The iodine pit, also called the iodine hole or xenon pit, is a temporary disabling of a nuclear reactor due to buildup of short-lived nuclear poisons in the reactor core. The main isotope responsible is Xe, mainly produced by natural decay of I. I is a weak neutron absorber, while Xe is the strongest known neutron absorber. When Xe builds up in the fuel rods of a reactor, it significantly lowers their reactivity, by absorbing a significant amount of the neutrons that provide the nuclear reaction.

The presence of I and Xe in the reactor is one of the main reasons for its power fluctuations in reaction to change of control rod positions.

The buildup of short-lived fission products acting as nuclear poisons is called reactor poisoning, or xenon poisoning. Buildup of stable or long-lived neutron poisons is called reactor slagging.

Fission products decay and burnup

One of the common fission products is Te, which undergoes beta decay with half-life of 19 seconds to I. I itself is a weak neutron absorber. It builds up in the reactor in the rate proportional to the rate of fission, which is proportional to the reactor thermal power. I undergoes beta decay with half-life of 6.57 hours to Xe. The yield of Xe for uranium fission is 6.3%; about 95% of Xe originates from decay of I.

Xe is the most powerful known neutron absorber, with a cross section for thermal neutrons of 2.6×10 barns, so it acts as a "poison" that can slow or stop the chain reaction after a period of operation. This was discovered in the earliest nuclear reactors built by the Manhattan Project for plutonium production. As a result, the designers made provisions in the design to increase the reactor's reactivity (the number of neutrons per fission that go on to fission other atoms of nuclear fuel). Xe reactor poisoning played a major role in the Chernobyl disaster.

By neutron capture, Xe is transformed ("burned") to Xe, which is effectively stable and does not significantly absorb neutrons.

The burn rate is proportional to the neutron flux, which is proportional to the reactor power; a reactor running at twice the power will have twice the xenon burn rate. The production rate is also proportional to reactor power, but due to the half-life time of I, this rate depends on the average power over the past several hours.

As a result, a reactor operating at constant power has a fixed steady-state equilibrium concentration, but when lowering reactor power, the Xe concentration can increase enough to effectively shut down the reactor. Without enough neutrons to offset their absorption by Xe, nor to burn the built-up xenon, the reactor has to be kept in shutdown state for 1–2 days until enough of the Xe decays.

Xe beta-decays with half-life of 9.2 hours to Cs; a poisoned core will spontaneously recover after several half-lives. After about 3 days of shutdown, the core can be assumed to be free of Xe, without it introducing errors into the reactivity calculations.

The inability of the reactor to be restarted in such state is called xenon precluded start up or dropping into an iodine pit; the duration of this situation is known as xenon dead time, poison outage, or iodine pit depth. Due to the risk of such situations, in the early Soviet nuclear industry, many servicing operations were performed on running reactors, as downtimes longer than an hour led to xenon buildup that could keep the reactor offline for significant time, lower the production of Pu, required for nuclear weapons, and would lead to investigations and punishment of the reactor operators.

Xenon-135 oscillations

The interdependence of Xe buildup and the neutron flux can lead to periodic power fluctuations. In large reactors, with little neutron flux coupling between their regions, flux nonuniformities can lead to formation of xenon oscillations, periodic local variations of reactor power moving through the core with a period of about 15 hours. A local variation of neutron flux causes increased burnup of Xe and production of I, depletion of Xe increases the reactivity in the core region. The local power density can change by a factor of three or more, while the average power of the reactor stays more or less unchanged. Strong negative temperature coefficient of reactivity causes damping of these oscillations, and is a desired reactor design feature.

Iodine pit behavior

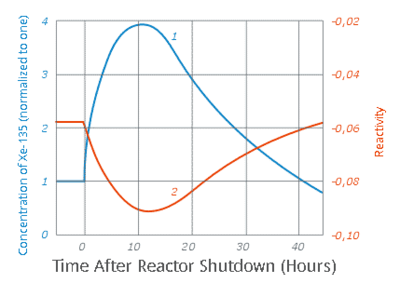

The reactivity of the reactor after the shutdown first decreases, then increases again, having a shape of a pit; this gave the "iodine pit" its name. The degree of poisoning, and the depth of the pit and the corresponding duration of the outage, depends on the neutron flux before the shutdown. Iodine pit behavior is not observed in reactors with neutron flux density below 5×10 neutrons ms, as the Xe is primarily removed by decay instead of neutron capture. As the core reactivity reserve is usually limited to 10% of Dk/k, thermal power reactors tend to use neutron flux at most about 5×10 neutrons ms to avoid restart problems after shutdown.

The concentration changes of Xe in the reactor core after its shutdown is determined by the short-term power history of the reactor (which determines the initial concentrations of I and Xe), and then by the half-life differences of the isotopes governing the rates of its production and removal; if the activity of I is higher than activity of Xe, the concentration of Xe will rise, and vice versa.

During reactor operation at a given power level, a secular equilibrium is established within 40–50 hours, when the production rate of iodine-135, its decay to xenon-135, and its burning to xenon-136 and decay to caesium-135 are keeping the xenon-135 amount in the reactor constant at a given power level.

The equilibrium concentration of I is proportional to the neutron flux φ. The equilibrium concentration of Xe, however, depends very little on neutron flux for φ > 10 neutrons ms.

