| Class | All-pairs shortest path problem (for weighted graphs) |

|---|---|

| Data structure | Graph |

| Worst-case performance | |

| Best-case performance | |

| Average performance | |

| Worst-case space complexity |

In computer science, the Floyd–Warshall algorithm (also known as Floyd's algorithm, the Roy–Warshall algorithm, the Roy–Floyd algorithm, or the WFI algorithm) is an algorithm for finding shortest paths in a directed weighted graph with positive or negative edge weights (but with no negative cycles). A single execution of the algorithm will find the lengths (summed weights) of shortest paths between all pairs of vertices. Although it does not return details of the paths themselves, it is possible to reconstruct the paths with simple modifications to the algorithm. Versions of the algorithm can also be used for finding the transitive closure of a relation , or (in connection with the Schulze voting system) widest paths between all pairs of vertices in a weighted graph.

History and naming

The Floyd–Warshall algorithm is an example of dynamic programming, and was published in its currently recognized form by Robert Floyd in 1962. However, it is essentially the same as algorithms previously published by Bernard Roy in 1959 and also by Stephen Warshall in 1962 for finding the transitive closure of a graph, and is closely related to Kleene's algorithm (published in 1956) for converting a deterministic finite automaton into a regular expression, with the difference being the use of a min-plus semiring. The modern formulation of the algorithm as three nested for-loops was first described by Peter Ingerman, also in 1962.

Algorithm

The Floyd–Warshall algorithm compares many possible paths through the graph between each pair of vertices. It is guaranteed to find all shortest paths and is able to do this with comparisons in a graph, even though there may be edges in the graph. It does so by incrementally improving an estimate on the shortest path between two vertices, until the estimate is optimal.

Consider a graph with vertices numbered 1 through . Further consider a function that returns the length of the shortest possible path (if one exists) from to using vertices only from the set as intermediate points along the way. Now, given this function, our goal is to find the length of the shortest path from each to each using any vertex in . By definition, this is the value , which we will find recursively.

Observe that must be less than or equal to : we have more flexibility if we are allowed to use the vertex . If is in fact less than , then there must be a path from to using the vertices that is shorter than any such path that does not use the vertex . Since there are no negative cycles this path can be decomposed as:

- (1) a path from to that uses the vertices , followed by

- (2) a path from to that uses the vertices .

And of course, these must be a shortest such path (or several of them), otherwise we could further decrease the length. In other words, we have arrived at the recursive formula:

-

-

- .

-

The base case is given by

where denotes the weight of the edge from to if one exists and ∞ (infinity) otherwise.

These formulas are the heart of the Floyd–Warshall algorithm. The algorithm works by first computing for all pairs for , then , then , and so on. This process continues until , and we have found the shortest path for all pairs using any intermediate vertices. Pseudocode for this basic version follows.

Pseudocode

let dist be a |V| × |V| array of minimum distances initialized to ∞ (infinity)

for each edge (u, v) do

dist ← w(u, v) // The weight of the edge (u, v)

for each vertex v do

dist ← 0

for k from 1 to |V|

for i from 1 to |V|

for j from 1 to |V|

if dist > dist + dist

dist ← dist + dist

end if

Example

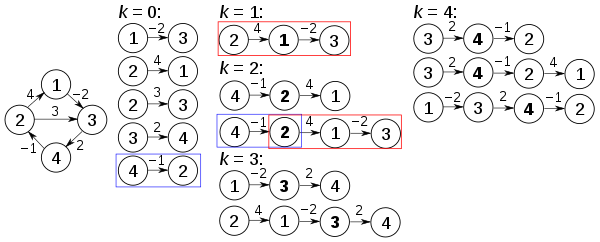

The algorithm above is executed on the graph on the left below:

Prior to the first recursion of the outer loop, labeled k = 0 above, the only known paths correspond to the single edges in the graph. At k = 1, paths that go through the vertex 1 are found: in particular, the path is found, replacing the path which has fewer edges but is longer (in terms of weight). At k = 2, paths going through the vertices {1,2} are found. The red and blue boxes show how the path is assembled from the two known paths and encountered in previous iterations, with 2 in the intersection. The path is not considered, because is the shortest path encountered so far from 2 to 3. At k = 3, paths going through the vertices {1,2,3} are found. Finally, at k = 4, all shortest paths are found.

