiliation

EVT builds upon a number of communication axioms. EVT assumes that humans have two competing needs: A need for personal space and a need for affiliation. Specifically, humans all need a certain amount of personal space, also referred to as distance or privacy. People also desire a certain amount of closeness with others, or affiliation. EVT seeks to explain 'personal space', and the meanings that are formed when expectations of appropriate personal space are infringed or violated.

Another feature of personal space is territoriality. Territoriality refers to behavior which "is characterized by identification with a geographic area in a way that indicates ownership" (Hall, 1966). In humans, territoriality refers to an individual's sense of ownership over physical items, space, objects or ideas, and defensive behavior in response to territorial invasions. Territoriality involves three territory types: Primary territories, secondary territories and public territories. Primary territories are considered exclusive to an individual. Secondary territories are objects, spaces or places which "can be claimed temporarily" (Hall, 1966), but are neither central to the individual's life nor are exclusively owned. Public territories are "available to almost anyone for temporary ownership". Territoriality is frequently accompanied by prevention and reaction. When an individual perceives one of their needs has been compromised, EVT predicts that they will react. For instance, when an offensive violation occurs, the individual tends to react as though protecting their territory.

Proxemics

EVT offers an opportunity to study how individuals communicate through personal space. This part of the theory explains the notion of "personal space" and an individual's reactions to others who appear to "violate" their sense of personal space. What people define as personal space, however, varies from culture to culture and from person to person. The "success" or "failure" of violations are linked to perceived attraction, credibility, influence and involvement. The context and purpose of interaction are relevant, as are the communicator characteristics of gender, relationships, status, social class, ethnicity and culture. When it comes to different interactions between people, what each person expects out of the interaction will influence their individual willingness to risk violation. If a person feels comfortable in a situation, they are more likely to risk violation, and in turn will be rewarded for it.

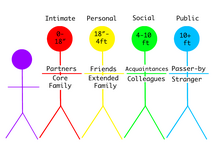

Introduced by Edward Hall in 1966, proxemics deals with the amount of distance between people as they interact with one another. Spatial distance during an interaction can be an indication of what type of relationship exists between the people involved.

There are 4 different personal zones defined by Hall. These zones include:

- Intimate distance: (0–18 inches) – This distance is for close, intimate encounters. Normally core family, close friends, lovers, or pets. People will normally share a unique level of comfort with one another.

- Personal distance: (18 inches – 4 feet) – Reserved for conversations with friends, extended family, associates, and group discussions. The personal distance will give each person more space compared with the intimate distance, but is still close enough to involve touching one another.

- Social distance: (4–10 feet) – This distance is reserved for newly formed groups, and new acquaintances and colleagues one may have just met. People generally do not engage physically with one another within this section.

- Public distance: (10 feet to infinity) – Reserved for a public setting with large audiences, strangers, speeches, and theaters.

Many different cultures are influenced by proxemics in different ways and respond differently to the same situation. In some cultures, those who have not formed close relationships may greet each other with kisses on the cheek, engaging one another well within the intimate range of proxemics. In other cultures, a custom greeting is a handshake which maintains a physical separation but is well within personal distance. Across the proxemic zones, actions can be interpreted differently among different cultures. For example, Japanese people do not address others by their first names unless they have been given permission. Calling someone by their first name in Japan without permission is considered an insult. In the Japanese culture, they address people using their last name and 'san', which is equivalent to 'Mr.', 'Mrs.' and 'Ms.' in the English language. The way Japanese people address each other is an example of a verbal proxemic zone. A Japanese person allowing another to call them by their first name is an example of intimate distance, because this is a privilege extended only someone very close to them.

Applications

Interpersonal communication

It is important to note that EVT can apply to both non-relational interaction and close relationships. In 1998, more than twenty years after the theory was first published, several studies were conducted to catalog the types of expectancy violations commonly found in close relationships.

Participants in friendships and romantic relationships were asked to think about the last time their friend or partner did or said something unexpected. It was emphasized that the unexpected event could be either positive or negative. Participants reported events that had occurred, on average, five days earlier, suggesting that unexpected behaviors happen often in relationships. Some of the behaviors reported were relatively mundane, and others were quite serious. The outcome of the list was a list of nine general categories of expectation violations that commonly occur in relationships.

- Support or confirmation is an act that provides social support in a particular time of need, such as sitting with a friend who is sick.

- Criticism or accusation is critical of the receiver and accuse the individual of an offense. These are violations because they are accusations not expected. An example is a ball player telling a teammate he should have caught the ball rather than supportively giving him or her a slap on the back and offering words of encouragement.

- Relationship intensification or escalation intensifies the commitment of the communicator. For instance, saying "I love you" signifies a deepening of a romantic relationship.

- Relationship de-escalation signifies a decrease in commitment of the communicator. An example might be spending more time apart.

- Relational transgressions are violations of the perceived rules of the relationship. Examples include having an affair, deception, or being disloyal.

- Acts of devotion are unexpected overtures that imply specialness in the relationship. Buying flowers for no particular occasion falls into this category.

- Acts of disregard show that the partner is unimportant. This could be as simple as excluding a partner or a friend from a collective activity.

- Gestures of inclusion are actions that show an unexpected interest in having the other included in special activities or life. Examples include invitations to spend a special holiday with someone, disclosure of personal information, or inviting the partner to meet one's family.

- Uncharacteristic relational behavior is unexpected action that is not consistent with the partner's perception of the relationship. A common example is one member of an opposite-sex friendship demanding a romantic relationship of the other.

In later review of the studies, the support or confirmation category was inserted into acts of devotion and included another category, uncharacteristic social behavior. These are acts that are not relational but are unexpected, such as a quiet person raising his or her voice.

In terms of the response to expectancy violations, the sensitivity of expectancy violations varies from genders. Research found that women are less tolerant than men when their expectation are violated by negative behaviors, regardless of the types of violations such as dishonesty and immorality.

