Anti-personnel and anti-tank mine

| Flame fougasse | |

|---|---|

A demonstration of 'Fougasse', somewhere in Britain. A car is surrounded in flames and a huge cloud of smoke. c 1940. A demonstration of 'Fougasse', somewhere in Britain. A car is surrounded in flames and a huge cloud of smoke. c 1940. | |

| Type | Anti-personnel and anti-tank mine |

| Place of origin | United Kingdom |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1940–present |

| Used by | British Army and Home Guard |

| Wars | Second World War |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Petroleum Warfare Department and William Howard Livens |

| Designed | 1940-41 |

| No. built | 50,000 in Britain |

| Specifications | |

| Rate of fire | Single shot |

| Effective firing range | 30 yd (27 m) |

| Sights | None |

A flame fougasse (sometimes contracted to fougasse and may be spelled foo gas) is a type of mine or improvised explosive device which uses an explosive charge to project burning liquid onto a target. The flame fougasse was developed by the Petroleum Warfare Department in Britain as an anti-tank weapon during the invasion crisis of 1940. During that period, about 50,000 flame fougasse barrels were deployed in some 7,000 batteries, mostly in southern England and a little later at 2,000 sites in Scotland. Although never used in combat in Britain, the design saw action later in Greece.

Later in World War II, Germany and Russia developed flame throwing mines that worked on a somewhat different principle. After World War II, flame fougasses similar to the original British design have been used in several conflicts including the Korean and Vietnam Wars where it was improvised from easily available parts. The flame fougasse remains in army field manuals as a battlefield expedient to the present day.

Development history

Following the Dunkirk evacuation in 1940, Britain faced a shortage of weapons. In particular, there was a severe scarcity of anti-tank weapons, many of which had to be left behind in France. One of the few resources not in short supply was petroleum oil since supplies intended for Europe were filling British storage facilities.

Maurice Hankey, then a cabinet minister without portfolio, joined the Ministerial Committee on Civil Defence (CDC) chaired by Sir John Anderson, the Secretary of State for the Home Office and Home Security. Among many ideas, Hankey "brought out of his stable a hobby horse which he had ridden very hard in the 1914–18 war – namely the use of burning oil for defensive purposes." Hankey believed that oil should not just be denied to an invader, but used to impede him. Towards the end of June, Hankey brought his scheme up at a meeting of the Oil Control Board and produced for Commander-in-Chief Home Forces Edmund Ironside extracts of his paper on experiments with oil in the First World War. On 5 June, Churchill authorised Geoffrey Lloyd, the Secretary for Petroleum to press ahead with experiments with Hankey taking the matter under his general supervision. To this end, the Petroleum Warfare Department (PWD) was created and it was made responsible for developing weapons and tactics. Sir Donald Banks was put in charge of the department.

The PWD soon received the assistance of William Howard Livens. Livens was well known for his First World War invention: the "Livens Gas and Oil Bomb Projector", known more simply as the Livens Projector. The Livens Projector was a large, simple mortar that could throw a projectile containing about 30 pounds (14 kg) of explosives, incendiary oil or, most commonly, poisonous phosgene gas. The great advantage of the Livens Projector was that it was cheap; this allowed hundreds, and on occasions thousands, to be set up and then fired simultaneously catching the enemy by surprise.

One of Livens' PWD demonstrations, probably first seen about mid-July at Dumpton Gap, was particularly promising. A barrel of oil was blown up on the beach; Lloyd was said to have been particularly impressed when he observed a party of high-ranking officers witnessing a test from the top of a cliff making "an instantaneous and precipitate movement to the rear". The work was dangerous; Livens and Banks were experimenting with five-gallon drums in the shingle at Hythe when a short circuit triggered several weapons. By good fortune, the battery of drums where the party was standing failed to go off.

