In physics and geometry, a catenary (US: /ˈkætənɛri/ KAT-ən-err-ee, UK: /kəˈtiːnəri/ kə-TEE-nər-ee) is the curve that an idealized hanging chain or cable assumes under its own weight when supported only at its ends in a uniform gravitational field.

The catenary curve has a U-like shape, superficially similar in appearance to a parabola, which it is not.

The curve appears in the design of certain types of arches and as a cross section of the catenoid—the shape assumed by a soap film bounded by two parallel circular rings.

The catenary is also called the alysoid, chainette, or, particularly in the materials sciences, an example of a funicular. Rope statics describes catenaries in a classic statics problem involving a hanging rope.

Mathematically, the catenary curve is the graph of the hyperbolic cosine function. The surface of revolution of the catenary curve, the catenoid, is a minimal surface, specifically a minimal surface of revolution. A hanging chain will assume a shape of least potential energy which is a catenary. Galileo Galilei in 1638 discussed the catenary in the book Two New Sciences recognizing that it was different from a parabola. The mathematical properties of the catenary curve were studied by Robert Hooke in the 1670s, and its equation was derived by Leibniz, Huygens and Johann Bernoulli in 1691.

Catenaries and related curves are used in architecture and engineering (e.g., in the design of bridges and arches so that forces do not result in bending moments). In the offshore oil and gas industry, "catenary" refers to a steel catenary riser, a pipeline suspended between a production platform and the seabed that adopts an approximate catenary shape. In the rail industry it refers to the overhead wiring that transfers power to trains. (This often supports a contact wire, in which case it does not follow a true catenary curve.)

In optics and electromagnetics, the hyperbolic cosine and sine functions are basic solutions to Maxwell's equations. The symmetric modes consisting of two evanescent waves would form a catenary shape.

History

The word "catenary" is derived from the Latin word catēna, which means "chain". The English word "catenary" is usually attributed to Thomas Jefferson, who wrote in a letter to Thomas Paine on the construction of an arch for a bridge:

I have lately received from Italy a treatise on the equilibrium of arches, by the Abbé Mascheroni. It appears to be a very scientifical work. I have not yet had time to engage in it; but I find that the conclusions of his demonstrations are, that every part of the catenary is in perfect equilibrium.

It is often said that Galileo thought the curve of a hanging chain was parabolic. However, in his Two New Sciences (1638), Galileo wrote that a hanging cord is only an approximate parabola, correctly observing that this approximation improves in accuracy as the curvature gets smaller and is almost exact when the elevation is less than 45°. The fact that the curve followed by a chain is not a parabola was proven by Joachim Jungius (1587–1657); this result was published posthumously in 1669.

The application of the catenary to the construction of arches is attributed to Robert Hooke, whose "true mathematical and mechanical form" in the context of the rebuilding of St Paul's Cathedral alluded to a catenary. Some much older arches approximate catenaries, an example of which is the Arch of Taq-i Kisra in Ctesiphon.

In 1671, Hooke announced to the Royal Society that he had solved the problem of the optimal shape of an arch, and in 1675 published an encrypted solution as a Latin anagram in an appendix to his Description of Helioscopes, where he wrote that he had found "a true mathematical and mechanical form of all manner of Arches for Building." He did not publish the solution to this anagram in his lifetime, but in 1705 his executor provided it as ut pendet continuum flexile, sic stabit contiguum rigidum inversum, meaning "As hangs a flexible cable so, inverted, stand the touching pieces of an arch."

In 1691, Gottfried Leibniz, Christiaan Huygens, and Johann Bernoulli derived the equation in response to a challenge by Jakob Bernoulli; their solutions were published in the Acta Eruditorum for June 1691. David Gregory wrote a treatise on the catenary in 1697 in which he provided an incorrect derivation of the correct differential equation.

Leonhard Euler proved in 1744 that the catenary is the curve which, when rotated about the x-axis, gives the surface of minimum surface area (the catenoid) for the given bounding circles. Nicolas Fuss gave equations describing the equilibrium of a chain under any force in 1796.

Inverted catenary arch

Catenary arches are often used in the construction of kilns. To create the desired curve, the shape of a hanging chain of the desired dimensions is transferred to a form which is then used as a guide for the placement of bricks or other building material.