Friendship

Expectations with friends formulate over time and are usually brought together by a series of observations of behavior and predictions on how that friend will act in the future. When these expectations are violated, it often can be damaging and dangerous for a close friendship. It can cause an end to the friendship and create a strong negative experience in that person's life. Over time, people might expect friends to act consistently around them until a violation to this expectation takes place. For example, when they begin "breaking promises or even acting in an inauthentic manner to impress others, can have aversive consequences for close relationships" (Cohen 2010). People expect their friends to act in a social manner and adhere to all of our personal rules they set in their minds, such as being nice, kind, considerate, and refraining from any comment that puts another down. This is a part of the personal rules with a personal friendship, though in a different setting with that individual around different people, the rules may be broken. While this might be an offense in one's eyes, it may not be offensive in the others. Each negative experience can deteriorate the relationship and allow more experiences where expectations are continually violated until the relationship is dissolved. Cohen said "the more that a friendship is voluntary, easily replaceable, and disconnected from external pressures to continue, the more vulnerable it is to expectancy violation damage" (Cohen, 2010). Someone will always look for the better option if a negative experience has taken place. The more invested someone is in a friendship, the stronger the effect will have on the individual when expectations are violated.

Gender also plays a role in expectancy violation. Friendships with members of the same sex usually operate differently than those between different sexes. Women are generally less tolerant with men when violations have taken place. Relationships, whether it be with the same sex or not, tend to fail over time when one or both parties do not adhere the norms that the other is accustomed to and engage in behaviours such as hostile attitudes, sharp comments, distancing from the other, etc. Both parties are also capable of violating each other's expectations at the same time. It is not just one person in the relationship that perceives behavior as unusual. One can respond to a violation with another social violation, leaving the friendship in confusion of the direction it is going.

Family relationships: phubbing

Expectations in family relationships are prone to being violated via phubbing. Phubbing is a term coined to describe when an individual goes on their phone and mentally removes themselves from the conversation and physical reality, thus snubbing their interaction partners. This violates expectations in family relationships when a younger individual is around an older adult. Travis Kadylak found that "older adults feel ignored and disrespected" in situations where a younger family member is phubbing. In this case, the younger individually and unconsciously violated the older adult's expectations that stems from the adult's perception of social etiquette. Kadylak calls for further research on how phubbing expectancy violations affect the well-being of older adults.

When it comes to smartphone use in conversations overall, researchers found that proactive and reactive smartphone use, often use that interrupts the conversation, leaves to lower perceived attentiveness and politeness from the conversational partner due to their expectations of a direct conversation being violated. Whereas integrative smartphone use, when the smartphone becomes a part of the conversation, leaves no significant impact on the perception of the conversation.

Romantic relationships

Expectancy violations happen frequently in romantic relationships. In relationships there is an unspoken expectation when interacting and that is the significant other will give their full undivided attention when in the presence of their significant other. As the new generation evolves, the face to face contact has changed. With the access use of phones and social media the attention of individuals has shifted to their devices and continues to become worse. Since there is access to many mobile devices, there has been an increase of lack of communication face to face. This has made it difficult for some relationships to grow and has created conflict because the expectation of attention has been shifted. "Individuals expect conversational partners to be moderately involved in an interaction (Burgoon, Newton, Walther, & Baesler, 1989). Within existing relationships, partners rely on one another to show interest and immediacy in interactions (White, 2008). However, the presence of cell phones and the expectation to be constantly available (Ling, 2012) impacts partners' abilities to give full attention to one another" (Miller-Ott, A., & Kelly, L. 2015).

Regardless of where the romantic relationship takes place, people are likely to have negative valence about cell phone usage, including texting, viewing news and playing games, if their expectations of attention and intimacy are violated. In addition, excessive cell phone usage during a date has a great impact on romantic partner's negative valence towards the usage. However, Miller-Ott and Kelly found that a small amount of cell phone usage during a date is acceptable, such as responding to a text message and quickly bringing attention back to the date partner. The same behavior in different occasions and contexts is viewed differently in terms of the degree of valence. Research found that same behavior is viewed as more negative in a restaurant than at home. Since people are more likely to have higher expectations for undivided attention during formal contexts, using a cell phone in formal dates will more negatively violate partner's expectations. Divided attention is acceptable in casual contexts – therefore, the degree of expectancy violations is low under a hanging out context.

After expectation are violated in the romantic relationships, one may assume that an apology may fix expectations that were violated; however, Benjamin W Chiles and Michael E. Roloff found that "apology is positively evaluated by apologizers, this relationship is moderated by their expectations of acceptance prior to the actual response to the apology". Laura K. Guerrero and Guy F. Bachman found that high quality relationships tend to forgive more than relationships with less investments, yet they tend to inflict hurt intentionally.

In a study done in 2022, Lilly and Buehler conducted a survey measuring young adults' reaction to sexually explicit introductions on an online dating tool versus a traditional introduction. They found that young adults were much more likely to negatively react to a sexually explicit introduction as opposed to a traditionally one. The study discusses how EVT is the main cause of this negative reaction. Because the receiver is expecting a traditional introduction as opposed to a sexually explicit one, the receiver's expectations are violated and they experience a negative reaction. Lilly and Buehler recommend while using an online dating tool to wait to send a sexually explicit message until it follows potential expectations if at all. Following expectations can be critical for online dating even in a more minute sense. DelGreco and Denes found when it comes to a woman receiving a compliment from a man using an online dating tool, her response can leave a lasting impact if it violates expectations. The study found that men expect women to be thankful for the compliment. If the woman negatively violates expectations with agreement or self praise, there tends to be the biggest negative impact left on the man. If the woman positively violates expectations with denial or disagreement, there is still a significant negative impact left on the man. Ultimately, EVT and gender roles/expectations can be very applicable to one another.

Cell phone usage

Cell phone usage behaviors that do not contradict intimate moment are viewed as positive violations, including sharing interesting messages and playing online games together. People have less negative valence on cell phone usage if they gain more reward from the behaviors.

Research also found the most common response to the violated cell phone usage is to do nothing. However, people have different reactions to the violations under different stages of romantic relationships. In the early stage of dating, people are more likely to respond by indirect messages and silence. While there are direct verbal responses when expectations are violated in established relationships.

