Freeze-casting, also frequently referred to as ice-templating, freeze casting, or freeze alignment, is a technique that exploits the highly anisotropic solidification behavior of a solvent (generally water) in a well-dispersed solution or slurry to controllably template directionally porous ceramics, polymers, metals and their hybrids. By subjecting an aqueous solution or slurry to a directional temperature gradient, ice crystals will nucleate on one side and grow along the temperature gradient. The ice crystals will redistribute the dissolved substance and the suspended particles as they grow within the solution or slurry, effectively templating the ingredients that are distributed in the solution or slurry.

Once solidification has ended, the frozen, templated composite is placed into a freeze-dryer to remove the ice crystals. The resulting green body contains anisotropic macropores in a replica of the sublimated ice crystals and structures from micropores to nacre-like packing between the ceramic or metal particles in the walls. The walls templated by the morphology of the ice crystals often show unilateral features. These together build a hierarchically structured cellular structure. This structure is often sintered for metals and ceramics, and crosslinked for polymers, to consolidate the particulate walls and provide strength to the porous material. The porosity left by the sublimation of solvent crystals is typically between 2–200 μm.

Overview

The first observation of cellular structures resulting from the freezing of water goes back over a century, but the first reported instance of freeze-casting, in the modern sense, was in 1954 when Maxwell et al. attempted to fabricate turbosupercharger blades out of refractory powders. They froze extremely thick slips of titanium carbide, producing near-net-shape castings that were easy to sinter and machine. The goal of this work, however, was to make dense ceramics. It was not until 2001, when Fukasawa et al. created directionally porous alumina castings, that the idea of using freeze-casting as a means of creating novel porous structures really took hold. Since that time, research has grown considerably with hundreds of papers coming out within the last decade.

The principles of freeze casting are applicable to a broad range of combinations of particles and suspension media. Water is by far the most commonly used suspension media, and by freeze drying is readily conducive to the step of sublimation that is necessary for the success of freeze-casting processes. Due to the high level of control and broad range of possible porous microstructures that freeze-casting can produce, the technique has been adopted in disparate fields such as tissue scaffolds, photonics, metal-matrix composites, dentistry, materials science, and even food science.

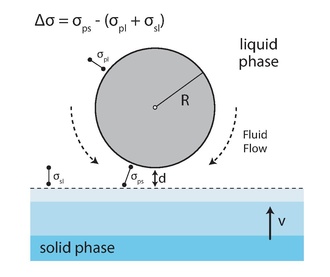

There are three possible end results to uni-directionally freezing a suspension of particles. First, the ice-growth proceeds as a planar front, pushing particles in front like a bulldozer pushes a pile of rocks. This scenario usually occurs at very low solidification velocities (< 1 μm s) or with extremely fine particles because they can move by Brownian motion away from the front. The resultant structure contains no macroporosity. If one were to increase the solidification speed, the size of the particles or solid loading moderately, the particles begin to interact in a meaningful way with the approaching ice front. The result is typically a lamellar or cellular templated structure whose exact morphology depends on the particular conditions of the system. It is this type of solidification that is targeted for porous materials made by freeze-casting. The third possibility for a freeze-cast structure occurs when particles are given insufficient time to segregate from the suspension, resulting in complete encapsulation of the particles within the ice front. This occurs when the freezing rates are rapid, particle size becomes sufficiently large, or when the solids loading is high enough to hinder particle motion. To ensure templating, the particles must be ejected from the oncoming front. Energetically speaking, this will occur if there is an overall increase in free energy if the particle were to be engulfed (Δσ > 0).

where Δσ is the change in free energy of the particle, σps is the surface potential between the particle and interface, σpl is the potential between the particle and the liquid phase and σsl is the surface potential between the solid and liquid phases. This expression is valid at low solidification velocities, when the system is shifted only slightly from equilibrium. At high solidification velocities, kinetics must also be taken into consideration. There will be a liquid film between the front and particle to maintain constant transport of the molecules which are incorporated into the growing crystal. When the front velocity increases, this film thickness (d) will decrease due to increasing drag forces. A critical velocity (vc) occurs when the film is no longer thick enough to supply the needed molecular supply. At this speed the particle will be engulfed. Most authors express vc as a function of particle size where . The transition from a porous R (lamellar) morphology to one where the majority of particles are entrapped occurs at vc, which is generally determined as:

where a0 is the average intermolecular distance of the molecule that is freezing within the liquid, d is the overall thickness of the liquid film, η is the solution viscosity, R is the particle radius and z is an exponent that can vary from 1 to 5. As expected, vc decreases as particle radius R goes up.

Waschkies et al. studied the structure of dilute to concentrated freeze-casts from low (< 1 μm s) to extremely high (> 700 μm s) solidification velocities. From this study, they were able to generate morphological maps for freeze-cast structures made under various conditions. Maps such as these are excellent for showing general trends, but they are quite specific to the materials system from which they were derived. For most applications where freeze-casts will be used after freezing, binders are needed to supply strength in the green state. The addition of binder can significantly alter the chemistry within the frozen environment, depressing the freezing point and hampering particle motion leading to particle entrapment at speeds far below the predicted vc. Assuming, however, that we are operating at speeds below vc and above those which produce a planar front, we will achieve some cellular structure with both ice-crystals and walls composed of packed ceramic particles. The morphology of this structure is tied to some variables, but the most influential is the temperature gradient as a function of time and distance along the freezing direction.

