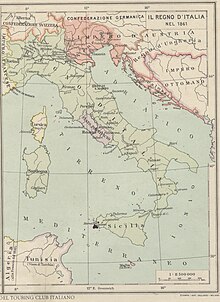

The Italo-Prussian Alliance was a military pact signed by the Kingdom of Italy and the Kingdom of Prussia on 8 April 1866. It established the terms on which the two nations would enter hostilities against Austria and their respective compensations in the event of victory. For Italy, this was to be the Veneto; for Prussia, other territories of Austria. The alliance led to the Austro-Prussian War which on the Italian front took the name of Third Italian War of Independence. At the end of the conflict, thanks to Prussia's victories, Italy obtained the Veneto while Prussia placed itself at the head of the new North German Confederation.

Background

Initiatives by Cavour and La Marmora

After the armistice of Villafranca which concluded the Second Italian War of Independence and confirmed that Veneto would remain Austrian, Italian Prime Minister Cavour realised that his country might be able to secure Austrian withdrawal from the province through an agreement with Prussia. In January 1861, a few months before his death, Cavour sent Alfonso La Marmora to Berlin, officially to represent the Kingdom of Italy at the coronation of Kaiser Wilhelm I. However, the mission also had the secret aim of sounding out the intentions of the Prussian government regarding a possible agreement against Austria. The mission did not have a positive outcome, especially due to the conservatism of Prussia, which was wary of alliance with a nation it considered too liberal in its politics.

Between 1861-1866 Italy made further attempts to obtain Veneto from Austria. As Austria did not recognise the new Kingdom of Italy, the Italian government was obliged to negotiate through the mediation of France or Great Britain. A first step was made by Giuseppe Pasolini in December 1863 and a second by La Marmora in November 1864. Neither attempt, however, yielded useful results. In October 1865, Italian diplomacy took a final step to obtain the Veneto without bloodshed when La Marmora authorized Count Alessandro Malaguzzi Valeri to open secret negotiations with Austria, which was offered a large sum of money in exchange for the region. This mission also failed.

Bismarck's maneuvers

In 1865, Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck decided to end Austrian influence over Germany by defeating it in war. He therefore initiated exploratory contacts with France and Italy. At the end of July 1865 he had one of his diplomats, Karl von Usedom, ask Prime Minister La Marmora what attitude Italy would have in the event of an Austro-Prussian conflict. La Marmora's response was cautious: in order not to alienate an old ally he declared that he could not make commitments without knowing the intentions of Napoleon III of France.

Questioned about this on 13 August 1865 by the Italian ambassador in Paris Costantino Nigra, the French Foreign Minister Drouyn de Lhuys reported that France would remain neutral in the event of an Austro-Prussian war and would not oppose Italy's involvement on Prussia’s side.

In September Bismarck confirmed to the Italian representative in Berlin Quigini Pulica that the final clash with Austria was still intended. However, to avoid the danger of Prussia being attacked in turn by neighbouring powers, he first had to make sure of Russia's neutral attitude and Great Britain's disinterest before consulting France. This led to meetings between Bismarck and Napoleon III in Biarritz and Paris in October and November 1865, during which the French emperor confirmed that he would maintain neutrality.

Returning from France, Bismarck brought about a worsening of Austro-Prussian relations. First he provoked incidents in the former Danish Duchies of Schleswig and Holstein that had been partitioned between Prussia and Austria following the Second Schleswig War. Then, on 26 January 1866, he sent Austria a harsh note of protest accusing it of plotting with the Augustenburgs, pretenders to the throne of the duchies. On 7 February, the Austrian Foreign Minister, Alexander von Mensdorff, in turn protested against Prussian interference in the administration of the Duchy of Holstein and against the unbearable climate created by Prussia. Finally, in Berlin, on 28 February 1866, the Prussian Crown Council decided in favour of war against Austria and forming an alliance with Italy.

Final negotiations

During the same meeting, the Prussian Crown Council decided to ask the Italian government to send an officer to Berlin to deal with the military issues of a possible alliance, while a Prussian one would be sent to Florence. For Italy, the person in charge of the mission was General Giuseppe Govone who arrived in Berlin on 10 March 1866.

