| George Kistiakowsky | |

|---|---|

George Kistiakowsky George Kistiakowsky | |

| Born | December 1 [O.S. November 18] 1900 Boiarka, Russian Empire (now Ukraine) |

| Died | December 7, 1982(1982-12-07) (aged 82) Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States |

| Nationality | Ukrainian-American |

| Citizenship | American |

| Alma mater | University of Berlin |

| Known for | |

| Awards | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physical chemistry |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral advisor | Max Bodenstein |

| Doctoral students | |

| Signature | |

| |

George Bogdanovich Kistiakowsky (Russian: Георгий Богданович Кистяковский, Ukrainian: Георгій Богданович Кістяківський, romanized: Heorhii Bohdanovych Kistiakivskyi; December 1 [O.S. November 18] 1900 – December 7, 1982) was a Ukrainian-American physical chemistry professor at Harvard who participated in the Manhattan Project and later served as President Dwight D. Eisenhower's Science Advisor.

Born in Boyarka in the old Russian Empire, into "an old Ukrainian Cossack family which was part of the intellectual elite in pre-revolutionary Russia", Kistiakowsky fled his homeland during the Russian Civil War. He made his way to Germany, where he earned his PhD in physical chemistry under the supervision of Max Bodenstein at the University of Berlin. He emigrated to the United States in 1926, where he joined the faculty of Harvard University in 1930, and became a citizen in 1933.

During World War II, Kistiakowsky was the head of the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) section responsible for the development of explosives, and the technical director of the Explosives Research Laboratory (ERL), where he oversaw the development of new explosives, including RDX and HMX. He was involved in research into the hydrodynamic theory of explosions, and the development of shaped charges. In October 1943, he was brought into the Manhattan Project as a consultant. He was soon placed in charge of X Division, which was responsible for the development of the explosive lenses necessary for an implosion-type nuclear weapon. In July 1945, he watched the first atomic explosion in the Trinity test. A few weeks later, another implosion-type weapon (Fat Man) was dropped on Nagasaki.

From 1962 to 1965, Kistiakowsky chaired the National Academy of Sciences's Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy (COSEPUP), and was its vice president from 1965 to 1973. He severed his connections with the government in protest against the war in Vietnam, and became active in an antiwar organization, the Council for a Livable World, becoming its chairman in 1977.

Early life

George Bogdanovich Kistiakowsky was born in Boyarka, in the Kyiv Governorate of the Russian Empire (now part of Ukraine), on December 1 [O.S. November 18] 1900. George's grandfather Aleksandr Fedorovych Kistiakovsky was a professor of law and an attorney of the Russian Empire who specialized in criminal law. His father Bogdan Kistiakovsky was a professor of legal philosophy at the University of Kyiv, and was elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine in 1919. Kistiakowsky's mother was Maria Berendshtam, and he had a brother, Alexander who became an ornithologist. George's uncle Ihor Kistiakovsky was the Minister of Internal Affairs of the Ukrainian State.

Kistiakowsky attended private schools in Kyiv and Moscow until the Russian Revolution broke out in 1917. He then joined the anti-Communist White Army. In 1920 he escaped from Russia in a commandeered French ship. After spending time in Turkey and Yugoslavia, he made his way to Germany, where he enrolled at the University of Berlin later that year. In 1925, he earned his PhD in physical chemistry under the supervision of Max Bodenstein, writing his thesis on the photochemical decomposition of chlorine monoxide and ozone. He then became Bodenstein's graduate assistant. His first two published papers were elaborations of his thesis, co-written with Bodenstein.

In 1926, Kistiakowsky traveled to the United States as an International Education Board fellow. Hugh Stott Taylor, another student of Bodenstein, accepted Bodenstein's assessment of Kistiakowsky, and gave him a place at Princeton University. That year, Kistiakowsky married a Swedish Lutheran woman, Hildegard Moebius. In 1928, they had a daughter, Vera, who, in 1972 became the first woman appointed as a professor of physics at MIT. When Kistiakowsky's two-year fellowship ran out in 1927, he received a research associate and DuPont Fellowship. On October 25, 1928, he became an associate professor at Princeton. Taylor and Kistiakowsky published a series of papers together. Encouraged by Taylor, Kistiakowsky also published an American Chemical Society monograph on photochemical processes.

