| Facial trauma | |

|---|---|

| |

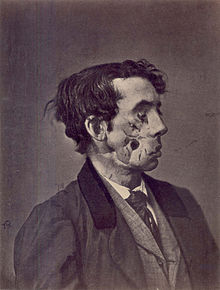

| 1865 illustration of a private injured in the American Civil War by a shell two years previously | |

| Specialty | Oral and maxillofacial surgery |

Facial trauma, also called maxillofacial trauma, is any physical trauma to the face. Facial trauma can involve soft tissue injuries such as burns, lacerations and bruises, or fractures of the facial bones such as nasal fractures and fractures of the jaw, as well as trauma such as eye injuries. Symptoms are specific to the type of injury; for example, fractures may involve pain, swelling, loss of function, or changes in the shape of facial structures.

Facial injuries have the potential to cause disfigurement and loss of function; for example, blindness or difficulty moving the jaw can result. Although it is seldom life-threatening, facial trauma can also be deadly, because it can cause severe bleeding or interference with the airway; thus a primary concern in treatment is ensuring that the airway is open and not threatened so that the patient can breathe. Depending on the type of facial injury, treatment may include bandaging and suturing of open wounds, administration of ice, antibiotics and pain killers, moving bones back into place, and surgery. When fractures are suspected, radiography is used for diagnosis. Treatment may also be necessary for other injuries such as traumatic brain injury, which commonly accompany severe facial trauma.

In developed countries, the leading cause of facial trauma used to be motor vehicle accidents, but this mechanism has been replaced by interpersonal violence; however auto accidents still predominate as the cause in developing countries and are still a major cause elsewhere. Thus prevention efforts include awareness campaigns to educate the public about safety measures such as seat belts and motorcycle helmets, and laws to prevent drunk and unsafe driving. Other causes of facial trauma include falls, industrial accidents, and sports injuries.

Signs and symptoms

Fractures of facial bones, like other fractures, may be associated with pain, bruising, and swelling of the surrounding tissues (such symptoms can occur in the absence of fractures as well). Fractures of the nose, base of the skull, or maxilla may be associated with profuse nosebleeds. Nasal fractures may be associated with deformity of the nose, as well as swelling and bruising. Deformity in the face, for example a sunken cheekbone or teeth which do not align properly, suggests the presence of fractures. Asymmetry can suggest facial fractures or damage to nerves. People with mandibular fractures often have pain and difficulty opening their mouths and may have numbness in the lip and chin. With Le Fort fractures, the midface may move relative to the rest of the face or skull.

Cause

Injury mechanisms such as falls, assaults, sports injuries, and vehicle crashes are common causes of facial trauma in children as well as adults. Blunt assaults, blows from fists or objects, are a common cause of facial injury. Facial trauma can also result from wartime injuries such as gunshots and blasts. Animal attacks and work-related injuries such as industrial accidents are other causes. Vehicular trauma is one of the leading causes of facial injuries. Trauma commonly occurs when the face strikes a part of the vehicle's interior, such as the steering wheel. In addition, airbags can cause corneal abrasions and lacerations (cuts) to the face when they deploy.

Diagnosis

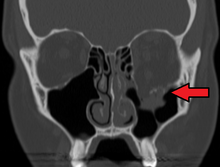

Radiography, imaging of tissues using X-rays, is used to rule out facial fractures. Angiography (X-rays taken of the inside of blood vessels) can be used to locate the source of bleeding. However the complex bones and tissues of the face can make it difficult to interpret plain radiographs; CT scanning is better for detecting fractures and examining soft tissues, and is often needed to determine whether surgery is necessary, but it is more expensive and difficult to obtain. CT scanning is usually considered to be more definitive and better at detecting facial injuries than X-ray. CT scanning is especially likely to be used in people with multiple injuries who need CT scans to assess for other injuries anyway.

