In fluid dynamics, a vortex (pl.: vortices or vortexes) is a region in a fluid in which the flow revolves around an axis line, which may be straight or curved. Vortices form in stirred fluids, and may be observed in smoke rings, whirlpools in the wake of a boat, and the winds surrounding a tropical cyclone, tornado or dust devil.

Vortices are a major component of turbulent flow. The distribution of velocity, vorticity (the curl of the flow velocity), as well as the concept of circulation are used to characterise vortices. In most vortices, the fluid flow velocity is greatest next to its axis and decreases in inverse proportion to the distance from the axis.

In the absence of external forces, viscous friction within the fluid tends to organise the flow into a collection of irrotational vortices, possibly superimposed to larger-scale flows, including larger-scale vortices. Once formed, vortices can move, stretch, twist, and interact in complex ways. A moving vortex carries some angular and linear momentum, energy, and mass, with it.

Overview

In the dynamics of fluid, a vortex is fluid that revolves around the line of flow. This flow of fluid might be curved or straight. Vortices form from stirred fluids: they might be observed in smoke rings, whirlpools, in the wake of a boat or the winds around a tornado or dust devil.

Vortices are an important part of turbulent flow. Vortices can otherwise be known as a circular motion of a liquid. In the cases of the absence of forces, the liquid settles. This makes the water stay still instead of moving.

When they are created, vortices can move, stretch, twist and interact in complicated ways. When a vortex is moving, sometimes, it can affect an angular position.

For an example, if a water bucket is rotated or spun constantly, it will rotate around an invisible line called the axis line. The rotation moves around in circles. In this example the rotation of the bucket creates extra force.

The reason that the vortices can change shape is the fact that they have open particle paths. This can create a moving vortex. Examples of this fact are the shapes of tornadoes and drain whirlpools.

When two or more vortices are close together they can merge to make a vortex. Vortices also hold energy in its rotation of the fluid. If the energy is never removed, it would consist of circular motion forever.

Properties

Vorticity

A key concept in the dynamics of vortices is the vorticity, a vector that describes the local rotary motion at a point in the fluid, as would be perceived by an observer that moves along with it. Conceptually, the vorticity could be observed by placing a tiny rough ball at the point in question, free to move with the fluid, and observing how it rotates about its center. The direction of the vorticity vector is defined to be the direction of the axis of rotation of this imaginary ball (according to the right-hand rule) while its length is twice the ball's angular velocity. Mathematically, the vorticity is defined as the curl (or rotational) of the velocity field of the fluid, usually denoted by and expressed by the vector analysis formula , where is the nabla operator and is the local flow velocity.

The local rotation measured by the vorticity must not be confused with the angular velocity vector of that portion of the fluid with respect to the external environment or to any fixed axis. In a vortex, in particular, may be opposite to the mean angular velocity vector of the fluid relative to the vortex's axis.

Vortex types

In theory, the speed u of the particles (and, therefore, the vorticity) in a vortex may vary with the distance r from the axis in many ways. There are two important special cases, however:

- If the fluid rotates like a rigid body – that is, if the angular rotational velocity Ω is uniform, so that u increases proportionally to the distance r from the axis – a tiny ball carried by the flow would also rotate about its center as if it were part of that rigid body. In such a flow, the vorticity is the same everywhere: its direction is parallel to the rotation axis, and its magnitude is equal to twice the uniform angular velocity Ω of the fluid around the center of rotation.

- If the particle speed u is inversely proportional to the distance r from the axis, then the imaginary test ball would not rotate over itself; it would maintain the same orientation while moving in a circle around the vortex axis. In this case the vorticity is zero at any point not on that axis, and the flow is said to be irrotational.

Irrotational vortices

In the absence of external forces, a vortex usually evolves fairly quickly toward the irrotational flow pattern, where the flow velocity u is inversely proportional to the distance r. Irrotational vortices are also called free vortices.

For an irrotational vortex, the circulation is zero along any closed contour that does not enclose the vortex axis; and has a fixed value, Γ, for any contour that does enclose the axis once. The tangential component of the particle velocity is then . The angular momentum per unit mass relative to the vortex axis is therefore constant, .

The ideal irrotational vortex flow in free space is not physically realizable, since it would imply that the particle speed (and hence the force needed to keep particles in their circular paths) would grow without bound as one approaches the vortex axis. Indeed, in real vortices there is always a core region surrounding the axis where the particle velocity stops increasing and then decreases to zero as r goes to zero. Within that region, the flow is no longer irrotational: the vorticity becomes non-zero, with direction roughly parallel to the vortex axis. The Rankine vortex is a model that assumes a rigid-body rotational flow where r is less than a fixed distance r0, and irrotational flow outside that core regions.

