The history of the oil shale industry in the United States goes back to the 1850s; it dates back farther as a major enterprise than the petroleum industry. But although the United States contains the world's largest known resource of oil shale, the US has not been a significant producer of shale oil since 1861. There were three major past attempts to establish an American oil shale industry: the 1850s; in the years during and after World War I; and in the 1970s and early 1980s. Each time, the oil shale industry failed because of competition from cheaper petroleum.

As of 2014, there are a number of companies doing research and development on oil shale deposits in Colorado and Utah, but there is no commercial production of oil from shale in the United States.

US oil shale resources

Main article: Oil shale reservesThe United States has not had a viable oil shale industry for more than 150 years, yet it contains the largest oil shale resource in the world.

Eastern resources

There are two types of oil shale resources in the United States east of the Mississippi River. The first is cannel coal, which was used widely in Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and western Virginia (now West Virginia) to manufacture oil during the first American oil shale boom, 1854–1861. The cannel coals have since been largely mined out, and are no longer considered a major oil-shale resource.

The second category of eastern oil-shale resources are the Paleozoic black shales, of lower oil yield, but of much larger size than the cannel coals. Most attention has been given to the shales near the Devonian/Mississippian boundary, which are variously called the Ohio Shale, Chattanooga Shale, the Antrim Shale, and the New Albany Shale.

Western resources

Black shales similar to the eastern shales are widely distributed west of the Mississippi River. These include some, such as the Woodford Shale of Oklahoma, which are near-stratigraphic equivalents to the Devonian/Mississippian shales of the eastern US.

The largest oil-shale resource in the world is contained in the Eocene Green River Formation in Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming in three basins: the Piceance Basin, Green River Basin, and Uinta Basin. The Green River oil shales have been the focus of most efforts of the past hundred years to establish an American oil shale industry.

The Green River oil “shale” is actually a marl, and some beds yield up to 70 gallons of oil per short ton of shale. Estimated in-place resources are capable of generating 4.2 trillion barrels of oil. Although the Piceance basin of western Colorado has the smallest lateral extent of Green River shale, it contains the greatest amount of high-grade shale. Using a cut-off of 25 gallons per ton, the Piceance has about 352 billion barrels of in-place resource.

The Elko Formation of northeastern Nevada is an oil shale, late Eocene to early Oligocene in age. Like the Green River Formation, it contains beds deposited in a lake. Faulting and subsequent erosion have removed most of the original extent of the deposit, leaving isolated bodies of the formation within an area about 100 miles long and 30 miles wide in Elko County, Nevada.

The Phosphoria Formation of Permian age is present in Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana. Some beds were found to yield more than 25 gallons of oil per ton.

1850s – the coal oil era

America faced a shortage of oil – whale oil. Despite a steadily growing fleet of whaling ships, the American whaling industry could not satisfy the demand for lamp oil; the price had risen considerably, and the country imported increasing amounts of whale oil.

Whale oil was needed as lamp oil for illumination. It burned with a bright, smokeless flame that nothing else was known to match. Chemists had known how to make oil from coal (coal oil) or turpentine (camphene) for many years, but they burned with sooty flames, making them unsuitable for indoor illumination. The only viable competitor to whale oil was “burning oil,” a mixture of camphene and alcohol, which burned bright and smokeless, but which was volatile and prone to explode. Fire insurance policies charged higher premiums for buildings in which camphene-based lamp oil was used. The city of Lowell, Massachusetts banned the storage of products containing camphene within 200 yards of any building in the city.

The increasing demand for whale oil decimated the whale populations in the mid-1800s. The number of whales caught rose each year, until the American whaling industry produced another record amount of whale oil in 1846, after which the whale hunting deteriorated . The increasing number of whaling ships partly compensated for the lower catch per ship each year, but the fleet could never again match the record catch of 1846. The shortage of whale oil caused both the price and the level of imports, to jump.

As the price of whale oil escalated, scientists tried to create a cheap, artificial oil that would burn with a bright, smokeless flame, safer than “burning oil.” Two succeeded: Scottish chemist James Young, and Canadian geologist Abraham Gesner. Both distilled their lamp oils from coal or coal-like raw materials. James Young made his from coal, and discovered that the coal that yielded the most oil was cannel coal. Young filed a patent for his process in 1850, and built a highly successful plant at Bathgate, Scotland making an illuminating oil he called “paraffine,” from the cannel coal that was mined nearby, the Boghead coal, which yielded more oil than any of the other coals he tested.

By 1853, Canadian geologist Abraham Gesner had learned to distill a good-quality lamp oil from a rock called “albertite,” found in New Brunswick, Canada. It was a matter if dispute whether albertite was coal or hardened petroleum. Gesner moved from Halifax, Nova Scotia to New York City in early 1853, and in March 1853 he circulated a prospectus for the Asphalt Mining and Kerosene Gas Company. The company bought a plot of land in Brooklyn, primarily to manufacture coal gas from albertite imported from New Brunswick, but the prospectus also mentioned that the Gesner's process would also yield 15 gallons per ton of “Kerosine, or Burning Fluid.” The company reorganized in 1854 as the North American Kerosene and Gas Light Company. That same year, Gesner received a patent for his process to make a lamp oil he named Kerosene. Kerosene soon became the principal money-maker for Gesner's company.

