| Inguinal hernia surgery | |

|---|---|

Open surgical repair of a right inguinal hernia Open surgical repair of a right inguinal hernia | |

| Specialty | General surgery |

| [edit on Wikidata] | |

| This article's lead section may be too long. Please read the length guidelines and help move details into the article's body. (September 2022) |

Inguinal hernia surgery is an operation to repair a weakness in the abdominal wall that abnormally allows abdominal contents to slip into a narrow tube called the inguinal canal in the groin region.

There are two different clusters of hernia: groin and ventral (abdominal) wall. Groin hernia includes femoral, obturator, and inguinal. Inguinal hernia is the most common type of hernia and consist of about 75% of all hernia surgery cases in the US. Inguinal hernia, which results from lower abdominal wall weakness or defect, is more common among men with about 90% of total cases. In the inguinal hernia, fatty tissue or a part of the small intestine gets inserted into the inguinal canal. Other structures that are uncommon but may get stuck in inguinal hernia can be the appendix, caecum, and transverse colon. Hernias can be asymptomatic, incarcerated, or strangled. Incarcerated hernia leads to impairment of intestinal flow, and strangled hernia obstructs blood flow in addition to intestinal flow.

Inguinal hernia can make a small lump in the groin region which can be detected during a physical exam and verified by imaging techniques such as computed tomography (CT). This lump can disappear by lying down and reappear through physical activities, laughing, crying, or forceful bowel movement. Other symptoms can include pain around the groin, an increase in the size of bulge over the time, pain while lifting, and a dull aching sensation. In occult (hidden) hernia, the bulge cannot be detected by physical examination and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be more helpful in this situation. Males who have asymptomatic inguinal hernia and pregnant women with uncomplicated inguinal hernia can be observed, but the definitive treatment is mostly surgery.

Surgery remains the ultimate treatment for all types of hernias as they will not get better on their own, however not all require immediate repair. Elective surgery is offered to most patients taking into account their level of pain, discomfort, degree of disruption in normal activity, as well as their overall level of health. Emergency surgery is typically reserved for patients with life-threatening complications of inguinal hernias such as incarceration and strangulation. Incarceration occurs when intra-abdominal fat or small intestine becomes stuck within the canal and cannot slide back into the abdominal cavity either on its own or with manual maneuvers. Left untreated, incarceration may progress to bowel strangulation as a result of restricted blood supply to the trapped segment of small intestine causing that portion to die. Successful outcomes of repair are usually measured via rates of hernia recurrence, pain and subsequent quality of life.

Surgical repair of inguinal hernias is one of the most commonly performed operations worldwide and the most commonly performed surgery within the United States. A combined 20 million cases of both inguinal and femoral hernia repair are performed every year around the world with 800,000 cases in the US as of 2003. The UK reports around 70,000 cases performed every year. Groin hernias account for almost 75% of all abdominal wall hernias with the lifetime risk of an inguinal hernia in men and women being 27% and 3% respectively. Men account for nearly 90% of all repairs performed and have a bimodal incidence of inguinal hernias peaking at 1 year of age and again in those over the age of 40. Although women account for roughly 70% of femoral hernia repairs, indirect inguinal hernias are still the most common subtype of groin hernia in both males and females.

Inguinal hernia surgery is also one of the most common surgical procedures, with an estimated incidence of 0.8-2% and increasing up to 20% in preterm children.

Indications for surgery

Surgical intervention for hernias is guided by various factors, including the severity of symptoms, hernia type, medical history, hernia size, bowel incarceration (bowel can no longer return to the abdomen) and the overall general health of the person.

Non-urgent repair

Elective surgery is planned in order to help relieve symptoms, respect the person's preference, and prevent future complications that may require emergency surgery.

Surgery is offered to the majority of people who:

- have symptoms that interfere with their normal level of activity.

- have hernias that become increasingly difficult to reduce.

- are female as it is often difficult to classify the subtype of hernia based on an exam alone.

Symptomatic hernias tend to cause pain or discomfort within the groin region that may increase with exertion and improve with rest. A swollen scrotum within males may coincide with persistent feelings of heaviness or generalized lower abdominal discomfort. The sensation of groin pressure tends to be most prominent at the end of the day as well as after strenuous activities. Changes in sensation may be experienced along the scrotum and inner thigh.

Urgent repair

A hernia in which the small intestine has become incarcerated or strangulated constitutes a surgical emergency. Symptoms include:

- Fever

- Nausea and vomiting

- Extreme pain in the area of the hernia

- Warm hernia bulge with surrounding skin redness

- Can no longer pass gas or stool

Surgical repair within 6 hours of the above symptoms may be able to save the strangulated portion of the intestine.

Although pediatric inguinal hernias sometimes present asymptomatically, surgical repair is still the standard of care to prevent hernia incarceration, which for children who are born with hernias has a risk of 12% in full-term children and 39% in preterm children. In preterm neonates, the timing for intervention appears to be of utter importance as surgical hernia repair after neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) discharge might decrease recurrence and anesthesia-induced respiratory difficulties compared to surgery before NICU discharge.

Contraindications to surgery

The person with the hernia should be given an opportunity to participate in the shared decision-making with their physicians as almost all procedures carry significant risks. The benefits of inguinal hernia repair can become overshadowed by risks such that elective repair is no longer in a person's best interest. Such cases include:

- People with unstable medical conditions

- Repair using mesh is withheld if a person has an active infection within the groin or within the blood stream

- Elective repair is delayed in pregnant women until 4 weeks after delivery

Additionally, certain medical conditions can prevent people from being candidates for laparoscopic approaches to repair. Examples of such include:

- People who are unable to undergo general anesthesia

- Prior major open abdominal surgery

- People who have ascites

- Previous radiation therapy to the pelvis

- A complex hernia

Surgical approaches

Techniques to repair inguinal hernias fall into two broad categories termed "open" and "laparoscopic". Surgeons tailor their approach by taking into account factors such as their own experience with either techniques, the features of the hernia itself, and the person's anesthetic needs.