In a viscous fluid, irrotational flow contains viscous dissipation everywhere, yet there are no net viscous forces, only viscous stresses. Due to the dissipation, this means that sustaining an irrotational viscous vortex requires continuous input of work at the core (for example, by steadily turning a cylinder at the core). In free space there is no energy input at the core, and thus the compact vorticity held in the core will naturally diffuse outwards, converting the core to a gradually-slowing and gradually-growing rigid-body flow, surrounded by the original irrotational flow. Such a decaying irrotational vortex has an exact solution of the viscous Navier–Stokes equations, known as a Lamb–Oseen vortex.

Rotational vortices

A rotational vortex – a vortex that rotates in the same way as a rigid body – cannot exist indefinitely in that state except through the application of some extra force, that is not generated by the fluid motion itself. It has non-zero vorticity everywhere outside the core. Rotational vortices are also called rigid-body vortices or forced vortices.

For example, if a water bucket is spun at constant angular speed w about its vertical axis, the water will eventually rotate in rigid-body fashion. The particles will then move along circles, with velocity u equal to wr. In that case, the free surface of the water will assume a parabolic shape.

In this situation, the rigid rotating enclosure provides an extra force, namely an extra pressure gradient in the water, directed inwards, that prevents transition of the rigid-body flow to the irrotational state.

Vortex formation on boundaries

Vortex structures are defined by their vorticity, the local rotation rate of fluid particles. They can be formed via the phenomenon known as boundary layer separation which can occur when a fluid moves over a surface and experiences a rapid acceleration from the fluid velocity to zero due to the no-slip condition. This rapid negative acceleration creates a boundary layer which causes a local rotation of fluid at the wall (i.e. vorticity) which is referred to as the wall shear rate. The thickness of this boundary layer is proportional to (where v is the free stream fluid velocity and t is time).

If the diameter or thickness of the vessel or fluid is less than the boundary layer thickness then the boundary layer will not separate and vortices will not form. However, when the boundary layer does grow beyond this critical boundary layer thickness then separation will occur which will generate vortices.

This boundary layer separation can also occur in the presence of combatting pressure gradients (i.e. a pressure that develops downstream). This is present in curved surfaces and general geometry changes like a convex surface. A unique example of severe geometric changes is at the trailing edge of a bluff body where the fluid flow deceleration, and therefore boundary layer and vortex formation, is located.

Another form of vortex formation on a boundary is when fluid flows perpendicularly into a wall and creates a splash effect. The velocity streamlines are immediately deflected and decelerated so that the boundary layer separates and forms a toroidal vortex ring.

Vortex geometry

In a stationary vortex, the typical streamline (a line that is everywhere tangent to the flow velocity vector) is a closed loop surrounding the axis; and each vortex line (a line that is everywhere tangent to the vorticity vector) is roughly parallel to the axis. A surface that is everywhere tangent to both flow velocity and vorticity is called a vortex tube. In general, vortex tubes are nested around the axis of rotation. The axis itself is one of the vortex lines, a limiting case of a vortex tube with zero diameter.

According to Helmholtz's theorems, a vortex line cannot start or end in the fluid – except momentarily, in non-steady flow, while the vortex is forming or dissipating. In general, vortex lines (in particular, the axis line) are either closed loops or end at the boundary of the fluid. A whirlpool is an example of the latter, namely a vortex in a body of water whose axis ends at the free surface. A vortex tube whose vortex lines are all closed will be a closed torus-like surface.

A newly created vortex will promptly extend and bend so as to eliminate any open-ended vortex lines. For example, when an airplane engine is started, a vortex usually forms ahead of each propeller, or the turbofan of each jet engine. One end of the vortex line is attached to the engine, while the other end usually stretches out and bends until it reaches the ground.

When vortices are made visible by smoke or ink trails, they may seem to have spiral pathlines or streamlines. However, this appearance is often an illusion and the fluid particles are moving in closed paths. The spiral streaks that are taken to be streamlines are in fact clouds of the marker fluid that originally spanned several vortex tubes and were stretched into spiral shapes by the non-uniform flow velocity distribution.

Pressure in a vortex

The fluid motion in a vortex creates a dynamic pressure (in addition to any hydrostatic pressure) that is lowest in the core region, closest to the axis, and increases as one moves away from it, in accordance with Bernoulli's principle. One can say that it is the gradient of this pressure that forces the fluid to follow a curved path around the axis.

In a rigid-body vortex flow of a fluid with constant density, the dynamic pressure is proportional to the square of the distance r from the axis. In a constant gravity field, the free surface of the liquid, if present, is a concave paraboloid.

In an irrotational vortex flow with constant fluid density and cylindrical symmetry, the dynamic pressure varies as P∞ − K/r, where P∞ is the limiting pressure infinitely far from the axis. This formula provides another constraint for the extent of the core, since the pressure cannot be negative. The free surface (if present) dips sharply near the axis line, with depth inversely proportional to r. The shape formed by the free surface is called a hyperboloid, or "Gabriel's Horn" (by Evangelista Torricelli).