The coal oil "mania"

The successes of Young and Gesner attracted a flood of imitators. The Scientific American noted that the number of American companies making coal oil grew from three at the end of 1857, to 42 or more at the end of 1859. The magazine said that the rush to establish coal-oil works resembled “a mania,” and attributed it to the “impetuous energy” of the American people.

In the mid-1850s, whale-oil dealer Samuel Downer Jr. bought the near-bankrupt United States Chemical manufacturing company of Waltham, Massachusetts. The firm manufactured lubricating oil from coal, but the oil sold poorly because of its strong odor. With Downer's financial backing, the firm perfected its lubricant. After a company chemist returned from a visit to the Scottish oil shale region, the firm switched emphasis to lamp oil, which it manufactured at Waltham, as well as at another factory it built at Portland, Maine. Both works used albertite imported from New Brunswick. By the end of 1858, the Downer Company had 50 retorts, and dominated the coal oil business in the northeast.

The first American shale oil/coal oil manufacturer using non-imported coal was the Breckinridge Cannel Coal Company, chartered by the Kentucky legislature in 1854. In 1856 its twelve new retorts at Cloverport, Kentucky began producing 600 to 700 US gallons per day (2.3 to 2.6 m/d) of lamp oil each day. The company had the advantages of proximity to large deposits of cannel coal from the Breckinridge coal deposit in Hancock County, Kentucky, and a location on the Ohio River, providing cheap shipping to markets. Commercial-scale shale oil extraction, other than cannel coal processing, began at shale oil retorts using the Devonian oil shale along the Ohio River Valley in 1857.

Shale oil manufacturers followed two geographic patterns: place the retorts close the customers, or close to the oil shale.

The first pattern was to place the retorts in or near a major market along the East Coast, and use shale or coal shipped long distances, usually imported from New Brunswick or Scotland. Shale oil manufacturers established themselves along the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic coast from Portland, Maine, to Baltimore. New York had at least fourteen shale oil companies, and Boston seven.

The second pattern was to locate the retorts close to the oil shale, and ship only the product long distances. The oil shale industry of the Ohio River Valley followed this model. At least 25 shale oil manufacturers set up retorts along the Ohio River and its navigable tributaries from Pittsburg on the east to St. Louis (on the Mississippi River) on the west. Major coal-oil centers were Pittsburg, with four coal-oil companies; Cincinnati, with three; and Kanawha, Virginia (now West Virginia), with six companies. Kentucky had six coal-oil manufacturers.

By early 1860, there were between 60 and 75 shale oil companies in the United States, producing from seven to nine million gallons annually of lamp and lubricating oil. Lamp oil from shale was reportedly much improved, and free from its early problems of smoke and odor. It was hailed as giving “more and cheaper light than any other substance,” and was driving the turpentine-based (camphene) lamp oils, as well as the much more expensive whale oil, from the market.

The coal oil industry is ruined by cheap petroleum

Today, oil shale is an “unconventional” energy source, and drilling for crude oil is the norm. But in the late 1850s, those positions were reversed. By 1859, when some venture capitalists hired Edwin Drake to drill for oil in western Pennsylvania, the oil shale industry was well established, and it was the idea of drilling for crude oil that was unproven.

Petroleum distillation had been going on in the US at a small scale since 1851, when Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania salt manufacturer Samuel Kier began taking the petroleum which was fouling his salt wells, and distilling it in a five-gallon still into lamp oil which he sold to coal miners. Kier never patented his distillation process, and production was limited by the small supply of petroleum that seeped into his salt wells.

On 28 August 1859, Edwin Drake discovered oil in a well 70 feet deep along Oil Creek, south of Titusville, Pennsylvania. The well made only 12 to 20 barrels per day, but the discovery set off a boom in oil drilling up and down Oil Creek, and then all down the Ohio valley, to Ohio, Kentucky, and Virginia, the same area where many shale oil retorts were located. In 1861, petroleum flooding onto the market drove the price down to US$0.52 per barrel, and lamp oil refiners switched over to petroleum as a much cheaper raw material. Refining petroleum had the further advantage that the process was not patented, allowing refiners to produce lamp oil without paying royalties. The existing shale oil refineries were forced by price-cutting competition to adapt their operations to use petroleum instead, and the American oil shale industry, booming just the previous year was suddenly abandoned. Cheap petroleum prices had driven oil shale out of business.

World War I and gasoline boom

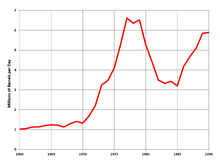

World War I put a strain on US and world oil supplies, but even after the war, petroleum consumption kept its rapid rise, as Americans bought record numbers of automobiles. Despite steadily growing domestic petroleum production, the American oil industry could not supply the rapidly growing demand, especially for gasoline, and the country had to import increasing amounts of oil, raising prices, and causing widespread speculation that petroleum would be soon exhausted.

America was quickly running out of petroleum and into a permanent state of energy scarcity – or at least many experts said so.