The cost associated with either approach varies widely across regions, but updated guidelines published by the International Endohernia Society (IES) cast doubt on the comprehensiveness of cost comparison studies due in part to the complexity inherent in calculating costs across institutions. The IES asserts that hospital and societal costs are lower for laparoscopic repairs as compared to open approaches. They recommend the routine use of reusable instruments as well as improving the proficiency of surgeons to help further decrease costs as well as time spent in the OR. However, as an example, the UK's National Health Service spends £56 million a year in repairing inguinal hernias, 96% of which were repaired via the open mesh approach while only 4% were done laparoscopically.

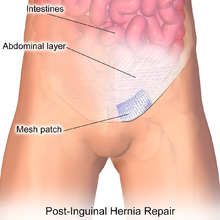

Open hernia repair

All techniques involve an approximate 10-cm incision in the groin. Once exposed, the hernia sac is returned to the abdominal cavity or excised and the abdominal wall is very often reinforced with mesh. There are many techniques that do not utilize mesh and have their own situations where they are preferable.

Open repairs are classified via whether prosthetic mesh is utilized or whether the patient's own tissue is used to repair the weakness. Prosthetic repairs enable surgeons to repair a hernia without causing undue tension in the surrounding tissues while reinforcing the abdominal wall. Repairs with undue tension have been shown to increase the likelihood that the hernia will recur. Repairs not using prosthetic mesh are preferable options in patients with an above-average risk of infection such as cases where the bowel has become strangulated (blood supply lost due to constriction).

One large benefit of this approach lies in its ability to tailor anesthesia to a person's needs. People can be administered local anesthesia, a spinal block, as well as general anesthesia. Local anesthesia has been shown to cause less pain after surgery, shorten operating times, shorten recovery times as well as decrease the need to return to the hospital. However, people who undergo general anesthesia tend to be able to go home faster and experience fewer complications. The European Hernia Society recommends the use of local anesthesia particularly for people with ongoing medical conditions.

Open mesh repairs

Repairs that utilize mesh are usually the first recommendation for the vast majority of patients including those that undergo laparoscopic repair. Procedures that employ mesh are the most commonly performed as they have been able to demonstrate better results compared to non-mesh repairs. Approaches utilizing mesh have been able to demonstrate faster return to usual activity, lower rates of persistent pain, shorter hospital stays, and a lower likelihood that the hernia will recur.

Options for mesh include either synthetic or biologic. Synthetic mesh provides the option of using "heavyweight" as well as "lightweight" variations according to the diameter and number of mesh fibers. Lightweight mesh has been shown to have fewer complications related to the mesh itself than its heavyweight counterparts. It was additionally correlated with lower rates of chronic pain while sharing the same rates of hernia recurrence as compared to heavyweight options. This has led to the adoption of lightweight mesh for minimizing the chance of chronic pain after surgery. Biologic mesh is indicated in cases where the risk of infection is a major concern such as cases in which the bowel has become strangulated. They tend to have lower tensile strength than their synthetic counterparts lending them to higher rates of mesh rupture.

Biomeshes are increasingly popular since their first use in 1999 and their subsequent introduction to the market in 2003. Some have a similar price to high end synthetic meshes. They can be produced from absorbable, animal-sourced extra cellular matrix, or by other means. Synthetic absorbable meshes are also available.

Meshes made of mosquito net cloth, in copolymer of polyethylene and polypropylene have been used for low-income patients in rural India and Ghana. Each piece costs $0.01, 3700 times cheaper than an equivalent commercial mesh. They give results identical to commercial meshes in terms of infection and recurrence rate at 5 years.

Lichtenstein technique

The Lichtenstein tension-free repair has persisted as one of the most commonly performed procedures in the world. The European Hernia Society recommends that in cases where an open approach is indicated, the Lichtenstein technique be utilized as the preferred method. Recent studies have indicated that mesh attachment with the use of adhesive glue is faster and less likely to cause post-op pain as compared to attachment via suture material.

Plug and patch technique

The plug and patch tension-free technique has fallen out of favor due to higher rates of mesh shift along with its tendency to irritate surrounding tissue. This has led to the European Hernia Society recommending that the technique not be used in most cases.

Other open mesh repair techniques

A variety of other tension-free techniques have been developed and include:

- Prolene mesh system (PHS)

- Kugel (preperitoneal repair)

- Stoppa

- Trabucco (Hertra mesh)

- Wantz

- Rutkow/Robbins

- Modified APP

Open non-mesh repairs

Techniques in which mesh is not used are referred to as tissue repair technique, suture technique, and tension technique. All involve bringing together the tissue with sutures and are a viable alternative when mesh placement is contraindicated. Such situations are most commonly due to concerns of contamination in cases where there are infections of the groin, strangulation or perforation of the bowel.

Shouldice technique

The Shouldice technique is the most effective non-mesh repair thus making it one of the most commonly utilized methods. Numerous studies have been able to validate the conclusion that patients have lower rates of hernia recurrence with the Shouldice technique as compared to other non-mesh repair techniques. However this method frequently experiences longer procedure times and length of hospital stay. Despite being the superior non-mesh technique, the Shouldice method results much higher rates of hernia recurrence in patients when compared to repairs that utilize mesh.

Bassini technique

The Bassini technique, described by Edoardo Bassini in the 1880s, was the first efficient inguinal hernia repair. In this technique, the conjoint tendon (formed by the distal ends of the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles) is approximated to the inguinal ligament and closed.

Other open non-mesh techniques

The Shouldice technique was itself an evolution of prior techniques that had greatly advanced the field of inguinal hernia surgery. Such classic open non-mesh repairs include:

- McVay technique

- Halsted

- Maloney darn

- Plication darn

- Desarda technique A 1–2 cm strip of the external oblique aponeurosis is stitched below to the inguinal ligament and above to the muscle arch without disturbing its continuity at either end. This gives immediate protection, so no restrictions on activities are required. The procedures results in very low recurrence and complication rates.