Classification

|

|

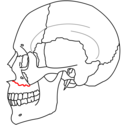

| Le Fort I fractures | |

|

|

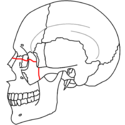

| Le Fort II fractures | |

|

|

| Le Fort III fractures | |

Soft tissue injuries include abrasions, lacerations, avulsions, bruises, burns and cold injuries.

Commonly injured facial bones include the nasal bone (the nose), the maxilla (the bone that forms the upper jaw), and the mandible (the lower jaw). The mandible may be fractured at its symphysis, body, angle, ramus, and condyle. The zygoma (cheekbone) and the frontal bone (forehead) are other sites for fractures. Fractures may also occur in the bones of the palate and those that come together to form the orbit of the eye.

At the beginning of the 20th century, René Le Fort mapped typical locations for facial fractures; these are now known as Le Fort I, II, and III fractures (right). Le Fort I fractures, also called Guérin or horizontal maxillary fractures, involve the maxilla, separating it from the palate. Le Fort II fractures, also called pyramidal fractures of the maxilla, cross the nasal bones and the orbital rim. Le Fort III fractures, also called craniofacial disjunction and transverse facial fractures, cross the front of the maxilla and involve the lacrimal bone, the lamina papyracea, and the orbital floor, and often involve the ethmoid bone, are the most serious. Le Fort fractures, which account for 10–20% of facial fractures, are often associated with other serious injuries. Le Fort made his classifications based on work with cadaver skulls, and the classification system has been criticized as imprecise and simplistic since most midface fractures involve a combination of Le Fort fractures. Although most facial fractures do not follow the patterns described by Le Fort precisely, the system is still used to categorize injuries.

Prevention

Measures to reduce facial trauma include laws enforcing seat belt use and public education to increase awareness about the importance of seat belts and motorcycle helmets. Efforts to reduce drunk driving are other preventative measures; changes to laws and their enforcement have been proposed, as well as changes to societal attitudes toward the activity. Information obtained from biomechanics studies can be used to design automobiles with a view toward preventing facial injuries. While seat belts reduce the number and severity of facial injuries that occur in crashes, airbags alone are not very effective at preventing the injuries. In sports, safety devices including helmets have been found to reduce the risk of severe facial injury. Additional attachments such as face guards may be added to sports helmets to prevent orofacial injury (injury to the mouth or face); mouth guards also used. In addition to factors listed above, correction of dental features that are associated with receiving more dental trauma also helps, such as increased overjet, Class II malocclusions, or correction of detofacal deformities with small mandible

Treatment

Woman with a prosthesis for facial trauma, 1900-1950

Woman with a prosthesis for facial trauma, 1900-1950

An immediate need in treatment is to ensure that the airway is open and not threatened (for example by tissues or foreign objects), because airway compromisation can occur rapidly and insidiously, and is potentially deadly. Material in the mouth that threatens the airway can be removed manually or using a suction tool for that purpose, and supplemental oxygen can be provided. Facial fractures that threaten to interfere with the airway can be reduced by moving the bones back into place; this both reduces bleeding and moves the bone out of the way of the airway. Tracheal intubation (inserting a tube into the airway to assist breathing) may be difficult or impossible due to swelling. Nasal intubation, inserting an endotracheal tube through the nose, may be contraindicated in the presence of facial trauma because if there is an undiscovered fracture at the base of the skull, the tube could be forced through it and into the brain. If facial injuries prevent orotracheal or nasotracheal intubation, a surgical airway can be placed to provide an adequate airway. Although cricothyrotomy and tracheostomy can secure an airway when other methods fail, they are used only as a last resort because of potential complications and the difficulty of the procedures.

A dressing can be placed over wounds to keep them clean and to facilitate healing, and antibiotics may be used in cases where infection is likely. People with contaminated wounds who have not been immunized against tetanus within five years may be given a tetanus vaccination. Lacerations may require stitches to stop bleeding and facilitate wound healing with as little scarring as possible. Although it is not common for bleeding from the maxillofacial region to be profuse enough to be life-threatening, it is still necessary to control such bleeding. Severe bleeding occurs as the result of facial trauma in 1–11% of patients, and the origin of this bleeding can be difficult to locate. Nasal packing can be used to control nose bleeds and hematomas that may form on the septum between the nostrils. Such hematomas need to be drained. Mild nasal fractures need nothing more than ice and pain killers, while breaks with severe deformities or associated lacerations may need further treatment, such as moving the bones back into alignment and antibiotic treatment.