Increase of the reactor power, and the increase of neutron flux, causes a rise in production of I and consumption of Xe. At first, the concentration of xenon decreases, then slowly increases again to a new equilibrium level as now excess I decays. During typical power increases from 50 to 100%, the Xe concentration falls for about 3 hours.

Decrease of the reactor power lowers production of new I, but also lowers the burn rate of Xe. For a while Xe builds up, governed by the amount of available I, then its concentration decreases again to an equilibrium for the given reactor power level. The peak concentration of Xe occurs after about 11.1 hours after power decrease, and the equilibrium is reached after about 50 hours. A total shutdown of the reactor is an extreme case of power decrease.

Design precautions

If sufficient reactivity control authority is available, the reactor can be restarted, but a xenon burn-out transient must be carefully managed. As the control rods are extracted and criticality is reached, neutron flux increases many orders of magnitude and the Xe begins to absorb neutrons and be transmuted to Xe. The reactor burns off the nuclear poison. As this happens, the reactivity increases and the control rods must be gradually re-inserted or reactor power will increase. The time constant for this burn-off transient depends on the reactor design, power level history of the reactor for the past several days (therefore the Xe and I concentrations present), and the new power setting. For a typical step up from 50% power to 100% power, Xe concentration falls for about 3 hours.

The first time Xe poisoning of a nuclear reactor occurred was on September 28, 1944, in Pile 100-B at the Hanford Site. The B Reactor was a plutonium production reactor built by DuPont as part of the Manhattan Project. The reactor was started on September 27, 1944, but the power dropped unexpectedly shortly after, leading to a complete shutdown on the evening of September 28. Next morning the reaction restarted by itself. The physicists John Archibald Wheeler, working for DuPont at the time, and Enrico Fermi were able to identify that the drop in the neutron flux and the consequent shutdown was caused by the accumulation of Xe in the reactor fuel. The reactor was built with spare fuel channels that were then used to increase the normal operating levels of the reactor, thus increasing the burn-up rate of the accumulating Xe.

Reactors with large physical dimensions, e.g. the RBMK type, can develop significant nonuniformities of xenon concentration through the core. Control of such non-homogeneously poisoned cores, especially at low power, is a challenging problem. The Chernobyl disaster occurred after recovering Reactor 4 from a nonuniformly poisoned state. Reactor power was significantly reduced in preparation for a test, to be followed by a scheduled shutdown. Just before the test, the power plummeted in part due to the accumulation of Xe as a result of the low burn-up rate at low power. Operators withdrew most of the control rods in an attempt to bring the power back up. Unbeknownst to the operators, these and other actions put the reactor in a state where it was exposed to a feedback loop of neutron power and steam production. A flawed shutdown system then caused a power surge that led to the explosion and destruction of reactor 4.

The iodine pit effect has to be taken in account for reactor designs. High values of power density, leading to high production rates of fission products and therefore higher iodine concentrations, require higher amount and enrichment of the nuclear fuel used to compensate. Without this reactivity reserve, a reactor shutdown would preclude its restart for several tens of hours until I/Xe sufficiently decays, especially shortly before replacement of spent fuel (with high burnup and accumulated nuclear poisons) with fresh one.

Fluid fuel reactors cannot develop xenon inhomogeneity because the fuel is free to mix. Also, the Molten Salt Reactor Experiment demonstrated that spraying the liquid fuel as droplets through a gas space during recirculation can allow xenon and krypton to leave the fuel salts.

Notes

- Xenon-136 undergoes double beta decay with an extremely long half-life of 2.165×10 years.

- Removing Xe from neutron exposure also means that the reactor will produce more of the long-lived fission product Cs. However, thanks to the short 3.8-minute half-life of Xe it will mostly decay in the fuel, leaving the Cs significantly less contaminated with the far more active Cs and so more suitable for treatments like nuclear transmutation.

References

- Stacey, Weston M. (2007). Nuclear Reactor Physics. Wiley-VCH. p. 213. ISBN 978-3-527-40679-1.

- Staff. "Hanford Becomes Operational". The Manhattan Project: An Interactive History. U.S. Department of Energy, Office of History and Heritage Resources. Archived from the original on October 14, 2010. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- Pfeffer, Jeremy I.; Nir, Shlomo (2000). Modern Physics: An Introductory Text. Imperial College Press. pp. 421 ff. ISBN 1-86094-250-4.

- ^ "Xenon-135 Oscillations". Nuclear Physics and Reactor Theory (PDF). Vol. 2 of 2. U.S. Department of Energy. January 1993. p. 39. DOE-HDBK-1019/2-93. Retrieved 2014-08-21.

- Kruglov, Arkadii (15 August 2002). The History of the Soviet Atomic Industry. CRC Press. pp. 57, 60. ISBN 0-41526-970-9.

- ^ Xenon decay transient graph

- DOE Fundamentals Handbook: Nuclear Physics and Reactor Theory Volume 2 (PDF). U.S. Department of Energy. January 1993. pp. 35–42. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-11-09. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- "John Wheeler's Interview (1965)". www.manhattanprojectvoices.org. Retrieved 2019-06-19.

- C.R. Nave. "Xenon Poisoning". HyperPhysics. Georgia State University. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- Петунин В. П. Теплоэнергетика ядерных установок. — М.: Атомиздат, 1960.

- Левин В. Е. Ядерная физика и ядерные реакторы. 4-е изд. — М.: Атомиздат, 1979.