In 1930, Kistiakowsky joined the faculty of Harvard University, an affiliation that continued throughout his career. At Harvard, his research interests were in thermodynamics, spectroscopy, and chemical kinetics. He became increasingly involved in consulting for the government and industry. He became an associate professor again, this time at Harvard in 1933. That year he also became an American citizen and was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1938, he became the Abbott and James Lawrence Professor of Chemistry. He was elected to the United States National Academy of Sciences the following year. In 1940, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society.

World War II

National Defense Research Committee

Foreseeing an expanded role for science in World War II, which the United States had not yet joined, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) on June 27, 1940, with Vannevar Bush as its chairman. James B. Conant, the President of Harvard, was appointed head of Division B, which was responsible for bombs, fuels, gases, and chemicals. He appointed Kistiakowsky to head its Section A-1, which was concerned with explosives. In June 1941, the NDRC was absorbed into the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD). Bush became chairman of the OSRD, Conant succeeded him as chairman of the NDRC, and Kistiakowsky became head of Section B. In a reorganization in December 1942, Division B was broken up, and he became head of Division 8, which was responsible for explosives and propellants, remaining in this position until February 1944.

Kistiakowsky was unhappy with the state of American knowledge of explosives and propellants. Conant established the Explosives Research Laboratory (ERL) near the laboratories of the Bureau of Mines in Bruceton, Pennsylvania in October 1940, and Kistiakowsky initially supervised its activities, making occasional visits; but Conant did not formally appoint him as its technical director until the spring of 1941. Although initially hampered by a shortage of facilities, the ERL grew from five staff in 1941 to a wartime peak of 162 full-time laboratory staff in 1945. An important field of research was RDX. This powerful explosive had been developed by the Germans before the war. The challenge was to develop an industrial process that could produce it on a large scale. RDX was also mixed with TNT to produce Composition B, which was widely used in various munitions, and torpex, which was used in torpedoes and depth charges. Pilot plants were in operation by May 1942, and large-scale production followed in 1943.

In response to a special request for an explosive that could be smuggled through Japanese checkpoints by Chinese guerrillas, Kistakowsky mixed HMX, a non-toxic explosive produced as a by-product of the RDX process, with flour to create "Aunt Jemima", after a brand of pancake flour. This was an edible explosive, which could pass for regular flour, and even be used in cooking.

In addition to research into synthetic explosives like RDX and HMX, the ERL investigated the properties of detonations and shock waves. This was initiated as a pure research project, without obvious or immediate applications. Kistiakowsky visited England in 1941 and again in 1942, where he met with British experts, including William Penney and Geoffrey Taylor. When Kistiakowsky and Edgar Bright Wilson, Jr., surveyed the existing state of knowledge, they found several areas that warranted further investigation. Kistiakowsky began to look into the Chapman–Jouguet model, which describes the way the shock wave created by a detonation propagates.

At this time, the efficacy of the Chapman–Jouguet model was still in doubt, and it was the subject of studies by John von Neumann at the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study. Kistiakowsky realized that the deviations from hydrodynamic theory were the result of the speed of the chemical reactions themselves. To control the reaction, calculations down to the microsecond level were needed. Section 8 was drawn into the investigation of shaped charges, whose mechanism was explained by Taylor and James Tuck in 1943.

Manhattan Project

At the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory, research into implosion had been proceeding under Seth Neddermeyer, but his division had worked with cylinders and small charges, and had produced only objects that looked like rocks. Their research was accorded a low priority, owing to expectations that a gun-type nuclear weapon design would work for both uranium-235 and plutonium, and implosion technology would not be required.