- "... the peak of production will soon be passed, possibly within 3 years. ... There are many well-informed geologists and engineers who believe that the peak in the production of natural petroleum in this country will be reached by 1921 and who present impressive evidence that it may come even before 1920."

- - David White, chief geologist, United States Geological Survey (1919)

- “The average middle-aged man of today will live to see the virtual exhaustion of the world’s supply of oil from wells,”

- - Victor C. Anderson, president of the Colorado School of Mines (1921)

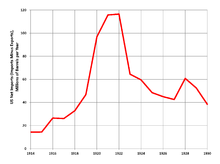

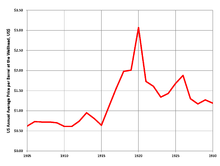

The average price of crude oil in the United States more than tripled, going from $0.64 per barrel in 1915 to US$2.01 in 1920. Domestic oil production grew, but lagged farther behind consumption, and net imports of crude oil to the US rose sharply, from 18 million barrels in 1915 to 106 million barrels in 1920.

The nation's largest oil shale resource, Green River Formation, was accidentally discovered in 1874. That beds of the Green River Formation could yield oil upon heating had been known for years, but the publication in 1914 of US Geological Survey Bulletin 581, "Oil-Shale in Northwestern Colorado and Northeastern Utah" brought the enormous size of the resource to public attention.

Concerned that a coming oil famine could strand the American fleet, in 1912 President Taft created the first three Naval Oil Reserves, large federal tracts thought to have oil deposits (two in California and one in Wyoming), which would not be tapped unless the Navy could no longer buy oil from other sources. In view of the expected importance of oil shale in the near future, President Woodrow Wilson in 1916 established two Naval Oil Shale Reserves, large tracts of prime oil shale that were kept from passing into private ownership. Oil Shale Reserve 1 (26,406 acres) was in Garfield County, Colorado, eight miles west of the town of Rifle. Oil Shale Reserve 2 (88,890 acres) was in Carbon and Uintah counties, Utah. Oil Shale Reserve 3 (20,171 acres), in Colorado, was added later.

The first western oil shale boom

- "the potential industry has suffered much harm by the fake promoter and his fake companies."

Attracted by rising oil prices, and the promise of a permanent shortage of petroleum, oil-shale prospectors swarmed over the Piceance and Uinta basins of Colorado and Utah. Some established oil companies joined the rush, but about 100 new companies formed to mine and process oil shale, and, not incidentally, to sell shares of stock. Many of them built retorts to extract the shale oil.

Many of the new companies were legitimate, but the honest ones had to compete with the exaggerated promises of the crooks. Oil shale processing worldwide had always included a retort to produce oil by heating the shale, and a separate refining process to make marketable products from the oil. But some promoters claimed to be able to draw gasoline and other consumer products directly from the retort. One huckster promised that he could extract gold from the oil shale as a byproduct. The US Bureau of Mines had to go out of its way to assure the public that it could not detect recoverable amounts of gold in any oil shale.

At the start of the boom in 1915, oil and oil shale were still locateable minerals under the General Mining Act of 1872. Any US citizen could stake a placer claim to reserve the mineral rights over 160 acres of oil-shale land. Congress changed the situation when it passed the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920, which declared that oil and oil shale were no longer locateable minerals, but instead the rights to mine them had to be leased from the federal government.

In September 1920, of the many oil shale companies being promoted, none were yet in commercial-scale operation, although five were said to be close. Of the five, one plant was near Dragon, Utah, one at Salt Lake, two at Elko, Nevada, one at Denver, and one at Dillon, Montana. The plant at Dillon was mining oil shale of the Phosphoria Formation, Permian in age. The American Continuous Retort plant in Denver was receiving test lots from western Colorado, and as far away as Texas and Kentucky, largely on the proprietor's claim that he could recover gold and platinum from the shale, along with the oil.

First attempt to produce oil from the western deposits was made by mining engineer Robert Catlin. Catlin became intrigued by oil shale, and in 1890 bought a plot of land near Elko Nevada that was underlain by oil shale of the Elko Formation. When the price of oil started rising in 1915, he dug a mine shaft down into the best yielding shale, built a bank of retorts and a small refinery, and began producing oil. He refined the oil into gasoline and lubricating oil, but the products were said to be of low quality. in 1917 he incorporated Catlin Shale Products Company. Catlin's plant at Elko produced about 12,000 barrels (1,900 m) of oil from shale before he closed it in 1924. Catlin Shale Products Company was dissolved in 1930. Of the hundred-odd companies that formed to produce shale oil in the postwar boom, only Carlin's had actually done so on a commercial scale and marketed the product.

The first attempts to exploit the Green River Formation deposit was made by establishment of The Oil Shale Mining Company in 1916. In 1917, they erected the first commercial retort at the head of Dry Creek, near De Beque, Colorado. However, also these attempts were unsuccessful and by 1926 the company had lost its property. In addition, companies like Cities Service, Standard Oil of California, Texaco and Union started their oil shale operations in 1918–1920. In 1915–1920 about 200 companies were established to exploit oil shale and at least 25 shale oil retorting processes reached to the pilot-plant stage.