The distance matrix at each iteration of k, with the updated distances in bold, will be:

| k = 0 | j | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i | 1 | 0 | ∞ | −2 | ∞ |

| 2 | 4 | 0 | 3 | ∞ | |

| 3 | ∞ | ∞ | 0 | 2 | |

| 4 | ∞ | −1 | ∞ | 0 | |

| k = 1 | j | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i | 1 | 0 | ∞ | −2 | ∞ |

| 2 | 4 | 0 | 2 | ∞ | |

| 3 | ∞ | ∞ | 0 | 2 | |

| 4 | ∞ | −1 | ∞ | 0 | |

| k = 2 | j | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i | 1 | 0 | ∞ | −2 | ∞ |

| 2 | 4 | 0 | 2 | ∞ | |

| 3 | ∞ | ∞ | 0 | 2 | |

| 4 | 3 | −1 | 1 | 0 | |

| k = 3 | j | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i | 1 | 0 | ∞ | −2 | 0 |

| 2 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 4 | |

| 3 | ∞ | ∞ | 0 | 2 | |

| 4 | 3 | −1 | 1 | 0 | |

| k = 4 | j | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i | 1 | 0 | −1 | −2 | 0 |

| 2 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 4 | |

| 3 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| 4 | 3 | −1 | 1 | 0 | |

Behavior with negative cycles

A negative cycle is a cycle whose edges sum to a negative value. There is no shortest path between any pair of vertices , which form part of a negative cycle, because path-lengths from to can be arbitrarily small (negative). For numerically meaningful output, the Floyd–Warshall algorithm assumes that there are no negative cycles. Nevertheless, if there are negative cycles, the Floyd–Warshall algorithm can be used to detect them. The intuition is as follows:

- The Floyd–Warshall algorithm iteratively revises path lengths between all pairs of vertices , including where ;

- Initially, the length of the path is zero;

- A path can only improve upon this if it has length less than zero, i.e. denotes a negative cycle;

- Thus, after the algorithm, will be negative if there exists a negative-length path from back to .

Hence, to detect negative cycles using the Floyd–Warshall algorithm, one can inspect the diagonal of the path matrix, and the presence of a negative number indicates that the graph contains at least one negative cycle. During the execution of the algorithm, if there is a negative cycle, exponentially large numbers can appear, as large as , where is the largest absolute value of a negative edge in the graph. To avoid overflow/underflow problems one should check for negative numbers on the diagonal of the path matrix within the inner for loop of the algorithm. Obviously, in an undirected graph a negative edge creates a negative cycle (i.e., a closed walk) involving its incident vertices. Considering all edges of the above example graph as undirected, e.g. the vertex sequence 4 – 2 – 4 is a cycle with weight sum −2.

Path reconstruction

The Floyd–Warshall algorithm typically only provides the lengths of the paths between all pairs of vertices. With simple modifications, it is possible to create a method to reconstruct the actual path between any two endpoint vertices. While one may be inclined to store the actual path from each vertex to each other vertex, this is not necessary, and in fact, is very costly in terms of memory. Instead, we can use the shortest-path tree, which can be calculated for each node in time using memory, and allows us to efficiently reconstruct a directed path between any two connected vertices.

Pseudocode

The array prev holds the penultimate vertex on the path from u to v (except in the case of prev, where it always contains v even if there is no self-loop on v):

let dist be a array of minimum distances initialized to (infinity) let prev be a array of vertex indices initialized to null procedure FloydWarshallWithPathReconstruction() is for each edge (u, v) do dist ← w(u, v) // The weight of the edge (u, v) prev ← u for each vertex v do dist ← 0 prev ← v for k from 1 to |V| do // standard Floyd-Warshall implementation for i from 1 to |V| for j from 1 to |V| if dist > dist + dist then dist ← dist + dist prev ← prev

procedure Path(u, v) is

if prev = null then

return

path ←

while u ≠ v do

v ← prev

path.prepend(v)

return path

Time complexity

Let be , the number of vertices. To find all of (for all and ) from those of requires operations. Since we begin with and compute the sequence of matrices , , , , each having a cost of , the total time complexity of the algorithm is .

Applications and generalizations

The Floyd–Warshall algorithm can be used to solve the following problems, among others:

- Shortest paths in directed graphs (Floyd's algorithm).

- Transitive closure of directed graphs (Warshall's algorithm). In Warshall's original formulation of the algorithm, the graph is unweighted and represented by a Boolean adjacency matrix. Then the addition operation is replaced by logical conjunction (AND) and the minimum operation by logical disjunction (OR).

