Complex-differentiable (mathematical) function For Zariski's theory of holomorphic functions on an algebraic variety, see formal holomorphic function. "Holomorphism" redirects here. Not to be confused with Homomorphism.

| Mathematical analysis → Complex analysis |

| Complex analysis |

|---|

|

| Complex numbers |

| Complex functions |

| Basic theory |

| Geometric function theory |

| People |

In mathematics, a holomorphic function is a complex-valued function of one or more complex variables that is complex differentiable in a neighbourhood of each point in a domain in complex coordinate space . The existence of a complex derivative in a neighbourhood is a very strong condition: It implies that a holomorphic function is infinitely differentiable and locally equal to its own Taylor series (is analytic). Holomorphic functions are the central objects of study in complex analysis.

Though the term analytic function is often used interchangeably with "holomorphic function", the word "analytic" is defined in a broader sense to denote any function (real, complex, or of more general type) that can be written as a convergent power series in a neighbourhood of each point in its domain. That all holomorphic functions are complex analytic functions, and vice versa, is a major theorem in complex analysis.

Holomorphic functions are also sometimes referred to as regular functions. A holomorphic function whose domain is the whole complex plane is called an entire function. The phrase "holomorphic at a point " means not just differentiable at , but differentiable everywhere within some close neighbourhood of in the complex plane.

Definition

Given a complex-valued function of a single complex variable, the derivative of at a point in its domain is defined as the limit

This is the same definition as for the derivative of a real function, except that all quantities are complex. In particular, the limit is taken as the complex number tends to , and this means that the same value is obtained for any sequence of complex values for that tends to . If the limit exists, is said to be complex differentiable at . This concept of complex differentiability shares several properties with real differentiability: It is linear and obeys the product rule, quotient rule, and chain rule.

A function is holomorphic on an open set if it is complex differentiable at every point of . A function is holomorphic at a point if it is holomorphic on some neighbourhood of . A function is holomorphic on some non-open set if it is holomorphic at every point of .

A function may be complex differentiable at a point but not holomorphic at this point. For example, the function is complex differentiable at , but is not complex differentiable anywhere else, esp. including in no place close to (see the Cauchy–Riemann equations, below). So, it is not holomorphic at .

The relationship between real differentiability and complex differentiability is the following: If a complex function is holomorphic, then and have first partial derivatives with respect to and , and satisfy the Cauchy–Riemann equations:

or, equivalently, the Wirtinger derivative of with respect to , the complex conjugate of , is zero:

which is to say that, roughly, is functionally independent from , the complex conjugate of .

If continuity is not given, the converse is not necessarily true. A simple converse is that if and have continuous first partial derivatives and satisfy the Cauchy–Riemann equations, then is holomorphic. A more satisfying converse, which is much harder to prove, is the Looman–Menchoff theorem: if is continuous, and have first partial derivatives (but not necessarily continuous), and they satisfy the Cauchy–Riemann equations, then is holomorphic.

Terminology

The term holomorphic was introduced in 1875 by Charles Briot and Jean-Claude Bouquet, two of Augustin-Louis Cauchy's students, and derives from the Greek ὅλος (hólos) meaning "whole", and μορφή (morphḗ) meaning "form" or "appearance" or "type", in contrast to the term meromorphic derived from μέρος (méros) meaning "part". A holomorphic function resembles an entire function ("whole") in a domain of the complex plane while a meromorphic function (defined to mean holomorphic except at certain isolated poles), resembles a rational fraction ("part") of entire functions in a domain of the complex plane. Cauchy had instead used the term synectic.

Today, the term "holomorphic function" is sometimes preferred to "analytic function". An important result in complex analysis is that every holomorphic function is complex analytic, a fact that does not follow obviously from the definitions. The term "analytic" is however also in wide use.

Properties

Because complex differentiation is linear and obeys the product, quotient, and chain rules, the sums, products and compositions of holomorphic functions are holomorphic, and the quotient of two holomorphic functions is holomorphic wherever the denominator is not zero. That is, if functions and are holomorphic in a domain , then so are , , , and . Furthermore, is holomorphic if has no zeros in ; otherwise it is meromorphic.