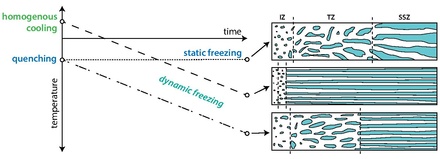

Freeze-cast structures have at least three apparent morphological regions. At the side where freezing initiates is a nearly isotropic region with no visible macropores dubbed the Initial Zone (IZ). Directly after the IZ is the Transition Zone (TZ), where macropores begin to form and align with one another. The pores in this region may appear randomly oriented. The third zone is called the Steady-State Zone (SSZ), macropores in this region are aligned with one another and grow in a regular fashion. Within the SSZ, the structure is defined by a value λ that is the average thickness of a ceramic wall and its adjacent macropore.

Initial zone: nucleation and growth mechanisms

Although the ability of ice to reject suspended particles in the growth process has long been known, the mechanism remains the subject of some discussion. It was believed initially that during the moments immediately following the nucleation of the ice crystals, particles are rejected from the growing planar ice front, leading to the formation of a constitutionally super-cooled zone directly ahead of the growing ice. This unstable region eventually results in perturbations, breaking the planar front into a columnar ice front, a phenomenon better known as a Mullins-Serkerka instability. After the breakdown, the ice crystals grow along the temperature gradient, pushing ceramic particles from the liquid phase aside so that they accumulate between the growing ice crystals. However, recent in-situ X-ray radiography of directionally frozen alumina suspensions reveal a different mechanism.

Transition zone: a changing microstructure

As solidification slows and growth kinetics become rate-limiting, the ice crystals begin to exclude the particles, redistributing them within the suspension. A competitive growth process develops between two crystal populations, those with their basal planes aligned with the thermal gradient (z-crystals) and those that are randomly oriented (r-crystals) giving rise to the start of the TZ.

There are colonies of similarly aligned ice crystals growing throughout the suspension. There are fine lamellae of aligned z-crystals growing with their basal planes aligned with the thermal gradient. The r-crystals appear in this cross-section as platelets but in actuality, they are most similar to columnar dendritic crystals cut along a bias. Within the transition zone, the r-crystals either stop growing or turn into z-crystals that eventually become the predominant orientation, and lead to steady-state growth. There are some reasons why this occurs. For one, during freezing, the growing crystals tend to align with the temperature gradient, as this is the lowest energy configuration and thermodynamically preferential. Aligned growth, however, can mean two different things. Assuming the temperature gradient is vertical, the growing crystal will either be parallel (z-crystal) or perpendicular (r-crystal) to this gradient. A crystal that lays horizontally can still grow in line with the temperature gradient, but it will mean growing on its face rather than its edge. Since the thermal conductivity of ice is so small (1.6 - 2.4 W mK) compared with most every other ceramic (ex. Al2O3= 40 W mK), the growing ice will have a significant insulative effect on the localized thermal conditions within the slurry. This can be illustrated using simple resistor elements.

When ice crystals are aligned with their basal planes parallel to the temperature gradient (z-crystals), they can be represented as two resistors in parallel. The thermal resistance of the ceramic is significantly smaller than that of the ice however, so the apparent resistance can be expressed as the lower Rceramic. If the ice crystals are aligned perpendicular to the temperature gradient (r-crystals), they can be approximated as two resistor elements in series. For this case, the Rice is limiting and will dictate the localized thermal conditions. The lower thermal resistance for the z-crystal case leads to lower temperatures and greater heat flux at the growing crystals tips, driving further growth in this direction while, at the same time, the large Rice value hinders the growth of the r-crystals. Each ice crystal growing within the slurry will be some combination of these two scenarios. Thermodynamics dictate that all crystals will tend to align with the preferential temperature gradient causing r-crystals to eventually give way to z-crystals, which can be seen from the following radiographs taken within the TZ.

When z-crystals become the only significant crystal orientation present, the ice-front grows in a steady-state manner except there are no significant changes to the system conditions. It was observed in 2012 that, in the initial moments of freezing, there are dendritic r-crystals that grow 5 - 15 times faster than the solidifying front. These shoot up into the suspension ahead of the main ice front and partially melt back. These crystals stop growing at the point where the TZ will eventually fully transition to the SSZ. Researchers determined that this particular point marks the position where the suspension is in an equilibrium state (i.e. freezing temperature and suspension temperature are equal). We can say then that the size of the initial and transition zones are controlled by the extent of supercooling beyond the already low freezing temperature. If the freeze-casting setup is controlled so that nucleation is favored at only small supercooling, then the TZ will give way to the SSZ sooner.

Steady-state growth zone

The structure in this final region contains long, aligned lamellae that alternate between ice crystals and ceramic walls. The faster a sample is frozen, the finer its solvent crystals (and its eventual macroporosity) will be. Within the SSZ, the normal speeds which are usable for colloidal templating are 10 – 100 mm s leading to solvent crystals typically between 2 mm and 200 mm. Subsequent sublimation of the ice within the SSZ yields a green ceramic preform with porosity in a nearly exact replica of these ice crystals. The microstructure of a freeze-cast within the SSZ is defined by its wavelength (λ) which is the average thickness of a single ceramic wall plus its adjacent macropore. Several publications have reported the effects of solidification kinetics on the microstructures of freeze-cast materials. It has been shown that λ follows an empirical power-law relationship with solidification velocity (υ) (Eq. 2.14):

Both A and υ are used as fitting parameters as currently there is no way of calculating them from first principles, although it is generally believed that A is related to slurry parameters like viscosity and solid loading while n is influenced by particle characteristics.