Treatment aims to repair the face's natural bony architecture and to leave as little apparent trace of the injury as possible. Fractures may be repaired with metal plates and screws commonly made from Titanium. Resorbable materials are also available; these are biologically degraded and removed over time but there is no evidence supporting their use over conventional Titanium plates. Fractures may also be wired into place. Bone grafting is another option to repair the bone's architecture, to fill out missing sections, and to provide structural support. Medical literature suggests that early repair of facial injuries, within hours or days, results in better outcomes for function and appearance.

Surgical specialists who commonly treat specific aspects of facial trauma are oral and maxillofacial surgeons, otolaryngologists, and plastic surgeons. These surgeons are trained in the comprehensive management of trauma to the lower, middle and upper face and have to take written and oral board examinations covering the management of facial injuries.

Prognosis and complications

By itself, facial trauma rarely presents a threat to life; however it is often associated with dangerous injuries, and life-threatening complications such as blockage of the airway may occur. The airway can be blocked due to bleeding, swelling of surrounding tissues, or damage to structures. Burns to the face can cause swelling of tissues and thereby lead to airway blockage. Broken bones such as combinations of nasal, maxillary, and mandibular fractures can interfere with the airway. Blood from the face or mouth, if swallowed, can cause vomiting, which can itself present a threat to the airway because it has the potential to be aspirated. Since airway problems can occur late after the initial injury, it is necessary for healthcare providers to monitor the airway regularly.

Even when facial injuries are not life-threatening, they have the potential to cause disfigurement and disability, with long-term physical and emotional results. Facial injuries can cause problems with eye, nose, or jaw function and can threaten eyesight. As early as 400 BC, Hippocrates is thought to have recorded a relationship between blunt facial trauma and blindness. Injuries involving the eye or eyelid, such as retrobulbar hemorrhage, can threaten eyesight; however, blindness following facial trauma is not common.

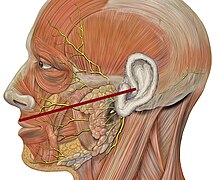

Incising wounds of the face may involve the parotid duct. This is more likely if the wound crosses a line drawn between the tragus of the ear to the upper lip. The approximate location of the course of the duct is the middle third of this line.

Nerves and muscles may be trapped by broken bones; in these cases the bones need to be put back into their proper places quickly. For example, fractures of the orbital floor or medial orbital wall of the eye can entrap the medial rectus or inferior rectus muscles. In facial wounds, tear ducts and nerves of the face may be damaged. Fractures of the frontal bone can interfere with the drainage of the frontal sinus and can cause sinusitis.

Infection is another potential complication, for example when debris is ground into an abrasion and remains there. Injuries resulting from bites carry a high infection risk.

Epidemiology

As many as 50–70% of people who survive traffic accidents have facial trauma. In most developed countries, violence from other people has replaced vehicle collisions as the main cause of maxillofacial trauma; however in many developing countries traffic accidents remain the major cause. Increased use of seat belts and airbags has been credited with a reduction in the incidence of maxillofacial trauma, but fractures of the mandible (the jawbone) are not decreased by these protective measures. The risk of maxillofacial trauma is decreased by a factor of two with use of motorcycle helmets. A decline in facial bone fractures due to vehicle accidents is thought to be due to seat belt and drunk driving laws, strictly enforced speed limits and use of airbags. In vehicle accidents, drivers and front seat passengers are at highest risk for facial trauma.