In September 1943, the Los Alamos Laboratory's director, Robert Oppenheimer, arranged for von Neumann to visit Los Alamos and investigate implosion with a fresh set of eyes. After reviewing Neddermeyer's studies, and discussing the matter with Edward Teller, von Neumann suggested the use of high explosive in shaped charges to implode a sphere, which he showed could not only result in a faster assembly of fissile material than was possible with the gun method, but greatly reduce the amount of material required. The prospect of more efficient nuclear weapons impressed Oppenheimer, Teller and Hans Bethe, but they decided that an expert on explosives was required. Kistiakowsky's name was immediately suggested, and he was brought into the project as a consultant in October 1943.

Kistiakowsky was initially reluctant to come, "partly because", he later explained, "I didn't think the bomb would be ready in time and I was interested in helping to win the war". At Los Alamos, he began reorganizing the implosion effort. He introduced techniques such as photography and X-rays to study the behavior of shaped charges. The former had been extensively employed by the ERL, while the latter had been described in papers by Tuck, who also suggested using three-dimensional explosive lenses. As with other aspects of the Manhattan Project, research into explosive lenses followed multiple lines of inquiry simultaneously because, as Kistiakowsky noted, it was "impossible to predict which of these basic techniques will be the more successful."

Kistiakowsky brought with him to Los Alamos a detailed knowledge of all the studies into shaped charges, of explosives like Composition B, and of the procedures used at the ERL in 1942 and 1943. Increasingly, the ERL itself would be drawn into the implosion effort; its deputy director Duncan MacDougall also took charge of the Manhattan Project's Project Q. Kistiakowsky replaced Neddermeyer as head of E (for explosives) Division in February 1944.

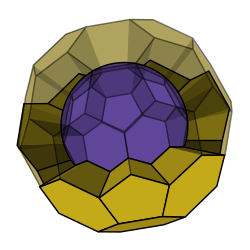

The implosion program acquired a new urgency after Emilio Segrè's group at Los Alamos verified that plutonium produced in the nuclear reactors contained plutonium-240, which made it unsuitable for use in a gun-type weapon. A series of crisis meetings in July 1944 concluded that the only prospect for a working plutonium weapon was implosion. In August, Oppenheimer reorganized the entire laboratory to concentrate on it. A new explosives group, X Division, was created under Kistiakowsky to develop the lenses.

Under Kistiakowsky's leadership, X-Division designed the complex explosive lenses needed to compress the fissile plutonium pit. These employed two explosives with significantly different velocities of detonation in order to produce the required waveform. Kistiakowsky chose Baratol for the slow explosive. After experimenting with various fast explosives, X-Division settled on Composition B. Work on molding the explosives into the right shape continued into 1945. The lenses needed to be flawless, and techniques for casting Composition B and Baratol had to be developed. The ERL managed to accomplish this by devising a procedure for preparing Baratol in a form that was easy to cast. In March 1945, Kistiakowsky became part of the Cowpuncher Committee, so-called because it rode herd on the implosion effort. On July 16, 1945, Kistiakowsky watched as the first device was detonated in the Trinity test. A few weeks later, a Fat Man implosion-type nuclear weapon was dropped on Nagasaki.

Along with his work on implosion, Kistiakowsky contributed to skiing in Los Alamos by using rings of explosives to fell trees for a ski slope — leading to the establishment of Sawyer's Hill Ski Tow Association. He divorced Hildegard in 1942 and married Irma E. Shuler in 1945. They were divorced in 1962, and he married Elaine Mahoney.

White House service

In 1957, during the Eisenhower Administration, Kistiakowsky was appointed to the President's Science Advisory Committee, and succeeded James R. Killian as chairman in 1959. He directed the Office of Science and Technology Policy from 1959 to 1961, when he was succeeded by Jerome B. Wiesner.

In 1958, Kistiakowsky suggested to President Eisenhower that inspection of foreign military facilities was not sufficient to control their nuclear weapons. He cited the difficulty in monitoring missile submarines, and proposed that the arms control strategy focus on disarmament rather than inspections. In January 1960, as part of arms control planning and negotiation, he suggested the "threshold concept". Under this proposal, all nuclear tests above the level of seismic detection technology would be forbidden. After such an agreement, the US and USSR would work jointly to improve detection technology, revising the permissible test yield downward as techniques improved. This example of the "national means of technical verification", a euphemism for sensitive intelligence collection used in arms control, would provide safeguards, without raising the on-site inspection requirement to a level unacceptable to the Soviets. The US introduced the threshold concept to the Soviets at the Geneva arms control conference in January 1960 and the Soviets, in March, responded favorably, suggesting a threshold of a given seismic magnitude. Talks broke down as a result of the U-2 Crisis of 1960 in May.