The core of a vortex in air is sometimes visible because water vapor condenses as the low pressure of the core causes adiabatic cooling; the funnel of a tornado is an example. When a vortex line ends at a boundary surface, the reduced pressure may also draw matter from that surface into the core. For example, a dust devil is a column of dust picked up by the core of an air vortex attached to the ground. A vortex that ends at the free surface of a body of water (like the whirlpool that often forms over a bathtub drain) may draw a column of air down the core. The forward vortex extending from a jet engine of a parked airplane can suck water and small stones into the core and then into the engine.

Evolution

Vortices need not be steady-state features; they can move and change shape. In a moving vortex, the particle paths are not closed, but are open, loopy curves like helices and cycloids. A vortex flow might also be combined with a radial or axial flow pattern. In that case the streamlines and pathlines are not closed curves but spirals or helices, respectively. This is the case in tornadoes and in drain whirlpools. A vortex with helical streamlines is said to be solenoidal.

As long as the effects of viscosity and diffusion are negligible, the fluid in a moving vortex is carried along with it. In particular, the fluid in the core (and matter trapped by it) tends to remain in the core as the vortex moves about. This is a consequence of Helmholtz's second theorem. Thus vortices (unlike surface waves and pressure waves) can transport mass, energy and momentum over considerable distances compared to their size, with surprisingly little dispersion. This effect is demonstrated by smoke rings and exploited in vortex ring toys and guns.

Two or more vortices that are approximately parallel and circulating in the same direction will attract and eventually merge to form a single vortex, whose circulation will equal the sum of the circulations of the constituent vortices. For example, an airplane wing that is developing lift will create a sheet of small vortices at its trailing edge. These small vortices merge to form a single wingtip vortex, less than one wing chord downstream of that edge. This phenomenon also occurs with other active airfoils, such as propeller blades. On the other hand, two parallel vortices with opposite circulations (such as the two wingtip vortices of an airplane) tend to remain separate.

Vortices contain substantial energy in the circular motion of the fluid. In an ideal fluid this energy can never be dissipated and the vortex would persist forever. However, real fluids exhibit viscosity and this dissipates energy very slowly from the core of the vortex. It is only through dissipation of a vortex due to viscosity that a vortex line can end in the fluid, rather than at the boundary of the fluid.

Further examples

- In the hydrodynamic interpretation of the behaviour of electromagnetic fields, the acceleration of electric fluid in a particular direction creates a positive vortex of magnetic fluid. This in turn creates around itself a corresponding negative vortex of electric fluid. Exact solutions to classical nonlinear magnetic equations include the Landau–Lifshitz equation, the continuum Heisenberg model, the Ishimori equation, and the nonlinear Schrödinger equation.

- Vortex rings are torus-shaped vortices where the axis of rotation is a continuous closed curve. Smoke rings and bubble rings are two well-known examples.

- The lifting force of aircraft wings, propeller blades, sails, and other airfoils can be explained by the creation of a vortex superimposed on the flow of air past the wing.

- Aerodynamic drag can be explained in large part by the formation of vortices in the surrounding fluid that carry away energy from the moving body.

- Large whirlpools can be produced by ocean tides in certain straits or bays. Examples are Charybdis of classical mythology in the Straits of Messina, Italy; the Naruto whirlpools of Nankaido, Japan; and the Maelstrom at Lofoten, Norway.

- Vortices in the Earth's atmosphere are important phenomena for meteorology. They include mesocyclones on the scale of a few miles, tornadoes, waterspouts, and hurricanes. These vortices are often driven by temperature and humidity variations with altitude. The sense of rotation of hurricanes is influenced by the Earth's rotation. Another example is the Polar vortex, a persistent, large-scale cyclone centered near the Earth's poles, in the middle and upper troposphere and the stratosphere.

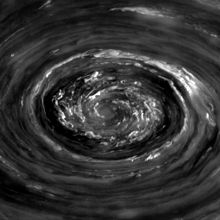

- Vortices are prominent features of the atmospheres of other planets. They include the permanent Great Red Spot on Jupiter, the intermittent Great Dark Spot on Neptune, the polar vortices of Venus, the Martian dust devils and the North Polar Hexagon of Saturn.

- Sunspots are dark regions on the Sun's visible surface (photosphere) marked by a lower temperature than its surroundings, and intense magnetic activity.

- The accretion disks of black holes and other massive gravitational sources.

- Taylor–Couette flow occurs in a fluid between two nested cylinders, one rotating, the other fixed.