Controlling the porous structure

There are two general categories of tools for architecture a freeze-cast:

- Chemistry of the System - freezing medium and chosen particulate material(s), any additional binders, dispersants or additives.

- Operational Conditions - temperature profile, atmosphere, mold material, freezing surface, etc.

Initially, the materials system is chosen based on what sort of final structure is needed. This review has focused on water as the vehicle for freezing, but there are some other solvents that may be used. Notably, camphene, which is an organic solvent that is waxy at room temperature. Freezing of this solution produces highly branched dendritic crystals. Once the materials system is settled on however, the majority of microstructural control comes from external operational conditions such as mold material and temperature gradient.

Controlling pore size

The microstructural wavelength (average pore + wall thickness) can be described as a function of the solidification velocity v (λ= Av) where A is dependent on solids loading. There are two ways then that the pore size can be controlled. The first is to change the solidification speed that then alters the microstructural wavelength, or the solids loading can be changed. In doing so, the ratio of pore size to wall size is changed. It is often more prudent to alter the solidification velocity seeing as a minimum solid loading is usually desired. Since microstructural size (λ) is inversely related to the velocity of the freezing front, faster speeds lead to finer structures, while slower speeds produce a coarse microstructure. Controlling the solidification velocity is, therefore, crucial to being able to control the microstructure.

Controlling pore shape

Additives can prove highly useful and versatile in changing the morphology of pores. These work by affecting the growth kinetics and microstructure of the ice in addition to the topology of the ice-water interface. Some additives work by altering the phase diagram of the solvent. For example, water and NaCl have a eutectic phase diagram. When NaCl is added into a freeze-casting suspension, the solid ice phase and liquid regions are separated by a zone where both solids and liquids can coexist. This briny region is removed during sublimation, but its existence has a strong effect on the microstructure of the porous ceramic. Other additives work by either altering the interfacial surface energies between the solid/liquid and particle/liquid, changing the viscosity of the suspension, or the degree of undercooling in the system. Studies have been done with glycerol, sucrose, ethanol, acetic acid and more.

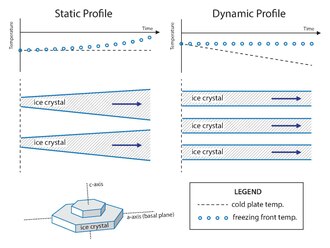

Static vs. dynamic freezing profiles

If a freeze casting setup with a constant temperature on either side of the freezing system is used, (static freeze-casting) the front solidification velocity in the SSZ will decrease over time due to the increasing thermal buffer caused by the growing ice front. When this occurs, more time is given for the anisotropic ice crystals to grow perpendicularly to the freezing direction (c-axis) resulting in a structure with ice lamellae that increase in thickness along the length of the sample.

To ensure highly anisotropic, yet predictable solidification behavior within the SSZ, dynamic freezing patterns are preferred. Using dynamic freezing, the velocity of the solidification front, and, therefore, the ice crystal size, can be controlled with a changing temperature gradient. The increasing thermal gradient counters the effect of the growing thermal buffer imposed by the growing ice front. It has been shown that a linearly decreasing temperature on one side of a freeze-cast will result in near-constant solidification velocity, yielding ice crystals with an almost constant thickness along the SSZ of an entire sample. However, as pointed out by Waschkies et al. even with constant solidification velocity, the thickness of the ice crystals does increase slightly over the course of freezing. In contrast to that, Flauder et al. demonstrated that an exponential change of the temperature at the cooling plate leads to a constant ice crystal thickness within the complete SSZ, which was attributed to a measurably constant ice-front velocity in a distinct study. This approach enables a prediction of the ice-front velocity from the thermal parameters of the suspension. Consequently, if the exact relationship between the pore diameter and ice-front velocity is known, an exact control over the pore diameter can be achieved.

Anisotropy of the interface kinetics

Even if the temperature gradient within the slurry is perfectly vertical, it is common to see tilting or curvature of the lamellae as they grow through the suspension. To explain this, it is possible to define two distinct growth directions for each ice crystal. There is the direction determined by the temperature gradient, and the one defined by the preferred growth direction crystallographically speaking. These angles are often at odds with one another, and their balance will describe the tilt of the crystal.

The non-overlapping growth directions also help to explain why dendritic textures are often seen in freeze-casts. This texturing is usually found only on the side of each lamella; the direction of the imposed temperature gradient. The ceramic structure left behind shows the negative image of these dendrites. In 2013, Deville et al. made the observation that the periodicity of these dendrites (tip-to-tip distance) actually seems to be related to the primary crystal thickness.