The experiments led to a particularly promising arrangement: a forty-gallon steel drum buried in an earthen bank with just the round front end exposed. At the back of the drum was an explosive which, when triggered, ruptured the drum and shot a jet of flame about 10 feet (3.0 m) wide and 30 yards (27 m) long. The design was reminiscent of a weapon dating from post-medieval times called a fougasse: a hollow in which was placed a barrel of gunpowder covered by rocks, the explosives to be detonated by a fuse at an opportune moment. Livens' new weapon was duly dubbed the flame fougasse. The flame fougasse was demonstrated to Clement Attlee, Maurice Hankey and General Liardet on 20 July 1940.

Experiments by the Fuel Research Station with the flame fougasse continued and it rapidly evolved. The fuel mixture was at first 40% petrol and 60% gas-oil, a mixture calculated to be useless as a vehicle fuel. A concoction of tar, lime, and petrol gel known as 5B was also developed. "5B was dark coloured, sticky, smooth paste which burned fiercely for many minutes, stuck easily to anything with which it came in contact and did not flow on burning." Early flame fougasse designs had a complex arrangement of explosive charges: a small one at the front to ignite the fuel and a main charge at the back to throw the fuel forward. An important discovery was that including magnesium alloy turnings (the waste product of machining magnesium pieces in a lathe) with the main charge at the rear of the barrel would give reliable ignition. This eliminated the need for a separate ignition charge and its associated wiring. The alloy of about 90% magnesium and 10% aluminium was, at the time, known under the trade name Elektron.

Design variations

Of the original British flame fougasse designs, there were three main variants: the safety fougasse, the demigasse and the hedge hopper. They all used metal barrels and similar pre-prepared explosive charges, although they varied in the details of construction and the amount of ammonal used for the propelling charge.

Safety fougasse

The most common form of the flame fougasse was the safety fougasse. This design allowed the propelling charge to be stored separately until needed. The safety fougasse was constructed as follows: a small section was excavated from the side of a slope, leaving a shallow platform of earth, and a barrel of incendiary mixture was placed horizontally in a low position with one round face pointing towards the target. At the back, a section of stove or drain pipe was placed vertically against the rear face of the barrel. The lower end of the pipe was blocked off with a thin cover and positioned a few inches above the bottom of the barrel. The top of the pipe was fitted with a loose cap to keep water out. This pipe is what makes it a "safety" fougasse because it allows later installation of the propelling charge. Soil was then built up over the weapon until all that could be seen were the front disk of the barrel and top of the pipe.

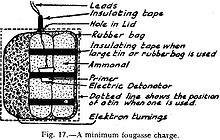

The propelling charge was prepared with an electrically triggered detonator in a primer bound with insulating tape to three or four cartridges of ammonal explosive. This assembly was placed in a small, waterproof rubber bag that was, in turn, placed inside a used cocoa tin. Four ounces (110 g) of magnesium alloy turnings were added to ensure ignition of the fuel. The electrical wires were passed through a small hole in the lid of the tin which was then tightly fitted. The propelling charges were kept in storage, only to be deployed when enemy action was imminent. To activate the device, the propelling charge was lowered down the pipe and tamped down with dry soil before being connected to a firing point about 100 yards (91 m) away. Firing required the current delivered by a 120 V battery.

Private Harold Wimshurst later recalled:

We had a special job. We had to go all round these villages where there are banks and bends in the road and we had to insert these barrels of inflammable material into the banks. A charge was put behind them with a wire running behind them to the nearest cover. A detonator was put in a pipe down the back of these barrels and the idea was that if the tanks came round on the road, we'd detonate these barrels of flaming liquid over them.

A non-safety fougasse could be built by simply burying the propelling charge behind the fuel drum and running leads through the soil. Instructions for several variants of this design were published but this construction increases the hazard because the leads would have to be left exposed on the surface and any electrical current applied could, theoretically, ignite the charge. Also, underground moisture could also easily ruin the charge over an extended period of time.