The Gateway Arch in St. Louis, Missouri, United States is sometimes said to be an (inverted) catenary, but this is incorrect. It is close to a more general curve called a flattened catenary, with equation y = A cosh(Bx), which is a catenary if AB = 1. While a catenary is the ideal shape for a freestanding arch of constant thickness, the Gateway Arch is narrower near the top. According to the U.S. National Historic Landmark nomination for the arch, it is a "weighted catenary" instead. Its shape corresponds to the shape that a weighted chain, having lighter links in the middle, would form.

-

Catenary arches under the roof of Gaudí's Casa Milà, Barcelona, Spain.

Catenary arches under the roof of Gaudí's Casa Milà, Barcelona, Spain.

-

The Sheffield Winter Garden is enclosed by a series of catenary arches.

The Sheffield Winter Garden is enclosed by a series of catenary arches.

-

The Gateway Arch (St. Louis, Missouri) is a flattened catenary.

The Gateway Arch (St. Louis, Missouri) is a flattened catenary.

-

Catenary arch kiln under construction over temporary form

Catenary bridges

In free-hanging chains, the force exerted is uniform with respect to length of the chain, and so the chain follows the catenary curve. The same is true of a simple suspension bridge or "catenary bridge," where the roadway follows the cable.

A stressed ribbon bridge is a more sophisticated structure with the same catenary shape.

However, in a suspension bridge with a suspended roadway, the chains or cables support the weight of the bridge, and so do not hang freely. In most cases the roadway is flat, so when the weight of the cable is negligible compared with the weight being supported, the force exerted is uniform with respect to horizontal distance, and the result is a parabola, as discussed below (although the term "catenary" is often still used, in an informal sense). If the cable is heavy then the resulting curve is between a catenary and a parabola.

Anchoring of marine objects

The catenary produced by gravity provides an advantage to heavy anchor rodes. An anchor rode (or anchor line) usually consists of chain or cable or both. Anchor rodes are used by ships, oil rigs, docks, floating wind turbines, and other marine equipment which must be anchored to the seabed.

When the rope is slack, the catenary curve presents a lower angle of pull on the anchor or mooring device than would be the case if it were nearly straight. This enhances the performance of the anchor and raises the level of force it will resist before dragging. To maintain the catenary shape in the presence of wind, a heavy chain is needed, so that only larger ships in deeper water can rely on this effect. Smaller boats also rely on catenary to maintain maximum holding power.

Cable ferries and chain boats present a special case of marine vehicles moving although moored by the two catenaries each of one or more cables (wire ropes or chains) passing through the vehicle and moved along by motorized sheaves. The catenaries can be evaluated graphically.

Mathematical description

Equation

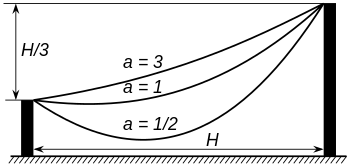

The equation of a catenary in Cartesian coordinates has the form

where cosh is the hyperbolic cosine function, and where a is the distance of the lowest point above the x axis. All catenary curves are similar to each other, since changing the parameter a is equivalent to a uniform scaling of the curve.

The Whewell equation for the catenary is where is the tangential angle and s the arc length.

Differentiating gives and eliminating gives the Cesàro equation where is the curvature.

The radius of curvature is then which is the length of the normal between the curve and the x-axis.

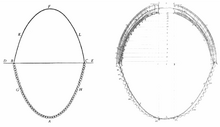

Relation to other curves

When a parabola is rolled along a straight line, the roulette curve traced by its focus is a catenary. The envelope of the directrix of the parabola is also a catenary. The involute from the vertex, that is the roulette traced by a point starting at the vertex when a line is rolled on a catenary, is the tractrix.

Another roulette, formed by rolling a line on a catenary, is another line. This implies that square wheels can roll perfectly smoothly on a road made of a series of bumps in the shape of an inverted catenary curve. The wheels can be any regular polygon except a triangle, but the catenary must have parameters corresponding to the shape and dimensions of the wheels.

Geometrical properties

Over any horizontal interval, the ratio of the area under the catenary to its length equals a, independent of the interval selected. The catenary is the only plane curve other than a horizontal line with this property. Also, the geometric centroid of the area under a stretch of catenary is the midpoint of the perpendicular segment connecting the centroid of the curve itself and the x-axis.

Science

A moving charge in a uniform electric field travels along a catenary (which tends to a parabola if the charge velocity is much less than the speed of light c).