Particle packing effects

Up until now, the focus has been mostly on the structure of the ice itself; the particles are almost an afterthought to the templating process but in fact, the particles can and do play a significant role during freeze-casting. It turns out that particle arrangement also changes as a function of the freezing conditions. For example, researchers have shown that freezing velocity has a marked effect on wall roughness. Faster freezing rates produce rougher walls since particles are given insufficient time to rearrange. This could be of use when developing permeable gas transfer membranes where tortuosity and roughness could impede gas flow. It also turns out that z- and r-crystals do not interact with ceramic particles in the same way. The z-crystals pack particles in the x-y plane while r-crystals pack particles primarily in the z-direction. R-crystals actually pack particles more efficiently than z-crystals and because of this, the area fraction of the particle-rich phase (1 - area fraction of ice crystals) changes as the crystal population shifts from a mixture of z- and r-crystals to only z-crystals. Starting from where ice crystals first begin to exclude particles, marking the beginning of the transition zone, we have a majority of r-crystals and a high value for the particle-rich phase fraction. We can assume that because the solidification speed is still rapid that the particles will not be packed efficiently. As the solidification rate slows down, however, the area fraction of the particle-rich phase drops indicating an increase in packing efficiency. At the same time, the competitive growth process is taking place, replacing r-crystals with z-crystals. At a certain point nearing the end of the transition zone, the particle-rich phase fraction rises sharply since z-crystals are less efficient at packing particles than r-crystals. The apex of this curve marks the point where only z-crystals are present (SSZ). During steady-state growth, after the maximum particle-rich phase fraction is reached, the efficiency of packing increases as steady-state is achieved. In 2011, researchers at Yale University set out to probe the actual spatial packing of particles within the walls. Using small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) they characterized the particle size, shape and interparticle spacing of nominally 32 nm silica suspensions that had been freeze-cast at different speeds. Computer simulations indicated that for this system, the particles within the walls should not be touching but rather separated from one another by thin films of ice. Testing, however, revealed that the particles were, in fact, touching and more than that, they attained a packed morphology that cannot be explained by typical equilibrium densification processes.

Morphological instabilities

In an ideal world, the spatial concentration of particles within the SSZ would remain constant throughout solidification. As it happens, though, the concentration of particles does change during compression, and this process is highly sensitive to solidification speed. At low freezing rates, Brownian motion takes place, allowing particles to move easily away from the solid-liquid interface and maintain a homogeneous suspension. In this situation, the suspension is always warmer than the solidified portion. At fast solidification speeds, approaching VC, the concentration, and concentration gradient at the solid-liquid interface increases because particles cannot redistribute soon enough. When it has built up enough, the freezing point of the suspension is below the temperature gradient in the solution and morphological instabilities can occur. For situations where the particle concentration bleeds into the diffusion layer, both the actual and freezing temperature dip below the equilibrium freezing temperature creating an unstable system. Often, these situations lead to the formation of what are known as ice lenses.

These morphological instabilities can trap particles, preventing full redistribution and resulting in inhomogeneous distribution of solids along the freezing direction as well as discontinuities in the ceramic walls, creating voids larger than intrinsic pores within the walls of the porous ceramic.

Mechanical properties

Most research into the mechanical properties of freeze casted structures focus on the compressive strength of the material and its yielding behavior at increasing stresses. According to Ashby, the mechanical properties of a freeze-casted, open pore structure can be approximately modeled with an anisotropic, cellular solid. These include naturally occurring materials such as cork and wood that have properties that have anisotropic structures, and thus mechanical properties that are directionally dependent. Donius et al. have investigated the anisotropic nature of freeze-casted aerogels, comparing their mechanical strength to isotropically freeze casted aerogels. They found that the Young's modulus of the anisotropic structure was significantly higher than that of the isotropic aerogels, particularly when tested parallel to the freezing direction. The Young's modulus is several orders of magnitude higher in the parallel direction as compared to the direction perpendicular to freezing, demonstrating the anisotropic mechanical properties.

The mechanical behavior of the freeze casted structure can be classified into distinct regions. At low strains, the lamallae follow a linear elastic behavior. Here, the lamellae bend under a compressive stress, and thus deflect. According to Ashby, this deflection can be calculated from single beam theory, in which each of the cellular sections are idealized to be cubic shaped where each of the cell walls are assumed to me beam-like members with a square base. Based on this idealization, the amount of bending in the cell walls under a compressive force is given by where is the length of each cell, is the second moment of area, is the Young's modulus of the cell wall material and is a geometry dependent constant. Furthermore, we find that the Young's modulus of the entire structure is proportional to the square of the relative density: . This shows that the density of the material is an important factor when designing structures that can withstand loads, and that the Young's modulus of the structure is heavily determined by the porosity of the structure. Past the linear region, the lamellae start to buckle elastically and deform non-linearly. In a stress-strain curve, this is shown as a flat plateau. The critical load at which buckling begins is given by: where is a constant dependent on the boundary constraints of the structure. This is one of the main failure mechanisms for freeze casted materials. From this, the maximum compressive stress that an anisotropic porous solid can maintain is given by where is the fracture stress for the bulk material. These models demonstrate that the bulk material selection can drastically impact the mechanical response of freeze casted structures under stress. Other microstructural features such as the lamellar thickness, pore morphology and degree of macroporosity can also heavily influence the compressive strength and Young's modulus of these highly anisotropic structures.

Novel freeze-casting techniques

Freeze-casting can be applied to produce aligned porous structure from diverse building blocks including ceramics, polymers, biomacromolecules, graphene and carbon nanotubes. As long as there are particles that may be rejected by a progressing freezing front, a templated structure is possible. By controlling cooling gradients and the distribution of particles during freeze casting, using various physical means, the orientation of lamellae in obtained freeze cast structures can be controlled to provide improved performance in diverse applied materials. Munch et al. showed that it is possible to control the long-range arrangement and orientation of crystals normal to the growth direction by templating the nucleation surface. This technique works by providing lower energy nucleation sites to control the initial crystal growth and arrangement. The orientation of ice crystals can also be affected by applying electromagnetic fields as was demonstrated in 2010 by Tang et al. in 2012 by Porter et al., and in 2021 by Yin et al. Using specialized setups, researchers have been able to create radially aligned freeze-casts tailored for biomedical applications and filtration or gas separation applications. Inspired by nature, scientists have also been able to use coordinating chemicals and cryopreserved to create remarkably distinctive microstructural architectures.