Sexual resistance

Sexual resistance is viewed as a typical expectancy violation in romantic relationships. In 2003, Bevan used EVT to evaluate the impact of sexual resistance on close relationships. The research focused on two considerations: relational contexts and directness of the messages.

The research concluded that people who are resisted in a romantic relationship perceived the violation of sexual resistance as more negative and unexpected than those resisted in a regular cross-sex friendship. The reason might because romantic partners believe that they have clearer and deeper understanding of each other's expectations and degree of acceptance and tolerance. When it comes to message directness of sexual resistance, although the study did not find any significant difference of levels of violation valence and expectedness between direct and indirect messages, direct sexual resistance messages in close relationships proved to be more relationally important than indirect messages. Therefore, direct sexual resistance messages will be a harmful factor that affects the continuity of a romantic relationship.

Hurtful events

The degree of expectancy violations in romantic relationships quality affect how partners react to hurtful events caused by their partner. Partners who view their significant others as positively rewarding are more keen to use constructive communication after experiencing a negative hurtful event. EVT analysis approach also show that if the negative valence happens when partners find the other to be unrewarding, it results in destructive communication, leading to breakups.

Online dating

Maria DelGreco and Amanda Denes investigate men and women's expectations and interpretations of communicative cues in the initiation stage of heterosexual online dating. When women expect men's responses to compliment, women face negative deviation when men express narcissism and agreement. Moreover, women with positive deviations of expectations are assessed more negatively than those who align with expectations.

Computer-mediated communication and social media

As has previously been addressed, EVT has evolved tremendously over the years, expanding beyond its original induction when it focused on FtF communication and proxemics. The advancement of information and communications technology has provided tools for expressing oneself and conveying messages beyond just typing in text. As already discussed, arousal can divert one's attention or interest from a message to the source of the arousal. Virtual realities created online through computer-mediated communication (CMC), especially those which evoke strong visual presence through media, can increase arousal levels, such as those with high violent or sexual content. Just as people may use television viewing to increase or decrease arousal levels, people may use media in online communication to increase or decrease arousal levels. People may interact with others online by assuming the identities of avatars which may take on completely different, alternate personalities. The differences in perceived intimateness, co-presence, and emotionally-based trust can very significantly between avatar communication and other communication modalities such as text chat, audio, and audio-visual. The media options available to users when communicating with others online present a host of potential expectancy violations unique to CMC.

The introduction of social media networks such as Facebook and Twitter, as well as dating social networks such as Match.com and eHarmony, has greatly contributed to the increased use of computer-mediated communication which now offers a context for studying communication devoid of nonverbal information. Though these media are relatively new, they have been in existence long enough for users to have developed norms and expectations about appropriate behaviors in the online world. However, there has been a lag by researchers to study and understand these new established norms, which makes CMC rich with heuristic possibilities from a communications theory perspective.

Ramirez and Wang studied the occurrence and timing of modality switching, or shifts from online communication to FtF interaction, from the perspective of EVT. Their research documented inconsistent findings which revealed in some instances relationships were enhanced and in others they were dampened, indicating the expectations, evaluations, and outcomes associated with initial modality switches varied amongst individuals. Additionally, studies have found that when individuals who meet online meet face-to-face for the first time, the length of time spent communicating online can determine whether individuals will rate physical characteristics of each other positively or negatively. Unlike FtF communication, CMC allows people to pretend to be connected with a person who violates their expectancy by ignoring violations or filtering news feed. Meanwhile, people can also cut the connection completely with someone who is not important by deleting friendship status when a serious violation occurs. A confrontation is much more likely for close friends than for acquaintances, and compensation is much more likely for acquaintances, a finding which contrasts typical EVT predictions. Furthermore, EVT on the Internet environment is strongly related to online privacy issues.

In a study done in 2018, Tang found that expectation violations of both the amount of likes a post gets, and the expectation violating of who likes the post, can negatively affect the original poster's mental health and perceived friend support.

Online Activism Judgments

In a study measuring the effects of third party expectations and judgements when viewing anti-Asian hate tweets, Tong and DeAndrea found how powerful expectancies can be. In the experiment, Tong and DeAndrea took 196 white active X users and measured their political ideologies on a scale from 1 (a strong republican) to 7 (a strong democrat). Then the researchers showed each participant an extremely offensive fake anti-Asian post on the platform from either a white or black poster indicated by the profile picture. Then they asked the participants a serious of questions. Tong and DeAndrea found that white republicans viewed a black poster spreading anti-Asian hate as more ethnically prototypical compared to a white poster. On the contrary, white democrats viewed a white posters spreading anti-Asian hate as more ethnically prototypical compared to a black poster. Additionally, the stronger the republican, the stronger they viewed the black poster as ethnically prototypical. The stronger the democrat, the stronger they viewed the white person as ethnically prototypical. Moderates consistently fell in the middle.

In social media, such as Facebook, people are connected online with friends and sometimes strangers. Norm violations on Facebook may include too many status updates, overly emotional status updates or Wall posts, heated interactions, name calling through Facebook's public features, and tags on posts or pictures that might reflect negatively on an individual. Research indicates that the perception of this act as a negative expectancy violation is influenced by factors such as the duration of the Facebook friendship and the nature of the personal ties between the individuals involved. Longer-standing Facebook friendships, as well as stronger personal connections, tend to result in the unfriending action being viewed as a more significant breach of social norms and expectations. This severity, in turn, plays a role in whether the individual who initiates the unfriending communicates their decision to the other party. The research highlights the intricate dynamics of online social interactions and the weighted considerations behind the decision to unfriend, reflecting the nuanced nature of digital relationships and the expectations that govern them.

In a study conducted by Fife, Nelson, and Bayles of focus groups from a Southeastern liberal arts university, five themes were ascertained regarding Facebook use and expectancy violations:

- ""Don't stalk' – and when you do, don't talk about it"

- Though an understanding exists among Facebook participants that users will use the site to keep track of the behavior of others in a number of ways, excessive monitoring is likely to be perceived as an expectancy violation.