Although most of the attention had shifted to the oil shale of the Green River Formation in Colorado and Utah, a number of companies also tried to develop the eastern Devonian shales, mostly the New Albany Shale in Kentucky and Indiana. Although the eastern shales had a lower oil yield than the western shales, they had the advantages of better infrastructure, abundant water supply, and proximity to markets. At the beginning of 1923, a retort was reported to be making test runs on local Sunbury Shale in Pike County, Ohio, and another southern Ohio oil shale retort was being planned.

Shale oil industry and cheap petroleum

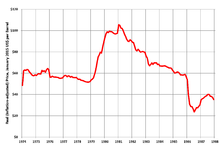

The high price of petroleum encouraged intensified exploration in the US and elsewhere, and eventually resulted in the discovery of large new petroleum deposits. American oil production surged in the early 1920s, particularly in north Texas and the Los Angeles Basin in California, driving down both imports and the price of oil. A barrel of oil in the Midcontinent region lost almost two-thirds of its value, falling from US$3.50 at the start of 1921, to US$1.25 at year-end. Imported oil peaked at 127 million barrels in 1923, then dropped by more than half, to 62 million in 1925.

The drop in oil price, and the increased production from new fields, put a damper on speculation that the US was about to run out of oil. Oil shale could not economically compete with petroleum priced below US$2 per barrel, especially given that the productive shale areas were far from major petroleum markets. Cheap petroleum prices had driven oil shale out of business.

Between the booms

Some companies continued to work on better ways to process oil shale. One of technological achievements before World War II was invention of the N-T-U retort. In 1925, the NTU Company built a test plant at Sherman Cut near Casmalia, California. In 1925–1929, the retort was also tested by the United States Bureau of Mines in their Oil Shale Experiment Station at Anvil Point in Rifle, Colorado.

Concern about long-term oil supplies during World War II had prompted Congress in 1944 to pass the Synthetic Liquid Fuels Program with goal to establish a liquid fuel supply from domestic oil shale. It funded oil-shale studies by the US Bureau of Mines. The Bureau of Mines built a test facility at Anvil Points on Naval Oil Shale Reserve 1, to test methods of mining, crushing, and retorting the Green River oil shales. It started to develop the gas combustion retort process. In 1943 Mobil Oil built a pilot shale oil extraction plant and in 1944 Union built an experimental oil shale retort. In 1945 Texaco started shale oil refining study.

In 1951, the United States Department of Defense became interested in oil shale as an alternative resource for producing a jet fuel. The United States Bureau of Mines continued its research program at Anvil Point until 1956. It opened a demonstration mine which operated at a small scale. From 1949 to 1955 it also tested the gas combustion retort. The program ended in 1956. In 1964 the Avril Point demonstration facility was leased by Colorado School of Mines and was used by Mobil-led consortium (Mobil, Humble, Continental, Amoco, Phillips and Sinclair) for further development of that type of retort. In 1953, Sinclair Oil Corporation developed an in-situ processing method using existing and induced fractures between vertical wells. In the 1960s, a proposal known as Project Bronco, was suggested for a modified in situ process which involved creation of a rubble chimney (a zone in the rock formation created by breaking the rock into fragments) using a nuclear explosive. This plan was abandoned by the Atomic Energy Commission in 1968. Companies developing experimental in-situ retorting processes also included Equity Oil, ARCO, Shell Oil and the Laramie Energy Technology Center.

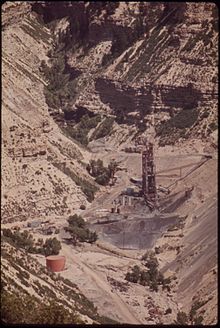

By the 1940s, companies such as Chevron and Texaco owned substantial oil shale areas. A number of oil companies started researching methods to mining and process the oil shale. In contrast to the boom of the 1920s, which featured hundreds of small startup companies operating on stock sales, the shale research after World War II was a well-financed, long-term effort by established oil companies. Sinclair Oil began testing an in-situ combustion process for recovering shale oil in the 1950s. Union Oil Company of California built and tested its proprietary Union process with a 1,200 ton-per-day retort at its Parachute Creek property near Grand Valley, Colorado in 1957 and 1958. This technology was tested between 1954 and 1958 at the company-owned tract in the Parachute Creek. This production was finally shut down in 1961 due to cost. In 1957 Texaco built a shale oil extraction pilot plant to develop its own hydroretorting process. In the early 1960s TOSCO (The Oil Shale Corporation) opened an underground mine and built an experimental plant near Parachute, Colorado. It was closed in 1972 because the price of production exceeded the cost of imported crude oil. The federal government offered for lease three large blocks of oil shale land in Colorado in 1968, but rejected all the received bids as insufficient.

1970s - the energy crisis

America faced a shortage of oil. A confluence of factors combined to create what was called the energy crisis of the 1970s. American crude oil production declined after peaking in 1970, and the country had to import increasing amounts of petroleum. US natural gas production declined after peaking in 1971. A booming world economy turned the buyer's market for oil in the late 1960s into a seller's market in the early 1970s. OPEC took advantage of the tight market to pressure oil companies to pay higher prices. In 1973, some Arab countries stopped shipping oil to nations supporting Israel, including the United States. The abrupt changes in oil price and supply occurred at a time when federal price controls made it difficult for the American economy to adapt to new market conditions. Allocations of scarce gasoline was controlled by the federal "Energy czar." Gasoline stations ran out of product, and drivers waited in block-long lines to fill their tanks.