- Finding a regular expression denoting the regular language accepted by a finite automaton (Kleene's algorithm, a closely related generalization of the Floyd–Warshall algorithm)

- Inversion of real matrices (Gauss–Jordan algorithm)

- Optimal routing. In this application one is interested in finding the path with the maximum flow between two vertices. This means that, rather than taking minima as in the pseudocode above, one instead takes maxima. The edge weights represent fixed constraints on flow. Path weights represent bottlenecks; so the addition operation above is replaced by the minimum operation.

- Fast computation of Pathfinder networks.

- Widest paths/Maximum bandwidth paths

- Computing canonical form of difference bound matrices (DBMs)

- Computing the similarity between graphs

- Transitive closure in AND/OR/threshold graphs.

Implementations

Implementations are available for many programming languages.

- For C++, in the boost::graph library

- For C#, at QuikGraph

- For C#, at QuickGraphPCL (A fork of QuickGraph with better compatibility with projects using Portable Class Libraries.)

- For Java, in the Apache Commons Graph library

- For JavaScript, in the Cytoscape library

- For Julia, in the Graphs.jl package

- For MATLAB, in the Matlab_bgl package

- For Perl, in the Graph module

- For Python, in the SciPy library (module scipy.sparse.csgraph) or NetworkX library

- For R, in packages e1071 and Rfast

- For C, a pthreads, parallelized, implementation including a SQLite interface to the data at floydWarshall.h

Comparison with other shortest path algorithms

For graphs with non-negative edge weights, Dijkstra's algorithm can be used to find all shortest paths from a single vertex with running time . Thus, running Dijkstra starting at each vertex takes time . Since , this yields a worst-case running time of repeated Dijkstra of . While this matches the asymptotic worst-case running time of the Floyd-Warshall algorithm, the constants involved matter quite a lot. When a graph is dense (i.e., ), the Floyd-Warshall algorithm tends to perform better in practice. When the graph is sparse (i.e., is significantly smaller than ), Dijkstra tends to dominate.

For sparse graphs with negative edges but no negative cycles, Johnson's algorithm can be used, with the same asymptotic running time as the repeated Dijkstra approach.

There are also known algorithms using fast matrix multiplication to speed up all-pairs shortest path computation in dense graphs, but these typically make extra assumptions on the edge weights (such as requiring them to be small integers). In addition, because of the high constant factors in their running time, they would only provide a speedup over the Floyd–Warshall algorithm for very large graphs.

References

- ^ Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L. (1990). Introduction to Algorithms (1st ed.). MIT Press and McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-262-03141-8. See in particular Section 26.2, "The Floyd–Warshall algorithm", pp. 558–565 and Section 26.4, "A general framework for solving path problems in directed graphs", pp. 570–576.

- Kenneth H. Rosen (2003). Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications, 5th Edition. Addison Wesley. ISBN 978-0-07-119881-3.

- Floyd, Robert W. (June 1962). "Algorithm 97: Shortest Path". Communications of the ACM. 5 (6): 345. doi:10.1145/367766.368168. S2CID 2003382.

- Roy, Bernard (1959). "Transitivité et connexité". C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris (in French). 249: 216–218.

- Warshall, Stephen (January 1962). "A theorem on Boolean matrices". Journal of the ACM. 9 (1): 11–12. doi:10.1145/321105.321107. S2CID 33763989.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Floyd-Warshall Algorithm". MathWorld.

- Kleene, S. C. (1956). "Representation of events in nerve nets and finite automata". In C. E. Shannon and J. McCarthy (ed.). Automata Studies. Princeton University Press. pp. 3–42.

- Ingerman, Peter Z. (November 1962). "Algorithm 141: Path Matrix". Communications of the ACM. 5 (11): 556. doi:10.1145/368996.369016. S2CID 29010500.

- ^ Hochbaum, Dorit (2014). "Section 8.9: Floyd-Warshall algorithm for all pairs shortest paths" (PDF). Lecture Notes for IEOR 266: Graph Algorithms and Network Flows. Department of Industrial Engineering and Operations Research, University of California, Berkeley. pp. 41–42.

- Stefan Hougardy (April 2010). "The Floyd–Warshall algorithm on graphs with negative cycles". Information Processing Letters. 110 (8–9): 279–281. doi:10.1016/j.ipl.2010.02.001.

- "Free Algorithms Book".