See also

- Artificial gravity – Use of circular rotational force to mimic gravity

- Batchelor vortex – fluid dynamics equationPages displaying wikidata descriptions as a fallback

- Biot–Savart law – Important law of classical magnetism

- Coordinate rotation – Motion of a certain space that preserves at least one pointPages displaying short descriptions of redirect targets

- Cyclonic separation – Method of removing particulates from a fluid stream through vortex separation

- Eddy – Swirling of a fluid and the reverse current created when the fluid is in a turbulent flow regime

- Gyre – Any large system of circulating ocean surface currentsPages displaying short descriptions of redirect targets

- Helmholtz's theorems – 3D motion of fluid near vortex lines

- History of fluid mechanics

- Horseshoe vortex – system present in the flow of air around a wingPages displaying wikidata descriptions as a fallback

- Hurricane – Type of rapidly rotating storm systemPages displaying short descriptions of redirect targets

- Kármán vortex street – Repeating pattern of swirling vortices

- Kelvin–Helmholtz instability – Phenomenon of fluid mechanics

- Quantum vortex – Quantized flux circulation of some physical quantity

- Rankine vortex – Mathematical formula for viscous fluid

- Shower-curtain effect – Effect in physics

- Strouhal number – Dimensionless number describing oscillating flow mechanisms

- Vortex engine – Alternative to tall chimneys

- Vortex tube – Device for separating compressed gas into hot and cold streams

- Vortex tunnel – Device for various rides and attractionsPages displaying short descriptions of redirect targets

- Vortex cooler – Device for separating compressed gas into hot and cold streamsPages displaying short descriptions of redirect targets

- VORTEX projects – Field experiments that study tornadoes

- Vortex shedding – Oscillating flow effect resulting from fluid passing over a blunt body

- Vortex stretching – Lengthening of vortices in 3D fluid flow

- Vortex-induced vibration – Motions induced on bodies within a fluid flow due to vortices in the fluid

- Vorticity – Pseudovector field describing the local rotation of a continuum near some point

- Whirly tube – Whirling aerophone

- Wormhole – Hypothetical topological feature of spacetime

References

Notes

- "vortex". Oxford Dictionaries Online (ODO). Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on February 3, 2013. Retrieved 2015-08-29.

- "vortex". Merriam-Webster Online. Merriam-Webster, Inc. Retrieved 2015-08-29.

- Ting, L. (1991). Viscous Vortical Flows. Lecture notes in physics. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-53713-7.

- Kida, Shigeo (2001). Life, Structure, and Dynamical Role of Vortical Motion in Turbulence (PDF). IUTAMim Symposium on Tubes, Sheets and Singularities in Fluid Dynamics. Zakopane, Poland.

- Vallis, Geoffrey (1999). Geostrophic Turbulence: The Macroturbulence of the Atmosphere and Ocean Lecture Notes (PDF). Princeton University. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-28. Retrieved 2012-09-26.

- ^ Clancy 1975, sub-section 7.5

- Sirakov, B. T.; Greitzer, E. M.; Tan, C. S. (2005). "A note on irrotational viscous flow". Physics of Fluids. 17 (10): 108102–108102–3. Bibcode:2005PhFl...17j8102S. doi:10.1063/1.2104550. ISSN 1070-6631.

- Kheradvar, Arash; Pedrizzetti, Gianni (2012), "Vortex Dynamics", Vortex Formation in the Cardiovascular System, London: Springer London, pp. 17–44, doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-2288-3_2, ISBN 978-1-4471-2287-6, retrieved 2021-03-16

Other

- Loper, David E. (November 1966). An analysis of confined magnetohydrodynamic vortex flows (PDF) (NASA contractor report NASA CR-646). Washington: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. LCCN 67060315.

- Batchelor, G.K. (1967). An Introduction to Fluid Dynamics. Cambridge Univ. Press. Ch. 7 et seq. ISBN 9780521098175.

- Falkovich, G. (2011). Fluid Mechanics, a short course for physicists. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-00575-4.

- Clancy, L.J. (1975). Aerodynamics. London: Pitman Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-0-273-01120-0.

- De La Fuente Marcos, C.; Barge, P. (2001). "The effect of long-lived vortical circulation on the dynamics of dust particles in the mid-plane of a protoplanetary disc". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 323 (3): 601–614. Bibcode:2001MNRAS.323..601D. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2001.04228.x.

External links

- Optical Vortices

- Video of two water vortex rings colliding (MPEG)

- Chapter 3 Rotational Flows: Circulation and Turbulence

- Vortical Flow Research Lab (MIT) – Study of flows found in nature and part of the Department of Ocean Engineering.

and expressed by the

and expressed by the  , where

, where  is the

is the  is the local flow velocity.

is the local flow velocity.

. The angular momentum per unit mass relative to the vortex axis is therefore constant,

. The angular momentum per unit mass relative to the vortex axis is therefore constant,  .

.

(where v is the free stream fluid velocity and t is time).

(where v is the free stream fluid velocity and t is time).