Laparoscopic repair

There are two main methods of laparoscopic repair: transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) and totally extra-peritoneal (TEP) repair. When performed by a surgeon experienced in hernia repair, laparoscopic repair causes fewer complications than Lichtenstein, particularly less chronic pain. However, if the surgeon is experienced in general laparoscopic surgery but not in the specific subject of laparoscopic hernia surgery, laparoscopic repair is not advised as it causes more recurrence risk than Lichtenstein while also presenting risks of serious complications, as organ injury. All that said, many surgeons are shifting to using laparoscopic techniques as they require smaller incisions, and result in less bleeding, lower infection rates, faster recovery, shorter hospitalization periods, and reduced chronic pain.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

|

|

Recurrence rates are identical when laparoscopy is performed by an experienced surgeon. When performed by a surgeon less experienced in inguinal hernia lap repair, recurrence is larger than after Lichtenstein.

Robotic surgery

Robot assisted repair of inguinal hernias has demonstrated safety and efficacy in surgeries repairing inguinal hernias that present on both sides of the pubic bone (bilateral) as well as inguinal hernias that present on one side (unilateral). In comparing robot assisted repair of inguinal hernias to traditional laparoscopic techniques, robot assisted surgeries repairing inguinal hernias have longer operating times and can be more costly. However, measures of safety, complication rates, and readmission rates did not significantly differ between robot assisted repair and traditional laparoscopic repair.

Non-surgical management

Studies have demonstrated that men whose hernias cause little to no symptoms can safely continue to delay surgery until a time that is most convenient for patients and their healthcare team. Research shows that the risk of inguinal hernia complications remains under 1% within the population. Watchful waiting requires that patients maintain a close follow-up schedule with providers to monitor the course of their hernia for any changes in symptoms and can be safely offered for up to 2 years.

Patients who do elect watchful waiting eventually undergo repair within five years as 25% will experience a progression of symptoms such as worsening of pain. Elective repair discussions should be revisited if patients begin to avoid aspects of their normal routine due to their hernia. After 1 year it is estimated that 16% of patients who initially opted for watchful waiting will eventually undergo surgery. Furthermore, 54% and 72% will undergo repair at 5-year and 7.5-year marks respectively.

The use of a truss is an additional non-surgical option for men. It resembles a jock-strap that utilizes a pad to exert pressure at the site of the hernia in order prevent excursion of the hernia sack. It has little evidence to support its routine use and has not been shown to prevent complications such as incarceration (bowel can no longer slide back into abdomen) or strangulation of bowel (constriction causing loss of blood supply). However some patients do report a soothing of symptoms when utilized.

Complications and prognosis

Inguinal hernia repair complications are unusual, and the procedure as a whole proves to be relatively safe for the majority of patients. Risks inherent in almost all surgical procedures include:

- bleeding

- infection

- fluid collections

- damage to surrounding structures such as blood vessels, nerves, or the bladder

- urinary retention requiring a catheter

- risks of general anaesthetic (used for laparoscopic hernia repair and most open hernia repairs)

Risks that are specific to inguinal hernia repairs include such things as:

- recurrence of the hernia

- impairment of sexual activity, such as genital or ejaculatory pain

- in males, injury to the tube that conveys sperm from the testicle to the penis

- in males, bruising and swelling of the scrotum

- chronic regional pain (also known as post-herniorrhaphy inguinodynia, or chronic postoperative inguinal pain)

Post-herniorraphy pain syndrome

Post-herniorrhaphy inguinodynia is a condition where 10-12% of patients experience severe pain after inguinal hernia repair, due to a complex combination of different forms of pain signals. It can occur with any inguinal hernia repair technique, and if unresponsive to pain medications, further surgical intervention is often required. Removal of the implanted mesh, in combination with bisection of regional nerves, is commonly performed to address such cases. There remains ongoing discussion amongst surgeons regarding the utility of planned resections of regional nerves as an attempt to prevent its occurrence.

Mortality rates

Mortality rates for non-urgent, elective procedures was demonstrated as 0.1%, and around 3% for procedures performed urgently. Other than urgent repair, risk factors that were also associated with increased mortality included being female, requiring a femoral hernia repair, and older age.

Follow-up

Upon awakening from anesthesia, patients are monitored for their ability to drink fluids, produce urine, as well as their ability to walk after surgery. Most patients are then able to return home once those conditions are met. It is not uncommon for patients to experience residual soreness for a couple of days after surgery. Patients are encouraged to make strong efforts in getting up and walking around the day after surgery. Most patients can resume their normal routine of daily living within the week such as driving, showering, light lifting, as well as sexual activity. Long work absences are rarely necessary and length of sick days tend to be dictated by respective employment policies.

In general, it is not recommended to administer antibiotics as prophylaxis after elective inguinal hernia repair. However, the rate of wound infection determines the appropriate use of the antibiotics.

Post-op development of any of the following should warrant timely reporting via phone:

- fever greater than 39C/101F

- progressive swelling of the surgical site

- severe pain

- recurring nausea or vomiting

- worsening redness around incisions

- drainage of pus from incisions

- difficulty or lack of producing urine

- new-onset shortness of breath

Prevention and screening

Most indirect inguinal hernias in the abdominal wall are not preventable. Direct inguinal hernias may be prevented by maintaining a healthy weight, refraining from smoking, preventing straining during bowel movements, and maintaining proper lifting techniques when heavy lifting. There is no evidence that indicates physicians should routinely screen for asymptomatic inguinal hernias during patient visits.