Facial fractures are distributed in a fairly normal curve by age, with a peak incidence occurring between ages 20 and 40, and children under 12 have only 5–10% of all facial fractures. Most facial trauma in children involves lacerations and soft tissue injuries. There are several reasons for the lower incidence of facial fractures in children: the face is smaller in relation to the rest of the head, children are less often in some situations associated with facial fractures such as occupational and motor vehicle hazards, there is a lower proportion of cortical bone to cancellous bone in children's faces, poorly developed sinuses make the bones stronger, and fat pads provide protection for the facial bones.

Head and brain injuries are commonly associated with facial trauma, particularly that of the upper face; brain injury occurs in 15–48% of people with maxillofacial trauma. Coexisting injuries can affect treatment of facial trauma; for example they may be emergent and need to be treated before facial injuries. People with trauma above the level of the collar bones are considered to be at high risk for cervical spine injuries (spinal injuries in the neck) and special precautions must be taken to avoid movement of the spine, which could worsen a spinal injury.

References

- ^ Seyfer AE, Hansen JE (2003). pp. 423–24.

- ^ Munter DW, McGurk TD (2002). "Head and facial trauma". In Knoop KJ, Stack LB, Storrow AB (eds.). Atlas of emergency medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Publishing Division. pp. 9–10. ISBN 0-07-135294-5.

- ^ Jordan JR, Calhoun KH (2006). "Management of soft tissue trauma and auricular trauma". In Bailey BJ, Johnson JT, Newlands SD, et al. (eds.). Head & Neck Surgery: Otolaryngology. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 935–36. ISBN 0-7817-5561-1. Archived from the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- ^ Neuman MI, Eriksson E (2006). pp. 1475–77.

- ^ Kellman RM. Commentary on Seyfer AE, Hansen JE (2003). p. 442.

- AlAli, Ahmad M.; Ibrahim, Hussein H. H.; Algharib, Abdullah; Alsaad, Fahad; Rajab, Bashar (August 2021). "Characteristics of pediatric maxillofacial fractures in Kuwait: A single-center retrospective study". Dental Traumatology. 37 (4): 557–561. doi:10.1111/edt.12662. ISSN 1600-9657. PMID 33571399. S2CID 231900892.

- ^ Allsop D, Kennett K (2002). "Skull and facial bone trauma". In Nahum AM, Melvin J (eds.). Accidental injury: Biomechanics and prevention. Berlin: Springer. pp. 254–258. ISBN 0-387-98820-3. Archived from the original on 2017-11-06. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ^ Shapiro AJ, Johnson RM, Miller SF, McCarthy MC (June 2001). "Facial fractures in a level I trauma centre: the importance of protective devices and alcohol abuse". Injury. 32 (5): 353–56. doi:10.1016/S0020-1383(00)00245-X. PMID 11382418.

- ^ Adeyemo WL, Ladeinde AL, Ogunlewe MO, James O (October 2005). "Trends and characteristics of oral and maxillofacial injuries in Nigeria: A review of the literature". Head & Face Medicine. 1 (1): 7. doi:10.1186/1746-160X-1-7. PMC 1277015. PMID 16270942.

- ^ Hunt JP, Weintraub SL, Wang YZ, Buechter KJ (2003). "Kinematics of trauma". In Moore EE, Feliciano DV, Mattox KL (eds.). Trauma. Fifth Edition. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 149. ISBN 0-07-137069-2.

- ^ Jeroukhimov I, Cockburn M, Cohn S (2004). pp.10–11.

- ^ Perry M (March 2008). "Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) and facial trauma: can one size fit all? Part 1: dilemmas in the management of the multiply injured patient with coexisting facial injuries". International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 37 (3): 209–14. doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2007.11.003. PMID 18178381.

- ^ Neuman MI, Eriksson E (2006). pp. 1480–81.

- "Le Fort I fracture" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary.

- ^ Shah AR, Valvassori GE, Roure RM (2006). "Le Fort Fractures". EMedicine. Archived from the original on 2008-10-20.

- "Le Fort II fracture" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary.

- "Le Fort III fracture" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary.

- "Le Fort fracture" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary.