Freeze cast materials

Particles that are assembled into aligned porous materials in freeze casting processes are often referred to as building blocks. As freeze casting has become a widespread technique the range of materials used has expanded. In recent years, graphene and carbon nanotubes have been used to fabricate controlled porous structures using freeze casting methods, with materials often exhibiting outstanding properties. Unlike aerogel materials produced without ice-templating, freeze cast structures of carbon nanomaterials have the advantage of possessing aligned pores, allowing, for example unparalleled combinations of low density and high conductivity.

Applications of freeze cast materials

Freeze casting is unique in its ability to produce aligned pore structures. Such structures are often found in nature, and consequently freeze casting has emerged as a valuable tool to fabricate biomimetic structures. The transport of fluids through aligned pores has led to the use of freeze casting as a method towards biomedical applications including bone scaffold materials. The alignment of pores in freeze cast structures also imparts extraordinarily high thermal resistance in the direction perpendicular to the aligned pores. The freeze casting of aligned porous fibres by spinning processes presents a promising method towards the fabrication of high performance insulating clothing articles.

See also

Further reading

- Lottermoser, A. (1908). "Uber das Ausfrieren von Hydrosolen". Chemische Berichte. 41 (3): 532–540. doi:10.1002/cber.19080410398.

- J. Laurie, Freeze Casting: a Modified Sol-Gel Process, University of Bath, UK, Ph.D. Thesis, 1995

- M. Statham, Economic Manufacture of Freeze-Cast Ceramic Substrate Shapes for the Spray-Forming Process, Univ. Bath, UK, Ph.D. Thesis, 1998

- S. Deville, "Freezing Colloids: Observations, Principles, Control, and Use." Springer, 2017

- Wegst, Ulrike G. K.; Kamm, Paul H.; Yin, Kaiyang; García-Moreno, Francisco (25 April 2024). "Freeze casting". Nature Reviews Methods Primers. 4 (1). doi:10.1038/s43586-024-00307-5.

External links

References

- Krauss Juillerat, Franziska (January 2011). "Microstructural Control of Self-Setting Particle-Stabilized Ceramic Foams". Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 94 (1): 77–83. doi:10.1111/j.1551-2916.2010.04040.x.

- ^ Greene, Eric S. (20 October 2006). "Mass transfer in graded microstructure solid oxide fuel cell electrodes". Journal of Power Sources. 161 (1): 225–231. Bibcode:2006JPS...161..225G. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2006.03.063.

- ^ Deville, Sylvain (April 2007). "Ice-templated porous alumina structures". Acta Materialia. 55 (6): 1965–1974. arXiv:1710.04651. Bibcode:2007AcMat..55.1965D. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2006.11.003. S2CID 119412656.

- ^ Deville, Sylvain (March 2008). "Freeze-Casting of Porous Ceramics: A Review of Current Achievements and Issues". Advanced Engineering Materials. 10 (3): 155–169. arXiv:1710.04201. doi:10.1002/adem.200700270. S2CID 51801964.

- Tong, Ho-ming; Noda, Isao; Gryte, Carl C. (July 1984). "CPS 768 Formation of anisotropic ice-agar composites by directional freezing". Colloid & Polymer Science. 262 (7): 589–595. doi:10.1007/BF01451524.

- Divakar, Prajan; Yin, Kaiyang; Wegst, Ulrike G.K. (February 2019). "Anisotropic freeze-cast collagen scaffolds for tissue regeneration: How processing conditions affect structure and properties in the dry and fully hydrated states". Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials. 90: 350–364. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2018.09.012. PMC 6777344. PMID 30399564.

- Weaver, Jordan S.; Kalidindi, Surya R.; Wegst, Ulrike G.K. (June 2017). "Structure-processing correlations and mechanical properties in freeze-cast Ti-6Al-4V with highly aligned porosity and a lightweight Ti-6Al-4V-PMMA composite with excellent energy absorption capability". Acta Materialia. 132: 182–192. Bibcode:2017AcMat.132..182W. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2017.02.031.

- Wegst, Ulrike G. K.; Kamm, Paul H.; Yin, Kaiyang; García-Moreno, Francisco (2024-04-25). "Freeze casting". Nature Reviews Methods Primers. 4 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1038/s43586-024-00307-5. ISSN 2662-8449.

- Hunger, Philipp M.; Donius, Amalie E.; Wegst, Ulrike G.K. (March 2013). "Platelets self-assemble into porous nacre during freeze casting". Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials. 19: 87–93. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2012.10.013. PMID 23313642.

- Yin, Kaiyang; Ji, Kaihua; Strutzenberg Littles, Louise; Trivedi, Rohit; Karma, Alain; Wegst, Ulrike G. K. (2023-06-06). "Hierarchical structure formation by crystal growth-front instabilities during ice templating". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 120 (23): e2210242120. Bibcode:2023PNAS..12010242Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.2210242120. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 10266019. PMID 37256929.

- Wegst, Ulrike G. K.; Bai, Hao; Saiz, Eduardo; Tomsia, Antoni P.; Ritchie, Robert O. (January 2015). "Bioinspired structural materials". Nature Materials. 14 (1): 23–36. Bibcode:2015NatMa..14...23W. doi:10.1038/nmat4089. ISSN 1476-1122. PMID 25344782.

- Lottermoser, A. (October–December 1908). "Über das Ausfrieren von Hydrosolen". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 41 (3): 3976–3979. doi:10.1002/cber.19080410398.