The general, who left Florence with "few and generic" instructions, did not get a very encouraging impression from his first conversation with Bismarck. In fact, the Chancellor first proposed a general treaty with Italy which, lacking any military specifics, seemed more suited to intimidating Austria in order to obtain advantages on the question of Schleswig and Holstein than anything else. This was due to the fact that Bismarck’s plans were opposed at the court of Kaiser Wilhelm I, leaving him unable to immediately conclude a reciprocal military treaty with Italy, which was what La Marmora wanted. However, Napoleon III's encouragement to seize the opportunity and conclude a treaty convinced the Italians to put aside their reservations. From Paris, Costantino Nigra wrote to La Marmora on 23 March 1866 that the emperor advised Italy to accept the alliance with Prussia and that he would not allow Austria to attack Italy if Prussia then withdrew from the conflict.

The treaty

After having examined a draft of the treaty from Bismarck, on 28 March 1866, La Marmora telegraphed to his representative in Berlin Giulio De Barral to communicate to him the favourable impression that the proposal had received in Florence. On the 31st, another communication from Nigra to La Marmora conveyed Napoleon III’s desire to start a war in order to find a way to extend the borders of France on the Rhine; as well as the assurance that if Austria were to attack Italy first, France would intervene against Austria.

At this point there was nothing left to do but conclude. Accordingly the Italian-Prussian alliance treaty was signed in Berlin on 8 April 1866 by De Barral and Govone for Italy, and by Bismarck for Prussia. Its text provided that:

- Art. 1. There will be friendship and alliance between His Majesty the King of Italy and His Majesty the King of Prussia.

- Art. 2. If the negotiations that His Majesty the King of Prussia is about to open with other German Governments by virtue of a reform of the Federal Constitution in conformity with the needs of the German Nation do not succeed, and His Majesty is consequently put in a position to take up arms to make his proposals prevail, His Majesty the King of Italy, following the initiative taken by Prussia, as soon as he is informed, by virtue of the present convention, will declare war on Austria.

- Art. 3. From that moment, the war will be continued by Their Royal Highnesses, with all the forces that Providence has placed at their disposal, and neither Italy nor Prussia will be able to conclude peace or armistice without mutual consent.

- Art. 4. Consent cannot be refused when Austria has agreed to cede the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia, and to Prussia, Austrian territories equivalent in population to the said Kingdom.

- Art. 5. This treaty shall cease to have force three months after its signature, if in that interval Prussia has not declared war on Austria.

- Art. 6. If the Austrian fleet leaves the Adriatic Sea before the declaration of war, His Majesty the King of Italy will send a sufficient number of vessels to the Baltic Sea, where they will be stationed ready to join the Prussian navy as soon as hostilities begin.

Both parties agreed to keep the treaty secret. As soon as the treaty was signed, Bismarck presented to the Frankfurt Diet a proposal to establish a new German Confederation from which Austria would be excluded. The was intended to create confusion in Austria (the leader of the confederation), but instead the proposal was received in the Diet with distrust and sarcasm.

Post-treaty developments

Austrian proposal to sell the Veneto

When news of the Italy-Prussian alliance spread, Austria made several attempts to break it. The most significant was the proposal to cede Veneto to France (Austria officially had no relations with Italy) in exchange for French and Italian neutrality in the event of an Austro-Prussian conflict.

The proposal was made by the Austrian government to Napoleon III who informed Nigra on 4 May 1866. The latter, the following day, telegraphed to La Marmora . The offer was conditional on the non-intervention of France and Italy in favour of Prussia and consisted of the following points.

- Cession of the Veneto to France which in turn would cede it to Italy

- Payment of a sum of money by Italy which would be used for the construction of Austrian fortifications on the new border

- All this after the Austrian occupation of the Prussian Province of Silesia.

Initially, the offer seemed interesting to La Marmora, especially since the treaty just concluded with Prussia did not oblige Prussia to help Italy in the event of an attack by Austria. The proposal was not, however, free of drawbacks. First of all, it would have violated a pact with Prussia, which would have become an enemy of Italy. Secondly, Italy would have been indebted to France for the cession of the Veneto. Thirdly, Vienna's offer was linked to the Austrian occupation of Silesia, which appeared to be quite unlikely.