- Baras, John; Theodorakopoulos, George (2022). Path Problems in Networks. Springer International Publishing. ISBN 9783031799839.

- Gross, Jonathan L.; Yellen, Jay (2003), Handbook of Graph Theory, Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications, CRC Press, p. 65, ISBN 9780203490204.

- Penaloza, Rafael. "Algebraic Structures for Transitive Closure". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.71.7650.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Gillies, Donald (1993). Scheduling Tasks with AND/OR precedence contraints (PhD Thesis, Appendix B) (PDF) (Report).

- Zwick, Uri (May 2002), "All pairs shortest paths using bridging sets and rectangular matrix multiplication", Journal of the ACM, 49 (3): 289–317, arXiv:cs/0008011, doi:10.1145/567112.567114, S2CID 1065901.

- Chan, Timothy M. (January 2010), "More algorithms for all-pairs shortest paths in weighted graphs", SIAM Journal on Computing, 39 (5): 2075–2089, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.153.6864, doi:10.1137/08071990x.

External links

- Interactive animation of the Floyd–Warshall algorithm

- Interactive animation of the Floyd–Warshall algorithm (Technical University of Munich)

| Graph and tree traversal algorithms | |

|---|---|

| Search | |

| Shortest path | |

| Minimum spanning tree | |

| List of graph search algorithms | |

| Optimization: Algorithms, methods, and heuristics | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  | |||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

, or (in connection with the

, or (in connection with the  with vertices

with vertices  numbered 1 through

numbered 1 through  . Further consider a function

. Further consider a function  that returns the length of the shortest possible path (if one exists) from

that returns the length of the shortest possible path (if one exists) from  to

to  using vertices only from the set

using vertices only from the set  as intermediate points along the way. Now, given this function, our goal is to find the length of the shortest path from each

as intermediate points along the way. Now, given this function, our goal is to find the length of the shortest path from each  . By definition, this is the value

. By definition, this is the value  , which we will find

, which we will find  : we have more flexibility if we are allowed to use the vertex

: we have more flexibility if we are allowed to use the vertex  . If

. If  , followed by

, followed by

.

.

denotes the weight of the edge from

denotes the weight of the edge from  pairs for

pairs for  , then

, then  , then

, then  , and so on. This process continues until

, and so on. This process continues until  , and we have found the shortest path for all

, and we have found the shortest path for all

;

; is zero;

is zero; can only improve upon this if it has length less than zero, i.e. denotes a negative cycle;

can only improve upon this if it has length less than zero, i.e. denotes a negative cycle; , where

, where  is the largest absolute value of a negative edge in the graph. To avoid overflow/underflow problems one should check for negative numbers on the diagonal of the path matrix within the inner for loop of the algorithm. Obviously, in an undirected graph a negative edge creates a negative cycle (i.e., a closed walk) involving its incident vertices. Considering all edges of the

is the largest absolute value of a negative edge in the graph. To avoid overflow/underflow problems one should check for negative numbers on the diagonal of the path matrix within the inner for loop of the algorithm. Obviously, in an undirected graph a negative edge creates a negative cycle (i.e., a closed walk) involving its incident vertices. Considering all edges of the  time using

time using  memory, and allows us to efficiently reconstruct a directed path between any two connected vertices.

memory, and allows us to efficiently reconstruct a directed path between any two connected vertices.

array of minimum distances initialized to

array of minimum distances initialized to  (infinity)

let prev be a

(infinity)

let prev be a  be

be  , the number of vertices. To find all

, the number of vertices. To find all  of

of

and compute the sequence of

and compute the sequence of  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , each having a cost of

, each having a cost of  .

.

. Thus, running Dijkstra starting at each vertex takes time

. Thus, running Dijkstra starting at each vertex takes time  . Since

. Since  , this yields a worst-case running time of repeated Dijkstra of

, this yields a worst-case running time of repeated Dijkstra of  . While this matches the asymptotic worst-case running time of the Floyd-Warshall algorithm, the constants involved matter quite a lot. When a

. While this matches the asymptotic worst-case running time of the Floyd-Warshall algorithm, the constants involved matter quite a lot. When a  ), the Floyd-Warshall algorithm tends to perform better in practice. When the graph is sparse (i.e.,

), the Floyd-Warshall algorithm tends to perform better in practice. When the graph is sparse (i.e.,  is significantly smaller than

is significantly smaller than  ), Dijkstra tends to dominate.

), Dijkstra tends to dominate.