- "Don't embarrass me with bad pictures"

- Users may have the ability to control which pictures they post on their own Facebook page, but they do not have the ability to control what others post. Posting and "tagging" unflattering pictures of others may create expectancy violations.

- "Don't mess up my profile"

- Several participants expressed annoyance of others who alter their profiles knowing that their alterations could be perceived negatively, though they did not mention changing their passwords or protecting themselves in other ways.

- "Choose an appropriate forum for messages"

- Messages can be sent between Facebook participants through 'Facebook messages', which are not public, or 'wall postings', which can be viewed by anyone specified in the user's privacy controls. Posting messages which may be perceived as private, embarrassing, or inappropriate to a wall posting can create expectancy violations.

- "Don't compete over number of friends"

- Facebook users maintain a running total of 'friends' on their profile which is viewable to others. Engaging in comparisons with others over this statistic can create expectancy violations.

In 2010, Stutzman and Kramer-Duffield examined college undergraduates' motivations to have friends-only profiles on Facebook. Having a friends-only profile is a practical method to enhance privacy management on Facebook. The two authors made distinctions between intended audience, to whom one hopes to disclose the Facebook profile, and expected audience, a group of people by whom one thinks the Facebook profile has been viewed. The study indicated that "expectancy violations were identified as instances where an expected audience was not jointly identified as an intended audience". Facebook networks were categorized into different levels: strong ties of family and intimate friends, weak ties comprising "casual friends and campus acquaintances", and outsiders such as "faculty or administrators". According to the study, expectancy violations by weak ties showed greater relevance to the establishment of a friends-only profile among college undergraduates, compared to other Facebook network ties.

Electronic mail

Email has become one of the most widely used methods of communication within organizations and workplaces. When discussing expectancy violations with electronic e-mail, just as with other modes of communication, a distinction must be made between inadvertent violations of norms and purposeful violations, referred to as 'flaming'. Flaming is defined as hostile and aggressive interactions via text-based CMC.

One form of expectancy violation in email is the length of time between the sending of the initial email and the receiver's reply. Communicator reward valence plays a large part in how expectancy violations are handled in email communications. In computer-mediated communication, people have expectations to others' online behaviors based on individual identity. In online contexts, violations are not simply assessed as positive or negative. Some violations are ambiguous such as e-mail response latency. In 2017, Nicholls and Rice stated that "when deviation is ambiguous, the communicator's reward value will mediate the perceptions of the deviation."

Chronemic studies on email have shown that in organizations, responder status played a large part in how individuals reacted to various lapses in response to the previously sent email. Long pauses between responses for high-status responders produced positive expectancy violation valence and long pauses from low-status responders produced a negative expectancy violation valence. However, in the case of job interviews, long pauses between email for high-status candidates reflected negatively on their reviews. Expectations for email recipients to respond within a normative time limit illustrate the medium's capacity for expectancy violations to occur.

Academic environment

Teacher anger

McPherson, Kearney, and Plax examined teacher anger in college classrooms through the lens of norm violations. Naturally, teachers will become frustrated and angry with students in classrooms from time to time. How teachers express themselves and convey those emotions will determine how students respond and interpret those emotional demonstrations. The students judged the appropriateness of teachers' anger in classrooms in the modal expressions of distributive aggression, passive aggression, integrative assertion, and nonassertive denial. Students rated the aggressive expressions as highly intense, destructive, and inappropriate (or non-normative), including such behaviors as sarcasm or putdowns (most frequently cited), verbal abuse, rude and condescending behaviors toward students, and acts intended to demoralize students. The students described assertive displays as appropriate and less intense. Although anger is often considered to be a negative emotion, teacher anger is not necessarily a violation of classroom norms. Based on the study, intense and aggressive displays of teacher anger are considered socially inappropriate by students. These perceived norm violations result in negative evaluations of the teacher and the course. Because only integrative-assertive expressions of teacher anger were positively related to students' perceptions of appropriateness, the study concluded that teachers should avoid intense, aggressive anger displays and should rather assertively and directly discuss the problem with students.

Teacher dress

Clothing is considered a form of nonverbal communication. Dress communicates status, hierarchy, credibility, and attractiveness. Specific social codes dictate what forms of dress are appropriate in various cross-cultural contexts. When individuals wear clothing that is deemed inappropriate for a given situation, or when an individual's clothing does not seem to match their perceived status or attractiveness, this can constitute an expectancy violation. Studies on clothing and teacher perceptions have shown that when teachers wear formal attire, students rate their credibility higher. However, for high-reward teachers, clothing formality did not raise perceptions of attractiveness.

In educational contexts

EVT posits that deviations from expected behavior can influence social judgments. In the context of teacher dress, formal attire aligns with expectations of a teacher's role, and such congruence typically results in favorable credibility assessments. The impact of clothing on expectations, where attire considered appropriate to the teaching context bolstered perceptions of a teacher's potential for student academic success.

A mixed method study conducted in 2023 followed first generation college students and their social expectations for their transition to college. Overall students reported negative violations when it came to partying, making new friends, and strengthening new bonds. They also experienced positive violations when it came to stress and workload. Students who reported more negative violations also reported an overall more difficult transition period. Students who reported more positive violations reported an easier transition period.

Implications for teacher dress code

The implications of these studies are twofold: they reaffirm the importance of attire as a component of nonverbal communication within educational settings, and they highlight the potential for teacher attire to align with institutional norms and expectations to enhance educational outcomes. While the preference for formality in attire may vary by educational context, the consensus points to the benefit of teachers adopting attire that reflects the scholastic values and expectations of their specific academic environments.

Instructor credibility in college classroom

According to Sidelinger and Bolen, students might be dissatisfied with instructors who talk a lot during class. After researching compulsive communication and communication satisfaction, they concluded that if an instructor is evaluated as credible by the students, his credibility decreases students' dissatisfaction despite his talkativeness. Particularly, instructor's goodwill, such as politeness and care for students, is the most effective characteristic to alleviate students' negative feelings towards them (the talkative instructor).