La Marmora wanted to sound out Prussia's likely response in the event of a preventive Austrian attack on Italy, in order to be able to decide on Vienna's offer with greater peace of mind. On 7 May, he received the reply from Ambassador De Barral that both Bismarck and William I, despite the treaty not explicitly providing for it, had given assurances that Prussia would come to Italy's aid in the event of an Austrian attack. Thus reassured, after a fruitful exchange of ideas between Govone and Nigra in Paris (both opposed to accepting the offer), La Marmora decided to refuse the Austrian proposal « the government of Florence being resolved not to compromise on the commitments undertaken with Prussia, beyond the limits within which Prussia would be willing to do, on the commitments undertaken with Italy», as he communicated to Govone who, having arrived in the capital, left again on the evening of the 14th for Paris.

Napoleon III's maneuvers

With the Austrian proposal set aside, the Italian-Prussian alliance had to face another test. Napoleon III, evidently beginning to doubt the advantage to France from a war between Austria and Prussia, proposed to convene a European congress to try and resolve all of the current sources of tension: the Veneto, Schleswig-Holstein and the reform of the German Confederation. The congress was also intended to discuss the establishment of a neutral state on the Rhine for the benefit of France. Austria, offered unspecified compensation for this, was nevertheless convinced that it could recover Silesia in exchange for the Veneto only through war. It thus rejected the proposed congress, thereby making the French proposal unworkable. Napoleon III did however manage to wrest an agreement from Vienna (June 12, 1866) to cede Veneto to him in the event of victory over Prussia. In exchange, France would not intervene against Austria and would induce Italy to do the same.

Outbreak of war

Main articles: Austro-Prussian War and Third Italian War of IndependenceOn 12 June (the day of the agreement with France), Vienna broke off diplomatic relations with Berlin and on the 14th presented a motion to the German Diet for federal mobilization against Prussia. Berlin then declared the German Confederation dissolved and on the 15th advanced its army southwards invading the Kingdom of Saxony which had sided with Austria. On the 16th June fighting actually broke out.

La Marmora transmitted Italy’s declaration of war to Vienna on 20 June 1866, with the start of hostilities set for 23 June. On the 21st, meanwhile, Prussian troops had reached the northern border of Austria. In Florence, La Marmora was appointed chief of staff and replaced in government by Bettino Ricasoli. La Marmora was then sent to the field and on the 24th was defeated by the Austrians at Custoza. On 3 July, however, the Prussians won the battle of Sadowa, putting the main Austrian army out of action.

French mediation and the end of the alliance

The day before the defeat at Sadowa, the Austrians had already set in motion their second attempt to break the Italo-Prussian alliance. Warned of the impending military catastrophe by General Benedek, the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I, during the night between 2 and 3 July 1866, thought of immediately and unconditionally offering the Veneto to Napoleon III in order to obtain an armistice with Italy. After Sadowa, on the 4th, he acted on this thought which was communicated to the Austrian ambassador in Paris on the evening of the same day. Napoleon III, who was beginning to seriously fear the consequences of a dramatic and decisive Prussian success, telegraphed Victor Emmanuel II on 5 July offering him the Veneto in exchange for peace with Austria. At the same time he had the news of the offer published in Le Moniteur Universel to create additional pressure.

The Italian government reacted very coldly to the French Emperor’s initiative, although Paris continued to put pressure on Florence. For Prime Minister Ricasoli, outright refusal of French mediation was impossible but he played for time, continuing military operations with maximum energy for as long as possible. Napoleon also made an offer to Prussia of mediation, which Bismarck, confident that he had achieved the objectives of his war, accepted. This led to an agreement in principle between Austria and Prussia which established the creation of a North German Confederation under Prussian leadership and the exclusion of Austria from all German affairs. Once the plan was accepted by Vienna and Berlin, a truce was reached.

The Italian army had, in the meantime, occupied the Veneto, abandoned by the Austrians, and was now converging on Trento. The truce between the Austrians and the Prussians was decided on 21 July, valid from midday on the 22nd. The government of Florence received news of the agreement only indirectly, through France. Italy, however, was seeking a military victory and to Napoleon III's requests for peace it initially responded that it was waiting for direct official communication from its Prussian ally. Then, however, on 22 July, news arrived of the decisive Austrian defeat of the Italian navy at Lissa and the following day Italy also agreed to a truce.