References

- ^ "About Hernias | Hernia Surgery | SUNY Upstate Medical University". www.upstate.edu. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- "Inguinal Hernia: Types, Causes, Symptoms & Treatment". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- ^ Rather, Assar A. (16 March 2023). "Abdominal Hernias: Practice Essentials, Background, Anatomy". Medscape. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- Shakil, Amer; Aparicio, Kimberly; Barta, Elizabeth; Munez, Kristal (2020-10-15). "Inguinal Hernias: Diagnosis and Management". American Family Physician. 102 (8): 487–492. ISSN 1532-0650. PMID 33064426.

- ^ "Hernia: Types, Treatments, Symptoms, Causes & Prevention". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- Koirala, Dinesh Prasad; Joshi, Surya Prakash; Timilsina, Sujan; Shress, Vijay; Gc, Saroj; Sharma, Sujan (March 2022). "Large intestine as content of congenital inguinal hernia: A case report of intestinal obstruction". Annals of Medicine and Surgery (2012). 75: 103396. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103396. ISSN 2049-0801. PMC 8977924. PMID 35386764.

- Miller, Joseph; Cho, Janice; Michael, Meina Joseph; Saouaf, Rola; Towfigh, Shirin (2014-10-01). "Role of Imaging in the Diagnosis of Occult Hernias". JAMA Surgery. 149 (10): 1077–1080. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2014.484. ISSN 2168-6254. PMID 25141884.

- "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- ^ Hewitt, D. Brock (2017-06-27). "Groin Hernia". JAMA. 317 (24): 2560. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.1556. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 28655018.

- ^ "Overview of treatment for inguinal and femoral hernia in adults". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 2017-12-14.

- ^ "Inguinal Hernia | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved 2017-12-01.

- ^ "World Guidelines for Hernia Management" (PDF). European Hernia Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 6, 2017. Retrieved December 1, 2017.

- ^ "Laparoscopic surgery for inguinal hernia repair | Guidance and guidelines | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. 22 September 2004. Retrieved 2017-12-05.

- P. Wagner, Justin; Brunicardi, F. Charles; Amid, Parviz K.; Chen, David C. (2014). "Inguinal Hernias". In Brunicardi, F. Charles; Andersen, Dana K.; Billiar, Timothy R.; Dunn, David L.; Hunter, John G.; Matthews, Jeffrey B.; Pollock, Raphael E. (eds.). Schwartz's Principles of Surgery (10 ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Rajput, Ashwani; Gauderer, Michael W.L.; Hack, Maureen (October 1992). "Inguinal hernias in very low birth weight infants: Incidence and timing of repair". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 27 (10): 1322–1324. doi:10.1016/0022-3468(92)90287-h. ISSN 0022-3468. PMID 1403513.

- Kumar, Vasantha H. S.; Clive, Jonathan; Rosenkrantz, Ted S.; Bourque, Michael D.; Hussain, Naveed (2002-03-01). "Inguinal hernia in preterm infants (≤32-Week Gestation)". Pediatric Surgery International. 18 (2–3): 147–152. doi:10.1007/s003830100631. ISSN 0179-0358. PMID 11956782. S2CID 1482347.

- ^ "Inguinal Hernia Repair Surgery Information from SAGES". SAGES. Retrieved 2017-12-05.

- "Laparoscopic surgery for inguinal hernia repair | Guidance and guidelines | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. 22 September 2004. Retrieved 2017-12-05.

- ^ DynaMed Plus . Ipswich (MA): EBSCO Information Services. 1995 - . Record No. 113880, Groin hernia in adults and adolescents; ; . Available from http://www.dynamed.com/login.aspx?direct=true&site=DynaMed&id=113880 Archived 2021-06-21 at the Wayback Machine . Registration and login required.

- ^ "Inguinal hernia - Diagnosis and treatment - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2017-12-05.

- ^ Wagner, Justin; Brunicardi; Amid; Chen (2015). "Inguinal Hernias". Schwartz's Principles of Surgery, 10e. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07179674-3.

- Chang, S.-J.; Chen, J. Y.-C.; Hsu, C.-K.; Chuang, F.-C.; Yang, S. S.-D. (2015-11-30). "The incidence of inguinal hernia and associated risk factors of incarceration in pediatric inguinal hernia: a nation-wide longitudinal population-based study". Hernia. 20 (4): 559–563. doi:10.1007/s10029-015-1450-x. ISSN 1265-4906. PMID 26621139. S2CID 4242082.

- Masoudian, Pourya; Sullivan, Katrina J; Mohamed, Hisham; Nasr, Ahmed (August 2019). "Optimal timing for inguinal hernia repair in premature infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 54 (8): 1539–1545. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.11.002. PMID 30541673. S2CID 56144553.

- Bittner, R.; Montgomery, M. A.; Arregui, E.; Bansal, V.; Bingener, J.; Bisgaard, T.; Buhck, H.; Dudai, M.; Ferzli, G. S. (2015). "Update of guidelines on laparoscopic (TAPP) and endoscopic (TEP) treatment of inguinal hernia (International Endohernia Society)". Surgical Endoscopy. 29 (2): 289–321. doi:10.1007/s00464-014-3917-8. ISSN 0930-2794. PMC 4293469. PMID 25398194.

- ^ Hewitt, D. Brock; Chojnacki, Karen (2017-08-22). "Groin Hernia Repair by Open Surgery". JAMA. 318 (8): 764. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.9868. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 28829878.

- Nordin, Pär; Zetterström, Henrik; Gunnarsson, Ulf; Nilsson, Erik (2003-09-13). "Local, regional, or general anaesthesia in groin hernia repair: multicentre randomised trial". Lancet. 362 (9387): 853–858. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14339-5. ISSN 1474-547X. PMID 13678971. S2CID 46146950.

- van Veen, Ruben N.; Mahabier, Chander; Dawson, Imro; Hop, Wim C.; Kok, Niels F. M.; Lange, Johan F.; Jeekel, Johannus (March 2008). "Spinal or local anesthesia in lichtenstein hernia repair: a randomized controlled trial". Annals of Surgery. 247 (3): 428–433. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e318165b0ff. ISSN 0003-4932. PMID 18376185. S2CID 22487510.