At the same time as the early nuclear arms control work, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Nathan F. Twining, sent a memorandum, in August 1959, to the Secretary of Defense, Neil McElroy, which suggested that the Strategic Air Command (SAC) formally be assigned responsibility to prepare the national nuclear target list, and a single plan for nuclear operations. Up to that point, the Army, Navy, and Air Force had done their own target planning. This had led to the same objectives being targeted multiple times by the different services. The separate service plans were not mutually supporting as in, for example, the Navy destroying an air defense facility on the route of an Air Force bomber going to a deeper target. While Twining had sent the memo to McElroy, the members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff disagreed on the policy during early 1960. Thomas Gates, who succeeded McElroy, asked President Dwight D. Eisenhower to decide the policy.

Eisenhower said he would not "leave his successor with the monstrosity" of the uncoordinated and un-integrated forces that then existed. In early November 1960, he sent Kistiakowsky to SAC Headquarters in Omaha to evaluate its war plans. Initially, Kistiakowsky was not given access, and Eisenhower sent him back, with a much stronger set of orders for SAC officers to cooperate. Kistiakowsky's report, presented on November 29, described uncoordinated plans with huge numbers of targets, many of which would be attacked by multiple forces, resulting in overkill. Eisenhower was shocked by the plans, and focused not just on the creation of the Single Integrated Operational Plan (SIOP), but on the entire process of picking targets, generating requirements, and planning for nuclear war operations.

Later life

Between his work for the Manhattan Project and his White House service, and again after he left the White House, Kistiakowsky was a professor of physical chemistry at Harvard. When asked to teach a freshman class in 1957, he turned to Hubert Alyea, whose lecture style had impressed him. Alyea sent him some 700 4-by-6-inch (10.2 by 15.2 cm) index cards containing details of lecture demonstrations. Aside from the cards, Kistiakowsky never prepared the demonstrations. He later recalled:

I didn't think that was giving mother Nature a sporting chance. I would come into the lecture hall, glance at the chemicals and pile of cards and announce to the students "let's see what Alyea has for us today". I never used a text book, only your cards. I would glance at the instructions and carry out the experiment. If it worked we would bless you and pass on to the next demonstration. If it didn't work we would curse you, and spend the rest of the lecture trying to make it work.

He retired from Harvard as professor emeritus in 1972.

From 1962 to 1965, Kistiakowsky chaired the National Academy of Science's Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy (COSEPUP), and was its vice president from 1965 to 1973. He received several awards over the years, including the Department of the Air Force Decoration for Exceptional Civilian Service in 1957. He was awarded the Medal for Merit by President Truman, the Medal of Freedom by President Eisenhower in 1961, and the National Medal of Science by President Lyndon Johnson in 1967. He was also a recipient the Charles Lathrop Parsons Award for public service from the American Chemical Society in 1961, Priestley Medal from the American Chemical Society in 1972, and the Franklin Medal from Harvard.

In later years, Kistiakowsky was active in an antiwar organization, the Council for a Livable World. He severed his connections with the government in protest against the US involvement in the Vietnam War. In 1977, he assumed the chairmanship of the council, campaigning against nuclear proliferation. He died of cancer in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on December 17, 1982. His body was cremated, and his ashes scattered near his summer home on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. His papers are in the Harvard University archives. He is also memorialized by a redwood grove in Montgomery Woods State Natural Reserve in California.

Notes

- ^ Кучеренко, Микола (2006). "Будинок Кістяківських у Боярці". Український археографічний щорічник. 10/11: 856.