If one identifies with the real plane , then the holomorphic functions coincide with those functions of two real variables with continuous first derivatives which solve the Cauchy–Riemann equations, a set of two partial differential equations.

Every holomorphic function can be separated into its real and imaginary parts , and each of these is a harmonic function on (each satisfies Laplace's equation ), with the harmonic conjugate of . Conversely, every harmonic function on a simply connected domain is the real part of a holomorphic function: If is the harmonic conjugate of , unique up to a constant, then is holomorphic.

Cauchy's integral theorem implies that the contour integral of every holomorphic function along a loop vanishes:

Here is a rectifiable path in a simply connected complex domain whose start point is equal to its end point, and is a holomorphic function.

Cauchy's integral formula states that every function holomorphic inside a disk is completely determined by its values on the disk's boundary. Furthermore: Suppose is a complex domain, is a holomorphic function and the closed disk is completely contained in . Let be the circle forming the boundary of . Then for every in the interior of :

where the contour integral is taken counter-clockwise.

The derivative can be written as a contour integral using Cauchy's differentiation formula:

for any simple loop positively winding once around , and

for infinitesimal positive loops around .

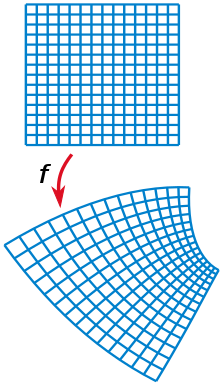

In regions where the first derivative is not zero, holomorphic functions are conformal: they preserve angles and the shape (but not size) of small figures.

Every holomorphic function is analytic. That is, a holomorphic function has derivatives of every order at each point in its domain, and it coincides with its own Taylor series at in a neighbourhood of . In fact, coincides with its Taylor series at in any disk centred at that point and lying within the domain of the function.

From an algebraic point of view, the set of holomorphic functions on an open set is a commutative ring and a complex vector space. Additionally, the set of holomorphic functions in an open set is an integral domain if and only if the open set is connected. In fact, it is a locally convex topological vector space, with the seminorms being the suprema on compact subsets.

From a geometric perspective, a function is holomorphic at if and only if its exterior derivative in a neighbourhood of is equal to for some continuous function . It follows from

that is also proportional to , implying that the derivative is itself holomorphic and thus that is infinitely differentiable. Similarly, implies that any function that is holomorphic on the simply connected region is also integrable on .

(For a path from to lying entirely in , define ; in light of the Jordan curve theorem and the generalized Stokes' theorem, is independent of the particular choice of path , and thus is a well-defined function on having or .

Examples

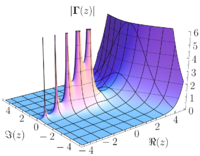

All polynomial functions in with complex coefficients are entire functions (holomorphic in the whole complex plane ), and so are the exponential function and the trigonometric functions and (cf. Euler's formula). The principal branch of the complex logarithm function is holomorphic on the domain . The square root function can be defined as and is therefore holomorphic wherever the logarithm is. The reciprocal function is holomorphic on . (The reciprocal function, and any other rational function, is meromorphic on .)

As a consequence of the Cauchy–Riemann equations, any real-valued holomorphic function must be constant. Therefore, the absolute value , the argument , the real part and the imaginary part are not holomorphic. Another typical example of a continuous function which is not holomorphic is the complex conjugate (The complex conjugate is antiholomorphic.)

Several variables

The definition of a holomorphic function generalizes to several complex variables in a straightforward way. A function in complex variables is analytic at a point if there exists a neighbourhood of in which is equal to a convergent power series in complex variables; the function is holomorphic in an open subset of if it is analytic at each point in . Osgood's lemma shows (using the multivariate Cauchy integral formula) that, for a continuous function , this is equivalent to being holomorphic in each variable separately (meaning that if any coordinates are fixed, then the restriction of is a holomorphic function of the remaining coordinate). The much deeper Hartogs' theorem proves that the continuity assumption is unnecessary: is holomorphic if and only if it is holomorphic in each variable separately.

More generally, a function of several complex variables that is square integrable over every compact subset of its domain is analytic if and only if it satisfies the Cauchy–Riemann equations in the sense of distributions.