- Maxwell, W.A.; et al. (March 9, 1954). "Preliminary Investigation of the "Freeze-casting" Method for Forming Refractory Powders". National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics Collection Research Memorandum. The University of North Texas Libraries. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- Fukasawa Takayuki (2001). "Synthesis of Porous Ceramics with Complex Pore Structure by Freeze-Dry Processing". Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 84: 230–232. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.2001.tb00638.x.

- , Ice templating, freeze casting: Beyond materials processing

- Wegst, Ulrike G. K.; Schecter, Matthew; Donius, Amalie E.; Hunger, Philipp M. (2010). "Biomaterials by freeze casting". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 368 (1917): 2099–2121. Bibcode:2010RSPTA.368.2099W. doi:10.1098/rsta.2010.0014. ISSN 1364-503X. PMID 20308117.

- ^ Mallick, KK; Winnett, J; van Grunsven, W; Lapworth, J; Reilly, GC (2012). "Three-dimensional porous bioscaffolds for bone tissue regeneration: fabrication via adaptive foam reticulation and freeze casting techniques, characterization, and cell study". J Biomed Mater Res A. 100 (11): 2948–59. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.34238. PMID 22696264.

- Kim Jin-Woong (2009). "Honeycomb Monolith-Structured Silica with Highly Ordered, Three-Dimensionally Interconnected Macroporous Walls". Chemistry of Materials. 21 (15): 3476–3478. doi:10.1021/cm901265y.

- Wilde, G.; Perepezko, J.H. (2000). "Experimental study of particle incorporation during dendritic solidification". Materials Science and Engineering: A. 283 (1–2): 25–37. doi:10.1016/S0921-5093(00)00705-X.

- Archived 2015-05-22 at the Wayback Machine, Freeze Casting of High Strength Composites for Dental Applications

- Archived 2015-05-22 at the Wayback Machine, Dispersion, connectivity and tortuosity of hierarchical porosity composite SOFC cathodes prepared by freeze-casting

- ^ Archived 2015-05-22 at the Wayback Machine, Processing of Hierarchical and Anisotropic LSM-YSZ Ceramics

- , Lightweight and stiff cellular ceramic structures by ice templating

- Nguyen Phuong T. N. (2014). "Fast Dispersible Cocoa Tablets: A Case Study of Freeze-Casting Applied to Foods". Chemical Engineering & Technology. 37 (8): 1376–1382. doi:10.1002/ceat.201400032.

- Shao, Gaofeng; Hanaor, Dorian A. H.; Shen, Xiaodong; Gurlo, Aleksander (April 2020). "Freeze Casting: From Low-Dimensional Building Blocks to Aligned Porous Structures—A Review of Novel Materials, Methods, and Applications". Advanced Materials. 32 (17). Bibcode:2020AdM....3207176S. doi:10.1002/adma.201907176. ISSN 0935-9648.

- ^ Naglieri, Valentina; Bale, Hrishikesh A.; Gludovatz, Bernd; Tomsia, Antoni P.; Ritchie, Robert O. (2013). "On the development of ice-templated silicon carbide scaffolds for nature-inspired structural materials". Acta Materialia. 61 (18): 6948–6957. Bibcode:2013AcMat..61.6948N. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2013.08.006.

- ^ Waschkies, T.; Oberacker, R.; Hoffmann, M.J. (2011). "Investigation of structure formation during freeze-casting from very slow to very fast solidification velocities". Acta Materialia. 59 (13): 5135–5145. Bibcode:2011AcMat..59.5135W. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2011.04.046.

- ^ , Morphological instability in freezing colloidal suspensions

- ^ Deville Sylvain (2009). "In Situ X-Ray Radiography and Tomography Observations of the Solidification of Aqueous Alumina Particles Suspensions. Part II: Steady State". Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 92 (11): 2497–2503. arXiv:1710.04925. doi:10.1111/j.1551-2916.2009.03264.x. S2CID 51770415.

- ^ Soon, Young-Mi; Shin, Kwan-Ha; Koh, Young-Hag; Lee, Jong-Hoon; Kim, Hyoun-Ee (2009). "Compressive strength and processing of camphene-based freeze cast calcium phosphate scaffolds with aligned pores". Materials Letters. 63 (17): 1548–1550. Bibcode:2009MatL...63.1548S. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2009.04.013.

- Raymond JA, Wilson P, DeVries AL (February 1989). "Inhibition of growth of nonbasal planes in ice by fish antifreezes". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86 (3): 881–5. Bibcode:1989PNAS...86..881R. doi:10.1073/pnas.86.3.881. PMC 286582. PMID 2915983.

- ^ Peppin, S. S. L.; Wettlaufer, J. S.; Worster, M. G. (2008). "Experimental Verification of Morphological Instability in Freezing Aqueous Colloidal Suspensions". Physical Review Letters. 100 (23): 238301. Bibcode:2008PhRvL.100w8301P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.238301. PMID 18643549. S2CID 34546082.

- Bareggi Andrea (2011). "Dynamics of the Freezing Front During the Solidification of a Colloidal Alumina Aqueous Suspension:In Situ X-Ray Radiography, Tomography, and Modeling". Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 94 (10): 3570–3578. arXiv:1804.00046. doi:10.1111/j.1551-2916.2011.04572.x. S2CID 51777635.