- The Ukrainian Review, v. 7 (1959), p. 125

- Запис про народження 18 листопада (ст. ст.) 1900 року Георгія Кістяківського в метричній книзі церкви Успіння Пресвятої Богородиці села Боярка Київського повіту // ЦДІАК України. Ф. 127. Оп. 1078. Спр. 2220. Арк. 180зв–181. (ru) (uk)

- ^ Dainton 1985, pp. 379–380.

- Heuman 1998, pp. 7–8, 213.

- ^ Heuman 1998, pp. 37–38.

- ^ "Kistiakowsky, George B. (George Bogdan), 1900– Papers of George B. Kistiakowsky : an inventory". Harvard University. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- ^ Dainton 1985, p. 401.

- "Chemistry Tree — Max Ernst August Bodenstein Family Tree". Chemistry Tree. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- "Vera Kistiakowsky's Interview | Manhattan Project Voices".

- Vera Kistiakowsky Papers, MC 485 Archived 2019-07-01 at the Wayback Machine, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Institute Archives and Special Collections, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- "George Bogdan Kistiakowsky". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. 9 February 2023. Retrieved 2023-05-03.

- ^ Dainton 1985, p. 382.

- "George B. Kistiakowsky". www.nasonline.org. Retrieved 2023-05-03.

- "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2023-05-03.

- Stewart 1948, p. 7.

- Stewart 1948, p. 10.

- Stewart 1948, pp. 52–54.

- Stewart 1948, p. 88.

- Dainton 1985, p. 383.

- Noyes 1948, p. 25.

- Noyes 1948, p. 27.

- Noyes 1948, p. 28.

- Noyes 1948, pp. 36–42.

- Clode, George (June 12, 2012). "Back to the Drawing Board – Aunt Jemima". Military History Monthly. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- Noyes 1948, p. 51.

- ^ Noyes 1948, pp. 58–64.

- Chapman, David Leonard (January 1899). "On the Rate of Explosion in Gases". Philosophical Magazine. Series 5. 47 (284). London: 90–104. doi:10.1080/14786449908621243. ISSN 1941-5982. LCCN sn86025845.

- Noyes 1948, p. 73.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 130–133.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 137.

- Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 166.

- Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 236–240.

- Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 241–247.

- Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 294–299.

- Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 316.

- Dainton 1985, p. 384.

- Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 394–396.

- Gibson, Michnovicz & Michnovicz 2005, p. 78.

- ^ Biography for George Kistiakowsky at IMDb. Accessed May 10, 2013

- "Previous Science Advisors". Office of Science and Technology Policy. Archived from the original on January 22, 2017. Retrieved May 10, 2013..

- "Space Policy Project (summary of Foreign Relations of the US, text not online)". Foreign Relations of the United States 1958–1960. National Security Policy, Arms Control and Disarmament, Volume III. Washington, DC: US Department of State (summary by Federation of American Scientists). 1961. FRUS58. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05.

- Burr, William; Montford, Hector L. (eds.). "The Making of the Limited Test Ban Treaty, 1958–1963". George Washington University. Retrieved May 10, 2013.

- Twining, Nathan F. (20 August 1959). "Document 2: J.C.S. 2056/131, Notes by the Secretaries to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, enclosing memorandum from JCS Chairman Nathan Twining to Secretary of Defense, "Target Coordination and Associated Problems,"" (PDF). The Creation of SIOP-62: More Evidence on the Origins of Overkill National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 130. George Washington University National Security Archive. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- Twining, Nathan F. (5 October 1959). "Document 3A: JCS 2056/143, Note by the Secretaries to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 5 October 1959, enclosing Memorandum for the Joint Chiefs of Staff, "Target Coordination and Associated Problems,"" (PDF). The Creation of SIOP-62: More Evidence on the Origins of Overkill National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 130. George Washington University National Security Archive. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- Burke, Arleigh (30 September 1959). "Document 3B: attached memorandum from Chief of Naval Operations" (PDF). The Creation of SIOP-62: More Evidence on the Origins of Overkill National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 130. George Washington University National Security Archive. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- McKinzie, Matthew G.; Cochran, Thomas B.; Norris, Robert S.; Arkin, William M. (2001). The U.S. Nuclear War Plan: A Time for Change (PDF) (Report). Vol. Chapter Two: The Single Integrated Operational Plan and U.S. Nuclear Forces. National Resources Defense Council.