- ^ McIntosh AS, McCrory P (June 2005). "Preventing head and neck injury". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 39 (6): 314–18. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2005.018200. PMC 1725244. PMID 15911597. Archived from the original on 2007-10-09.

- Borzabadi-Farahani A, Borzabadi-Farahani A (December 2011). "The association between orthodontic treatment need and maxillary incisor trauma, a retrospective clinical study". Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics. 112 (6): e75–80. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.05.024. PMID 21880516.

- Borzabadi-Farahani A, Borzabadi-Farahani A, Eslamipour F (October 2010). "An investigation into the association between facial profile and maxillary incisor trauma, a clinical non-radiographic study". Dental Traumatology. 26 (5): 403–8. doi:10.1111/j.1600-9657.2010.00920.x. PMID 20831636.

- ^ Jeroukhimov I, Cockburn M, Cohn S (2004). pp.2–3.

- Perry M, O'Hare J, Porter G (May 2008). "Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) and facial trauma: Can one size fit all? Part 3: Hypovolaemia and facial injuries in the multiply injured patient". International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 37 (5): 405–14. doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2007.11.005. PMID 18262768.

- Dorri, Mojtaba; Nasser, Mona; Oliver, Richard (2009-01-21). "Resorbable versus titanium plates for facial fractures". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD007158. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007158.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 19160326. (Retracted, see doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007158.pub3, PMID 29797347, Retraction Watch)

- ^ Parks SN (2003). "Initial assessment". In Moore EE, Feliciano DV, Mattox KL (eds.). Trauma. Fifth Edition. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 162. ISBN 0-07-137069-2.

- ^ Perry M, Morris C (April 2008). "Advanced trauma life support (ATLS) and facial trauma: Can one size fit all? Part 2: ATLS, maxillofacial injuries and airway management dilemmas". International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 37 (4): 309–20. doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2007.11.002. PMID 18207702.

- Perry M, Dancey A, Mireskandari K, Oakley P, Davies S, Cameron M (August 2005). "Emergency care in facial trauma—A maxillofacial and ophthalmic perspective". Injury. 36 (8): 875–96. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2004.09.018. PMID 16023907.

- Remick, KN; Jackson, TS (July 2010). "Trauma evaluation of the parotid duct in an austere military environment" (PDF). Military Medicine. 175 (7): 539–40. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-09-00128. PMID 20684461. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04.

- Seyfer AE, Hansen JE (2003). p. 434.

- Seyfer AE, Hansen JE (2003). p. 437.

- Neuman MI, Eriksson E (2006). p. 1475. "The age distribution of facial fractures follows a relatively normal curve, with a peak incidence between 20 and 40 years of age."

- Jeroukhimov I, Cockburn M, Cohn S (2004). p. 11. "The incidence of brain injury in patients with maxillofacial trauma varies from 15 to 48%. The risk of serious brain injury is particularly high with upper facial injury."

Cited texts

- Jeroukhimov I, Cockburn M, Cohn S (2004). "Facial trauma: Overview of trauma care". In Thaller SR (ed.). Facial trauma. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker. ISBN 0-8247-4625-2. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- Neuman MI, Eriksson E (2006). "Facial trauma". In Fleisher GR, Ludwig S, Henretig FM (eds.). Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-5074-1. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- Seyfer AE, Hansen JE (2003). "Facial trauma". In Moore EE, Feliciano DV, Mattox KL (eds.). Trauma. Fifth Edition. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 423–24. ISBN 0-07-137069-2.

Further reading

- The Gillies Archives at Queen Mary's Hospital, Sidcup - Documents and images from the early days of reconstructive surgery for severe facial trauma experienced by soldiers in World War I.

External links

| Classification | D |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Nonmusculoskeletal injuries of head (head injury) and neck | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intracranial |

| ||||

| Extracranial/ facial trauma |

| ||||

| Either/both | |||||

| Trauma | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principles | |||||||||

| Assessment |

| ||||||||

| Management |

| ||||||||

| Pathophysiology |

| ||||||||

| Complications | |||||||||