The safety fougasse design had the advantage that without the propelling charge the fougasse was sufficiently safe that it did not require a guard. Banks records that installing the charge only when there was clear danger relatively close at hand was a safety feature required to protect the public from accidents. The ammonal used for the main propellant charge is a cheap industrial explosive that is notoriously hygroscopic, becoming less effective when it absorbs moisture. Even though the charge was packed into a rubber bag in a tin and sealed with insulating tape, it would not have been a good idea to store it for long in the damp conditions of a flame fougasse installation.

Flame fougasses were camouflaged with a covering of light material such as netting – anything heavier would significantly affect the range. They could easily be merged into hedgerows or the banks of a sunken lane within view of a well-hidden firing point. They were placed where a vehicle would be obliged to stop, or at least slow down. The flame fougasse would offer instant and horrific wounds to any unprotected men caught in its fiery maw and would cause a vehicle engine to stop within seven seconds simply because it was deprived of oxygen (although it would easily start again once the fireball subsided, provided nothing was damaged).

British soldier Fred Lord Hilton MM later recalled:

On one occasion digging in and actually blowing a set of Fougasse—these were 50-imperial-gallon (230 L; 60 US gal) oil drums filled with petrol and oil, buried in the side of a defile with a small charge of explosives behind or underneath. The idea was that when a column of enemy tanks the spot the Fougasse were blown. I don’t know if they were ever used in action but, at the demonstration we did, the flame covered an area of about 50 square yards (42 m) and nothing could have lived in it. I think this would have stopped some of the tanks, of course, this was the whole point of the exercise!

Demigasse

The demigasse was a simpler variant of the flame fougasse. It was a barrel of petroleum mixture laid on its side with a cocoa tin charge in a shallow pit just below one of the barrel's ridges. On detonation, the barrel would rupture and flip over spilling its contents over an area of about 36 square yards (30 m). Left on its own at a roadside, in the open and with no attempt at disguise other than to hide the firing wires, it was indistinguishable from the barrels of tar commonly used in road repair. It was hoped that in addition to the damage done by the weapon itself, experience would cause the enemy to treat every innocent roadside barrel with the greatest caution.

Hedge hopper

Installation diagram

Installation diagram DemonstrationHedge hopper

DemonstrationHedge hopper

Another variant of the flame fougasse was the "hedge hopper". This was a barrel of petroleum mixture placed upright with a cocoa tin charge containing two primers and just one ammonal cartridge buried in an eight-inch (200 mm) deep pit placed underneath and slightly off centre, but carefully aligned with the seam of the barrel. On firing, the barrel would be projected 10 feet (3 m) into the air and 10 yards (9 m) forwards, bounding over a hedge or wall behind which it had been hidden. It was difficult to get the hedge hopper's propelling charge right, but it had the great advantage of being quick to install and easy to conceal.

Home Guard member William Leslie Frost later recalled seeing a hedge hopper in action.

I was most impressed with the full gas hedge-hopper, which consisted of a forty gallon mixture of tar and oil and all sorts of things like that with a charge underneath it; the ideal thing was you waited until an enemy tank was just the other side of a hedge, and you blew it up. The idea was that you just tried to hawk it over the hedge, set it on fire so it smothered the tank and enveloped it in flame. Unfortunately, (or fortunately as it went a bit wrong) one had a bit too much charge underneath it (it was a delicate operation) and it went up in the air in one big ball of fire about 50 feet (15 m) across, very impressive!

Placing the hedge hopper so that it worked properly proved difficult to get right and the War Office discouraged its use in favour of the more conventional flame fougasse installation.

A further variant of the hedge hopper idea was devised for St Margaret's Bay where the barrels would be sent rolling over the cliff edge.

Deployment

In all 50,000 flame fougasse barrels were distributed of which the great majority were installed in 7,000 batteries, mostly in southern England and a little later at 2,000 sites in Scotland. Some barrels were held in reserve while others were deployed at storage sites to destroy petrol depots at short notice. The size of a battery varied from just one drum to as many as fourteen; a four barrel battery was the most common installation and the recommended minimum. Where possible, half the barrels in a battery were to contain the 40/60 mixture and half the sticky 5B mixture.