The surface of revolution with fixed radii at either end that has minimum surface area is a catenary

revolved about the x-axis.

Analysis

Model of chains and arches

In the mathematical model the chain (or cord, cable, rope, string, etc.) is idealized by assuming that it is so thin that it can be regarded as a curve and that it is so flexible any force of tension exerted by the chain is parallel to the chain. The analysis of the curve for an optimal arch is similar except that the forces of tension become forces of compression and everything is inverted. An underlying principle is that the chain may be considered a rigid body once it has attained equilibrium. Equations which define the shape of the curve and the tension of the chain at each point may be derived by a careful inspection of the various forces acting on a segment using the fact that these forces must be in balance if the chain is in static equilibrium.

Let the path followed by the chain be given parametrically by r = (x, y) = (x(s), y(s)) where s represents arc length and r is the position vector. This is the natural parameterization and has the property that

where u is a unit tangent vector.

A differential equation for the curve may be derived as follows. Let c be the lowest point on the chain, called the vertex of the catenary. The slope dy/dx of the curve is zero at c since it is a minimum point. Assume r is to the right of c since the other case is implied by symmetry. The forces acting on the section of the chain from c to r are the tension of the chain at c, the tension of the chain at r, and the weight of the chain. The tension at c is tangent to the curve at c and is therefore horizontal without any vertical component and it pulls the section to the left so it may be written (−T0, 0) where T0 is the magnitude of the force. The tension at r is parallel to the curve at r and pulls the section to the right. The tension at r can be split into two components so it may be written Tu = (T cos φ, T sin φ), where T is the magnitude of the force and φ is the angle between the curve at r and the x-axis (see tangential angle). Finally, the weight of the chain is represented by (0, −ws) where w is the weight per unit length and s is the length of the segment of chain between c and r.

The chain is in equilibrium so the sum of three forces is 0, therefore

and

and dividing these gives

It is convenient to write

which is the length of chain whose weight is equal in magnitude to the tension at c. Then

is an equation defining the curve.

The horizontal component of the tension, T cos φ = T0 is constant and the vertical component of the tension, T sin φ = ws is proportional to the length of chain between r and the vertex.

Derivation of equations for the curve

The differential equation , given above, can be solved to produce equations for the curve. We will solve the equation using the boundary condition that the vertex is positioned at and .

First, invoke the formula for arc length to get then separate variables to obtain

A reasonably straightforward approach to integrate this is to use hyperbolic substitution, which gives (where is a constant of integration), and hence

But , so which integrates as (with being the constant of integration satisfying the boundary condition).

Since the primary interest here is simply the shape of the curve, the placement of the coordinate axes are arbitrary; so make the convenient choice of to simplify the result to

For completeness, the relation can be derived by solving each of the and relations for , giving: so which can be rewritten as

Alternative derivation

The differential equation can be solved using a different approach. From

it follows that

and

Integrating gives,

and

As before, the x and y-axes can be shifted so α and β can be taken to be 0. Then

and taking the reciprocal of both sides

Adding and subtracting the last two equations then gives the solution and

Determining parameters

In general the parameter a is the position of the axis. The equation can be determined in this case as follows:

Relabel if necessary so that P1 is to the left of P2 and let H be the horizontal and v be the vertical distance from P1 to P2. Translate the axes so that the vertex of the catenary lies on the y-axis and its height a is adjusted so the catenary satisfies the standard equation of the curve

and let the coordinates of P1 and P2 be (x1, y1) and (x2, y2) respectively. The curve passes through these points, so the difference of height is

and the length of the curve from P1 to P2 is

When L − v is expanded using these expressions the result is

so

This is a transcendental equation in a and must be solved numerically. Since is strictly monotonic on , there is at most one solution with a > 0 and so there is at most one position of equilibrium.

However, if both ends of the curve (P1 and P2) are at the same level (y1 = y2), it can be shown that where L is the total length of the curve between P1 and P2 and h is the sag (vertical distance between P1, P2 and the vertex of the curve).

It can also be shown that and where H is the horizontal distance between P1 and P2 which are located at the same level (H = x2 − x1).

The horizontal traction force at P1 and P2 is T0 = wa, where w is the weight per unit length of the chain or cable.