America was quickly running out of oil and into a permanent state of energy scarcity, or at least many experts said so. Geologist King Hubbert had successfully predicted the approximate year of the peak in US production, and his model predicted a continued and steepening decline in US oil production. The highly influential 1972 Club of Rome report Limits to Growth predicted that the world was entering an era of increasingly scarce mineral resources.

The federal government responded with numerous initiatives, one of which was to encourage domestic oil shale production by leasing large tracts of oil shale land in Colorado and Utah.

The new oil shale boom

The United States Navy and the Office of Naval Petroleum and Oil Shale Reserves started evaluations of oil shale's suitability for military fuels, such as jet fuels, marine fuels and a heavy fuel oil. Shale-oil based JP-4 jet fuel was produced until the early 1990s, when it was replaced with kerosene-based JP-8. Seventeen companies led by Standard Oil of Ohio formed the Paraho Development Corporation to develop the Paraho process. Production started in 1974 but was closed in 1978. In 1974 the United States Department of the Interior announced an oil shale leasing program in the oil shale regions of Colorado and Utah. In 1980 the Synthetic Fuels Corporation was established which operated until 1985.

In 1972, the first modified in situ oil shale experiment in the United States was conducted by Occidental Petroleum at Logan Wash, Colorado. Rio Blanco Oil Shale Company, a partnership between Gulf Oil and Standard Oil of Indiana, originally considered using Lurgi–Ruhrgas above-ground retort but in 1977 switch also to the modified in-situ process. In 1985 the company ceased its operations. The White River Shale Corporation, a partnership of Sun Oil, Phillips and Sohio, existed between 1974 and 1986 for developing the tract in the Uintah Basin on the White River area.

In 1977, Superior Oil Company cancelled its Meeker shale oil plant project. Year later Ashland, Cleveland Cliffs Company and Sohio exited the Colony Shale Oil Project near Parachute, Colorado. Also, Shell exited the Colony project but continued with in-situ test.

In 1970, the Bureau of Mines estimated that shale oil would cost US$2.71 per barrel before profit and taxes.

TOSCO (standing for The Oil Shale Corporation) developed its own retorting process, and in 1963 formed the Colony Development Co. to build and test a 1,000-ton per day processing plant on Parachute Creek, on a 22-square mile tract of oil shale. Colony Development was a consortium of TOSCO, Cleveland-Cliffs Iron Co., and Standard Oil of Ohio (SOHIO). The Colony plant began construction in 1965.

Engineering Development, Inc. leased the Naval Oil Shale Reserve 1 at Anvil Points in 1972, and formed the Paraho Development Corporation in 1973 as a consortium of 17 energy companies, among them Chevron and Texaco. The company based its plans on its proprietary Paraho process retorting technology, which achieved oil recoveries of greater than 90 percent. Besides the Anvil Points lease, Paraho leased some oil shale acreage in Utah, but did no work on the Utah properties. The company produced more than 100,000 barrels of shale oil at Anvil Points in the late 1970s.

Sunoco and Phillips Petroleum jointly submitted the US$76 million winning bid on the 5,120-acre Federal Tract U-a in Utah, and formed the White River Shale Oil Corporation to run the project. SOHIO bought into the White River Corporation, and in 1975 the partners won the lease on the adjacent 5,120-acre U-b tract with a US$45 million bid. The company planned to produce 100,000 barrels of shale oil per day by underground mining and surface retorts, but both leases were suspended from 1976 and 1980 because of environmental and land title issue, stopping all development.

Gulf Oil and Chevron Corporation formed the Rio Blanco Oil Shale Company in 1974 as a 50:50 partnership to enter the oil shale business. That same year Rio Blanco won a lease on the first BLM tract put up for competitive bidding, with a winning bid of US$210.3 million. Tract C-a covered 5,100 acres, about eight square miles. Rio Blanco had planned to mine oil shale from an open pit, but wanted the BLM to make additional land available for off-site disposal of the overburden, which the BLM declined. The company turned to in situ mining. Underground combustion was started in 1980. Two more burns were started in 1981, and the company recovered about 25,000 barrels of oil until a water pump failed, and groundwater prematurely extinguished all three underground burns in 1984.

in 1976, a consortium of TOSCO, Shell Oil, Atlantic Richfield Company, and Ashland Oil, leased from the federal government 5,000-acre Tract C-b, located between Rifle, Meeker, and Rangely. The company put down a mine shaft 2,000 feet, from which they planned to drive a network of tunnels horizontally, and mine by conventional room-and-pillar. ARCO and TOSCO withdrew from the Tract C-b joint venture, leaving Shell and Ashland. In 1977, Shell sold its part to Occidental, and Ashland later sold out what was then known as the Cathedral Bluffs project to Tenneco. Occidental Petroleum Corporation had been began producing shale oil with in situ methods at its test tract near Debeque, Colorado. Pleased with the test-scale results, Oxy scrapped plans for conventional mining at Cathedral Bluffs in favor of its in situ process, in which they would drive a network of tunnels out from the mine shaft, break the oil shale with explosives, and produce oil underground by controlled combustion. The shale oil would then be pumped to the surface. The calculated recovery was 1.2 billion barrels over the project life.