- "Inguinal Hernia". Blausen Medical. Retrieved 27 January 2016.(subscription required)

- ^ Scott, N. W.; McCormack, K.; Graham, P.; Go, P. M.; Ross, S. J.; Grant, A. M. (2002). "Open mesh versus non-mesh for repair of femoral and inguinal hernia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD002197. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002197. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 12519568. S2CID 73179502.

- Rosenberg, Jacob; Bisgaard, Thue; Kehlet, Henrik; Wara, Pål; Asmussen, Torsten; Juul, Poul; Strand, Lasse; Andersen, Finn Heidmann; Bay-Nielsen, Morten (February 2011). "Danish Hernia Database recommendations for the management of inguinal and femoral hernia in adults". Danish Medical Bulletin. 58 (2): C4243. ISSN 1603-9629. PMID 21299930.

- Bay-Nielsen, M.; Kehlet, H.; Strand, L.; Malmstrøm, J.; Andersen, F. H.; Wara, P.; Juul, P.; Callesen, T.; Danish Hernia Database Collaboration (2001-10-06). "Quality assessment of 26,304 herniorrhaphies in Denmark: a prospective nationwide study". Lancet. 358 (9288): 1124–1128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06251-1. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 11597665. S2CID 20023648.

- Matthews, Richard D.; Anthony, Thomas; Kim, Lawrence T.; Wang, Jia; Fitzgibbons, Robert J.; Giobbie-Hurder, Anita; Reda, Domenic J.; Itani, Kamal M. F.; Neumayer, Leigh A. (November 2007). "Factors associated with postoperative complications and hernia recurrence for patients undergoing inguinal hernia repair: a report from the VA Cooperative Hernia Study Group". American Journal of Surgery. 194 (5): 611–617. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.07.018. ISSN 1879-1883. PMID 17936422.

- EU Hernia Trialists Collaboration (March 2002). "Repair of groin hernia with synthetic mesh: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Annals of Surgery. 235 (3): 322–332. doi:10.1097/00000658-200203000-00003. ISSN 0003-4932. PMC 1422456. PMID 11882753.

- Earle, David B.; Mark, Lisa A. (February 2008). "Prosthetic material in inguinal hernia repair: how do I choose?". The Surgical Clinics of North America. 88 (1): 179–201, x. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2007.11.002. ISSN 0039-6109. PMID 18267169.

- Bittner, R.; Arregui, M. E.; Bisgaard, T.; Dudai, M.; Ferzli, G. S.; Fitzgibbons, R. J.; Fortelny, R. H.; Klinge, U.; Kockerling, F. (September 2011). "Guidelines for laparoscopic (TAPP) and endoscopic (TEP) treatment of inguinal hernia [International Endohernia Society (IEHS)]". Surgical Endoscopy. 25 (9): 2773–2843. doi:10.1007/s00464-011-1799-6. ISSN 1432-2218. PMC 3160575. PMID 21751060.

- Sajid, Muhammad S.; Kalra, Lorain; Parampalli, Umesh; Sains, Parv S.; Baig, Mirza K. (June 2013). "A systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the effectiveness of lightweight mesh against heavyweight mesh in influencing the incidence of chronic groin pain following laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair". American Journal of Surgery. 205 (6): 726–736. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.07.046. ISSN 1879-1883. PMID 23561639.

- Sajid, M. S.; Leaver, C.; Baig, M. K.; Sains, P. (January 2012). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of lightweight versus heavyweight mesh in open inguinal hernia repair". The British Journal of Surgery. 99 (1): 29–37. doi:10.1002/bjs.7718. ISSN 1365-2168. PMID 22038579. S2CID 30352245.

- Bittner, R.; Montgomery, M. A.; Arregui, E.; Bansal, V.; Bingener, J.; Bisgaard, T.; Buhck, H.; Dudai, M.; Ferzli, G. S. (2015-02-01). "Update of guidelines on laparoscopic (TAPP) and endoscopic (TEP) treatment of inguinal hernia (International Endohernia Society)". Surgical Endoscopy. 29 (2): 289–321. doi:10.1007/s00464-014-3917-8. ISSN 0930-2794. PMC 4293469. PMID 25398194.

- Smart, Neil J.; Bloor, Stephen (September 2012). "Durability of biologic implants for use in hernia repair: a review". Surgical Innovation. 19 (3): 221–229. doi:10.1177/1553350611429027. ISSN 1553-3514. PMID 22143748. S2CID 46476058.

- Edelman, DS; Hodde, JP (2006). "Bioactive prosthetic material for treatment of hernias". Surgical Technology International. 15: 104–8. PMID 17029169.

- Clarke, M. G.; Oppong, C.; Simmermacher, R.; Park, K.; Kurzer, M.; Vanotoo, L.; Kingsnorth, A. N. (2008). "The use of sterilised polyester mosquito net mesh for inguinal hernia repair in Ghana". Hernia. 13 (2): 155–9. doi:10.1007/s10029-008-0460-3. PMID 19089526. S2CID 24486232.

- ^ Tongaonkar, Ravindranath R.; Reddy, Brahma V.; Mehta, Virendra K.; Singh, Ningthoujam Somorjit; Shivade, Sanjay (2003). "Preliminary Multicentric Trial of Cheap Indigenous Mosquito-Net Cloth for Tension-free Hernia Repair". Indian Journal of Surgery. 65 (1): 89–95.

- Wilhelm, T.J.; Freudenberg, S.; Jonas, E.; Grobholz, R.; Post, S.; Kyamanywa, P. (2007). "Sterilized Mosquito Net versus Commercial Mesh for Hernia Repair". European Surgical Research. 39 (5): 312–7. doi:10.1159/000104402. PMID 17595545. S2CID 44820282.