Tension relations

There is a simple relationship between the tension in the cable at a point and its x- and/or y- coordinate. Begin by combining the squares of the vector components of the tension: which (recalling that ) can be rewritten as But, as shown above, (assuming that ), so we get the simple relations

Variational formulation

Consider a chain of length suspended from two points of equal height and at distance . The curve has to minimize its potential energy (where w is the weight per unit length) and is subject to the constraint

The modified Lagrangian is therefore where is the Lagrange multiplier to be determined. As the independent variable does not appear in the Lagrangian, we can use the Beltrami identity where is an integration constant, in order to obtain a first integral

This is an ordinary first order differential equation that can be solved by the method of separation of variables. Its solution is the usual hyperbolic cosine where the parameters are obtained from the constraints.

Generalizations with vertical force

Nonuniform chains

If the density of the chain is variable then the analysis above can be adapted to produce equations for the curve given the density, or given the curve to find the density.

Let w denote the weight per unit length of the chain, then the weight of the chain has magnitude

where the limits of integration are c and r. Balancing forces as in the uniform chain produces

and and therefore

Differentiation then gives

In terms of φ and the radius of curvature ρ this becomes

Suspension bridge curve

A similar analysis can be done to find the curve followed by the cable supporting a suspension bridge with a horizontal roadway. If the weight of the roadway per unit length is w and the weight of the cable and the wire supporting the bridge is negligible in comparison, then the weight on the cable (see the figure in Catenary#Model of chains and arches) from c to r is wx where x is the horizontal distance between c and r. Proceeding as before gives the differential equation

This is solved by simple integration to get

and so the cable follows a parabola. If the weight of the cable and supporting wires is not negligible then the analysis is more complex.

Catenary of equal strength

In a catenary of equal strength, the cable is strengthened according to the magnitude of the tension at each point, so its resistance to breaking is constant along its length. Assuming that the strength of the cable is proportional to its density per unit length, the weight, w, per unit length of the chain can be written T/c, where c is constant, and the analysis for nonuniform chains can be applied.

In this case the equations for tension are

Combining gives

and by differentiation

where ρ is the radius of curvature.

The solution to this is

In this case, the curve has vertical asymptotes and this limits the span to πc. Other relations are

The curve was studied 1826 by Davies Gilbert and, apparently independently, by Gaspard-Gustave Coriolis in 1836.

Recently, it was shown that this type of catenary could act as a building block of electromagnetic metasurface and was known as "catenary of equal phase gradient".

Elastic catenary

In an elastic catenary, the chain is replaced by a spring which can stretch in response to tension. The spring is assumed to stretch in accordance with Hooke's Law. Specifically, if p is the natural length of a section of spring, then the length of the spring with tension T applied has length

where E is a constant equal to kp, where k is the stiffness of the spring. In the catenary the value of T is variable, but ratio remains valid at a local level, so The curve followed by an elastic spring can now be derived following a similar method as for the inelastic spring.

The equations for tension of the spring are

and

from which

where p is the natural length of the segment from c to r and w0 is the weight per unit length of the spring with no tension. Write so

Then from which

Integrating gives the parametric equations

Again, the x and y-axes can be shifted so α and β can be taken to be 0. So

are parametric equations for the curve. At the rigid limit where E is large, the shape of the curve reduces to that of a non-elastic chain.

Other generalizations

Chain under a general force

With no assumptions being made regarding the force G acting on the chain, the following analysis can be made.

First, let T = T(s) be the force of tension as a function of s. The chain is flexible so it can only exert a force parallel to itself. Since tension is defined as the force that the chain exerts on itself, T must be parallel to the chain. In other words,

where T is the magnitude of T and u is the unit tangent vector.

Second, let G = G(s) be the external force per unit length acting on a small segment of a chain as a function of s. The forces acting on the segment of the chain between s and s + Δs are the force of tension T(s + Δs) at one end of the segment, the nearly opposite force −T(s) at the other end, and the external force acting on the segment which is approximately GΔs. These forces must balance so

Divide by Δs and take the limit as Δs → 0 to obtain

These equations can be used as the starting point in the analysis of a flexible chain acting under any external force. In the case of the standard catenary, G = (0, −w) where the chain has weight w per unit length.

See also

- Catenary arch

- Chain fountain or self-siphoning beads

- Overhead catenary – power lines suspended over rail or tram vehicles

- Roulette (curve) – an elliptic/hyperbolic catenary

- Troposkein – the shape of a spun rope

- Weighted catenary

Notes

- ^ MathWorld

- e.g.: Shodek, Daniel L. (2004). Structures (5th ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-13-048879-4. OCLC 148137330.