A battery would be placed at a location such as a corner, steep incline or roadblock where vehicles would be obliged to slow.

Later development

Although the flame fougasse was never used in Britain, the idea was exported to Greece by a couple of PWD officers when, in 1941, German invasion threatened. They were reported to have a powerful effect on enemy units.

By 1942, there were proposals for completely buried flame fougasses to be used as oil mines but by then the emergency was over. Almost all flame fougasses were removed before the end of the war and in most instances even the slightest traces of their original locations have disappeared. A few instances were missed, and their remains have been found. For example, the rusty remnants of a four-barrel battery, one of which still contained an oily residue, were discovered in 2010 in West Sussex.

Both the Russians and the Germans later used weapons described as fougasse flame throwers or flame thrower mines. They worked on a different principle to the flame fougasse. Fougasse flame throwers comprised a cylinder containing a few gallons of petrol and oil; this would be hidden, typically by being buried. On being triggered electrically, either by an operator or by a booby trap mechanism, a gas generator is ignited. The pressure ruptures a thin metal seal and the liquid is forced up a central pipe and out through one or more nozzles. A squib is automatically fired to ignite the fuel. The range of the flame varied considerably, generally just a few tens of yards and lasted only one to two seconds. The German version, the Abwehrflammenwerfer 42, had an 8 imperial gallons (36 L; 9.6 US gal) fuel tank and were wired back to a control point from where they could be fired individually or together.

The flame fougasse has remained in army field manuals as a battlefield expedient to the present day. Such weapons are improvised from available fuel containers combined with standard explosive charges or hand grenades and are triggered electrically or by lengths of detonating cord. In some designs, detonating cord is used to rupture the container immediately before triggering the propelling charge. In order to guarantee ignition, the improvised devices frequently feature two explosive charges, one to throw and the other to ignite the fuel. Weapons of this sort were widely used in the Korean and Vietnam Wars as well as other conflicts.

See also

- British anti-invasion preparations of World War II

- British hardened field defences of World War II

- Improvised explosive device

- Lagonda flamethrower

- List of flamethrowers

- Molotov cocktail

- Petroleum Warfare Department

References

Explanatory footnotes

- Livens had briefly experimented with a similar weapons during the First World War.

- Although the standard capacity is 44 imperial gallons (55 US gallons), historical records generally refer to 40-gallon drums and sometimes 50-gallon drums apparently interchangeably.

Citations

- ^ Barrel Flame Traps 1942, p. 6.

- "Dictionary". Vietnam. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- Dear & Foot 2001, p. 296.

- ^ Banks 1946, p. 38.

- ^ FM 20-33. Combat Flame Operations.

- Banks 1946, p. 27.

- Roskill 1974, p. 471.

- ^ Roskill 1974, p. 472.

- ^ Banks 1946, p. 34.

- ^ Banks 1946, p. 33.

- Livens WH Captain – WO 339/19021. The Catalogue, The National Archives

- Jones 2007, p. 27.

- Palazzo 2002, p. 103.

- Gas and Chemical Supplies – MUN 5/385 pp. 9–12. The Catalogue, The National Archives

- Foulkes 2001, p. 167.

- Fuel Research 1917-1958. A review of the Fuel Research Organisation of the DSIR. London: HMSO. 1960. pp. 105–6.

- ^ Flame Fougasses – WO 199/1433. The Catalogue, The National Archives

- Clarke 2011, p. 176.

- ^ Barrel Flame Traps 1942, p. 8.

- ^ Barrel Flame Traps 1942.

- IWM Film MGH 6799, time: 1:02.

- Barrel Flame Traps 1942, pp. 13–18.

- IWM Film MGH 6799, time: 0:02.

- ^ Barrel Flame Traps 1942, pp. 20–21.

- Levine 2007, Private Harold Wilmshurst, p. 63.

- ^ Imperial War Museum. Film WOY35: Flame Fougasse & Barrel Flame Traps.