Expanding on this, EVT suggests that communication behaviors deviating from expectations can be perceived as either positive or negative violations. When an instructor's behavior, like excessive talking, contrasts with student expectations of a participatory, student-centered environment, it constitutes an expectancy violation. However, the impact of such a violation hinges on the perceived credibility of the instructor. Instructor credibility, shaped by expertise, trustworthiness, and goodwill, can act as a buffer against the negative effects of such expectancy violations. Goodwill, in particular, plays a crucial role. When students perceive an instructor as genuinely concerned about their learning and well-being, they are more likely to overlook behaviors otherwise considered negative. This is because EVT emphasizes the relationship's nature over the behavior itself in determining the outcome of expectancy violations. Furthermore, cultural differences among students, the discipline, course level, and class dynamics can influence the context and perception of expectancy violations. Future research could explore how different expectancy violations (like talkativeness, humor, strictness) interact with dimensions of instructor credibility and how cultural factors among students shape their expectations and perceptions of instructor behavior. This would provide a deeper understanding of how instructor behaviors affect student satisfaction and learning outcomes in diverse educational environments.

Course ratings

Most American colleges and universities employ course rating surveys as a method to gauge teacher effectiveness and the degree to which students are satisfied with the pedagogy of their professors. Expectancy violation and violation valence play a part in course ratings because a wide range of expectancies exist for students while taking a course. Common expectancies for students include stimulation and interest, instructor behavior, relevance of the course, and the student's expected and actual success in the course. A higher education study on EVT and course ratings analyzed 228 students in seven introductory sociology classes at a university of 25,000 students. Since the courses were required for most students, were open to all students, used the same textbook, and met for the same length of time during the semester, expectancy violations in the classroom could be reported more accurately. Some factors used to report the data included instructor personality, interestingness and informativeness of textbook materials, difficulty of lectures, lecturer speaking ability, and the ability to answer questions. At the end of the study, the only factor that affected course ratings was relevance. Expectancies had virtually no effect otherwise on course evaluations. This reason could be attributed to the fact that students who found a course highly relevant were already interested in the subject area and were more motivated to do well. Additionally, professors who respond to student emails quicker than the students expect, tend to receive a better course evaluation rating than if they reply slower than expected.

Nontraditional college students

EVT has been used to study the experiences of non-traditional college and university students who begin an undergraduate education over the age of 25. The study focused on the students' expectations of their professors and how they should behave in the classroom. Since nontraditional students often feel that they are different from their academic peers, and since the traditional university setting focuses on the 18–23-year-old demographic, studying nontraditional student classroom experiences can help higher education institutions instruct teachers on how to behave in the classroom. Traditional and non-traditional students have been shown to expect teachers to make use of examples, provide feedback, and adequately prepare them for exams. Both traditional and non-traditional students have been found to have their expectations for instructor clarity negatively violated. Surprisingly, non-traditional students differed from traditional students by responding negatively to affinity-seeking behaviors and believed that instructors should be less concerned with making class more fun and enjoyable.

Student disclosures in college classroom

In 2013, Frisby and Sidelinger conducted a research about student disclosures in college classroom to examine what kinds of student disclosures would violate peers' expectations and their perceptions about the disclosers. According to the study, those who make inappropriate disclosures violate others' expectations most in a classroom environment. Inappropriate disclosures are described as high frequent, negative, offensive and irrelevant topics. Disclosers of inappropriate information are more likely to be described as incompetent students, and they are less likeable than students who disclose appropriate information that are related to course materials.

Students' expectations towards instructors in online classes

Taking EVT as a lens, Renee Bourdeaux and Lindsie Schoenack investigate students' reasons for taking online classes, their expectations towards instructors, and the derivation of expectations of instructors' behaviors. Research shows that students expect clarity, respect, and well-designed course accommodating to the online environment. Participants consider effective communication and improving learning as behaviors bringing positive results. However, unprofessional behaviors, such as lack of use of teaching tools decreasing the productivity of classes, lead to negative results.

Business communication crisis

EVT can also apply to everyday business interaction between long-term partners, new partners, and even the consumers. Each time a business interacts with another, both sides expect a positive gain in some capacity; however, losses are inevitable. Sora Kim asserts that "expectancy violations caused by a crisis tend to increase uncertainty about an organization's performance in the crisis-related area". The author states that stakeholders, in the case of the BP Oil spill, held high levels of uncertainty towards the organization due to the high level of expectancy violations committed by BP. Sabrina Helm and Julia Tolsdorf found that firms with greater reputation and customer loyalty are set to high expectations by the public, and tend to suffer more loss in profits in the event of a crisis, while firms with low reputations suffer minor losses. This shows that the public places its trust and loyalty in corporations due to their reputation, thus resulting in favorable outcomes for corporations. This reputation is also an Achilles heel for the corporation in times of crisis because when an expectation violation is committed by the corporations it produces negative outcomes for the corporation and the public's trust in them. Sora Kim also exposes similar findings in her study, specifically on how expectations violations produces uncertainties in stakeholders and the public during times of crisis. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is an expectation the public has set for major corporations and businesses, Nick Lin-Hi and Igor Blumberg also found that not practicing CSR negatively affect corporate reputation.

YJ Sohn and Ruthann Lariscy use EVT to investigate the role corporate reputation plays in crisis situations and how the crisis affects the reputation valence, especially in a CSR (corporate social responsibility) crisis context. The previous high reputation leads to higher expectations for the corporation, which results in more detailed investigations of the expectation violation behaviors.

In a study done surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic, Cheng, Wang, and Pan studied that employees whose expectations about their work and the company were violated with a negative valence. They found that these negative violations created uncertainty, CSR cynicism, and distrust in their employing company, which ultimately led to an increase in company turnover rate.

In a study done in 2022, research was done concerning biases Black employees experience in the workplace. Self promotion by Black employees was considered to be related to poorer job performance and lower job fit ratings as compared to their white, Hispanic, and Asian counterparts. This can be attributed to EVT because self promotion by Black employees violates other races' expectations of themselves. Because the expectation is negatively violated, the Black employee promoting themselves now carry a negative association.