Chevron and Conoco joined in 1981 to start the Clear Creek Project, north of Debeque. The plan was to produce shale oil by underground mining and surface retorting. The partners pilot-tested retort designs at the Chevron refinery outside Salt Lake City.

Already-large oil companies entering the oil shale business found their potential reserves increased enormously. Union Oil's shale property promised to increase that company's oil production by 50% overnight, and maintain production at that level for 40 years. But as the projects developed, the companies found themselves with multibillion-dollar bets on the economic viability of oil shale, and some looked for partners to spread the risk; some sold out entirely.

The Colony Oil Shale Project changed hands a number of times, until the only original owner left was TOSCO with 40%. The rest was owned by Exxon. The partners planned a US$5 billion project to mine and process oil shale.

Black Sunday and the demise of the American shale oil industry 1982-1991

Once again, oil shale fell victim to lower petroleum prices. The oil price began to slump in 1981, and starting in late 1981, one by one, the oil shale players folded on their billion-dollar bets, took their losses, and halted efforts at commercial production.

In December 1981, Occidental Petroleum and Tenneco announced that they were suspending work on the Cathedral Bluffs project, and laying off hundreds of employees. The company cited rising construction costs and slumping oil prices as the reasons. With financial aid from the government Synthetic Fuels Corporation in 1983, the Cathedral Bluffs company revised its plan, and applied for a contract with Synthetic Fuels Corporation to sell it 14,100 barrels of shale oil per day, produced by room-and-pillar mining and surface retorting. But negotiations dragged on, and the Synthetic Fuels Corporation was defunded by the Reagan administration in 1985. Pumping and maintenance of the shaft were suspended in 1991, and the shaft house was demolished in 2002. The project had not produced any oil.

The date usually cited as the end of the oil shale boom is Sunday, 2 May 1982, known locally as “Black Sunday,” when Exxon announced that it was closing its Colony Oil Shale Project and laying off more than 2,200 workers. The project, with a final price tag of US$5 billion, had cost its owners more than $1 billion by the time they quit. No commercial shale oil had been produced.

All the towns in the vicinity suffered economically. The community of Battlement Mesa, built to house the now laid-off employees of the Colony oil shale project, became an instant ghost town. But the community was rescued from disappearance when its properties were marketed as retirement homes on Colorado's sunny western slope, and at a bargain price. Enough retirees took advantage of the oil shale bust to turn the town around in just a few years.

Of the attempts to open commercial-scale oil shale operations, only the Union Oil project continued. Union Oil persevered to the extent of spending $1.2 billion, and shipped its first barrel of oil in 1986. The plant was making 5,000 to 7,000 barrels per day at peak production, helped by a federal subsidy. In 1986, President Ronald Reagan signed into law the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 which among other things abolished the United States' Synthetic Liquid Fuels Program. Union finally bowed to continued low oil prices and closed the project in 1991, rather than complete the US$2 billion project.

Over several decades, some of the world's largest oil companies (Amoco, Arco, Chevron, Exxon, Gulf, Phillips, Shell, Sohio, Sunoco, Texaco, Union Oil) had spent billions of dollars to start an oil shale industry in the Green River Formation, the world's largest oil shale resource. But in the end, cheap petroleum prices drove oil shale out of business.

Oil shale in the 21st century

| This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (February 2015) |

Even after the oil shale bust, some companies persevered. Shell Oil continued testing in situ methods, and in 1997 started a field test of the Shell in situ conversion process. In 2016 Shell successfully tested its in situ process in Jordan, and later spun the technology out to create Salamander Solutions.

An oil shale development program was initiated in 2003. The Energy Policy Act of 2005 directed the Department of Energy and the Department of the Interior to begin a program of leasing federal land for commercial oil shale production. The BLM had already proposed a phased approach, which would allow companies to do research and development, followed by a demonstration project on a lease tract of 160 acres, before expanding into commercial-scale production on a tract up to 4,960 acres adjacent to the initial 160 acres, for a total leased area of 5,120 acres or 8 square miles.

In 2005 the government solicited nominations to lease federal land for oil shale research, development, and demonstration (RD&D) projects, and in 2006 and 2007 issued six leases: five in Colorado and one in Utah. All the leases in Colorado were to test in situ processes; the Utah lease was to test underground shale mining with surface retorts. Shell Oil won three of the leases, to test three different methods, all in Rio Blanco County, Colorado; two of the projects would also recover the sodium mineral nahcolite. Chevron and EGL Resources each won a lease in Rio Blanco County. The Vernal County, Utah lease was won by Enefit American Oil. In 2008, the BLM finished a programmatic environmental impact statement (PEIS) for the RD&D projects.

In 2010, the BLM selected for further consideration three applications for RD&D leases: two in Rio Blanco County, Colorado, and one in Vernal and Uintah counties, Utah. The Colorado lease bids were from ExxonMobil and Aura Source; the Utah bid was from Natural Soda Holdings. No leases were awarded, and they are pending results of a new programmatic environmental impact statement ordered by the Obama administration.