- Burr, William (ed.). "The Creation of SIOP-62 More Evidence on the Origins of Overkill". George Washington University. Retrieved May 10, 2013.

- ^ "George B. Kistiakowsky". Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- "Origins of COSEPUP". National Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on April 23, 2007. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- Dainton 1985, p. 386.

- "Charles Lathrop Parsons Award". American Chemical Society. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- Dainton 1985, p. 400.

- ^ Rathjens, George (April 1983). "George B. Kistiakowsky (1900–1982)". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 39 (4): 2–3. Bibcode:1983BuAtS..39d...2R. doi:10.1080/00963402.1983.11458970. Retrieved May 10, 2013.

- "George B. Kistiakowsky Dies; Helped Develop Atomic Bomb". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. December 12, 1982. p. 22]. Retrieved April 7, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Kistiakowsky, George B. (George Bogdan), 1900– Papers of George B. Kistiakowsky: an inventory. Harvard University Archives". Harvard University. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

References

- Dainton, F. (1985). "George Bogdan Kistiakowsky. 18 November 1900-7 December 1982". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 31: 376–408. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1985.0013. JSTOR 769930. S2CID 71285501.

- Gibson, Toni Michnovicz; Michnovicz, Jon & Michnovicz, John (2005). Los Alamos: 1944–1947. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia. ISBN 978-0-7385-2973-8. OCLC 59715051.

- Heuman, Susan Eva (1998). Kistiakovsky: The Struggle for National and Constitutional Rights in the Last Years of Tsarism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Distributed by Harvard University Press for the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. ISBN 978-0-916458-61-4. OCLC 38853810.

- Hoddeson, Lillian; Henriksen, Paul W.; Meade, Roger A. & Westfall, Catherine L. (1993). Critical Assembly: A Technical History of Los Alamos During the Oppenheimer Years, 1943–1945. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44132-3. OCLC 26764320.

- Noyes, W. Albert, ed. (1948). Chemistry, a History of the Chemistry Components of the National Defense Research Committee, 1940–1946. Science in World War II; Office of Scientific Research and Development. Boston: Little, Brown. hdl:2027/mdp.39015014208352. OCLC 14669626. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- Stewart, Irvin (1948). Organizing Scientific Research for War: The Administrative History of the Office of Scientific Research and Development. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. OCLC 500138898. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

Further reading

- Lawrence Badash, J.O. Hirschfelder & H.P. Broida, eds., Reminiscences of Los Alamos 1943–1945 (Studies in the History of Modern Science), Springer, 1980, ISBN 90-277-1098-8.

- Confessions of a Weaponeer, PBS Nova, with Carl Sagan pbs.org

External links

- 1982 Audio Interview with George Kistiakowsky by Richard Rhodes at Voices of the Manhattan Project

- 2014 Video Interview with Vera Kistiakowsky, daughter of George Kistiakowsky, by Cynthia C. Kelly at Voices of the Manhattan Project

- Diary of George B. Kistiakowsky, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library

- Records of the White House Office of the Special Assistant for Science and Technology, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library

- Annotated bibliography for George Kistiakowsky from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

| Manhattan Project | |

|---|---|

| Timeline | |

| Sites | |

| Administrators |

|

| Scientists |

|

| Operations | |

| Weapons | |

| Related topics |

|

Categories:

- 1900 births

- 1982 deaths

- Scientists from Kyiv

- People from Kiev Governorate

- American physical chemists

- Manhattan Project people

- People from Los Alamos, New Mexico

- National Medal of Science laureates

- Medal for Merit recipients

- Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences

- Office of Science and Technology Policy officials

- Princeton University faculty

- Harvard University faculty

- Foreign members of the Royal Society

- Recipients of the Medal of Freedom

- White Russian emigrants to the United States

- Fellows of the American Physical Society

- Members of the American Philosophical Society

- 20th-century American chemists