- Sun, Ping; Cheng, Xiang; Deng, Shichang; Hu, Qinggang; Sun, Yi; Zheng, Qichang (7 Feb 2017). "Mesh fixation with glue versus suture for chronic pain and recurrence in Lichtenstein inguinal hernioplasty". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (2): CD010814. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010814.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6464532. PMID 28170080.

- de Goede, B.; Klitsie, P. J.; van Kempen, B. J. H.; Timmermans, L.; Jeekel, J.; Kazemier, G.; Lange, J. F. (May 2013). "Meta-analysis of glue versus sutured mesh fixation for Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair". The British Journal of Surgery. 100 (6): 735–742. doi:10.1002/bjs.9072. ISSN 1365-2168. PMID 23436683. S2CID 20338940.

- Shen, Ying-mo; Sun, Wen-bing; Chen, Jie; Liu, Su-jun; Wang, Ming-gang (April 2012). "NBCA medical adhesive (n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate) versus suture for patch fixation in Lichtenstein inguinal herniorrhaphy: a randomized controlled trial". Surgery. 151 (4): 550–555. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2011.09.031. ISSN 1532-7361. PMID 22088820.

- Reinhorn M. Minimally invasive open preperitoneal inguinal hernia repair. J Med Ins. 2014;2014(8). doi:https://doi.org/10.24296/jomi/8

- ^ Amato, Bruno; Moja, Lorenzo; Panico, Salvatore; Persico, Giovanni; Rispoli, Corrado; Rocco, Nicola; Moschetti, Ivan (2012-04-18). "Shouldice technique versus other open techniques for inguinal hernia repair". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012 (4): CD001543. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001543.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6465190. PMID 22513902.

- doctor/3213 at Who Named It?

- Bassini E, Nuovo metodo operativo per la cura dell'ernia inguinale. Padua, 1889.

- Gordon, T. L. (1945). "Bassini's Operation for Inguinal Hernia". BMJ. 2 (4414): 181–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4414.181. PMC 2059571. PMID 20786215.

- ""INGUINAL HERNIA REPAIR WITHOUT MESH"-"DESARDA REPAIR"". www.desarda.com. Retrieved 2017-12-10.

- Desarda, Mohan (2013-02-05). No mesh inguinal hernia repair-By courtesy from www.hernientage.de.

- Desarda, Mohan P (2008-07-01). "No-mesh inguinal hernia repair with continuous absorbable sutures: A dream or reality? (a study of 229 patients)". Saudi Journal of Gastroenterology. 14 (3): 122–127. doi:10.4103/1319-3767.41730. PMC 2702909. PMID 19568520.

- Szopinski, Jacek; Dabrowiecki, Stanislaw; Pierscinski, Stanislaw; Jackowski, Marek; Jaworski, Maciej; Szuflet, Zbigniew (2012-05-01). "Desarda Versus Lichtenstein Technique for Primary Inguinal Hernia Treatment: 3-Year Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial". World Journal of Surgery. 36 (5): 984–992. doi:10.1007/s00268-012-1508-1. ISSN 0364-2313. PMC 3321139. PMID 22392354.

- Gedam, B.S.; Bansod, Prasad Y.; Kale, V.B.; Shah, Yunus; Akhtar, Murtaza (2017). "A comparative study of Desarda's technique with Lichtenstein mesh repair in treatment of inguinal hernia: A prospective cohort study". International Journal of Surgery. 39: 150–155. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.01.083. PMID 28131917.

- Youssef, Tamer; El-Alfy, Khaled; Farid, Mohamed (2015). "Randomized clinical trial of Desarda versus Lichtenstein repair for treatment of primary inguinal hernia". International Journal of Surgery. 20: 28–34. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.05.055. PMID 26074293.

- Emile, S. H.; Elfeki, H. (2017-09-09). "Desarda's technique versus Lichtenstein technique for the treatment of primary inguinal hernia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Hernia. 22 (3): 385–395. doi:10.1007/s10029-017-1666-z. ISSN 1265-4906. PMID 28889330. S2CID 207046399.

- Zulu, Halalisani Goodman; Mewa Kinoo, Suman; Singh, Bhugwan (July 2016). "Comparison of Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair with the tension-free Desarda technique: a clinical audit and review of the literature". Tropical Doctor. 46 (3): 125–129. doi:10.1177/0049475516655070. ISSN 1758-1133. PMID 27317612. S2CID 9865895.

- Abbas, Zaheer; Bhat, Sujeet Kumar; Koul, Monika; Bhat, Rakesh (2015). "Desarda's No Mesh Repair versus Lichtenstein's Open Mesh Repair of Inguinal Hernia: a comparative study". Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences. 4 (77): 13279–13285. doi:10.14260/jemds/2015/1910.

- "Comparison of the effect of Desarda method and artificial patch in inguinal hernia--《Chinese Journal of Hernia and Abdominal Wall Surgery(Electronic Edition)》2013年06期". en.cnki.com.cn. Archived from the original on 2018-03-07. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

- Rodríguez, P. Rl.; Herrera, P. P.; Gonzalez, O. L.; Alonso, J. R. C.; Blanco, H. S. R. (2013-01-01). "A Randomized Trial Comparing Lichtenstein Repair and No Mesh Desarda Repair for Inguinal Hernia: A Study of 1382 Patients". East and Central African Journal of Surgery. 18 (2): 18–25. ISSN 2073-9990.

- Situma, S. M.; Kaggwa, S.; Masiira, N. M.; Mutumba, S. K. (2009-01-01). "Comparison of Desarda versus modified Bassini inguinal hernia repair: A randomized controlled trial". East and Central African Journal of Surgery. 14 (2): 70–76. ISSN 2073-9990.