Functions of several complex variables are in some basic ways more complicated than functions of a single complex variable. For example, the region of convergence of a power series is not necessarily an open ball; these regions are logarithmically-convex Reinhardt domains, the simplest example of which is a polydisk. However, they also come with some fundamental restrictions. Unlike functions of a single complex variable, the possible domains on which there are holomorphic functions that cannot be extended to larger domains are highly limited. Such a set is called a domain of holomorphy.

A complex differential -form is holomorphic if and only if its antiholomorphic Dolbeault derivative is zero: .

Extension to functional analysis

Main article: infinite-dimensional holomorphyThe concept of a holomorphic function can be extended to the infinite-dimensional spaces of functional analysis. For instance, the Fréchet or Gateaux derivative can be used to define a notion of a holomorphic function on a Banach space over the field of complex numbers.

See also

- Antiderivative (complex analysis)

- Antiholomorphic function

- Biholomorphy

- Cauchy's estimate

- Harmonic maps

- Harmonic morphisms

- Holomorphic separability

- Meromorphic function

- Quadrature domains

- Wirtinger derivatives

Footnotes

- The original French terms were holomorphe and méromorphe:

Briot & Bouquet (1875), pp. 14–15; see also Harkness & Morley (1893), p. 161.Lorsqu'une fonction est continue, monotrope, et a une dérivée, quand la variable se meut dans une certaine partie du plan, nous dirons qu'elle est holomorphe dans cette partie du plan. Nous indiquons par cette dénomination qu'elle est semblable aux fonctions entières qui jouissent de ces propriétés dans toute l'étendue du plan.

Une fraction rationnelle admet comme pôles les racines du dénominateur; c'est une fonction holomorphe dans toute partie du plan qui ne contient aucun de ses pôles.

Lorsqu'une fonction est holomorphe dans une partie du plan, excepté en certains pôles, nous dirons qu'elle est méromorphe dans cette partie du plan, c'est-à-dire semblable aux fractions rationnelles.

plane, we say that it is holomorphic in that part of the plane. We mean by this name that it resembles entire functions which enjoy these properties in the full extent of the plane. ...

- Briot & Bouquet (1859), p. 11 had previously also adopted Cauchy's term synectic (synectique in French), in the first edition of their book.

References

- "Analytic functions of one complex variable". Encyclopedia of Mathematics. European Mathematical Society / Springer. 2015 – via encyclopediaofmath.org.

- "Analytic function", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 , retrieved February 26, 2021

- Ahlfors, L., Complex Analysis, 3 ed. (McGraw-Hill, 1979).

- Henrici, P. (1986) . Applied and Computational Complex Analysis. Wiley. Three volumes, publ.: 1974, 1977, 1986.

- Ebenfelt, Peter; Hungerbühler, Norbert; Kohn, Joseph J.; Mok, Ngaiming; Straube, Emil J. (2011). Complex Analysis. Science & Business Media. Springer. ISBN 978-3-0346-0009-5 – via Google.

- ^ Markushevich, A.I. (1965). Theory of Functions of a Complex Variable. Prentice-Hall.

- ^ Gunning, Robert C.; Rossi, Hugo (1965). Analytic Functions of Several Complex Variables. Modern Analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 9780821869536. MR 0180696. Zbl 0141.08601 – via Google.

- Gray, J.D.; Morris, S.A. (April 1978). "When is a function that satisfies the Cauchy-Riemann equations analytic?". The American Mathematical Monthly. 85 (4): 246–256. doi:10.2307/2321164. JSTOR 2321164.

- ^ Briot, C.A.; Bouquet, J.-C. (1875). "§15 fonctions holomorphes". Théorie des fonctions elliptiques [Theory of the Elliptical Functions] (in French) (2nd ed.). Gauthier-Villars. pp. 14–15.

- ^ Harkness, James; Morley, Frank (1893). "5. Integration". A Treatise on the Theory of Functions. Macmillan. p. 161.

- Briot, C.A.; Bouquet, J.-C. (1859). "§10". Théorie des fonctions doublement périodiques. Mallet-Bachelier. p. 11.