Profanity use

Swearing is one example of observable instance of verbal expectancy violations. Examples of swearing expectancy violations include U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney telling Patrick Leahy, Senator of Vermont, to "go fuck yourself", actor Christian Bale lashing out toward a crew member who walked in front of the camera while he was filming, and U.S. Vice President Joe Biden's remarks during a live broadcast of his speech congratulating U.S. President Barack Obama on passage of the health care reform bill, commenting that it was a "big fucking deal". Expletives also vary among different cultures, so valence of expectancy violations involving swearing may differ when used in different contexts.

In workplaces

Swearing is common among many workplaces. Swearing has been identified functionally as one of several ways to express emotion in response to workplace stress, to convey verbal aggression, or to engage in deviant workplace behavior (Johnson, 2012). In formal work settings, people have much stronger feelings that their expectations are violated by swearing than in casual occasions. Expletives are more prevalent in unstructured conversations than in more structured, task-oriented ones (Johnson, 2012). The use of profanity has been shown to influence the perceptions of speakers. It may also have emotional impact on the user and the audience. Research has shown that profanity users appear less trustworthy, less sociable, and less educated. The more swearing messages one expresses that violate respondent's expectations in workplaces, the more negative evaluations the respondent will generate about the speaker's incompetency. These traits are likely to appear as fixed among profanity users. Moreover, the content of the swearing messages also poses great impact on the extent of expectancy violations in formal work settings. The verbal messages include words related to sex, excretion and profaneness. Research found that respondents experience highest level of surprise about the swearing with sexual expressions. Thus their expectations are more likely to be violated by sexual swearing than excretory and profane words. A more productive approach than focusing on whether a specific word is offensive may be to make sure that those engaging in workplace swearing are aware of how they and their messages might be perceived in multiple ways (Johnson, 2012).

Evaluation of media figures

Expectancy violations are tightly related to the changes of people's evaluation on their relationships with media figures. In 2010, Cohen made comparisons between relationships with friends and media figures in order to find similarities and differences of people's reactions when their expectations are violated in these two relationships. Violations were generally divided in three categories: social violations such as making offensive comments, trust violations such as making up stories about their life experience, and moral violations such as cheating in a marital relationship or drunk driving.

Research indicated that in both friendships and relationships with media figures, social and trust violations are more offensive than moral violations. Specifically, people are more intolerable about moral violations from media figures than from their friends. According to the study, the reason for the intolerance is because relationships with media figures are relatively weak that people invest less on the relationships with media figures than on friendships. The type of media figures is also an important factor to determine the changes of closeness with media figures. People have different expectations to various types of media figures. Research discussed that moral violations negatively influence relationships with athletes, damaging their positive and energetic appearance expected by the public. Social violations reduce closeness with TV hosts, whom people expect as amiable public figures.

James Bonus, Nicholas Matthews, and Tim Wulf investigate adults' expectations towards movie characters before and after movie releasing. The result shows that when the villain behaves more morally than expected, there is a warming in the parasocial relationship between participants and villains. However, when conforming to moral expectations, there is no weakening in the parasocial relationship between heroes and participants.

Health and self-improvement

Expectancy violation theory has even been applied to encouraging healthy habits and changing bad ones. In a study by Karolien van den Akker, Myrr van den Broek, Remco C. Havermans, and Anita Jansen, expectancy violation theory was tested to see if it was successful in changing ingrained cravings for chocolate. Although researchers did not find that expectancy violation mediated responses to chocolate cravings, they believe more research is needed to determine whether this theory is profitable for this kind of application to human behavior.

Career development and job searching

Stephanie Smith examines how recent college graduates react to expectation violations in job searching and career development through communication. Smith finds that recent college graduates employ a package of both traditional and online social networking job searching strategies. As graduates expect job searching would be difficult, they are still surprised by the required intensity and effort. Through the lens of EVT, candidates with the most realistic goals and expectations received better results during the recruitment season. EVT also helps to understand candidates' interactions with contacts with potential rewards during the networking conversation. Also, a thank-you letter is regarded as a positive deviation from expectations because it reduces uncertainty.

Expectations of adults with autism

Expectancy violations theory has been applied in studies to determine whether people judge adults with autism as violating their expectations since people with autism can exhibit little-to-no eye contact, or facial expression, not recognize certain nonverbal cues, or utilize tones that neurotypicals may perceive as abnormal. In one manuscript replying to another study, Bishop describes communication deficits in autistic individuals as potentially violating one's expectations for social communication, thus being a form of expectation violation since people with autism can struggle with social communication. One study by Lim, Young, and Brewer hypothesized that people can incorrectly perceive autistic adults as having no credibility or being deceptive. They believed that due to expectancy violations theory, people will judge those who violate their expectations unfavorably in a negative light. They recorded videos of autistic and neurotypical adults attempting to persuade the interviewer that they did not steal an envelope of money and the participants of the study were to judge whether they believed the individuals in the interview were lying or telling the truth. The results showed that the autistic people were perceived as deceptive and less credible than the neurotypicals in the videos. These findings supported the hypothesis that autistic adults can violate expectations through certain behaviors or through other's knowledge of their diagnosis. A similar study by the same researchers, also conducted through interviews, showed that the behaviors of autistic adults can affect their perceived credibility. Another study by Logos, Brewer, and Young sought to determine the effect of EVT in a court setting. Their goal was to determine whether EVT could be applied to autistic adults in a forensic setting, using autistic and non-autistic "defendants", hypothesizing that the results would show that autistic adults would be judged guilty due to violations. Results showed that their hypothesis was correct, despite evidence indicating innocence.