- "Shape of a hanging rope" (PDF). Department of Mechanical & Aerospace Engineering - University of Florida. 2017-05-02. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-09-20. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- "The Calculus of Variations". 2015. Retrieved 2019-05-03.

- Luo, Xiangang (2019). Catenary optics. Singapore: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-4818-1. ISBN 978-981-13-4818-1. S2CID 199492908.

- Bourke, Levi; Blaikie, Richard J. (2017-12-01). "Herpin effective media resonant underlayers and resonant overlayer designs for ultra-high NA interference lithography". JOSA A. 34 (12): 2243–2249. Bibcode:2017JOSAA..34.2243B. doi:10.1364/JOSAA.34.002243. ISSN 1520-8532. PMID 29240100.

- Pu, Mingbo; Guo, Yinghui; Li, Xiong; Ma, Xiaoliang; Luo, Xiangang (2018-07-05). "Revisitation of Extraordinary Young's Interference: from Catenary Optical Fields to Spin–Orbit Interaction in Metasurfaces". ACS Photonics. 5 (8): 3198–3204. doi:10.1021/acsphotonics.8b00437. ISSN 2330-4022. S2CID 126267453.

- Pu, Mingbo; Ma, XiaoLiang; Guo, Yinghui; Li, Xiong; Luo, Xiangang (2018-07-23). "Theory of microscopic meta-surface waves based on catenary optical fields and dispersion". Optics Express. 26 (15): 19555–19562. Bibcode:2018OExpr..2619555P. doi:10.1364/OE.26.019555. ISSN 1094-4087. PMID 30114126.

- ""Catenary" at Math Words". Pballew.net. 1995-11-21. Archived from the original on September 6, 2012. Retrieved 2010-11-17.

- Barrow, John D. (2010). 100 Essential Things You Didn't Know You Didn't Know: Math Explains Your World. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-393-33867-6.

- Jefferson, Thomas (1829). Memoirs, Correspondence and Private Papers of Thomas Jefferson. Henry Colbura and Richard Bertley. p. 419.

- ^ Lockwood p. 124

- Fahie, John Joseph (1903). Galileo, His Life and Work. J. Murray. pp. 359–360.

- Jardine, Lisa (2001). "Monuments and Microscopes: Scientific Thinking on a Grand Scale in the Early Royal Society". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 55 (2): 289–308. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2001.0145. JSTOR 532102. S2CID 144311552.

- Denny, Mark (2010). Super Structures: The Science of Bridges, Buildings, Dams, and Other Feats of Engineering. JHU Press. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-0-8018-9437-4.

- cf. the anagram for Hooke's law, which appeared in the next paragraph.

- "Arch Design". Lindahall.org. 2002-10-28. Archived from the original on 2010-11-13. Retrieved 2010-11-17.

- The original anagram was abcccddeeeeefggiiiiiiiillmmmmnnnnnooprrsssttttttuuuuuuuux: the letters of the Latin phrase, alphabetized.

- Truesdell, C. (1960), The Rotational Mechanics of Flexible Or Elastic Bodies 1638–1788: Introduction to Leonhardi Euleri Opera Omnia Vol. X et XI Seriei Secundae, Zürich: Orell Füssli, p. 66, ISBN 9783764314415

- ^ Calladine, C. R. (2015-04-13), "An amateur's contribution to the design of Telford's Menai Suspension Bridge: a commentary on Gilbert (1826) 'On the mathematical theory of suspension bridges'", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 373 (2039): 20140346, Bibcode:2015RSPTA.37340346C, doi:10.1098/rsta.2014.0346, PMC 4360092, PMID 25750153

- Gregorii, Davidis (August 1697), "Catenaria", Philosophical Transactions, 19 (231): 637–652, doi:10.1098/rstl.1695.0114

- Routh Art. 455, footnote

- Minogue, Coll; Sanderson, Robert (2000). Wood-fired Ceramics: Contemporary Practices. University of Pennsylvania. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-8122-3514-2.

- Peterson, Susan; Peterson, Jan (2003). The Craft and Art of Clay: A Complete Potter's Handbook. Laurence King. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-85669-354-7.