- ^ Banks 1946, p. 36.

- Barrel Flame Traps 1942, p. 15.

- "Recollections (joining forces and training prior to invasion of Normandy)". WW2 People's War. BBC History. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- IWM Film MGH 6799, time: 3:18.

- IWM Film MGH 6799, time: 2:57.

- Barrel Flame Traps 1942, pp. 10–12.

- "Memoirs of William Leslie Frost, a member of the Home Guard who recalled the hedge hopper weapon in action". South Staffordshire Home Guard website. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- Clarke 2011, p. 174.

- Fleming 1957, p. 208.

- Adrian Armishaw. "Flame Fougasse (surviving remains)". Pillbox Study Group. Archived from the original on 18 January 2008. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- Oil Mines – SUPP 15/33. The Catalogue, The National Archives

- Adrian Armishaw. "Flame Fougasse (surviving remains)". Pillbox Study Group. Archived from the original on 18 January 2008. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ""Fougasse Flame Throwers" from Intelligence Bulletin, November 1944". lonesentry.com. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- Westwood 2005, p. 48.

- "Flame Field Expedients". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

General and cited references

- Banks, Sir Donald (1946). Flame Over Britain. Sampson Low, Marston and Co.

- Clarke, D. M. (2011). "Arming the British Home Guard, 1940–1944". Cranfield University. hdl:1826/6164.

- Dear, Ian; Foot, MRD (2001). The Oxford Companion to World War II. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860446-4.

- Fleming, Peter (1957). Invasion 1940. Rupert Hart-Davis.

- Foulkes, Charles Howard (2001) . "Gas!" The Story of the Special Brigade (Naval & Military Press ed.). Blackwood & Sons. ISBN 1-84342-088-0.

- Jones, Simon (2007). World War I Gas Warfare Tactics and Equipment. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-151-9. Archived from the original on 16 October 2006. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- Levine, Joshua (2007). Forgotten Voices of the Blitz and the Battle of Britain. Ebury Press. ISBN 978-0-09-191004-4.

- Palazzo, Albert (2002). Seeking Victory on the Western Front: The British Army and Chemical Warfare in World War I. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-8774-7.

- Roskill, Stephen (1974). Hankey: Man of Secrets (1931–1963). Vol. III. Collins. ISBN 0-00-211332-5.

- Westwood, David (2005). German Infantryman (3) Eastern Front 1943–45. Warrior. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-780-2.

- Barrel Flame Traps, Flame Warfare. Military Training Pamphlet No. 53. Part 1. War Office. July 1942.

- Application for Appointment to a Temporary Commission in the Regular Army for the Period of the War: William Howard Livens. National Archives WO 339/19021. War Office. 1914.

- Minutes of Proceedings Before the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors. National Archives T 173/702. Treasury. 29 May 1922.

- FM 20-33: Combat Flame Operations. Headquarters Department of the Army. 1967.

- Livens Projector M1. United States Department of War. 1942.

Collections

- "The National Archives". Repository of UK government records. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- "WW2 People's War". BBC. Retrieved 26 August 2010. WW2 People's War is an online archive of wartime memories contributed by members of the public and gathered by the BBC. The archive can be found at bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar.

Imperial War Museum documents

- MGH 6799 – Petroleum Warfare (Film). Imperial War Museum. 1941. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

Further reading

- "British Fire Traps Awaited Invaders". Now It Can Be Told. Popular Science. August 1945. p. 66.

External links

- "WARTIME SECRETS: FLAME FOUGASSE". Discovery Channel.

- "Home Guard 'Fougasse' Demonstration". Photo gallery. King's Own Royal Regiment Museum Lancaster.

- Defence by Fire. British Pathe. 1945. Retrieved 31 May 2015. Burning seas (from the start), flame barrage (from 2:10), hedge hopper (from 3:28), fougasse (from 3:59), Cockatrice (from 4:32). Note that the narrator gives an exaggerated account and repeats some propaganda as fact.