Metatheoretical assumptions

Ontological assumptions

EVT assumes that humans have a certain degree of free will. This theory assumes that humans can assess and interpret the relationship and liking between themselves and their conversational partner, and then make a decision whether or not to violate the expectations of the other person. The theory holds that this decision depends on what outcome they would like to achieve. This assumption is based on the interaction position. The interaction position is based on a person's initial stance toward an interaction as determined by a blend of personal Requirements, Expectations, and Desires (RED). These RED factors meld into a person's interaction position of what is needed, anticipated, and preferred.

Epistemological assumptions

EVT assumes that there are norms for all communication activities and if these norms are violated, there will be specific, predictable outcomes. EVT does not fully account for the overwhelming prevalence of reciprocity that has been found in interpersonal interactions. Secondly, it is silent on whether communicator valence supersedes behavior valence or vice versa when the two are incongruent, such as when a disliked partner engages in a positive violation.

Axiological assumptions

This theory seeks to be value-neutral as supporting studies have been conducted empirically and sought to objectively describe how humans react when their expectations are violated.

Critique

Predictability and testability

EVT has undergone scrutiny for its attempt to provide a covering law for certain aspects of interpersonal communication. Some critics of EVT believe most interactions between individuals are extremely complex and there are many contingencies to consider within the theory. This makes the prediction of behavioral outcomes of a particular situation virtually impossible to consistently predict.

Another critique of the theory is the assumption that expectancy violations are mostly highly consequential acts, negative in nature, and cause uncertainty to increase between communicators. In actuality, research shows expectancy violations vary in frequency, seriousness, and valence. While it is true that many expectancy violations carry a negative valence, numerous are positive and actually reduce uncertainty because they provide additional information within the parameters of the particular relationship, context, and communicators.

A First Look at Communication

Emory Griffin, the author of A First Look at Communication Theory, analyzed unpredictability in EVT. His test consisted in analyzing his interaction with four students who made various requests from him. The students were given the pseudonyms Andre, Belinda, Charlie and Dawn. They start with the letters A, B, C and D to represent the increasing distance between them and Griffin when making their requests.

Andre needed the author's endorsement for a graduate scholarship, and spoke to him from an intimate eyeball-to-eyeball distance. According to Burgoon's early model, Andre made a mistake when he crossed Griffin's threat threshold; the physical and psychological discomfort the lecturer might feel could have hurt his cause. However, later that day Griffin wrote the letter of recommendation.

Belinda needed help with a term paper for a class with another professor, and asked for it from a 2-foot distance. Just as Burgoon predicted, the narrow gap between Belinda and Griffin determined him to focus his attention on their rocky relationship, and her request was declined.

Charlie invited his lecturer to play water polo with other students, and he made the invitation from the right distance of 7 feet, just outside the range of interaction Griffin anticipated. However, his invitation was declined.

Dawn launched an invitation to Griffin to eat lunch together the next day, and she did this from across the room. According to the nonverbal expectancy violations model, launching an invitation from across the room would guarantee a poor response, but this time, the invitation was successful.

Griffin's attempt to apply Burgoon's original model to conversational distance between him and his students did not meet with much success. The theoretical scoreboard read:

- Nonverbal expectancy violations model: 1

- Unpredicted random behavior: 3

However, when Griffin applied the revised EVT standards on his responses to "the proxemic violations of Andre, Belinda, Charlie, and Dawn," the scorecard "shows four hits and no misses."

Related theories

Because EVT is sociopsychological in nature and focuses on social codes in both intrapersonal and interpersonal communication, it is closely related to communication theories such as cognitive dissonance and uncertainty reduction theory. Recently, this theory has undergone some reconstitution by Burgoon and her colleagues and has resulted in a newly proposed theory known as interaction adaptation theory, which is a more comprehensive explanation of adaptation in interpersonal interaction.

As mentioned above, EVT has strong roots in uncertainty reduction theory. The relationship between violation behavior and the level of uncertainty is under study. Research indicates that violations differ in their impact on uncertainty. To be more specific, incongruent negative violations heightened uncertainty, whereas congruent violations (both positive and negative) caused declines in uncertainty. The theory also borrows from social exchange theory in that people seek reward out of interaction with others.

Two other theories share similar outlooks to EVT – discrepancy-arousal theory (DAT) and Patterson's social facilitation model (SFM). Like EVT, DAT explains that a receiver becomes aroused when a communicative behavior does not match the receiver's expectations. In DAT, these differences are called discrepancies instead of expectancy violations. Cognitive dissonance and EVT both try to explain why and how people react to unexpected information and adjust themselves during communication process.

The social facilitation model has a similar outlook and labels these differences as unstable changes. A key difference between the theories lies in the receiver's arousal level. Both DAT and SFM maintain that the receiver experiences a physiological response whereas EVT focuses on the attention shift of the receiver. EVT posits that expectancy violations occur frequently and are not always as serious as perceived through the lenses of other theories.

Anxiety/uncertainty management theory is the uncertainty and anxiety people have towards each other, relating to EVT this anxiety and uncertainty can differ between cultures. Causing a violation for example violating someones personal distance or communicating ineffectively can cause uncertainty and anxiety.

The popularity of computer-mediated communication (CMC) as means of conducting task-oriented and socially oriented interactions is a part of the social information processing (SIP) theory. Coined by Joseph Walther, the theory explores CMC's ability to fulfill many of the same functions as the more traditional forms of interaction, especially face-to-face (FtF) interaction. SIP can be used in conjunction with EVT to examine interpersonal and hyperpersonal relationships established through CMC.

Further use and development of the theory

The concept of social norms marketing follows expectancy violation in that it is based upon the notion that messages containing facts that vary from perception of the norm will create a positive expectancy violation. Advertising, strategic communications, and public relations base social norms campaigns on this position.

Interaction adaptation theory further explores expectancy violations. Developed by Burgoon to take a more comprehensive look at social interaction, IAT posits that people enter into interactions with requirements, expectations, and desires. These factors influence both the initial behavior as well as the response behavior. When faced with behavior that meets an individual's needs, expectations, or desires, the response behavior will be positive. When faced with behavior that does not meet an individual's needs, expectations, or desires, he or she can respond either positively or negatively depending on the degree of violation and positive or negative valence of the relationship.