The armistice began on the morning of 25 July. On that date, Italian troops had occupied part of Trentino and the Italian government was concerned with preserving control over this territory. Bismarck opposed this, claiming that he had accepted the French proposal for the integrity of the Austrian Empire with the sole exception of Veneto. The Italian Foreign Minister Emilio Visconti Venosta then suspended the armistice in the hope that a local victory that would allow him to keep Trentino. However, faced with the signing of the preliminaries of peace between Austria and Prussia on 26 July, on the 29th Italy sent its conditions to France, the mediating power. Austria refused to cede anything other than Veneto and Prussia refused to continue the war alongside Italy. The Italian troops in Trentino commanded by Garibaldi and Medici were then recalled and on 12 August, at Cormons, the final armistice between Italy and Austria was concluded, followed on 3 October by the Peace of Vienna. This established the cession to Italy of only Veneto through France. The third war of independence was over, and with it the Italo-Prussian alliance.

See also

References

- ^ Silva, Pietro (1915). L'Italia e la Guerra di 1866 (PDF). Milan: Ravà & C. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- ^ Biguzzi, Stefano (22 April 2016). "ALLEANZA PRUSSIANA". Brescia Oggi. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- ^ Comandini, Alfredo (1916). "Italy, Prussia, and Austria, 1866-1916". Current History (1916-1940). 5 (3): 531–533. doi:10.1525/curh.1916.5.3.531. JSTOR 45328122. Retrieved 26 December 2024.

- ^ Whittam, John (2024). The Politics of the Italian Army 1861-1918. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781040274460. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- ^ Bortolotti, Sandro (1941). La Guerra del 1866. Milan: Istituto per gli Studi di Politica Internazionale.

- Fruci, Gian Luca. "PASOLINI DALL'ONDA, Giuseppe". treccani.it. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- Pasolini, Pier Desiderio (1881). Giuseppe Pasolini, Memorie (1815 - 1876) raccolte da suo figlio. Tip. Galeati. p. 319. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- ^ Giordano, Giancarlo (2008). Cilindri e feluche: la politica estera dell'Italia dopo l'unità. Aracne. ISBN 978-8854817333.

- "L'Alleanza Italo-Germanica nel Pensiero di Bismarck" (PDF). 150anni.it. 150 anni. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- ^ Wawro, Geoffrey (1996). The Austro-Prussian War Austria's War with Prussia and Italy in 1866. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521629515. Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- Fyffe, Charles Alan (1890). A History of Modern Europe: From 1848 to 1878. H. Holt. p. 365. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- ^ Jacini, Stefano (1868). Due anni di politica italiana (dalla convenzione del 15 settembre alla liberazione del Veneto). Milan: Stabilimento Giuseppe Civelli. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- ^ von Sybel, Heinrich (1942). Deutsche Einheit – Idee und Wirklichkeit von Villafranca bis Königgrätz, vol. 4. Mumich: F. Bruckmann. pp. 340–347.

- Malinverni, Bruno. "BARRAL de Monteauvrard, Giulio Camillo conte di". treccani.it. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- Stürmer, Michael (1984). Die Reichsgründung. Munich: DTV. pp. 140–142. ISBN 3-423-04504-3.

- ^ Nichols Barker, Nancy (2011). Distaff Diplomacy The Empress Eugénie and the Foreign Policy of the Second Empire. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292735927. Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- ^ Chiala, Luigi (1902). Ancora un po' più di luce sugli eventi politici e militari dell'anno 1866. Florence: Berbera.

- ^ Taylor, Alan John Percival (1961). L'Europa delle grandi potenze. Da Metternich a Lenin. Bari: Laterza. pp. 244–7.

- 1866 in Italy

- 1866 in Prussia

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946)

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Prussia

- Otto von Bismarck

- Napoleon III

- Austro-Prussian War

- Third Italian War of Independence

- Bilateral relations of Prussia

- Foreign relations of Austria-Hungary

- History of the foreign relations of France

- 19th-century military alliances

- Military alliances involving Prussia

- Military alliances involving Italy