- ^ Lasalle Audrey (2011). "Ice-Templating of Alumina Suspensions: Effect of Supercooling and Crystal Growth During the Initial Freezing Regime". Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 95 (2): 799–804. arXiv:1804.08700. doi:10.1111/j.1551-2916.2011.04993.x. S2CID 51783680.

- ^ "Recent trends in shape forming from colloidal processing: A review". Archived from the original on 2015-05-22. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Deville Sylvain (2010). "Influence of Particle Size on Ice Nucleation and Growth During the Ice-Templating Process". Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 93 (9): 2507–2510. arXiv:1805.01354. doi:10.1111/j.1551-2916.2010.03840.x. S2CID 51851812.

- Han, Jiecai; Hong, Changqing; Zhang, Xinghong; Du, Jiancong; Zhang, Wei (2010). "Highly porous ZrO2 ceramics fabricated by a camphene-based freeze-casting route: Microstructure and properties". Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 30: 53–60. doi:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2009.08.018.

- ^ Waschkies Thomas (2009). "Control of Lamellae Spacing During Freeze Casting of Ceramics Using Double-Side Cooling as a Novel Processing Route". Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 92: S79–S84. doi:10.1111/j.1551-2916.2008.02673.x.

- ^ Flauder, Stefan; Gbureck, Uwe; Müller, Frank A. (December 2014). "Structure and mechanical properties of β-TCP scaffolds prepared by ice-templating with preset ice front velocities". Acta Biomaterialia. 10 (12): 5148–5155. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2014.08.020. PMID 25159370.

- ^ Stolze, Christian; Janoschka, Tobias; Schubert, Ulrich S.; Müller, Frank A.; Flauder, Stefan (January 2016). "Directional Solidification with Constant Ice Front Velocity in the Ice-Templating Process: Directional Solidification with Constant Ice Front Velocity". Advanced Engineering Materials. 18 (1): 111–120. doi:10.1002/adem.201500235. S2CID 135858128.

- ^ Munch Etienne (2009). "Architectural Control of Freeze-Cast Ceramics Through Additives and Templating". Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 92 (7): 1534–1539. arXiv:1710.04095. doi:10.1111/j.1551-2916.2009.03087.x. S2CID 51808968.

- ^ Deville Sylvain (2012). "Ice-Structuring Mechanism for Zirconium Acetate". Langmuir. 28 (42): 14892–14898. arXiv:1804.00045. doi:10.1021/la302275d. PMID 22880966. S2CID 9156160.

- Deville, S.; Adrien, J.; Maire, E.; Scheel, M.; Di Michiel, M. (2013). "Time-lapse, three-dimensional in situ imaging of ice crystal growth in a colloidal silica suspension". Acta Materialia. 61 (6): 2077–2086. arXiv:1805.05415. Bibcode:2013AcMat..61.2077D. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2012.12.027. S2CID 51774647.

- Farhangdoust, S.; Zamanian, A.; Yasaei, M.; Khorami, M. (2013). "The effect of processing parameters and solid concentration on the mechanical and microstructural properties of freeze-casted macroporous hydroxyapatite scaffolds". Materials Science and Engineering: C. 33 (1): 453–460. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2012.09.013. PMID 25428095.

- ^ , Particle-scale structure in frozen colloidal suspensions from small angle x-ray scattering

- Lasalle, Audrey; Guizard, Christian; Maire, Eric; Adrien, Jérôme; Deville, Sylvain (2012). "Particle redistribution and structural defect development during ice templating". Acta Materialia. 60 (11): 4594–4603. arXiv:1804.08699. Bibcode:2012AcMat..60.4594L. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2012.02.023. S2CID 53008016.

- ^ Ashby, M. F.; Medalist, R. F. Mehl (1983-09-01). "The mechanical properties of cellular solids". Metallurgical Transactions A. 14 (9): 1755–1769. Bibcode:1983MTA....14.1755A. doi:10.1007/BF02645546. ISSN 2379-0180.

- Donius, Amalie E.; Liu, Andong; Berglund, Lars A.; Wegst, Ulrike G.K. (September 2014). "Superior mechanical performance of highly porous, anisotropic nanocellulose–montmorillonite aerogels prepared by freeze casting". Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials. 37: 88–99. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2014.05.012. ISSN 1751-6161. PMID 24905177.

- ^ Ojuva, Arto; Järveläinen, Matti; Bauer, Marcus; Keskinen, Lassi; Valkonen, Masi; Akhtar, Farid; Levänen, Erkki; Bergström, Lennart (September 2015). "Mechanical performance and CO2 uptake of ion-exchanged zeolite A structured by freeze-casting". Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 35 (9): 2607–2618. doi:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2015.03.001. ISSN 0955-2219.

- ^ Porter, Michael M.; Imperio, Russ; Wen, Matthew; Meyers, Marc A.; McKittrick, Joanna (April 2014). "Bioinspired Scaffolds with Varying Pore Architectures and Mechanical Properties". Advanced Functional Materials. 24 (14): 1978–1987. doi:10.1002/adfm.201302958. ISSN 1616-301X.

- Zhang, J.; Ashby, M. F. (1992-06-01). "The out-of-plane properties of honeycombs". International Journal of Mechanical Sciences. 34 (6): 475–489. doi:10.1016/0020-7403(92)90013-7. ISSN 0020-7403.

- Shao, Gaofeng; Hanaor, Dorian A. H.; Shen, Xiaodong; Gurlo, Aleksander (2020). "Freeze Casting: From Low‐Dimensional Building Blocks to Aligned Porous Structures—A Review of Novel Materials, Methods, and Applications". Advanced Materials. 32 (17). doi:10.1002/adma.201907176. ISSN 0935-9648.