In 2011, the Obama administration halted further nominations for oil shale leasing until the PEIS is finished, and to allow a government review to assure that the lease terms are not economically skewed in favor of the oil companies. As of January 2015, the new PEIS has not been issued.

Chevron closed its Chevron CRUSH project in 2012 and Shell closed its Mahogany Research Project in 2013.

References

- K.F. Rheams and T.L. Neathery, “Characterization and geochemistry of Devonian oil shale, north Alabama – south central Tennessee,” Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine Symposium on Characterization and Chemistry of Oil Shales, American Chemical Society, April 1984.

- Ron Johnson, Oil-shale overview, US Geological Survey, accessed 11 Jan. 2015.

- ^ Nevada Bureau of Mining and Geology, Oil shale, accessed 16 Jan. 2015.

- D. Dale Condit, Oil Shale in Western Montana, southeastern Idaho, and adjacent parts of Wyoming and Utah, US Geological Survey, Bulletin 711-B.

- George William Clinton, A Digest of the Reported Decisions in Law and in Equity, of the Courts of New York, v.2 (Albany, N.Y.: Van Benthuysen, 1860) 1735.

- The Charter and Ordinances of Lowell, Massachusetts, 1863.

- ^ Lucier, Paul (2008). Scientists & Swindlers. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 149–156. ISBN 978-0-8018-9003-1.

- ^ ”Coal oil manufacture,” Scientific American, 2 Jan. 1860, v.2 n.1 p.3.

- Runnels, Russell T.; Kulstad, Robert O.; McDuffee, Clinton; Schleicher, John A. (1952). "Oil Shale in Kansas". Kansas Geological Survey Bulletin (96, part 3). University of Kansas Publications. Retrieved 2009-05-30.

- Thomas Antisell, The Manufacture of Photogenic or Hydro-Carbon Oils (New York: Appleton, 1860) 16.

- ”Baltimore, Maryland,” Hunt’s Merchants’ Magazine, May 1860, v.42 n.5 p.573.

- James C. Hower, “The cannel coal industry of Kentucky,” Energeia, University of Kentucky Center for Applied Energy Research, 1996, v.7 n.1.

- "Oil shale: History of oil shale use". Kansas Geological Survey Bulletin. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2014-09-06.

- ^ OTA (1980), p. 110

- David White, "The unmined supply of petroleum in the United States," Transactions of the Society of Automotive Engineers, 1919, v.14, part 1, p.227.

- “The present status of the oil shale industry" 1921, Colorado School of Mines Quarterly, Apr. 1921, v.16 n.2 p.12.

- ^ US Bureau of the Census, 1960, Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1957, p.361.

- Gallois, Ramues (1978-02-23). "What price oil shales?". New Scientist. 77 (1091): 490–493. ISSN 0262-4079.

- ^ Martin J. Gavin, 1922, Oil-Shale: An Historical and Economic Study, US Bureau of Mines, Bulletin 210, p.100.

- Andrews (2006), p. 2

- Dean E. Winchester, “Oil for the United States Navy,” Colorado School of Mines Quarterly, Oct. 1924, v.19 n.4 p.85.

- H.L. Wood, "Record of oi shale development in the United States," National Petroleum News, 29 Sept. 1920, p.33-38.

- ^ EPA (1979), pp. C-1–C-2

- Doug Harper, "Fifty years too soon," Northeastern Nevada Historical Society Quarterly, Fall 1974, v.5 n.2 p.18.

-

Mehls, Steven F. (1982). The Valley of Opportunity: A History of West-Central Colorado. Colorado Cultural Resources Series. ISBN 9781496015587.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Victor C. Anderson, “Oil shale: a resume for 1922,” Colorado School of Mines Quarterly, Jan. 1923, v.18 n.1 p.8.

- Harold F. Williamson and others, The American Petroleum Industry: The Age of Energy 1899-1959 (Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern Univ. Press, 1963) 299-303.

- Ralph H. McKee, “Shale oil, a general view of the industry,” in Ralph H. McKee and others, Shale Oil (New York: Chemical Catalog Co., 1925) 17.

- ^ OTA (1980), p. 139

- "California, Oil Shale, Progress in 1925". Journal of the Institution of Petroleum Technologists. 12. Institution of Petroleum Technologists: 371. 1926.

- Carter et al. (1939), p. 373

- ^ Andrews (2006), p. 9

- "History". Environmentally Conscious Consumers for Oil Shale. Archived from the original on 2013-09-07. Retrieved 2011-05-06.

- OTA (1980), p. 140

- Lee (1990), p. 124

- Lombard, D.B.; Carpenter, H.C. (1967). "Recovering Oil by Retorting a Nuclear Chimney in Oil Shale". Journal of Petroleum Technology. 19 (6). Society of Petroleum Engineers: 727–734. doi:10.2118/1669-PA. ISSN 0149-2136. SPE-1669-PA.

- ^ Bunger et al. (2004), pp. A2–A3

- ^ Schramm, L.W. (1970). "Shale oil," in Mineral Facts and Problems. US Bureau of Mines, Bulletin 650. pp. 183–202.