- "Desarda Technique Versus Lichtenstein Mesh Repair for the Treatment of Inguinal Hernia A Short-Term Randomized Controlled Trial". medicaljournalofcairouniversity.net. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

- "Minimally invasive surgery - Mayo Clinic". Mayo Clinic.

- ^ "Hernia - laparoscopic surgery (review)". National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 2004. Retrieved 2007-03-26.

- ^ Goers, Trudie A.; Klingensmith, Mary E.; Chen, Li Ern; Glasgow, Sean C. (2008). The Washington Manual of Surgery. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-7447-5.

- Neumayer, Leigh; Giobbie-Hurder, Anita; Jonasson, Olga; Fitzgibbons, Robert; Dunlop, Dorothy; Gibbs, James; Reda, Domenic; Henderson, William; Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program 456 Investigators (2004). "Open Mesh versus Laparoscopic Mesh Repair of Inguinal Hernia". New England Journal of Medicine. 350 (18): 1819–27. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa040093. PMID 15107485. S2CID 26956856.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Aiolfi, A.; Cavalli, M.; Micheletto, G.; Bruni, P. G.; Lombardo, F.; Perali, C.; Bonitta, G.; Bona, D. (June 2019). "Robotic inguinal hernia repair: is technology taking over? Systematic review and meta-analysis". Hernia: The Journal of Hernias and Abdominal Wall Surgery. 23 (3): 509–519. doi:10.1007/s10029-019-01965-1. ISSN 1248-9204. PMID 31093778. S2CID 155103179.

- Qabbani, Amjad; Aboumarzouk, Omar M.; ElBakry, Tamer; Al-Ansari, Abdulla; Elakkad, Mohamed S. (November 2021). "Robotic inguinal hernia repair: systematic review and meta-analysis". ANZ Journal of Surgery. 91 (11): 2277–2287. doi:10.1111/ans.16505. ISSN 1445-2197. PMID 33475236. S2CID 231664671.

- Solaini, Leonardo; Cavaliere, Davide; Avanzolini, Andrea; Rocco, Giuseppe; Ercolani, Giorgio (2022). "Robotic versus laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Robotic Surgery. 16 (4): 775–781. doi:10.1007/s11701-021-01312-6. ISSN 1863-2483. PMC 9314304. PMID 34609697.

- Fitzgibbons, Robert J.; Giobbie-Hurder, Anita; Gibbs, James O.; Dunlop, Dorothy D.; Reda, Domenic J.; McCarthy, Martin; Neumayer, Leigh A.; Barkun, Jeffrey S. T.; Hoehn, James L.; Murphy, Joseph T.; Sarosi, George A.; Syme, William C.; Thompson, Jon S.; Wang, Jia; Jonasson, Olga (2006). "Watchful Waiting vs Repair of Inguinal Hernia in Minimally Symptomatic Men". JAMA. 295 (3): 285–292. doi:10.1001/jama.295.3.285. PMID 16418463. Retrieved 2024-09-17.

- "Laparoscopic versus open repair of groin hernia: a randomised comparison". The Lancet. 354 (9174): 185–190. July 1999. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(98)10010-7. ISSN 0140-6736.

- Eklund, A; Montgomery, A; Bergkvist, L; Rudberg, C (2010-02-23). "Chronic pain 5 years after randomized comparison of laparoscopic and Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair". British Journal of Surgery. 97 (4): 600–608. doi:10.1002/bjs.6904. ISSN 0007-1323. PMID 20186889.

- Berndsen, Fritz H.; Petersson, U.; Arvidsson, D.; Leijonmarck, C.-E.; Rudberg, C.; Smedberg, S.; Montgomery, A. (2007-08-01). "Discomfort five years after laparoscopic and Shouldice inguinal hernia repair: a randomised trial with 867 patients. A report from the SMIL study group". Hernia. 11 (4): 307–313. doi:10.1007/s10029-007-0214-7. ISSN 1248-9204. PMID 17440795.

- O'Dwyer, Patrick J.; Norrie, John; Alani, Ahmed; Walker, Andrew; Duffy, Felix; Horgan, Paul (August 2006). "Observation or Operation for Patients With an Asymptomatic Inguinal Hernia: A Randomized Clinical Trial". Annals of Surgery. 244 (2): 167–173. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000217637.69699.ef. ISSN 0003-4932. PMC 1602168. PMID 16858177.

- Stoker, D.L.; Spiegelhalter, D. J.; Singh, R.; Wellwood, J. M. (May 1994). "Laparoscopic versus open inguinal hernia repair: randomised prospective trial". The Lancet. 343 (8908): 1243–1245. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92148-2. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 7910272.

- Liem, Mike S. L.; van der Graaf, Yolanda; van Steensel, Cees J.; Boelhouwer, Roelof U.; Clevers, Geert-Jan; Meijer, Willem S.; Stassen, Laurents P. S.; Vente, Johannes P.; Weidema, Wibo F.; Schrijvers, Augustinus J. P.; van Vroonhoven, Theo J. M. V. (1997-05-29). "Comparison of Conventional Anterior Surgery and Laparoscopic Surgery for Inguinal-Hernia Repair". New England Journal of Medicine. 336 (22): 1541–1547. doi:10.1056/NEJM199705293362201. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 9164809.

- McCormack, Kirsty; Scott, Neil; Go, Peter M. N. Y. H.; Ross, Sue J; Grant, Adrian; Collaboration the EU Hernia Trialists (2003-01-20). Cochrane Colorectal Cancer Group (ed.). "Laparoscopic techniques versus open techniques for inguinal hernia repair". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (1): CD001785. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001785. PMC 8407507. PMID 12535413.

- "Decision support tool: making a decision about inguinal hernia". www.england.nhs.uk. NHS England. 21 November 2023. Retrieved 2024-09-17.

- Mizrahi, Hagar; Parker, Michael C. (March 2012). "Management of asymptomatic inguinal hernia: a systematic review of the evidence". Archives of Surgery. 147 (3): 277–281. doi:10.1001/archsurg.2011.914. ISSN 1538-3644. PMID 22430913.