- Shao, Gaofeng; Hanaor, Dorian A. H.; Shen, Xiaodong; Gurlo, Aleksander (2020). "Freeze Casting: From Low‐Dimensional Building Blocks to Aligned Porous Structures—A Review of Novel Materials, Methods, and Applications". Advanced Materials. 32 (17). 3.5 Polymer and Biomacromolecule as Building Blocks. doi:10.1002/adma.201907176. ISSN 0935-9648.

- Shao, G (2020). "Freeze Casting: From Low-Dimensional Building Blocks to Aligned Porous Structures—A Review of Novel Materials, Methods, and Applications". Advanced Materials. 32 (17): 1907176. Bibcode:2020AdM....3207176S. doi:10.1002/adma.201907176. PMID 32163660.

- Tang, Y.F.; Zhao, K.; Wei, J.Q.; Qin, Y.S. (2010). "Fabrication of aligned lamellar porous alumina using directional solidification of aqueous slurries with an applied electrostatic field". Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 30 (9): 1963–1965. doi:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2010.03.012.

- Porter, Michael M.; Yeh, Michael; Strawson, James; Goehring, Thomas; Lujan, Samuel; Siripasopsotorn, Philip; Meyers, Marc A.; McKittrick, Joanna (October 2012). "Magnetic freeze casting inspired by nature". Materials Science and Engineering: A. 556: 741–750. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2012.07.058.

- Yin, Kaiyang; Reese, Bradley A.; Sullivan, Charles R.; Wegst, Ulrike G. K. (February 2021). "Superior Mechanical and Magnetic Performance of Highly Anisotropic Sendust-Flake Composites Freeze Cast in a Uniform Magnetic Field". Advanced Functional Materials. 31 (8). doi:10.1002/adfm.202007743.

- Yin, Kaiyang; Mylo, Max D.; Speck, Thomas; Wegst, Ulrike G.K. (October 2020). "Bamboo-inspired tubular scaffolds with functional gradients". Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials. 110: 103826. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2020.103826. PMID 32957175.

- Yin, Kaiyang; Divakar, Prajan; Wegst, Ulrike G.K. (January 2019). "Freeze-casting porous chitosan ureteral stents for improved drainage". Acta Biomaterialia. 84: 231–241. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2018.11.005. PMC 6864386. PMID 30414484.

- Moon, Ji-Woong; Hwang, Hae-Jin; Awano, Masanobu; Maeda, Kunihiro (2003). "Preparation of NiO–YSZ tubular support with radially aligned pore channels". Materials Letters. 57 (8): 1428–1434. Bibcode:2003MatL...57.1428M. doi:10.1016/S0167-577X(02)01002-9.

- Shao, Yuanlong; El-Kady, Maher F.; Lin, Cheng-Wei; Zhu, Guanzhou; Marsh, Kristofer L.; Hwang, Jee Youn; Zhang, Qinghong; Li, Yaogang; Wang, Hongzhi; Kaner, Richard B. (2016). "3D Freeze-Casting of Cellular Graphene Films for Ultrahigh-Power-Density Supercapacitors". Advanced Materials. 28 (31): 6719–6726. Bibcode:2016AdM....28.6719S. doi:10.1002/adma.201506157. PMID 27214752.

- Chemical vapor infiltration tailored hierarchical porous CNTs/C composite spheres fabricated by freeze casting and their adsorption properties

- Deville, Sylvain; Saiz, Eduardo; Tomsia, Antoni P. (2006). "Freeze casting of hydroxyapatite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering". Biomaterials. 27 (32): 5480–5489. arXiv:1710.04392. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.06.028. PMID 16857254. S2CID 2910118.

. The transition from a porous R (lamellar) morphology to one where the majority of particles are entrapped occurs at vc, which is generally determined as:

. The transition from a porous R (lamellar) morphology to one where the majority of particles are entrapped occurs at vc, which is generally determined as:

in the cell walls under a compressive force

in the cell walls under a compressive force  is given by

is given by  where

where  is the length of each cell,

is the length of each cell,  is the second moment of area,

is the second moment of area,  is the Young's modulus of the cell wall material and

is the Young's modulus of the cell wall material and  is a geometry dependent constant. Furthermore, we find that the Young's modulus of the entire structure

is a geometry dependent constant. Furthermore, we find that the Young's modulus of the entire structure  is proportional to the square of the relative density:

is proportional to the square of the relative density:  . This shows that the density of the material is an important factor when designing structures that can withstand loads, and that the Young's modulus of the structure is heavily determined by the porosity of the structure. Past the linear region, the lamellae start to buckle elastically and deform non-linearly. In a stress-strain curve, this is shown as a flat plateau. The critical load at which buckling begins is given by:

. This shows that the density of the material is an important factor when designing structures that can withstand loads, and that the Young's modulus of the structure is heavily determined by the porosity of the structure. Past the linear region, the lamellae start to buckle elastically and deform non-linearly. In a stress-strain curve, this is shown as a flat plateau. The critical load at which buckling begins is given by:  where

where  is a constant dependent on the boundary constraints of the structure. This is one of the main failure mechanisms for freeze casted materials. From this, the maximum compressive stress that an anisotropic porous solid can maintain is given by

is a constant dependent on the boundary constraints of the structure. This is one of the main failure mechanisms for freeze casted materials. From this, the maximum compressive stress that an anisotropic porous solid can maintain is given by  where

where  is the

is the