- Henrici, Peter (1993) . Applied and Computational Complex Analysis. Wiley Classics Library. Vol. 3 (Reprint ed.). New York - Chichester - Brisbane - Toronto - Singapore: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-58986-1. MR 0822470. Zbl 1107.30300 – via Google.

- Evans, L.C. (1998). Partial Differential Equations. American Mathematical Society.

- ^ Lang, Serge (2003). Complex Analysis. Springer Verlag GTM. Springer Verlag.

- Rudin, Walter (1987). Real and Complex Analysis (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw–Hill Book Co. ISBN 978-0-07-054234-1. MR 0924157.

- Gunning and Rossi. Analytic Functions of Several Complex Variables. p. 2.

Further reading

- Blakey, Joseph (1958). University Mathematics (2nd ed.). London, UK: Blackie and Sons. OCLC 2370110.

(bottom).

(bottom). . The animation shows different

. The animation shows different  in blue color with the corresponding

in blue color with the corresponding  in red color. The point

in red color. The point  . y-axis represents the imaginary part of the complex number of

. y-axis represents the imaginary part of the complex number of  . The existence of a complex derivative in a neighbourhood is a very strong condition: It implies that a holomorphic function is

. The existence of a complex derivative in a neighbourhood is a very strong condition: It implies that a holomorphic function is  " means not just differentiable at

" means not just differentiable at  is not complex differentiable at zero, because as shown above, the value of

is not complex differentiable at zero, because as shown above, the value of  varies depending on the direction from which zero is approached. On the real axis only,

varies depending on the direction from which zero is approached. On the real axis only,  and the limit is

and the limit is  , while along the imaginary axis only,

, while along the imaginary axis only,  and the limit is

and the limit is  . Other directions yield yet other limits.

. Other directions yield yet other limits.

if it is complex differentiable at every point of

if it is complex differentiable at every point of  if it is holomorphic at every point of

if it is holomorphic at every point of  is complex differentiable at

is complex differentiable at  , but is not complex differentiable anywhere else, esp. including in no place close to

, but is not complex differentiable anywhere else, esp. including in no place close to  is holomorphic, then

is holomorphic, then  and

and  have first partial derivatives with respect to

have first partial derivatives with respect to  and

and  , and satisfy the

, and satisfy the

, the

, the

are holomorphic in a domain

are holomorphic in a domain  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . Furthermore,

. Furthermore,  is holomorphic if

is holomorphic if  with the real

with the real  , then the holomorphic functions coincide with those functions of two real variables with continuous first derivatives which solve the

, then the holomorphic functions coincide with those functions of two real variables with continuous first derivatives which solve the  ), with

), with  on a

on a  is the real part of a holomorphic function: If

is the real part of a holomorphic function: If

is a

is a  whose start point is equal to its end point, and

whose start point is equal to its end point, and  is a holomorphic function.

is a holomorphic function.

is

is  . Then for every

. Then for every  in the

in the

can be written as a contour integral using

can be written as a contour integral using

in a neighbourhood

in a neighbourhood  for some continuous function

for some continuous function  . It follows from

. It follows from

is also proportional to

is also proportional to  , implying that the derivative

, implying that the derivative  implies that any function

implies that any function  ; in light of the

; in light of the  is independent of the particular choice of path

is independent of the particular choice of path  is a well-defined function on

is a well-defined function on  or

or  .

.

and the

and the  and

and  (cf.

(cf.  is holomorphic on the domain

is holomorphic on the domain  . The

. The  and is therefore holomorphic wherever the logarithm

and is therefore holomorphic wherever the logarithm  is holomorphic on

is holomorphic on  . (The reciprocal function, and any other

. (The reciprocal function, and any other  , the

, the  , the

, the  and the

and the  are not holomorphic. Another typical example of a continuous function which is not holomorphic is the

are not holomorphic. Another typical example of a continuous function which is not holomorphic is the  (The complex conjugate is

(The complex conjugate is  in

in  complex variables is analytic at a point

complex variables is analytic at a point  if there exists a neighbourhood of

if there exists a neighbourhood of  coordinates are fixed, then the restriction of

coordinates are fixed, then the restriction of  -form

-form is holomorphic if and only if its antiholomorphic

is holomorphic if and only if its antiholomorphic  .

.