- "The Canadian Association of General Surgeons (CAGS) has developed a list of 6 things physicians and patients should question in general surgery". Choosing Wisely Canada. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- Miserez, M.; Peeters, E.; Aufenacker, T.; Bouillot, J. L.; Campanelli, G.; Conze, J.; Fortelny, R.; Heikkinen, T.; Jorgensen, L. N. (April 2014). "Update with level 1 studies of the European Hernia Society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients". Hernia. 18 (2): 151–163. doi:10.1007/s10029-014-1236-6. ISSN 1248-9204. PMID 24647885.

- Chung, L.; Norrie, J.; O'Dwyer, P. J. (April 2011). "Long-term follow-up of patients with a painless inguinal hernia from a randomized clinical trial". The British Journal of Surgery. 98 (4): 596–599. doi:10.1002/bjs.7355. ISSN 1365-2168. PMID 21656724. S2CID 24556052.

- Perioperative Quality Improvement report 2023 (PDF). NIAA Health Services Research Centre. 2023. p. 37.

- Aasvang, Eske Kvanner; Møhl, Bo; Bay-Nielsen, Morten; Kehlet, Henrik (June 2006). "Pain related sexual dysfunction after inguinal herniorrhaphy". Pain. 122 (3): 258–263. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2006.01.035. ISSN 1872-6623. PMID 16545910. S2CID 32383060.

- Kehlet, H. (February 2008). "Chronic pain after groin hernia repair". The British Journal of Surgery. 95 (2): 135–136. doi:10.1002/bjs.6111. ISSN 1365-2168. PMID 18196556. S2CID 32613193.

- Callesen, T.; Bech, K.; Kehlet, H. (December 1999). "Prospective study of chronic pain after groin hernia repair". The British Journal of Surgery. 86 (12): 1528–1531. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01320.x. ISSN 0007-1323. PMID 10594500. S2CID 45862680.

- Starling, J. R.; Harms, B. A.; Schroeder, M. E.; Eichman, P. L. (October 1987). "Diagnosis and treatment of genitofemoral and ilioinguinal entrapment neuralgia". Surgery. 102 (4): 581–586. ISSN 0039-6060. PMID 3660235.

- Aasvang, Eske K.; Kehlet, Henrik (February 2009). "The effect of mesh removal and selective neurectomy on persistent postherniotomy pain". Annals of Surgery. 249 (2): 327–334. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818eec49. ISSN 1528-1140. PMID 19212190. S2CID 26342268.

- Zacest, Andrew C.; Magill, Stephen T.; Anderson, Valerie C.; Burchiel, Kim J. (April 2010). "Long-term outcome following ilioinguinal neurectomy for chronic pain". Journal of Neurosurgery. 112 (4): 784–789. doi:10.3171/2009.8.JNS09533. ISSN 1933-0693. PMID 19780646. S2CID 207702713.

- ^ Amid, Parviz K.; Chen, David C. (October 2011). "Surgical treatment of chronic groin and testicular pain after laparoscopic and open preperitoneal inguinal hernia repair". Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 213 (4): 531–536. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.06.424. ISSN 1879-1190. PMID 21784668.

- Alfieri, S.; Amid, P. K.; Campanelli, G.; Izard, G.; Kehlet, H.; Wijsmuller, A. R.; Di Miceli, D.; Doglietto, G. B. (June 2011). "International guidelines for prevention and management of post-operative chronic pain following inguinal hernia surgery". Hernia. 15 (3): 239–249. doi:10.1007/s10029-011-0798-9. ISSN 1248-9204. PMID 21365287.

- Abi-Haidar, Youmna; Sanchez, Vivian; Itani, Kamal M. F. (September 2011). "Risk factors and outcomes of acute versus elective groin hernia surgery". Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 213 (3): 363–369. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.05.008. ISSN 1879-1190. PMID 21680204.

- Arenal, Juan J.; Rodríguez-Vielba, Paloma; Gallo, Emiliano; Tinoco, Claudia (2002). "Hernias of the abdominal wall in patients over the age of 70 years". The European Journal of Surgery = Acta Chirurgica. 168 (8–9): 460–463. doi:10.1080/110241502321116451. ISSN 1102-4151. PMID 12549685.

- Koch, A.; Edwards, A.; Haapaniemi, S.; Nordin, P.; Kald, A. (December 2005). "Prospective evaluation of 6895 groin hernia repairs in women". The British Journal of Surgery. 92 (12): 1553–1558. doi:10.1002/bjs.5156. ISSN 0007-1323. PMID 16187268. S2CID 43329571.

- Dahlstrand, Ursula; Wollert, Staffan; Nordin, Pär; Sandblom, Gabriel; Gunnarsson, Ulf (April 2009). "Emergency femoral hernia repair: a study based on a national register". Annals of Surgery. 249 (4): 672–676. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e31819ed943. ISSN 1528-1140. PMID 19300219. S2CID 21758273.

- Hewitt, D. Brock; Chojnacki, Karen (2017-10-03). "Laparoscopic Groin Hernia Repair". JAMA. 318 (13): 1294. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.11620. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 28973249.

- Orelio, Claudia C.; van Hessen, Coen; Sanchez-Manuel, Francisco Javier; Aufenacker, Theodorus J.; Scholten, Rob Jpm (21 April 2020). "Antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of postoperative wound infection in adults undergoing open elective inguinal or femoral hernia repair". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4 (10): CD003769. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003769.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7173733. PMID 32315460.

- DynaMed Plus . Ipswich (MA): EBSCO Information Services. 1995 - . Record No. 113880, Groin hernia in adults and adolescents; ; . Available from http://www.dynamed.com/login.aspx?direct=true&site=DynaMed&id=113880 Archived 2021-06-21 at the Wayback Machine. Registration and login required.