- Osserman, Robert (2010), "Mathematics of the Gateway Arch", Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 57 (2): 220–229, ISSN 0002-9920

- Hicks, Clifford B. (December 1963). "The Incredible Gateway Arch: America's Mightiest National Monument". Popular Mechanics. 120 (6): 89. ISSN 0032-4558.

- Harrison, Laura Soullière (1985), National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Gateway Arch / Gateway Arch; or "The Arch", National Park Service and Accompanying one photo, aerial, from 1975 (578 KB)

- Sennott, Stephen (2004). Encyclopedia of Twentieth Century Architecture. Taylor & Francis. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-57958-433-7.

- Hymers, Paul (2005). Planning and Building a Conservatory. New Holland. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-84330-910-9.

- Byer, Owen; Lazebnik, Felix; Smeltzer, Deirdre L. (2010-09-02). Methods for Euclidean Geometry. MAA. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-88385-763-2.

- Fernández Troyano, Leonardo (2003). Bridge Engineering: A Global Perspective. Thomas Telford. p. 514. ISBN 978-0-7277-3215-6.

- Trinks, W.; Mawhinney, M. H.; Shannon, R. A.; Reed, R. J.; Garvey, J. R. (2003-12-05). Industrial Furnaces. Wiley. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-471-38706-0.

- Scott, John S. (1992-10-31). Dictionary Of Civil Engineering. Springer. p. 433. ISBN 978-0-412-98421-1.

- Finch, Paul (19 March 1998). "Cranked stress ribbon design to span Medway". Architects' Journal. 207: 51.

- ^ Lockwood p. 122

- Kunkel, Paul (June 30, 2006). "Hanging With Galileo". Whistler Alley Mathematics. Retrieved March 27, 2009.

- "Chain, Rope, and Catenary – Anchor Systems For Small Boats". Petersmith.net.nz. Retrieved 2010-11-17.

- "Efficiency of Cable Ferries - Part 2". Human Power eJournal. Retrieved 2023-12-08.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Catenary". MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. Retrieved 2019-09-21.

The parametric equations for the catenary are given by x(t) = t, y(t) = a cosh(t/a), where t=0 corresponds to the vertex

- MathWorld, eq. 7

- Routh Art. 444

- ^ Yates, Robert C. (1952). Curves and their Properties. NCTM. p. 13.

- Yates p. 80

- Hall, Leon; Wagon, Stan (1992). "Roads and Wheels". Mathematics Magazine. 65 (5): 283–301. doi:10.2307/2691240. JSTOR 2691240.

- Parker, Edward (2010). "A Property Characterizing the Catenary". Mathematics Magazine. 83: 63–64. doi:10.4169/002557010X485120. S2CID 122116662.

- Landau, Lev Davidovich (1975). The Classical Theory of Fields. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-7506-2768-9.

- Routh Art. 442, p. 316

- Church, Irving Porter (1890). Mechanics of Engineering. Wiley. p. 387.

- Whewell p. 65

- Following Routh Art. 443 p. 316

- Routh Art. 443 p. 317

- Whewell p. 67

- Routh Art 443, p. 318

- A minor variation of the derivation presented here can be found on page 107 of Maurer. A different (though ultimately mathematically equivalent) derivation, which does not make use of hyperbolic function notation, can be found in Routh (Article 443, starting in particular at page 317).

- Following Lamb p. 342

- Following Todhunter Art. 186

- See Routh art. 447

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Chaînette - partie 3 : longueur". YouTube.

- Routh Art 443, p. 318

- Following Routh Art. 450

- Following Routh Art. 452

- Ira Freeman investigated the case where only the cable and roadway are significant, see the External links section. Routh gives the case where only the supporting wires have significant weight as an exercise.

- Following Routh Art. 453

- Pu, Mingbo; Li, Xiong; Ma, Xiaoliang; Luo, Xiangang (2015). "Catenary Optics for Achromatic Generation of Perfect Optical Angular Momentum". Science Advances. 1 (9): e1500396. Bibcode:2015SciA....1E0396P. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1500396. PMC 4646797. PMID 26601283.

- Routh Art. 489

- Routh Art. 494

- Following Routh Art. 500

- Follows Routh Art. 455

Bibliography

- Lockwood, E.H. (1961). "Chapter 13: The Tractrix and Catenary". A Book of Curves. Cambridge.