Expectancies exert significant influence on people's interaction patterns, on their impressions of one another, and on the outcomes of their interactions. People who can assume that they are well regarded by their audience are safer engaging in violations and more likely to profit from doing so than are those who are poorly regarded. When the violation act is one that is likely to be ambiguous in its meaning or to carry multiple interpretations that are not uniformly positive or negative, then the reward valence of the communicator can be especially significant in moderating interpretations, evaluations, and subsequent outcomes.

EVT also applies to international experience in the workplace. "A foreign newcomer who has the necessary education, work experience, and international experience will be perceived as having the ability to make valuable contribution to the group's task. Consequently, education, work experience and international experience will influence a foreign newcomer's initial task-based group acceptance" (Joardar, 2011). It can be argued that a person with significant international experience will be perceived as having had the opportunity to learn how to build valuable relationships in a cross-cultural setting. Hence, international experience will have effects on initial relationship-based group acceptance as well. Meaning, this will make for a more positive expectancy violation, in the workplace especially. EVT is also used as a framework to analyze the negative impact of mind reading expectations on romantic relationships. In 2015, Wright and Roloff explain the idea of mind reading expectations (MRE) that romantic partners should clearly know about each other's feelings even though they are not being informed. When relational partners have done something wrong without self-consciousness, people's expectations are violated. Particularly those who hold high value of MRE are more likely to become distressful once their relational partners are unaware of their violations to expectations. The study asserts that such kinds of violations related to MRE result in responses such as combative attitude and silent treatment, which is harmful to long-term romantic relationships.

See also

References

- ^ Burgoon, J.K.; Hale, J.L. (1988). "Nonverbal Expectancy Violations: Model Elaboration and Application to Immediacy Behaviors". Communication Monographs. 55: 58–79. doi:10.1080/03637758809376158.

- ^ Burgoon, J.K.; Jones, S.B. (1976). "Toward a Theory of Personal Space Expectations and their Violations". Human Communication Research. 2 (2): 131–146. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1976.tb00706.x.

- ^ Burgoon, J. K. (1978). "A Communication Model of Personal Space Violations: Explication and an Initial Test". Human Communication Research. 4 (2): 130–131. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1978.tb00603.x. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- Burgoon, Judee (1992). Applying a comparative approach to nonverbal expectancy violations theory. Sage. pp. 53–69. In J. Blumler, K. E. Rosengren, & J. M. McLeod (Eds.), Comparatively speaking: Communication and culture across space and time (pp. 53–69). Newbury Park, CA: Sage

- Guerrero, L.K.; Bachman, G.F. (2008). "Relational quality and relationships: An expectancy violations analysis". Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 23 (6): 943–963. doi:10.1177/0265407506070476. S2CID 145377577.

- Burgoon, J.K. (1983). "Nonverbal Violations of Expectations". In J.M. Wiemann; R.R. Harrison (eds.). Nonverbal Interaction. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. pp. 11–77.

- Burgoon, J. K.; Jones, S. B. (1976). "Toward a Theory of Personal Space Expectations and Their Violations". Human Communication Research. 2 (2): 131–146. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1976.tb00706.x.

- Floyd, K.; Voloudakis, M. (1999). "Affectionate Behavior in Adult Platonic Friendships: Interpreting and Evaluating Expectancy Violations". Human Communication Research. 25 (3): 341–369. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1999.tb00449.x.

- ^ Griffin, Em (2011). "Chapter 7: Expectancy Violations Theory". A First Look at Communication Theory (8 ed.). The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. pp. 84–92. ISBN 978-0073534305.

- Snyder, Mark; Stukas, Arthur A. (1999). "Interpersonal Processes: The Interplay of Cognitive, Motivational, and Behavioral Activities in Social Interaction". Annual Review of Psychology. 50: 273–303. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.273. PMID 10074680. S2CID 8303839.

- McPherson, M. B.; Yuhua, J. L. (2007). "Students' Reactions to Teachers' Management of Compulsive Communicators". Communication Education. 56: 18–33. doi:10.1080/03634520601016178. S2CID 141659949.

- ^ M. L. Houser (2005). "Are We Violating Their Expectations? Instructor Communication Expectations of Traditional and Nontraditional Students". Communication Quarterly. 53 (2): 217–218. doi:10.1080/01463370500090332. S2CID 143959947.

- ^ Burgoon, J. K., & Hale, J. L. (1988). Nonverbal expectancy violations: Model elaboration and application to immediacy behaviors. Communications Monographs, 55(1), 58–79.

- ^ Burgoon, J. K.; S. B. Jones (1976). "Toward a Theory of Personal Space Expectations and Their Violations". Human Communication Research. 2 (2): 131–146. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1976.tb00706.x.

- Burgoon, Judee K.; Walther, Joseph B. (1990-12-01). "Nonverbal Expectancies and the Evaluative Consequences of Violations". Human Communication Research. 17 (2): 232–265. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1990.tb00232.x. ISSN 1468-2958.

- ^ L. K. Guerrero; P. A. Anderson; V. A. Afifi (2011). "Making Sense of Our World". Close Encounters: Communication in Relationships (3rd ed.). United States of America: Sage Publications, Inc. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-4129-7737-1.

- ^ Mehrabrian, A. (1981). Silent Messages. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Sebenius, James K. (2009), Assess, Don't Assume, Part I: Etiquette and National Culture in Negotiation, Harvard Business School Working Pape, No. 10-048, Harvard Business School

- ^ West, R. L.; L. H. Turner (2007). Introducing Communication Theory: Analysis and Application (3rd ed.). The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. p. 188. ISBN 9780073135618.

- Burgoon, J. K., ed. (2015). "Expectancy violations theory.". The international encyclopedia of interpersonal communication. pp. 1–9.

- Burgoon, Judee K.; Coker, Deborah A.; Coker, Ray A. (1986). "Communicative Effects of Gaze Behavior: A Test of Two Contrasting Explanations". Human Communication Research. 12 (4). Oxford University Press: 495–524. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1986.tb00089.x. ISSN 0360-3989.