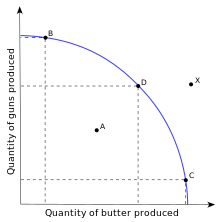

In macroeconomics, the guns versus butter model is an example of a simple production–possibility frontier. It demonstrates the relationship between a nation's investment in defense and civilian goods. The "guns or butter" model is used generally as a simplification of national spending as a part of GDP. This may be seen as an analogy for choices between defense and civilian spending in more complex economies. The government will have to decide which balance of guns versus butter best fulfills its needs, with its choice being partly influenced by the military spending and military stance of potential opponents.

Researchers in political economy have viewed the trade-off between military and consumer spending as a useful predictor of election success.

In this example, a nation has to choose between two options when spending its finite resources. It may buy either guns (invest in defense/military) or butter (invest in production of goods), or a combination of both.

Origin of the term

One theory on the origin of the concept comes from the decision to expand munitions before the US entered World War I. In 1914 the leading global exporter of nitrates for gunpowder was Chile. Chile maintained neutrality during the war and provided nearly all of the US's nitrate requirements. It was also the principal ingredient of chemical fertilizer in farming. The US realized it needed control of its own supply. The National Defense Act of 1916 directed the president to select a site for the artificial production of nitrates within the United States. It was not until September 1917, several months after the United States entered the war, that Wilson selected Muscle Shoals, Alabama, after more than a year of competition among political rivals. A deadlock in the Congress was broken when South Carolina Senator Ellison D. Smith sponsored the National Defense Act of 1916 that directed "the Secretary of Agriculture to manufacture nitrates for fertilizers in peace and munitions in war at water power sites designated by the President." This was presented by the news media as "guns and butter". Tax expert Albert Lepawsky stated in 1941, "Contrary to the popular slogan, it is not a question of guns versus butter" because basic food supplies will not be cut. He explained:

Reducing non-defense consumption as a whole, however, may play fully as important a role as increasing the nation's production. Indeed, for the first World War, it was estimated by John M. Clark that while 13 billions came out of increased production, 19 billions were paid for by decreased consumption.

Significance

"Butter" represents nonsecurity goods that increase social welfare, such as schools, hospitals, parks, and roads. "Guns" refer to security goods such as personnel—both troops and civilian support staff—as well as military equipment like weapons, ships, or tanks. Because these two types of goods represent a tradeoff, a country cannot increase one without negatively impacting the other. States often attempt to share the burden of defense through alliances. This allows a state to reduce its own production of guns and shift resources towards social goods.

If armed conflict is avoided, then expenditure on guns represents deadweight, or resources that could have been better spent on butter. In the case of war, however, the production–possibility frontier shrinks through the loss of life and infrastructure. This, in turn, limits the ability of the state to produce social goods, and the ability of society to benefit from them.

Quoted use of the term

Perhaps the best known use of the phrase (in translation) was in Nazi Germany. In a speech on January 17, 1936, Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels stated: "We can do without butter, but, despite all our love of peace, not without arms. One cannot shoot with butter, but with guns." Referencing the same concept, sometime in the summer of the same year another Nazi official, Hermann Göring, announced in a speech: "Guns will make us powerful; butter will only make us fat."

US President Lyndon B. Johnson used the phrase to catch the attention of the national media while reporting on the state of national defense and the economy.

Another use of the phrase was British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher's statement, in a 1976 speech she gave at the old Kensington Town Hall, in which she said, "The Soviets put guns over butter, but we put almost everything over guns."

Great Society example

Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society programs in the 1960s, when he was President of the United States, are examples of the guns versus butter model. While Johnson wanted to continue New Deal programs and expand welfare with his own Great Society programs, he was also involved in both the arms race of the Cold War and in the Vietnam War. These wars put strains on the economy and hampered his Great Society programs.

This is in stark contrast to President Dwight D Eisenhower's own objections to the expansion and endless warfare of the military-industrial complex. In his "Chance For Peace" speech in 1953, he referred to this very trade-off, giving specific examples:

Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed. This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children.

The cost of one modern heavy bomber is this: a modern brick school in more than 30 cities. It is two electric power plants, each serving a town of 60,000 population. It is two fine, fully equipped hospitals. It is some fifty miles of concrete pavement. We pay for a single fighter plane with a half million bushels of wheat. We pay for a single destroyer with new homes that could have housed more than 8,000 people.

This is, I repeat, the best way of life to be found on the road the world has been taking. This is not a way of life at all, in any true sense. Under the cloud of threatening war, it is humanity hanging from a cross of iron. ... Is there no other way the world may live?

See also

- Opportunity cost

- Peace dividend, the amount of civilian goods produced by a decrease in defense spending.

- Revealed preferences

- Scarcity

References

- Hibbs, Douglas (2010). "The 2010 Midterm Election for the US House of Representatives". CEFOS Working Paper. 9. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.409.410. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1691690. S2CID 154472996. SSRN 1691690.

- "Guns or Butter". Political Economy. 2011-11-24. Retrieved 2016-01-23.

- "Chile Nitrates Exports". Trade Environment Database. Washington, D.C.: American University. 1994-03-09. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-01-23.

- Price Fiushback et al. (2007) Government and the American Economy: A New History. pp. 10, 435.

- Albert Lepawsky (1941). "Paying the Bill for National Defense". Taxes 19. p. 515.

- ^ Poast, Paul (2019-05-11). "Beyond the "Sinew of War": The Political Economy of Security as a Subfield". Annual Review of Political Science. 22 (1): 223–239. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-050317-070912. ISSN 1094-2939.

- The Columbia World of Quotations. Columbia University Press. 1996. ISBN 0-231-10298-4.

- "Protest at home – Lyndon B. Johnson – war, domestic". Presidentprofiles.com. Retrieved 2016-01-23.

- Speech at Kensington Town Hall ("Britain Awake"), Margaret Thatcher Foundation

Further reading

- Carlton-Ford, Steve. 2009. Major Armed Conflicts, Militarization, and Life Chances: Pooled Time-Series Analysis. Armed Forces & Society, Vol. 36, No. 5.

- Uk Heo and Sung Deuk Hahm. 2006. Politics, Economics, and Defense Spending in South Korea. Armed Forces & Society, Vol. 32, No. 4.

- Ward, Michael D., David R. Davis and Steve Chan. 1993. Military Spending and Economic Growth in Taiwan. Armed Forces & Society, Vol. 19, No. 4.