- Salmon, George (1879). Higher Plane Curves. Hodges, Foster and Figgis. pp. 287–289.

- Routh, Edward John (1891). "Chapter X: On Strings". A Treatise on Analytical Statics. University Press.

- Maurer, Edward Rose (1914). "Art. 26 Catenary Cable". Technical Mechanics. J. Wiley & Sons.

- Lamb, Sir Horace (1897). "Art. 134 Transcendental Curves; Catenary, Tractrix". An Elementary Course of Infinitesimal Calculus. University Press.

- Todhunter, Isaac (1858). "XI Flexible Strings. Inextensible, XII Flexible Strings. Extensible". A Treatise on Analytical Statics. Macmillan.

- Whewell, William (1833). "Chapter V: The Equilibrium of a Flexible Body". Analytical Statics. J. & J.J. Deighton. p. 65.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Catenary". MathWorld.

Further reading

- Swetz, Frank (1995). Learn from the Masters. MAA. pp. 128–9. ISBN 978-0-88385-703-8.

- Venturoli, Giuseppe (1822). "Chapter XXIII: On the Catenary". Elements of the Theory of Mechanics. Trans. Daniel Cresswell. J. Nicholson & Son.

External links

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Catenary", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Catenary at PlanetMath.

- Catenary curve calculator

- Catenary at The Geometry Center

- "Catenary" at Visual Dictionary of Special Plane Curves

- The Catenary - Chains, Arches, and Soap Films.

- Cable Sag Error Calculator – Calculates the deviation from a straight line of a catenary curve and provides derivation of the calculator and references.

- Dynamic as well as static cetenary curve equations derived – The equations governing the shape (static case) as well as dynamics (dynamic case) of a centenary is derived. Solution to the equations discussed.

- The straight line, the catenary, the brachistochrone, the circle, and Fermat Unified approach to some geodesics.

- Ira Freeman "A General Form of the Suspension Bridge Catenary" Bulletin of the AMS

and

and

where cosh is the

where cosh is the  where

where  is the

is the  and eliminating

and eliminating  where

where  is the

is the  which is the length of the

which is the length of the

and

and

, given above, can be solved

to produce equations for the curve.

We will solve the equation using the boundary condition that

the vertex is positioned at

, given above, can be solved

to produce equations for the curve.

We will solve the equation using the boundary condition that

the vertex is positioned at  and

and  .

.

then

then

(where

(where  is a

is a

, so

, so

which

which  (with

(with  being the constant of integration satisfying the boundary condition).

being the constant of integration satisfying the boundary condition).

to simplify the result to

to simplify the result to

relation can be derived by

solving each of the

relation can be derived by

solving each of the  and

and  relations for

relations for  , giving:

, giving:

so

so

which

which

and

and

and

and

and taking the reciprocal of both sides

and taking the reciprocal of both sides

and

and

so

so

is strictly monotonic on

is strictly monotonic on  , there is at most one solution with a > 0 and so there is at most one position of equilibrium.

, there is at most one solution with a > 0 and so there is at most one position of equilibrium.

where L is the total length of the curve between P1 and P2 and h is the sag (vertical distance between P1, P2 and the vertex of the curve).

where L is the total length of the curve between P1 and P2 and h is the sag (vertical distance between P1, P2 and the vertex of the curve).

and

and

where H is the horizontal distance between P1 and P2 which are located at the same level (H = x2 − x1).

where H is the horizontal distance between P1 and P2 which are located at the same level (H = x2 − x1).

which (recalling that

which (recalling that  ) can be rewritten as

) can be rewritten as

But,

But,  (assuming that

(assuming that  ), so we get the simple relations

), so we get the simple relations

suspended from two points of equal height and at distance

suspended from two points of equal height and at distance  . The curve has to minimize its potential energy

. The curve has to minimize its potential energy

(where w is the weight per unit length) and is subject to the constraint

(where w is the weight per unit length) and is subject to the constraint

where

where  is the

is the  does not appear in the Lagrangian, we can use the

does not appear in the Lagrangian, we can use the  where

where  is an integration constant, in order to obtain a first integral

is an integration constant, in order to obtain a first integral

and therefore

and therefore

The curve followed by an elastic spring can now be derived following a similar method as for the inelastic spring.

The curve followed by an elastic spring can now be derived following a similar method as for the inelastic spring.

and

and

so

so

from which

from which