- Richard D. Dayvault, A chronology of Union Oil's oil shale activities.

- Merrow (1978), p. 107

- BLM (2008), p. A-15

- Dhondt, R.O.; Duir, J.H. (13–16 October 1980). Union Oil's Shale Oil Demonstration Plant (PDF). Synthetic Fuels–Status and Directions. Electric Power research Institute. pp. 16-1–16-23. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- Laherrère, Jean (2005). "Review on oil shale data" (PDF). Hubbert Peak. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-06-17.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Chandler, Graham (2006). "US eyes Alberta as model for developing oil shale". Alberta Oil. 2 (4): 16–18. Archived from the original on 2014-09-07. Retrieved 2014-09-07.

- Daniel Yergin, The Prize (New York: Free Press, 2009) 572.

- US Department of Energy, Timeline 1971-1980 Archived 2014-05-03 at the Wayback Machine

- OTA (1980), p. 124

- Knutson, Carroll F. (1986). "Developments in Oil Shale in 1985". AAPG Bulletin. 70. American Association of Petroleum Geologists. doi:10.1306/94886C86-1704-11D7-8645000102C1865D.

- Aho, Gary (2007). OSEC's Utah oil shale project (PDF). 27th Oil Shale Symposium. Golden, Colorado: Colorado School of Mines. Retrieved 2014-09-07.

- EPA (1979), pp. C-3

- ^ Proposed Oil Shale and Tar Sands Resource Management Plan Amendments. US Bureau of Mines, FES 08-32. September 2008. pp. A-14–A-21.

- Occidental Petroleum Corporation, 1979, “This is tract C-b,” 4-page brochure, 1979.

- Union Oil Company of California, Sign of the 76 (Los Angeles: Union Oil, 1976) 390.

- Gary Schmitz, “Oil sale project suspended,” Palm Beach Post, 18 Dec. 1981.

- "Oil shale—enormous potential but...?" (PDF). RockTalk. 7 (2). Division of Minerals and Geology of Colorado Geological Survey. April 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-01. Retrieved 2007-07-28.

- Collier, Robert (4 September 2006). "Coaxing oil from huge U.S. shale deposits". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

- Bartis, James T.; LaTourrette, Tom; Dixon, Lloyd; Peterson, D.J.; Cecchine, Gary (2005). Oil Shale Development in the United States. Prospects and Policy Issues. Prepared for the National Energy Technology Laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy (PDF). RAND Corporation. ISBN 978-0-8330-3848-7. Retrieved 2009-01-17.

- "Colorado oil shale boom turns into a bust," Lewiston Sun 2 May 1982.

- Andrews (2006), p. 11

- "Nominations for Oil Shale Research Leases Demonstrate Significant Interest in Advancing Energy Technology. Press release". BLM. 2005-09-20. Archived from the original on 2008-09-16. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- Peter M. Crawford and others, Assessment of Plans and Progress on US Bureau of Land Management Oil Shale RD&D leases in the United States, 29 April 2012.ISBN=

- "Chevron leaving Western Slope oil shale project". Denver Business Journal. 2012-02-28. Retrieved 2012-03-12.

- Hooper, Troy (2012-02-29). "Chevron giving up oil shale research in western Colorado to pursue other projects". The Colorado Independent. Retrieved 2014-03-31.

- Jaffe, Mark (2013-09-25). "Shell abandons Western Slope oil-shale project". The Denver Post. Retrieved 2014-09-07.

Bibliography

- Andrews, Anthony (2006-04-13). Oil Shale: History, Incentives, and Policy (PDF). Congressional Research Service. RL33359.

- "Appendix A: Oil Shale Development Background and Technology Overview". Proposed Oil Shale and Tar Sands Resource Management Plan Amendments to Address Land Use Allocations in Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming and Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement (PDF). BLM. September 2008. FES 08-32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-02-16. Retrieved 2015-01-24.

- Bunger, James W.; Crawford, Peter M.; Johnson, Harry R. (March 2004). Strategic significance of America's oil shale resource (PDF). Vol. II: Oil shale resources, technology and economics. DOE. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-21.

- Carter, George William; Jacobsen, Samuel Clark; Mackintosh, Helen Winchester Youngberg (1939). Low-temperature carbonization of Utah coals: a report of the Utah conservation and research foundation to the governor and state Legislature. Quality press.

- EPA Oil Shale Research Group (1979). EPA Program Status Report. Oil shale. Interagency energy-environment research and development program report. EPA.

- Lee, Sunggyu (1990). Oil Shale Technology. CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-4615-0.

- Merrow, Edward W. (2006). Constraints on the commercialization of oil shale (PDF). The RAND Corporation. ISBN 978-0-8330-0037-8.

- Office of Technology Assessment (June 1980). An Assessment of Oil Shale Technologies (PDF). Diane Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-4289-2463-5. NTIS order #PB80-210115.

- Oil shale in the United States

- Energy history of the United States

- Environmental issues in the United States

- History of science and technology in the United States

- Industry in the United States

- Mining in the United States

- Natural gas fields in the United States

- Petroleum in the United States

- Water pollution in the United States